-

15 August 2025 | Country Update

Slovakia’s €2 billion ambulance tender sparks political and legal turmoil -

15 August 2025 | Policy Analysis

Out-of-pocket payments in Slovakia reach EUR 1.7 billion with very low transparency and high legal uncertainty -

15 July 2025 | Policy Analysis

Steps to reform emergency medical services in Slovakia -

22 July 2024 | Country Update

Political interference in the Slovak health system -

16 February 2024 | Policy Analysis

Slovakia’s Health Care Surveillance Authority lacks institutional stability and independence

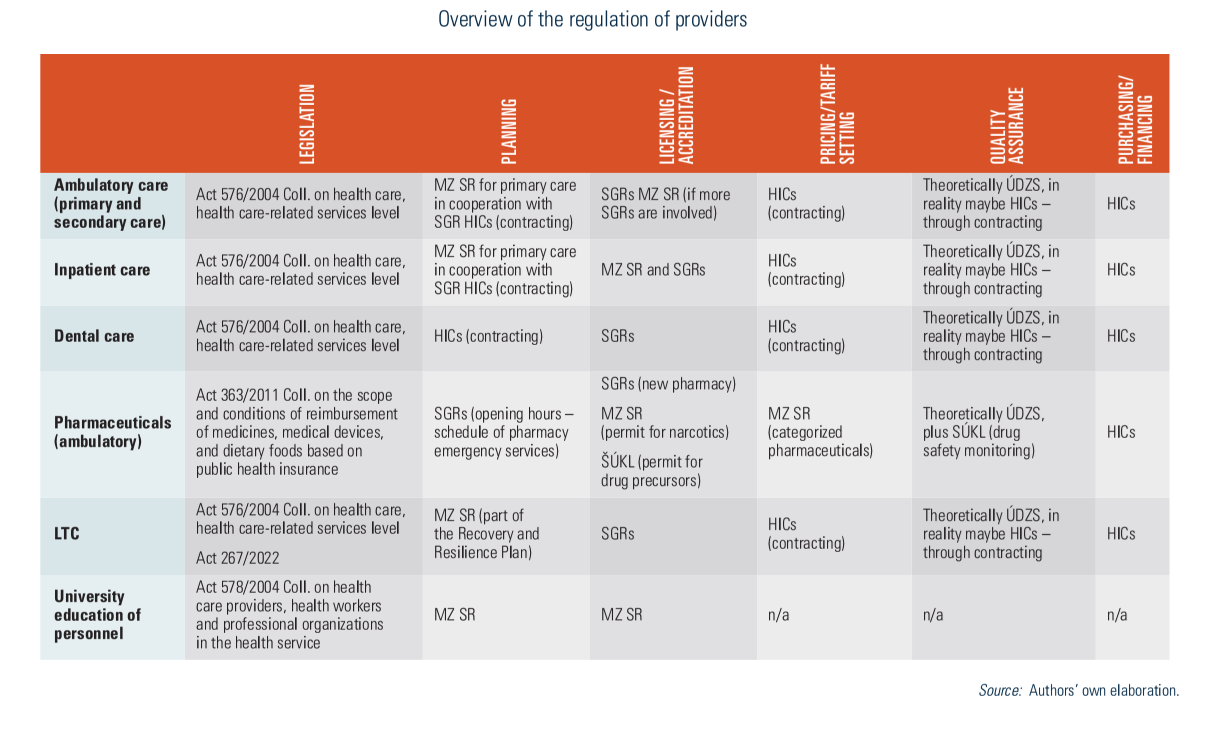

2.7. Regulation

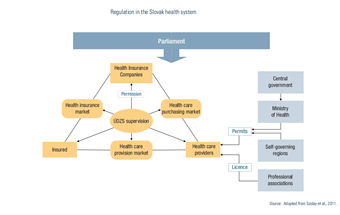

The main actors include parliament, the government, MZ SR, SGRs and ÚDZS. The regulatory environment is significantly shaped by parliamentary laws, including the Commercial Code, the Civil Code and the Labour Code. As executive bodies, the government and MZ SR enact regulations and decrees with legal liability and enforcement. ÚDZS is responsible for monitoring insurance, purchasing and providers (see Fig2.3). The Constitutional Court rules on whether laws conflict with the constitution, which stipulates that every person shall have the right to protect their health.

Fig2.3

Slovakia is facing a major public procurement controversy involving the tendering of its emergency medical services. The EUR 2 billion contract, covering both ground and air ambulance operations from 2025 to 2031, has become the largest healthcare tender of the current government – and is now mired in allegations of cronyism, lack of transparency and possible breaches of procurement law. Political tensions, media scrutiny and prosecutorial involvement have converged to make this one Slovakia’s most significant governance crises of 2025.

Tender overview

The Operational Centre of the Emergency Medical Service, on behalf of the Ministry of Health, launched the tender to allocate licences for 344 ground ambulance stations and 7 air ambulance bases nationwide in May 2025. The aim was to ensure the provision of high-quality, continuous emergency services across Slovakia. The winning bidders would secure operational rights for a six-year period, with the contract value estimated at EUR 2 billion (The Slovak Spectator, 2025a).

Transparency concerns

Criticism quickly emerged from opposition parties, the Slovak Medical Chamber and transparency watchdogs. They highlighted opaque selection procedures, including a refusal to disclose the names and qualifications of tender committee members.

In July 2025, preliminary results of the tender and the names of the commission members were leaked to the media, which confirmed concerns about poor transparency and fairness of the tender (The Slovak Spectator, 2025a).

One particularly contentious claim is that the tender process might be structured to favour certain bidders, notably Agel SK, Slovakia’s second-largest private healthcare provider, and a relatively unknown entrant, Emergency Medical Solutions (EMS). Both have reportedly been in positions to gain a disproportionately large share of contracts (The Slovak Spectator, 2025b). EMS was later proven to be linked to the second largest coalition party, HLAS-sociálna demokracia, which also nominated (as of this writing) incumbent Minister of Health, Kamil Šaško.

As a consequence, on 8 August 2025, Penta Hospitals, Slovakia’s largest private healthcare network, withdrew its bid, citing serious concerns over transparency and suggesting possible breaches of EU procurement law (The Slovak Spectator, 2025b).

The Slovak National Party (SNS), another governing coalition partner, demanded not only the cancellation of the tender but also the resignation of Health Minister Šaško. Prime Minister Robert Fico publicly acknowledged that the process could be scrapped or restarted if doubts persisted (TASR, 2025).

The General Prosecutor’s Office, led by Maroš Žilinka, initiated a preliminary review into the tender process. This action signals potential criminal investigations for alleged mismanagement of public funds and violations of procurement rules (The Slovak Spectator, 2025b).

Nevertheless, the management of the Operational Centre of the Emergency Medical Service delivered the results of the tender to the Ministry of Health on 11 August, thereby de facto announcing the successful selection procedure. On the same day, Minister of Health Šaško, announced that he would not sign it and would cancel the tender procedure, and would come up with an alternative for procuring emergency services in Slovakia, pending agreement within the governing coalition. Conclusions of such discussions are expected by the end of August 2025.

The opposition and experts claim that Health Minister Šaško could not terminate the tender and did so in violation of the law, which may cause the bidders to suffer lost profits, and are therefore demanding his resignation (TASR, 2025b).

Authors

References

The Slovak Spectator (2025a) News digest: Unqualified officials, secret committees. Ambulance tender raises red flags. SME.sk. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/politics-and-society/c/news-digest-unqualified-officials-secret-committees-ambulance-tender-raises-red-flags (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

The Slovak Spectator (2025b) News digest: Ambulance tender turmoil – Penta walks, prosecutor limbers up. SME.sk. Available at: https://spectator.sme.sk/politics-and-society/c/news-digest-ambulance-tender-turmoil-penta-walks-prosecutor-limbers-up (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

TASR (2025) Ambulance tender scandal: Political pressure mounts, PM and SNS weigh in. TASR. Available at: https://www.tasr.sk/tasr-clanok/TASR%3A2025080700000344 (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

TASR (2025b) According to Šaško, the tender for ambulances was cancelled in accordance with the law. “Anyone who questions this is lying”, he said. PRAVDA. Available at: https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/763156-sasko-tender-na-zachranky-bol-zruseny-zakonnym-sposobom Accessed: 15 August 2025).

In 2023, total out-of-pocket spending (OOP) in Slovakia reached EUR 1.7 billion EUR, and just over 18% of current heealth expenditure. At the same time, OOP payments are legally inconsistent, economically inequitable and lack transparency (see Table 1). Analysis of OOP spending reveals several key issues:

Low transparency and information asymmetries

Patients often do not know what exactly they are entitled to, do not understand the differences between a fee and a co-payment, or betweenstandard and above-standard service. Patients are often not informed by providers of these differences. Patients are often not issued receipts in practice, further reducing transparency.

There is also a variation in patients‘ readiness to pay, with some unwilling or unable to do so. Some are unwilling based on the principle of free healthcare at the point of service, while others, especially in poor regions, simply cannot afford to pay. There are also those willing to pay OOP, giving them priority and more adequate consultation times, scheduled appointments, and an individual, higher-quality approach.

Gaps in regulation, inconsistent approaches and legal uncertainties

There legal uncertainty surrounding the interpretation regarding providers’ ability to charge fees. After approximately 600 amendments since their adoption, laws 576, 577, and 578 of 2004 (core laws underpinning the major 2004 health system reform) create contradictory motivations for providers.

As stated by providers, a main reason for rising fees is due to insufficient reimbursements from insurers, leading them to seek alternative sources of funding to try to maintain levels of care quality. Other given reasons include rising staff wages (especially in public hospitals), the introduction of a transaction tax, general inflation across the economy and increasing energy costs.

Beginning in 2006, legal restrictions against direct payments were introduced. However, in practice, a chaotic “fee jungle” has emerged, with exploitation of numerous legal loopholes. This is also reflected in the varying levels of patient information (differing communication and price list publication methods), reducing predictability of patient costs.

Furthermore, the absence of regulation has led to variability in the fees charged among providers even within the same specialty. Price lists reveal regional differences: the highest charges are in Bratislava (sometimes multiple times higher), while in smaller towns or rural areas, fees tend to be lower or nonexistent.

Finally, an outdated performance catalogue does not reflect technological progress nor current market prices for materials. Notably, the catalogue was originally intended as a tool for introducing innovation (for example, telemedicine, AI, interventional radiology), not solely as a pricing mechanism.

Table 1: Legislative anchoring of direct payments and their relationship to public health insurance

| Occurrence of direct payment | Purpose of direct payment | Legislative basis |

| Before provision | Patient management | Act 576/2004 allows for charging for services beyond standard public coverage. However, annual care program services may be covert payments for services that should be free (Act 577/2004 prohibits fees for appointment scheduling, priority treatment, and administrative tasks). There are often collected by intermediaries (not the providers themselves); the healthcare service itself is reimbursed by an insurer. |

| Reservation portal | Legal loophole: current laws prohibit providers from charging for scheduled appointments.

Exploited by third-party private companies offering booking systems independent from the state and healthcare providers. |

|

| During provision | Fees for services related to care provision. | Regulated in §38 of Act 577/2004 in which Slovakia’s Constitutional Court confirmed that such charges are constitutional. |

| Co-payments for medicines, medical aids, durables and materials and dietetic food | Yes, most clearly regulated type.

Defined entitlements and transparent costs for both insurer and patient. |

|

| Direct payments to non- contracted providers | Governed by commercial code | |

| Price list fees | Partially regulated: not clearly defined in Act 577/2004 and indirectly referenced in Act 578/2004 requiring a public price list submitted to regional authorities Legally questionable in some cases (e.g., booking fees, prescription printing, spa referral), and often charged due to outdated reimbursement catalogue or lack of coverage in practice. | |

| After provision | Second opinion | While not explicitly defined in law or reimbursement systems, this is usually billed to insurers as a regular consultation or repeat exam. Sometimes charged separately, especially for advisory consultations. |

Source: Pažitný et al. 2025

An examination of the health financing in Slovakia’s specialized outpatient care sector reveals a fragmented landscape of patient cost sharing and direct payments. Legal ambiguity, regulatory inconsistency and increasing financial burdens for patients create significant challenges for fairness, transparency and sustainability. Key areas for reform, not only to simplify rules and protect patients but also to restore trust and ensure long-term sustainability of the health system could include the following:

- Legalizing all types of co-payments – being clearly defined in Act 577/2004 and making any fees and co-payments transparent and understandable.

- Extend informed consent – informing patients of the amount in advance and for what service they are paying.

- Issue receipts for every healthcare service provided – an invoice showing exactly what services were provided, and what is paid by the insurer and what by the patient.

- Health insurers must be involved – informing insurers about any patient charges collected by providers.

- Introduce effective financial protection via co-payment limits – with eligible populations clearly defined.

- Shift the control of patient charges to regional authorities – via legislation to allow them to define scope and amount of allowed fees locally.

- Creation of a reimbursement mechanism to help cover some administrative costs – with the involvement of the Slovak Social Insurance Agency, health insurers and providers

Authors

References

Pažitný, Kandilaki, Macko-Forgáčová, Löffler, Zajac: Direct Payments in Specialist Outpatient Care in Slovakia, June 2025

Smatana, M. et al. (2025) in press. Slovakia: health system review 2024. Health Systems in Transition

As explained in a previous policy analysis (https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/monitors/health-systems-monitor/analyses/hspm/slovakia-2016/slovakia-s-health-care-surveillance-authority-s-lacking-institutional-stability-and-independence), the Health Care Surveillance Authority (Úrad pre dohľad nad zdravotnou starostlivosťou in Slovak) plays an important regulatory role in the Slovak health system and is responsible for supervising health insurance, purchasing and healthcare markets. As with previous governments (no chair of the Health Care Surveillance Authority has served a full term since its establishment in 2004), the current government led by Prime Minister Robert Fico with Minister of Heath Zuzana Dolinková have politicized the role of the Authority’s chair. In February 2024, they used legislative amendments to §22 of Act 581/2004 to remove the then-incumbent Renáta Blahová.1, 2

More recently, the Fico government has adopted legislation to take effect on 1 August 2024 to change the criteria of who can serve as director of the National Institute for Value and Technologies in Healthcare (NIHO or Národný inštitút pre hodnotu a technológie v zdravotníctve), which was established in 2022 and is responsible for Health Technology Assessment in Slovakia. The new criteria specify that only a doctor or pharmacist could serve as head of the HTA agency (leading to the dismissal of the current head, Michal Staňák); the legislation also enables the Minister of Heath to dismiss the agency’s director at any time and without cause.

Besides the political sphere pushing itself into the decision-making levels of these two seemingly independent organizations within the health system, the current government has also used their existing authority to make the following changes in healthcare institutions and providers around the country since coming into office in October 2023 (the dates refer to when the officials were dismissed or replaced):

- Tomáš Janík, director of Faculty Hospital Trenčín, 14 November 2023.3

- Vladislav Šrojta, director of Faculty Hospital Trnava, 30 November 2023.4

- Pavol Bartošík, general director of Central Slovak Institute of Heart and Vascular Diseases (Stredoslovenský ústav srdcových a cievnych chorôb), 5 December 2023.5

- Ľubomír Šarník, director of Faculty Hospital Prešov, 6 December 2023.6

- Jozef Tekáč, director of Faculty Hospital Poprad, December 2023.7

- Eduard Dorčík, director of the hospital in Žilina, December 2023.8

- Peter Potůček, director of State Institute for Drug Control (Štátny ústav pre kontrolu liečiv), 31 December 2023.9

- Ľubica Hlinková, general director of VšZP (Všeobecná zdravotná poisťovňa), the state-owned Health Insurance Company, 10 January 2024.10

- Peter Lukáč, director of National Centre for Health Information (Národné centrum zdravotníckych informácií), 10 January 2024.11

- Ivan Kocan, director of University Hospital Martin, 10 January 2024.12

- Július Pavčo, director of Emergency Medical Service Operations Centre (Operačné stredisko záchrannej zdravotnej služby), 31 January 2024.13

- Renáta Blahová, Chair of Health Care Surveillance Authority, 6 February 2024.14

- Michal Fajin, director of Faculty Hospital Nitra, 14 February 2024.15

- Matej Mišík, chief of the Institute for Healthcare Analyses (Inštitút zdravotných analýz) at the Ministry of Health was revoked on 20.6.2024 without any reason. The Institute focuses on: epidemiological studies and data analysis, sector analysis and health policies, implementation of optimization of the hospital network and the development of the DRG reimbursement mechanism.16

- Michal Staňák, director of NIHO, according to legislation set to take effect on 1 August 2024, enabling the Minister of Health to dismiss the NIHO at any time and without giving a reason. The Ministry of Health has already published the announcement for the selection procedure for the position of the new director.17

Authors

References

1. https://spectator.sme.sk/c/23346445/slovak-health-minister-direct-power-independent-body.html

5. https://www.health.gov.sk/Clanok?mz-suscch-vedenie-nove

6. https://domov.sme.sk/c/23281567/fajin-nemocnica-nitra-dolinkova-pellegrini-hlas-rozhovor.html

7. https://domov.sme.sk/c/23272033/zuzana-dolinkova-zdravotnictvo-nemocnice-cistky.html

8. https://dennikn.sk/minuta/3744432

11. https://zive.aktuality.sk/clanok/SdYXsqi/odvolali-riaditela-nczi-kto-bude-na-cele

13. https://www.health.gov.sk/Clanok?operacne-zachranka-riaditel

14. https://www.tyzden.sk/zdravotnictvo/106251/vlada-odvolala-sefku-udzs-na-jej-miesto-zasadne-palkovic

15. https://domov.sme.sk/c/23281567/fajin-nemocnica-nitra-dolinkova-pellegrini-hlas-rozhovor.html

The Health Care Surveillance Authority (HCSA) plays an important regulatory role in the Slovak health system. Responsible for supervising health insurance, purchasing and healthcare markets, HCSA chairs are elected for five-year terms and are theoretically independent, given an irrevocable mandate as chair. This independence was written in the original legislation from 2004 that specified that a chair’s mandate could only end due to their own resignation, by power of the government (only after the chair committed an intentional crime) or the chair died.

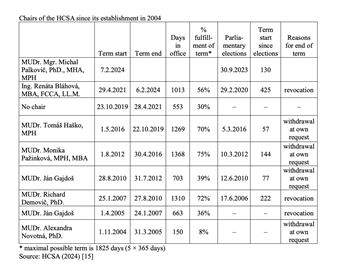

Successive governments over the past two decades, however, have worked to install chairs corresponding to their particular (political) needs, given the prominent role the HCSA plays in regulation. Thus, through the years, changes of chair have become common after legislative amendments to §22 of Act 581/2004, the law that defines the conditions of a chair’s appointment and the revocation process (for example, clauses permitting the removal of the chair were added regarding subjective evaluations of the chair’s performance, or general (subjective) views of the Government that the chair cannot complete the mandate due to personal, moral or professional reasons). Since the establishment of the HCSA 20 years ago, not one of the seven chairs have served a full term (see Table 1): their mandates were either revoked (3x) or they resigned on their own (4x).

As no chair has served a full term, the record of longest term was Monika Pažinková, who served 75% of her term (2012–2016), while the shortest was under the first chair, Alexandra Novotná (2004–2005). Additionally, and crucially, the HCSA had no chair from the end of 2019 through the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, a total of 553 days. Chairs are typically changed following parliamentary elections, so there is little overlap of incumbent chairs continuing to serve in a new government, even if their term is ongoing. There have also been four instances of new HCSA chairs coming into office within the first five months after parliamentary elections.

The four cases of chairs withdrawing from leading the HCSA include:

- Alexandra Novotná served for 150 days in 2005 (8% of the planned mandate duration). After establishing and stabilizing the institution, she relinquished her position to the State Secretary of the Ministry of Health, Ján Gajdoš, who decided to assume the role he had originally planned to take. As a result of her resignation, a position exchange occurred with the then-State Secretary, Ján Gajdoš [1].

- Ján Gajdoš after 703 days in 2012 (39% of planned term). His resignation came in reaction to an amendment of law 581/2004 that once again enabled the Minister of Health to remove the chair of the HCSA. Gajdoš cited disagreements with the politicization of the office of HCSA Chair and a de facto subordination to the Ministry of Health [2].

- Monika Pažinková after 1368 days in 2016. Pažinková became a symbol of patronage in office, being closely connected to businessmen from the city of Košice and the Smer political party [3].

- Tomáš Haško after 1269 days in 2019 because of irregularities in tender process for emergency vehicles that he oversaw [4].

The three cases of governments revoking mandates for HCSA chairs include:

- Ján Gajdoš after 663 days in 2007. While the Health Minister at the time (Valentovič) stated Gajdoš’ dismissal was the result of the office's performance given the state of healthcare in Slovakia at the time, Gajdoš himself considered it to be political, not professional [5].

- Richard Demovič after 1310 in 2010. He was dismissed by Health Minister Uhliarik using the same reasoning (poor performance) [6].

- Renáta

Bláhová after 1013 days in 2024. The Health Minister’s (Dolinková)

dismissal justified this by saying that Bláhová does not meet the

qualifications to be chair as required by law and that she is a

political nominee, appointed to the position of chair without a

selection process [7].

Increasing the institutional stability and independence of the regulatory frameworks (see for example, Balík (2012 [8])) and environment in Slovakia requires

- reestablishing the HCSA Chair’s independence by abolishing the legislative clause on their removal by the government without formal reason,

- strengthening the competences of the HCSA’s Board by transferring the decision-making powers from the chair, making the HCSA a collective decision-making body and not a single “one-person show”, and

- transferring the HCSA’s supervisory role over health insurance companies (HICs) to the National Bank of Slovakia and thus fulfilling an initial plan from 2004 when the HCSA was established.

The National Bank of Slovakia is an independent financial institution that could effectively supervise the financial situation of HICs. This would achieve the diversification of authority and preserve independence and resistance to political power, which is characteristic of regulators in other countries with competition-based systems (that is, multiple health insurers), like Germany (Federal Office for Social Security [9] and Federal Financial Supervisory Authority [10]), Switzerland (the Federal Office of Public Health [11] and the Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) [12]) and the Netherlands (The Dutch Healthcare Authority [13] and the Netherlands National Bank [14]).

Table 1

Authors

References

[1] https://hsr.rokovania.sk/329/125-schodze-vlady-slovenskej-republiky/?csrt=10869901077926702124

[2] https://www.trend.sk/spravy/sef-uradu-pre-dohlad-vzdal-funkcie

[4] https://domov.sme.sk/c/22242684/vlada-sr-odvolala-tomasa-haska-z-funkcie-predsedu-udzs.html

[5] https://domov.sme.sk/c/3108072/gajdos-povazuje-dovody-na-svoje-odvolanie-za-politicke.html

[6] https://domov.sme.sk/c/5521713/demovic-odchadza-z-uradu-nerad.html

[8] http://www.hpi.sk/cdata/Publications/regulacny_ramec_a_udzs.pdf

[9] https://www.bundesamtsozialesicherung.de/de

[10] https://www.bafin.de/EN/DieBaFin/diebafin_node_en.html

[12] https://www.finma.ch/en/authorisation/insurers/getting-licensed/health-insurance

[13] https://www.nza.nl/english

[15] https://www.udzs-sk.sk/urad/zakladne-informacie/predstavitelia-uradu

2.7.1. Regulation and governance of third-party payers

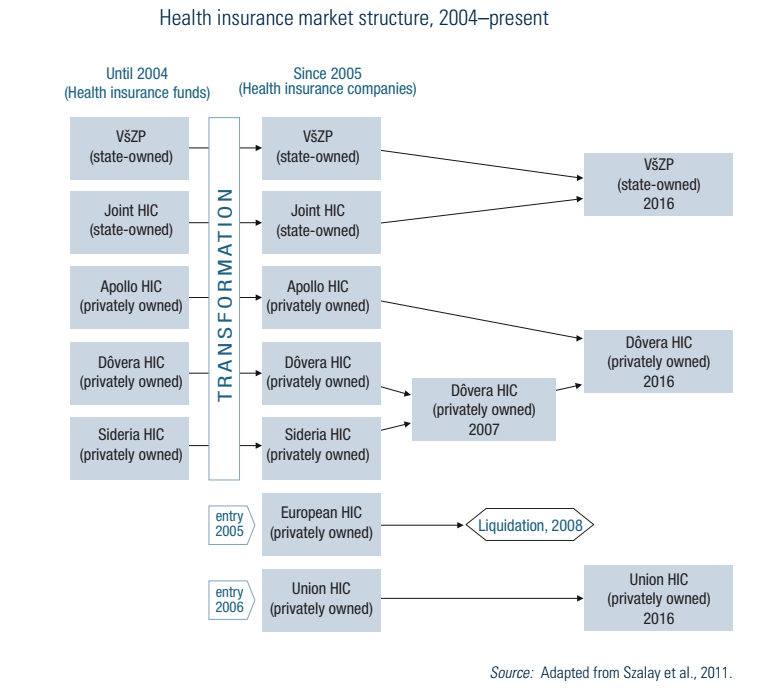

As of 2004, HICs operate as joint-stock companies. HICs collect contributions, pool resources and purchase services. They must operate nationwide, although market shares show significant regional variation. This results in regional differences between HICs’ negotiating power vis-à-vis providers.

ÚDZS issues licences for HICs. Legal conditions include an issued share capital (minimum €16.6 million) and transparent leadership. Their shareholders appoint their Boards of Directors and Supervisory Boards. Regulations apply to the shareholders’ structure, staffing and purchasing policies, as well as to the financial management of the HICs. ÚDZS enforces these regulations and may impose sanctions. In 2024 VšZP was threatened with sanctions owing to poor economic performance and the threat of insolvency.

HICs, like all other joint-stock companies, are obliged to undergo an external audit of their accounting records. They can propose an auditor, but ÚDZS may refuse this and assign one. ÚDZS submits biannual reports on the financial administration of HICs, as well as an annual budget proposal to both MZ SR and the Ministry of Finance. All HICs must submit their business plans to ÚDZS as well as MZ SR and the Ministry of Finance, and must publish annual reports via the Commercial Register. HICs must publish all contracts with providers on their websites.

The state, represented by the government and MZ SR, plays an important role in regulating HICs (as the government can appoint and dismiss the ÚDZS Chair), defining the (minimum) benefits package via legislation, setting reimbursement policies for drugs, medical devices and dietetic food, and determining whether user fees apply and maximum waiting lists. As MZ SR is the only shareholder in VšZP (the largest HIC), the Ministry has influence over the insurer’s operating and purchasing policies, and, due to its market share (54.8%), over a large segment of the health insurance market.

HICs must meet all the health care needs of their insured before being allowed to pay out dividends to shareholders. Initially, after the 2004 reform (see Section 2.1.2), two profit-oriented HICs entered the market, two merged to consolidate their portfolios, and one ceased operating. Beginning in 2008, HICs had been obliged to use all profits towards purchasing services in the following year, though the possibility of making a profit from public health insurance was reintroduced in 2011 after a Constitutional Court ruling. In 2012 the Dutch company Achmea, owner of the Union HIC, won an international arbitration case against Slovakia and Slovakia had to pay €25.5 million in damages as a result of the profit ban between 2008 and 2011.

HICs’ profits are an often-reoccurring topic without a clear conclusion. Since 2023 HICs can keep only a small part of their income as profit. Specifically, they’re allowed to retain up to 1% (after the application of a risk adjustment mechanism) of the total insurance premiums they collect. If they make more than that, the extra money does not go to shareholders – it must be put into a special fund called the health quality fund. This fund is used to pay for health services that improve the quality of care for insured people. Furthermore, HICs are required to use at least 95.1% of prescribed premiums for care-related costs.

After two more mergers, the market (as of 2024) consists of the state-owned VšZP and two privately owned HICs (see Fig2.4). The market share of VšZP dropped from 76% in 2005 to 54.8% in 2023.

Fig2.4

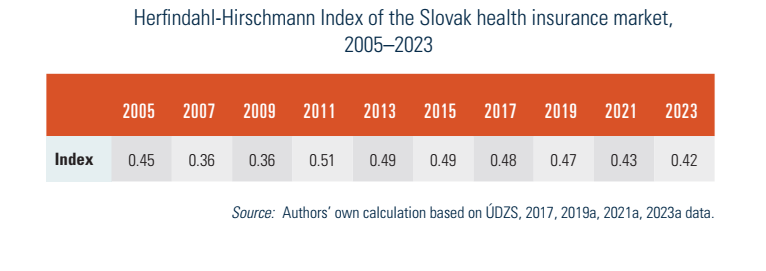

With only three HICs operating in Slovakia, the health insurance market was very concentrated in 2023, with a Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index of 0.42. This indicator measures the amount of competition among firms in an existing market in relation to their sizes. As such, the index can range from 0 to 1.0, moving from a large number of very small firms to a single monopolistic producer (see Table2.2). Above 0.25, a market is seen as highly concentrated.

Table2.2

2.7.2. Regulation and governance of provision

Regulating care focuses on three components: structure, processes and results.

Structure

MZ SR sets minimum criteria for material and technical equipment, as well as qualifications and personnel criteria. The following conditions need to be met to provide health care in Slovakia: (1) a permit to operate the facility and (2) a licence from the relevant professional chamber for the various professionals working there. Both can be requested if material, technical, staff and qualification requirements are met.

Permits for many inpatient and outpatient facilities are generally issued by SGRs (see Table2.3). However, the permits for the biggest hospitals are exempted from this rule and are issued by MZ SR. Disputes are settled by MZ SR, which also issues permits for specialized hospitals, facilities for biomedical research, tissue units, biological banks and reference laboratories. Providers willing to operate in several SGRs also fall under MZ SR’s regulation.

Table2.3

Permits are granted indefinitely, during which providers are obliged to observe specific legal conditions. Emergency medical service and outpatient emergency service providers are an exception; they can only obtain a permit from MZ SR after winning a tender, while financing from HICs and an identified operating territory must be secured.

Independent health professionals who function as entrepreneurs may provide services based only on their licence to perform in an independent medical practice.

Almost all GPs and the vast majority of outpatient specialized physicians provide services in private practices. The state is the owner of the largest (mostly university and faculty) hospitals, almost all of which are “contributory organizations” (i.e., not-for-profit legal entities). Five state-owned facilities were transformed into joint-stock companies by the 2004 reforms.

Irrespective of legal form, all providers need to compete for contracts with HICs based on quality criteria and prices. By delegating the competences to establish a network of providers from MZ SR to HICs, selective contracting was enabled in the Slovak health system. To guarantee accessibility of providers, a minimum network requirement is set by the government to influence capacity planning. This network is based on calculations of the minimum number of physicians’ posts in outpatient care and a minimum number of hospital beds for each SGR. Minimum capacities are calculated per capita.

Process

MZ SR requires providers to have written documentation concerning their quality system, in order to reduce provision shortcomings. However, MZ SR has so far not enforced this and providers are currently not required to undergo external monitoring, or to publish their financial results or quality indicators.

A certain shift in the regulation of processes occurred after 2018, when MZ SR started issuing standard diagnostic guidelines and standard therapeutic guidelines not constituting a generally binding regulation. The standards are issued gradually and should cover a total of 150 specialty areas (MZ SR, n.d.(a)).

In 2025 a delayed regulation on waiting lists is planned for implementation (Dôvera, 2024). It should operate as follows.

- The patient agrees with the provider, and the provider submits a proposal for planned care. The HIC checks and approves the proposal and informs the patient.

- Each proposal has its own identifier, assigned by the provider for mutual communication between the provider, the HIC, the patient and NCZI.

- Depending on the service, the period of time availability is determined; this starts on the day the proposal is submitted.

- The provider will assign the first available date. If the patient’s condition is serious or the procedure requires multiple hospitalizations, the provider may choose an earlier date. The patient can also request a later date.

- If the service is not available during the defined period and the patient wants an earlier date, they can try to contact another provider. If the patient goes out of network, there may be additional fees. If the patient decides to wait, the agreed performance date remains valid.

Results

This is limited to issuing quality indicators on providers, which serve as criteria for selective contracting. Quality indicators are published yearly and are developed by MZ SR in cooperation with professional organizations, HICs and ÚDZS. According to ÚDZS, the data collected by providers have low validity, which results in the low credibility of the providers’ ranking.

Suspicions of malpractice are investigated by ÚDZS. If malpractice is confirmed, ÚDZS can impose sanctions in cooperation with SGRs and MZ SR. In case of a suspected crime, ÚDZS files a motion to bring a contested issue before a court for decision. Such incidents are published by ÚDZS in case report summaries.

General overview

In March 2025, the Slovak Government approved the most significant reforms to the emergency medical services (EMS) system in over two decades. Although the initial implementation date was set for 1 January 2025, the new legislation will be introduced in phases, and commenced on 15 April 2025. It includes structural changes to ambulance services, the development of a new ambulance network and the introduction of a new professional role.

Structural changes to ambulance services

Several new types of ambulance crews will be deployed. One of the most notable is the hybrid rapid medical assistance (RLP)/rapid medical aid (RZP) model, whereby a physician-staffed RLP unit will operate during daytime hours, and an RZP crew without a physician at night. This measure is designed to optimize the use of physicians, whose availability in the Slovak health system is limited.

Another innovation is the RZP crew with extended-scope specialist paramedics. These paramedics will be authorized to perform advanced medical interventions previously reserved for physicians, with the intention of accelerating care delivery, particularly in remote or underserved areas.

The reform also introduces specialized ambulance types, including:

- Planned transport ambulances for non-emergency inter-hospital transfers and selected low-acuity primary calls, freeing doctors and paramedics for acute cases.

- Mobile paediatric intensive care unit ambulances, operated by tertiary paediatric healthcare facilities, to ensure critically ill children are transported by personnel trained in paediatric emergency medicine.

- Emergency medical assistance ambulances for repatriation (if a patient is abroad and needs transport back to Slovakia) and other non-insurance-covered transport needs, such as medical coverage at social, cultural and sporting events.

Development of a new ambulance network

The EMS network will be redesigned based on a mathematical optimization model that uses historical data on response times, call volumes, call types and geographic distribution of incidents. This model will propose optimal crew deployment to minimise response times and maximize coverage.

As a result, the number of ground ambulance service stations in Slovakia will increase from 321 to 344 from the next tendering period, beginning in Autumn 2025. Additionally, the reform specifies more precise regulations for the location of EMS stations in regional capitals to improve equitable access across urban areas and surrounding municipalities.

A commission within the Ministry of Health will monitor compliance with newly established quality indicators for both EMS providers and emergency dispatch centres. The first set of indicators was published in the Official Gazette in mid-2025, with systematic measurement scheduled to commence in 2026.

Introduction of a New Healthcare Professional Role

The legislation also creates a new category of healthcare worker: the transport assistant. Transport assistants, similar in status to nurses within the EMS system, will be formally registered with the Slovak Chamber of Emergency Medical Technicians. This ensures both professional representation and access to continuous professional development opportunities.

Another key feature of the reform is the planned introduction of a new emergency telephone number, 116117, in January 2026. This number will handle non-urgent medical inquiries, thereby alleviating the workload on the existing emergency number 155, which will continue to be reserved for urgent, life-threatening cases. The aim is to enable EMS teams to concentrate their resources on critical incidents requiring immediate intervention.

References

Fekete, B. (2025) Vláda schválila najväčšiu reformu záchraniek za posledné roky. Čo nás čaká? (The government has approved the biggest reform of the emergency services in recent years. What can we expect?). MEDICINA Trend. Available online from: https://medicina.trend.sk/2025/03/12/vlada-schvalila-najvacsiu-reformu-zachraniek-za-posledne-roky-co-nas-caka

Jeseňák, Š., Gaston, I. and Majerský, F. (2025) František Majerský & Gaston Ivanov: Najväčšia reforma záchrannej zdravotnej služby za 20 rokov s cenovkou 1,2 miliardy € (František Majerský & Gaston Ivanov: The biggest reform of the emergency medical services in 20 years, with a price tag of €1.2 billion). Ozdravme.sk Available online from: https://www.ozdravme.sk/Dokument/101831/frantisek-majersky-gaston-ivanov-najvacsia-reforma-zachrannej-zdravotnej-sluzby-za-20-rokov.aspx

2.7.3. Regulation of services and goods

Basic benefits package

The Slovak Constitution guarantees access to health care and assumes that the scope of covered health services should be defined by the law (in parliament). The definition of the basic benefits package is very broadly outlined in Act No. 577/2004 on the scope of health care reimbursed under health insurance and payments for health care services. After the Constitutional Court ruled to enable more precise definitions of patient entitlement through subsidiary regulations, several decrees have been implemented to govern specific sectors within health care services but there is no single list of services that constitutes the basic benefits package.

HTA

Since 2022, novel technologies are examined by NIHO. NIHO prepares evaluations and analyses based on established European methodologies (EUnetHTA) according to evidence-based medicine. Their assessments are then passed to the respective reimbursement committee, where members issue final recommendations and MZ SR issues decisions. In regard to pharmaceuticals, its key role is to prepare evaluation of medicines with a potential impact of more than €1.5 million per year for the purposes of categorization (NIHO, 2024).

2.7.4. Regulation and governance of pharmaceuticals

Pharmaceuticals must have an authorization from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), or the national-level ŠÚKL. ŠÚKL closely monitors the safety of drugs in Slovakia and is the national competent body responsible for pharmacovigilance. Monitoring includes reporting of adverse reactions and requiring reports from pharmaceutical companies. Prescribing physicians are obliged to report any adverse effects. In 2023 there were 874 reports received by ŠÚKL, out of which 240 were deemed serious. Another 1640 reports were from the European database reported by pharmaceutical companies (ŠÚKL, 2023).

Market authorization holders are obliged to report adverse effects of drugs. Each market authorization holder appoints a person responsible for pharmacovigilance. In addition to physicians, reporting adverse effects applies to pharmacists, nurses and patients. ŠÚKL has the right to suspend distribution or withdraw a pharmaceutical from the market, can suspend the registration for 90 days or terminate it.

ŠÚKL is in charge of pharmaceutical advertising standards. The content of general public advertisement may not give the impression that medical examination is not necessary or that pharmaceutical effects are guaranteed.

The decision as to whether a pharmaceutical will be covered by social health insurance lies with MZ SR’s reimbursement committee. The decision is made after an assessment of the pharmaceutical (see Fig2.5). A similar process is used for medical devices and dietary products. MZ SR centrally regulates the scope of services provided by health insurance by defining the list of fully or partially reimbursed drugs, medical devices and dietary products.

Fig2.5

First, the marketing authorization holder must submit comparative data on the pharmaceutical, including effectiveness, safety and pharmacoeconomic data. In line with recommendations from MZ SR, the pharmaceutical is assessed using cost-minimization, cost-effectiveness and cost–utility analysis. The recommended threshold of a cost-effective new technology was set at 2x, 3x, 5x respectively 10x GDP at current prices from two previous years according to ŠÚ SR, and thus pharmaceuticals with lower costs per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) are considered cost-effective (Slov-Lex, 2022).

Second, each pharmaceutical is evaluated according to its anatomic, therapeutic and chemical classification by a specialist working group that evaluates the effectiveness, safety and importance of each pharmaceutical. One working group evaluates the pharmacoeconomic properties of the pharmaceutical. The results produced by the specialist working groups serve as the context for the decisions of the Reimbursement Committee for Medicinal Products. Of its 15 members, four are representatives of MZ SR, six are representatives of the HICs, three are representatives of the professional public, one is a patient representative and one is from NIHO.

Lastly, the Reimbursement Committee puts forward proposals for inclusion, non-inclusion, exclusion or change in the status to the positive list of categorized medicines (those that are reimbursed), along with proposals for reimbursement level, co-payment and conditions for reimbursement. The applicant receives written information on the results of the reimbursement decision, and may appeal the decision. The process of reimbursement decision-making for drugs is updated and published monthly; requests for inclusion in the official price list may be submitted at any time.

Pricing

Slovakia operates a reference pricing system for pharmaceuticals. Reimbursement is set as the maximum price for a standard daily dose in the reference group. The definition of a given reference group is very narrow. All pharmaceuticals included in the reference group contain the same active substance and are administered uniformly. In certain cases, the Reimbursement Committee may decide to form a separate reference group for pharmaceuticals with different administering form and a different amount of active substance per dose. The prices of covered pharmaceuticals are regulated, in both the ambulatory and inpatient sectors. Commercial margins for reimbursed drugs are regulated and VAT is 5%. After obtaining an authorization to enter the market, the ex-factory price of the pharmaceutical is determined by MZ SR through external reference pricing. The ex-factory price may not exceed the average of the three lowest prices of the same pharmaceutical sold in the EU. The prices of over-the-counter (OTC) pharmaceuticals and prescription pharmaceuticals not covered by insurance have been deregulated.

Managed entry agreements

Before 2022, if the market authorization holder wanted a specific medicinal product to be reimbursed by public health insurance, they had to enter into managed entry agreements with all insurers. This process was burdensome and impeded the entry of certain innovative products.

Since the amendment to Act No. 363/2011 Coll. on the scope and conditions of the reimbursement of pharmaceuticals, medical devices and dietetic foods under public health insurance was approved in 2022, managed entry agreements have been established directly with MZ SR instead of with each health insurer individually. This change has shifted the responsibility for determining which therapeutic options are available in Slovakia directly to the state. The specifics of these agreements, including the highest reimbursement amount for a medicine by a health insurer, the total reimbursement limit from all insurers and any restrictions on indications or prescriptions, are now directly negotiated with MZ SR. Although this agreement is broad in scope, market authorization holders retain the ability to negotiate particular, more advantageous terms with individual health insurers.

Furthermore, the new legislation expanded the conditions under which managed entry agreements can be formed, streamlined the process of creating these agreements and revised the method for assessing the cost-effectiveness of medicines. As a result, it significantly promotes the shift of innovative medicines from the exceptional reimbursement regime to the standard one.

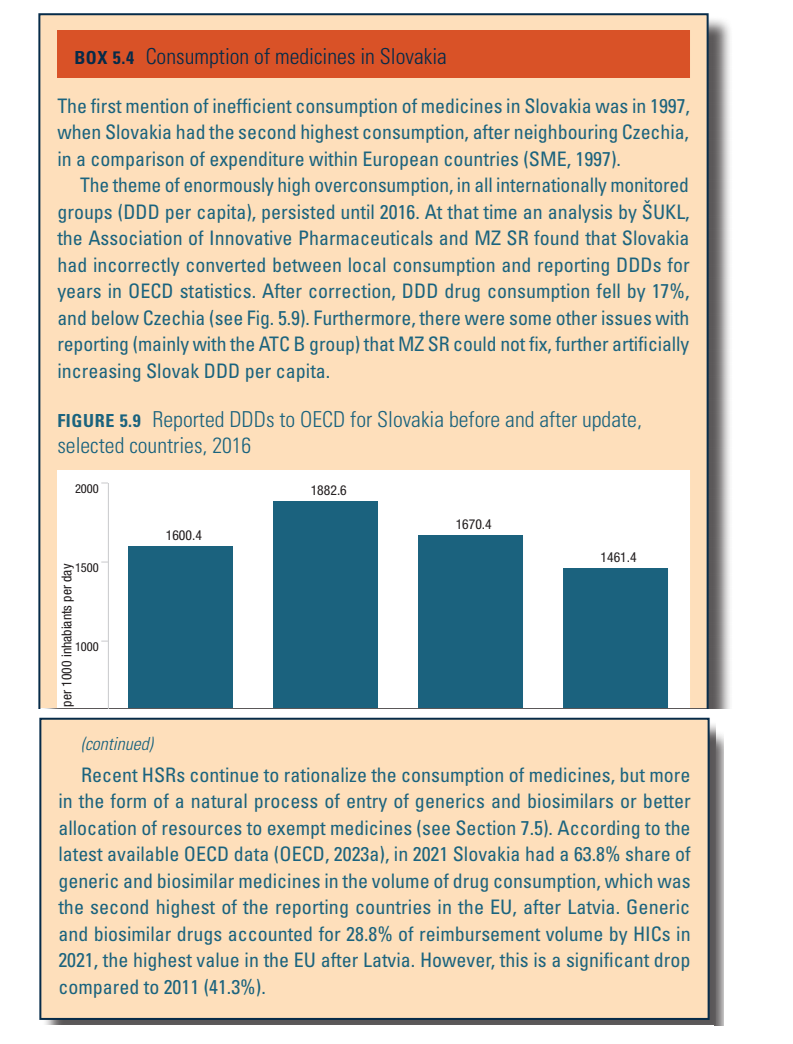

Generic and biosimilar drugs

Slovakia is one of the OECD and EU countries with above-average consumption of generic and biosimilar medicines in financial (payment from public resources) and quantitative (daily doses or number of packages) terms. The last decade, however, has seen a decline in generic and biosimilar consumption, in terms of both financial expenditure and quantity (see Box5.4 in Chapter 5). According to a regulation implemented in 2011 (Act no. 362/2011), physicians are obliged to prescribe the active substance of a medicine (by International Nonproprietary Names, not by brand names). Furthermore, pharmacists are obliged to inform patients about cheaper alternatives (generics) when filling a prescription. If the physician did not provide any reason not to use the generic substitute, the patient may choose the less expensive option under the supervision and advice of a pharmacist. However, physicians are allowed to add the trade name of the prescribed substance in the prescription form and pharmacists respect their preference. Thus, in practice, substitution for cheaper generic drugs is less common.

Box5.4

2.7.5. Regulation of medical devices and aids

Medical devices and aids (MDA) are assessed through a similar categorization process as described for pharmaceuticals. This includes the application by the marketing authorization holder of the medical device, evaluations by working groups and a reimbursement proposal prepared by the Reimbursement Committee.

MZ SR acts as regulator and defines the administratively defined price at which the medical device manufacturer or the importer is allowed to enter the Slovak market.

Prices of medical devices are subject to categorization and reference pricing and can be changed quarterly. In every subgroup, there is equal reimbursement for the whole subgroup, and there are medical aids with and without co-payments. The full list of categorizations is found at https://www.health.gov.sk/?zkszm.