-

15 July 2025 | Policy Analysis

Steps to reform emergency medical services in Slovakia

4.2. Human resources

General overview

In March 2025, the Slovak Government approved the most significant reforms to the emergency medical services (EMS) system in over two decades. Although the initial implementation date was set for 1 January 2025, the new legislation will be introduced in phases, and commenced on 15 April 2025. It includes structural changes to ambulance services, the development of a new ambulance network and the introduction of a new professional role.

Structural changes to ambulance services

Several new types of ambulance crews will be deployed. One of the most notable is the hybrid rapid medical assistance (RLP)/rapid medical aid (RZP) model, whereby a physician-staffed RLP unit will operate during daytime hours, and an RZP crew without a physician at night. This measure is designed to optimize the use of physicians, whose availability in the Slovak health system is limited.

Another innovation is the RZP crew with extended-scope specialist paramedics. These paramedics will be authorized to perform advanced medical interventions previously reserved for physicians, with the intention of accelerating care delivery, particularly in remote or underserved areas.

The reform also introduces specialized ambulance types, including:

- Planned transport ambulances for non-emergency inter-hospital transfers and selected low-acuity primary calls, freeing doctors and paramedics for acute cases.

- Mobile paediatric intensive care unit ambulances, operated by tertiary paediatric healthcare facilities, to ensure critically ill children are transported by personnel trained in paediatric emergency medicine.

- Emergency medical assistance ambulances for repatriation (if a patient is abroad and needs transport back to Slovakia) and other non-insurance-covered transport needs, such as medical coverage at social, cultural and sporting events.

Development of a new ambulance network

The EMS network will be redesigned based on a mathematical optimization model that uses historical data on response times, call volumes, call types and geographic distribution of incidents. This model will propose optimal crew deployment to minimise response times and maximize coverage.

As a result, the number of ground ambulance service stations in Slovakia will increase from 321 to 344 from the next tendering period, beginning in Autumn 2025. Additionally, the reform specifies more precise regulations for the location of EMS stations in regional capitals to improve equitable access across urban areas and surrounding municipalities.

A commission within the Ministry of Health will monitor compliance with newly established quality indicators for both EMS providers and emergency dispatch centres. The first set of indicators was published in the Official Gazette in mid-2025, with systematic measurement scheduled to commence in 2026.

Introduction of a New Healthcare Professional Role

The legislation also creates a new category of healthcare worker: the transport assistant. Transport assistants, similar in status to nurses within the EMS system, will be formally registered with the Slovak Chamber of Emergency Medical Technicians. This ensures both professional representation and access to continuous professional development opportunities.

Another key feature of the reform is the planned introduction of a new emergency telephone number, 116117, in January 2026. This number will handle non-urgent medical inquiries, thereby alleviating the workload on the existing emergency number 155, which will continue to be reserved for urgent, life-threatening cases. The aim is to enable EMS teams to concentrate their resources on critical incidents requiring immediate intervention.

References

Fekete, B. (2025) Vláda schválila najväčšiu reformu záchraniek za posledné roky. Čo nás čaká? (The government has approved the biggest reform of the emergency services in recent years. What can we expect?). MEDICINA Trend. Available online from: https://medicina.trend.sk/2025/03/12/vlada-schvalila-najvacsiu-reformu-zachraniek-za-posledne-roky-co-nas-caka

Jeseňák, Š., Gaston, I. and Majerský, F. (2025) František Majerský & Gaston Ivanov: Najväčšia reforma záchrannej zdravotnej služby za 20 rokov s cenovkou 1,2 miliardy € (František Majerský & Gaston Ivanov: The biggest reform of the emergency medical services in 20 years, with a price tag of €1.2 billion). Ozdravme.sk Available online from: https://www.ozdravme.sk/Dokument/101831/frantisek-majersky-gaston-ivanov-najvacsia-reforma-zachrannej-zdravotnej-sluzby-za-20-rokov.aspx

4.2.1. Planning and registration of human resources

Since June 2022 MZ SR has been working on a national strategy for the planning and stabilization of human resources in health care, though it has not been published, discussed publicly or adopted (MZ SR, 2022b). On the other hand, the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family completed a project on “Sectorial managed innovation” in 2022, which presented a comprehensive set of detailed national standards for 193 health care professions, including information about the required compulsory educational level for each job (SRI, n.d.). This, however, took more a technical than a strategic approach. At the time of writing, there is no official strategy for human resources in health care and there is no mechanism for regulating the number of health workers in each category and specialization according to the population’s needs.

Human resource planning in hospitals is the responsibility of hospital management, and planning in outpatient care is the purview of HICs and SGRs. In hospitals (71 general and 45 specialized), physicians are employed as staff, whereas in outpatient settings they are usually self-employed or business owners of their clinics (NCZI, 2021). Trade unions have described the situation in hospitals as “lacking staff, exhausted medical professionals, unnecessary deaths and the need for dialogue”. This resulted in the strike action in 2022 (see Section 3.7.2).

Licensing and recognition

To obtain a licence, a physician must meet five criteria defined by law (Act 578/2004): (1) have full legal capacity; (2) be medically fit (annual check-up required after 65+); (3) be professionally educated (diplomas and certificates); (4) have integrity (proven through a criminal record check); and (5) be officially registered (maintained by the SLK). There are several types of licence, which differ from each other according to the medical field (SLK, 2024).

The application for the issuance of a licence is submitted to the regional chamber of which the doctor is a member. The regional chamber will issue a licence if the applicant has proven that all conditions have been met. Licence holders can also apply for a temporary suspension for a maximum of one year. To practise in the outpatient setting, a licensed physician must also submit an application to operate a practice to the relevant SGR (or MZ SR, if the physician wants to provide care in more than one SGR). There is no system of recertification of licences in the Slovak health system.

Education recognition systems have been adopted from EU legislation (Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications). Documents on certain specializations of physicians and dental practitioners, whose specialized training is harmonized across the entire EU, are recognized under an automatic system.

The recognition of a foreign diploma or qualification for the pursuit of regulated professions is handled by the Centre for Recognition of Diplomas at the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic, n.d.(a)). Recognition of any other educational qualifications of health care professionals acquired in non-EU Member States necessitates a further application for validation of their diploma followed by a supplementary exam to demonstrate the required skills (Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic, n.d.(b)). Applicants must also have working knowledge of Slovak; for health care professionals, MZ SR is responsible for the official language verification.

4.2.2. Trends in the health workforce

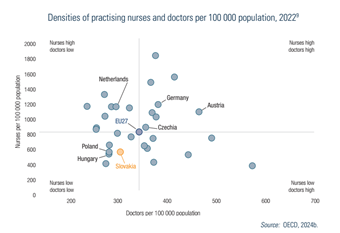

Compared to the EU average, Slovakia has low levels of practising doctors and nurses. Slovakia also lags behind Czechia, though has higher densities than the other V4 countries (Poland and Hungary) (see Fig4.2).[9]

Fig4.2

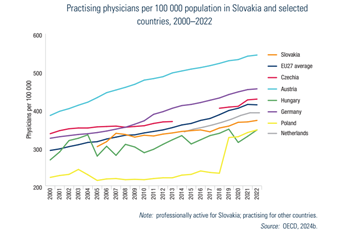

Slovakia reached its historical minimum in 2005 with 304 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants. In 2022 this improved to 372 per 100 000 (see Fig4.3). As a result of differing trends (fewer nurses with more doctors), the nurse-to-doctor ratio fell from 2.2 in 2000 to 1.5 in 2022. This is comparable to Hungary (1.6) and Poland (1.6), but significantly lower than Austria (2.0) or Czechia (2.1).

Fig4.3

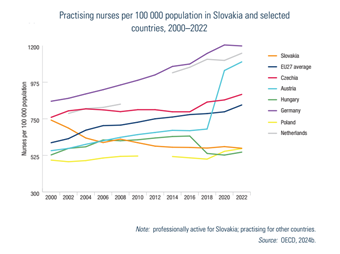

There is a clear long-term decline in the number of nurses. Low staffing of nurses, their age structure (and gradual retirement), emigration and low interest among younger generations are significant concerns. In 2000 Slovakia had 744 nurses per 100 000 inhabitants, while in 2022 it was only 569 per 100 000 (see Fig4.4). Estimations from the Chamber of Nurses and Midwives from 2023 are that Slovakia has a current shortage of 16 000 nurses and within 10 years the shortage will be 25 000 nurses (SITA, 2023a). The Chamber thus welcomed the simplified process for recognizing professional qualifications for nurses from Ukraine in mid-2023. In terms of leaving Slovakia to work elsewhere, Austria and Czechia present opportunities for nurses owing to more favourable working conditions and their proximity.

Fig4.4

The regional distribution of health professionals within Slovakia is very skewed (see Table4.6) – for example, the Bratislava Region has 6.6 doctors per 1000 inhabitants, while five regions have around 3 doctors per 1000 inhabitants. These regional disparities are also present among dentists, pharmacists and nurses.

Table4.6

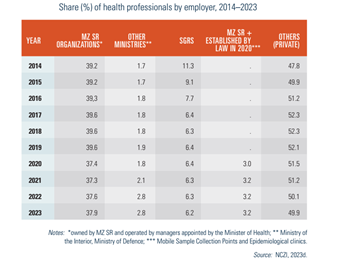

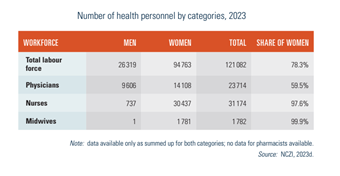

As of 2023, 121 082 people were employed in the health sector, representing 4.6% of the Slovak workforce. Roughly half (60 413) were working in the private sector, marking a rise in the share of private sector workers since 2014 (see Table4.7).

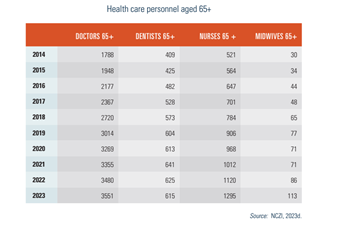

Table4.7

Ageing of the workforce is also a concern in Slovakia. There were 3551 doctors older than 65 years of age in 2023, representing almost 17% of all doctors (see Table4.8). Table4.9 shows that the health workforce in Slovakia is dominated by women, accounting for 78.3% of all health care employees; nurses are almost exclusively women (97.6%). Midwives are 99.9% female, while 59.5% of physicians and dentists are women (NCZI, 2023d).

| Table4.8 | Table4.9 |

|  |

9. Note that Netherlands (Kingdom of the) comprises six overseas countries and territories and the European mainland area. As data for this review refers only to the latter, the review refers to it as the Netherlands throughout. ↰

4.2.3. Professional mobility of health workers

high emigration rate of doctors, many leaving to work in economically stronger countries. According to the OECD (2024a), almost 15% of Slovak-born doctors and more than 25% of Slovak-trained doctors leave to work in other OECD countries. Most doctors trained in Slovakia went to Czechia (2218 doctors), Germany (1062), Norway (406) and Greece (193).This dynamic is even more pronounced with nurses, and surveys indicate that younger nurses with less work experience are more likely to leave Slovakia (Poliaková et al., 2022).An analysis on the outlook of doctors and nurses up to 2030 formulated two main conclusions (Bárta, 2023).

- Despite an increase in the number of doctors, demographic changes will cause the average medical doctor to have a heavier workload by 2030.

- The situation for nurses will exacerbate, as their numbers are projected to decrease. As a result, the decline in health care accessibility is likely to be even more significant.

Proposed strategies to head off these challenges include deregulating the health sector to draw in foreign doctors, adjusting the balance of international and Slovak medical students, and potentially boosting the number of medical students. Improving the retention rate of health professionals would also help (some reports suggest that only 40% of nursing graduates enter the profession), including enhancing the appeal of health professions, for example by increasing salaries, supporting work–life balance and providing opportunities for further education (Bárta, 2023).

Similarly, the Council for Budget Responsibility (Rada pre Rozpočtovú Zodpovednosť) found the modest growth in doctors in recent years is insufficient to maintain the current level of care for the ageing population (RRZ, 2023). Achieving this will require a long-term increase in the number of doctors by 4% compared to the current trend, which can be achieved through changes in the policies of medical faculties. The current practice has resulted in medical faculties admitting up to 40% of foreign students (see Section 4.2.4).

4.2.4. Training of health personnel

Professional qualifications can be obtained from universities, colleges or high schools, and this can be done through higher education of the first or second degree, higher vocational education, full secondary vocational education or secondary vocational education. Physicians are educated in one of three universities (Comenius University and the Slovak Medical University in Bratislava or PJ Safarik University in Košice) among four faculties that provide accredited study programmes in general medicine and dentistry.

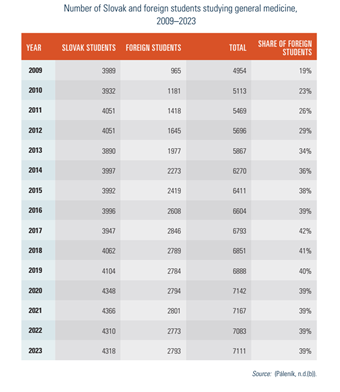

Study programmes are comparable to those in other EU countries and are carried out in accordance with Directive 2005/36/EC (the recognition of professional qualifications). The number of medical students is limited predominantly by the capacities of the universities. There are around 4300 Slovak students studying general medicine annually. On the other hand, the number of foreign students has been rising rapidly. In 2009 the share of foreign students was around 19%; in 2023 it was 39%, meaning 2800 foreign students, who study general medicine (in English) (see Table4.10). The reason for the rise of English-speaking foreign students is predominantly financial. Universities obtain €7000–€7500 annually for a Slovak student from the state budget (Struhárňanská, 2023), while they charge €9000–€11 900 annually for foreign students that are usually recruited via specialized agencies.

Table4.10

A medical degree programme usually lasts for six years and is divided into two parts.

- Preclinical Years: The first three years focus on basic sciences like anatomy, physiology, biochemistry and pathology. Students learn about the structure and functions of the human body.

- Clinical Years: Students rotate through different specialties, gaining practical experience under the supervision of experienced physicians. They learn how to diagnose and treat patients, as well as developing skills in communication and teamwork.

Pharmacists complete a five-year master’s programme (Title “Mgr.”), which consists of at least four years of theoretical and practical teaching at a university and at least six months of experience in a public or hospital pharmacy. Graduates of the pharmaceutical programme may also choose a doctorate programme.

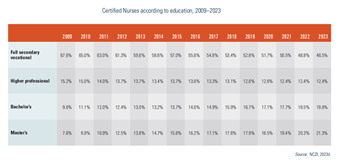

Nurses are differentiated by education level: bachelor or master, practical nurse (assistant) and certified nurse (see Table4.11). The role of practical nurse (assistant) is distinct from the profession of certified nurse and they have varying education requirements. When students complete their four-year studies with a high school diploma (“full secondary vocational” education), this qualifies them for the position of medical assistant (practical nurse). They can continue to university, where after a three-year study course they will receive a bachelor’s degree, or later a master’s degree (nurse). As an alternative, candidates can continue their higher professional studies at a technical institution (as an alternative to the bachelor study) and in three years they will become a certified nurse (Gdovinová, 2018).

Table4.11

To perform the professional work activities of a nurse, candidates are required to obtain higher education in the field of nursing (MZ SR, 2011a). Nurses receive an academic bachelor’s degree comparable to those in other EU countries and the professional title of Nurse. Graduates can pursue a master’s degree. Another possibility is higher professional education in the “certified general nurse” field of study. To perform the professional work activities of a practical nurse, candidates are required to obtain a complete secondary professional education in the “practical nurse” field of study (MZ SR, 2011b). Midwifery is taught in accordance with Directive 2005/36/EC.

Each health professional is obliged to register in the relevant professional chamber and regularly update their occupational and educational activities. Health care professionals can be providers themselves (as business owners) or employees of a provider. As providers they need both a permit and a licence, but as employees they need only a registration from the professional chamber. A licence is also issued by the professional chamber and provides proof of qualification (education and years of practice).

Subsequently, health workers can specialize in the system of further education or be certified and obtain professional competence for the performance of specialized and certified work activities. Further education of health care workers is provided by:

- specialization studies (also called attestation);

- certification training; and

- continuous education.

Continuous education for health workers of the relevant health profession is provided by the employer, professional societies of the Slovak Medical Association and the chamber in which the health worker is registered, independently or in cooperation with educational institutions or other internationally recognized professional societies or professional associations and providers. Educational evaluation is carried out in regular five-year cycles (Zákony pre ľudí, 2019).

While the Ministry of Education oversees general educational standards, MZ SR is typically involved in setting standards specific to health care professions. This can include requirements for medical schools, nursing programmes and other health care-related educational institutions.

Accreditation of specialized and certification education, continuous education, first aid courses and first aid instructor courses for health workers is dealt with by the Accreditation Commission of MZ SR for further education of health professionals, which is an advisory body in matters of further education of health workers. Minimum standards for programmes are set by MZ SR.

4.2.5. Physicians’ career path

Professional development for doctors depends on individual motivation and ambition, which leads to variations in possible nationwide career paths.

- Doctors can stay without further specialization and work in a hospital with limited scope of practice.

- Doctors can obtain a specialization in one of the specialty fields acknowledged by the EU (for example, surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology) and practise across all EU Member States without limitation on their scope of specialization. Certain requirements exist for each specialization in terms of length of training, rotations and numbers of procedures performed.

- In hospitals, doctors can progress from senior physician to assistant medical director and medical director. In university hospitals doctors may combine clinical duties with research activities.

- Doctors can obtain a licence that enables them to provide medical services as sole proprietor or become sponsors of another entity that provides medical guarantees for provision of care.

- Doctors can pursue research and conduct pure biomedical research or focus on lecturing at one of the medical universities while receiving a PhD degree.

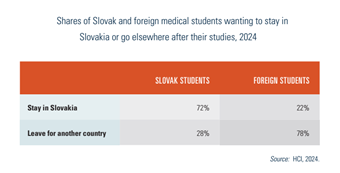

However, survey data from 2024 show that more than one quarter of medical students want to leave Slovakia after finishing their studies (see Table4.12).

Table4.12

A specific residency programme was introduced to secure a sufficient number of physicians in the specializations of general medicine and paediatrics across Slovakia and to support their further education (MZ SR, 2011c). The residency programme started as a pilot project in the academic year 2014/2015 at three universities across the country. Since then it has continued and graduates of medical faculties can enrol in either of these specialization fields upon completion of their medical studies. After completion of the residency programme, students are obligated to provide health care in a general outpatient clinic for adults or in a general outpatient clinic for children and adolescents. After the initial five years of the pilot, and costs of €22.2 million, the NKÚ identified a number of shortcomings, such as frequently changing conditions, restrictions in the form of sanctions, curtailment of maternity and parental leave, the requirement to stay in a specific region and missing evaluations (NKÚ, 2020).

4.2.6. Other health workers’ career paths

Dentists

Given the potential for high earnings, the dental profession has become very attractive among students over the last 10 years (see Table4.13). Data from Profesia.sk (n.d.), the biggest HR portal in Slovakia, show that the monthly gross salary (in 2023) of a dentist is around €5000 (roughly four times the average Slovak salary of €1304).

Table4.13

After finishing university, dentists do not need to pass a specialization exam and they usually begin to practise just after graduation as employees before opening their own clinics. This requires a permit, and is first based on the decision of the Slovak Chamber of Dentists on the issuance of a licence. This licence is tied directly to the commercial entity that will operate the clinic. The licence is officially issued by the Slovak Chamber of Dentists and an applying dentist needs to submit (1) verified diplomas and certificates, (2) a health certificate from a GP, (3) a criminal background check not older than three months and (4) their record of previous experience and practice.

A hygiene certificate is also required from the Regional Public Health Authority (as for other providers), which certifies that the operating procedures of the clinic meet all criteria regarding material and personnel. The dentist may then submit a request for a permit to their SGR to open the clinic (or to MZ SR if applying for offices across multiple regions), providing business operating hours and a price list. There is no guarantee that new dental clinics will obtain contracts with HICs right away, and usually new clinics start taking OOP payments first.

According to Igor Moravčík (Štenclová, 2019), the president of the Slovak Chamber of Dentists, an issue in Slovakia is dentists’ non-proportional geographical distribution (the national average is 55 per 100 000 inhabitants). This is confirmed by analysis from 2022 which found that in Bratislava there were 81 dentists per 100 000 inhabitants, but only 41 per 100 000 inhabitants in the Nitra Region, followed by Banská Bystrica with 44 and Prešov with 48 (Páleník, 2022).

Pharmacists

Pharmacists can decide to pursue a career in the pharmaceutical sector or choose to work for or run a pharmacy. The criteria and the process to open a pharmacy include the following (Podnikatelsko.sk, 2024).

- Establish a limited liability company (other options are also possible, but this is the most common).

- Obtain a type C licence. This requires second-level university education in the field of pharmacy and professional experience of at least five years in a public pharmacy or a hospital pharmacy, or a specialization in the specialized field of pharmacy.

- Obtain a permit to operate a public pharmacy. This permit is issued by the relevant SGR, according to the intended place of operation of the pharmacy.

- Entry of the permit in the commercial register.

Nurses

Unlike doctors, there is no binding nationwide career path for other health workers. Nurses can work in a hospital and progress to different specializations and levels of patient responsibility. Furthermore, nurses can choose to work in ambulatory settings or obtain a licence to provide either nursing services as a sole proprietor or run a nursing home and nursing care services. Other health care professionals, such as hospital auxiliary staff, do not follow a defined career path either.

4.2.7. Outlook

Slovakia’s approach to its health workforce necessitates the implementation of modern human resource management strategies, their organization, substitution, or on-site and online compensation. If Slovakia hopes to maintain or try to increase health workforce, current class cohort sizes, and their flexibility in choosing specialties, are concerns to address. Greater recruitment of foreign professionals may also help, particularly to support the return of Slovak professionals who have previously left to work elsewhere.

Achieving greater productivity and value for patients with existing or fewer physicians requires attention to strengthen primary care, with a modern type of GP that is clinically, technically and managerially skilled. Here, new curricula during the training of the next generation of GPs can impart these skills. Strengthening the function and competence of nurses and other workers can also further aid the transition from reliance on specialists and hospitals to primary care, as many hospitalizations can be avoided if primary care is strengthened (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2023). Support staff, as well as the implementation of new technologies (digitization, AI) are also critical to pursuing new ways of organizing health services. Regions with a higher degree of fragmentation of health services rely to a greater extent on more intensive contact with specialists and less use of primary care. They also have higher numbers of hospitalizations, emergency room visits and repeated use of imaging and diagnostic methods (Agha, Frandsen & Rebitzer, 2019). Reducing the level of fragmentation of the Slovak health system thus appears to be one of the key strategies for compensating for the future shortage of human resources. The government has also launched a support scheme incentivizing the return of specialists from abroad (Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic, n.d.(c)).