-

15 August 2025 | Policy Analysis

Out-of-pocket payments in Slovakia reach EUR 1.7 billion with very low transparency and high legal uncertainty

3.4. Out of pocket payments

OOP payments in Slovakia mainly consist of (1) co-payments for prescribed pharmaceuticals and medical goods; (2) user fees for various health services, dental care and spa treatment; (3) direct payments for OTC pharmaceuticals, vision products and dietetic food; (4) above-standard care, preferential treatment and care not covered by social health insurance; and (5) a few standard fees – for 24/7 first aid medical services (€2), ambulance transport (€0.1/km), for accompanying people during a hospital stay (€3.3), as well as for food and accommodation in spas (€1.7–€7.30 per day).

Slovakia supports underprivileged residents in the form of maximum limits for co-payments for prescribed pharmaceuticals, waiving ambulance transport fees for the chronically ill, and a wide range of medical devices with individually reduced cost-sharing. The system of maximum limits for co-payments for prescribed drugs was expanded in 2021 to include pensioners, provided that their net income is below a certain quarterly set threshold. The limit is currently set into three groups, with €0, €12 or €30 maximum co-payments per quarter, depending on fulfilled conditions and the category of a person. In 2023 the cost of covering these co-payments was €73.8 million, aiding 1.4 million insurees in Slovakia. This represents a significant increase compared to 2020, when the cost of covering the co-payments was only €24.5 million, aiding 1 million insurees (ÚDZS, 2021c, 2024c).

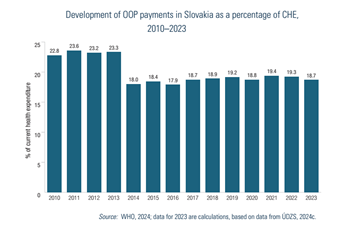

Fig3.7 illustrates the level of OOP payments over time in Slovakia. Declines seen in the early 2010s were caused by methodological changes by ŠÚ SR in 2011 and 2013.

Fig3.7

It is important to also note that despite methodological changes and improvements, the provided OOP expenditure is based on estimations. The methodology of ŠÚ SR for calculating OOP payments also includes, besides co-payments for prescribed drugs, items that are sold in pharmacies but are only marginally health-related, such as cosmetics. However, due to the technical limitations of reporting receipts to the Ministry of Finance, these items cannot be always split from pharmaceutical expenditures. This may overestimate OOP payments in Slovakia. On the other hand, OOP payments may be underreported given the weak reporting legislation for non-standard services, which include, for example, different administrative fees and specialists’ examinations without referral from GPs.

In 2023, total out-of-pocket spending (OOP) in Slovakia reached EUR 1.7 billion EUR, and just over 18% of current heealth expenditure. At the same time, OOP payments are legally inconsistent, economically inequitable and lack transparency (see Table 1). Analysis of OOP spending reveals several key issues:

Low transparency and information asymmetries

Patients often do not know what exactly they are entitled to, do not understand the differences between a fee and a co-payment, or betweenstandard and above-standard service. Patients are often not informed by providers of these differences. Patients are often not issued receipts in practice, further reducing transparency.

There is also a variation in patients‘ readiness to pay, with some unwilling or unable to do so. Some are unwilling based on the principle of free healthcare at the point of service, while others, especially in poor regions, simply cannot afford to pay. There are also those willing to pay OOP, giving them priority and more adequate consultation times, scheduled appointments, and an individual, higher-quality approach.

Gaps in regulation, inconsistent approaches and legal uncertainties

There legal uncertainty surrounding the interpretation regarding providers’ ability to charge fees. After approximately 600 amendments since their adoption, laws 576, 577, and 578 of 2004 (core laws underpinning the major 2004 health system reform) create contradictory motivations for providers.

As stated by providers, a main reason for rising fees is due to insufficient reimbursements from insurers, leading them to seek alternative sources of funding to try to maintain levels of care quality. Other given reasons include rising staff wages (especially in public hospitals), the introduction of a transaction tax, general inflation across the economy and increasing energy costs.

Beginning in 2006, legal restrictions against direct payments were introduced. However, in practice, a chaotic “fee jungle” has emerged, with exploitation of numerous legal loopholes. This is also reflected in the varying levels of patient information (differing communication and price list publication methods), reducing predictability of patient costs.

Furthermore, the absence of regulation has led to variability in the fees charged among providers even within the same specialty. Price lists reveal regional differences: the highest charges are in Bratislava (sometimes multiple times higher), while in smaller towns or rural areas, fees tend to be lower or nonexistent.

Finally, an outdated performance catalogue does not reflect technological progress nor current market prices for materials. Notably, the catalogue was originally intended as a tool for introducing innovation (for example, telemedicine, AI, interventional radiology), not solely as a pricing mechanism.

Table 1: Legislative anchoring of direct payments and their relationship to public health insurance

| Occurrence of direct payment | Purpose of direct payment | Legislative basis |

| Before provision | Patient management | Act 576/2004 allows for charging for services beyond standard public coverage. However, annual care program services may be covert payments for services that should be free (Act 577/2004 prohibits fees for appointment scheduling, priority treatment, and administrative tasks). There are often collected by intermediaries (not the providers themselves); the healthcare service itself is reimbursed by an insurer. |

| Reservation portal | Legal loophole: current laws prohibit providers from charging for scheduled appointments.

Exploited by third-party private companies offering booking systems independent from the state and healthcare providers. |

|

| During provision | Fees for services related to care provision. | Regulated in §38 of Act 577/2004 in which Slovakia’s Constitutional Court confirmed that such charges are constitutional. |

| Co-payments for medicines, medical aids, durables and materials and dietetic food | Yes, most clearly regulated type.

Defined entitlements and transparent costs for both insurer and patient. |

|

| Direct payments to non- contracted providers | Governed by commercial code | |

| Price list fees | Partially regulated: not clearly defined in Act 577/2004 and indirectly referenced in Act 578/2004 requiring a public price list submitted to regional authorities Legally questionable in some cases (e.g., booking fees, prescription printing, spa referral), and often charged due to outdated reimbursement catalogue or lack of coverage in practice. | |

| After provision | Second opinion | While not explicitly defined in law or reimbursement systems, this is usually billed to insurers as a regular consultation or repeat exam. Sometimes charged separately, especially for advisory consultations. |

Source: Pažitný et al. 2025

An examination of the health financing in Slovakia’s specialized outpatient care sector reveals a fragmented landscape of patient cost sharing and direct payments. Legal ambiguity, regulatory inconsistency and increasing financial burdens for patients create significant challenges for fairness, transparency and sustainability. Key areas for reform, not only to simplify rules and protect patients but also to restore trust and ensure long-term sustainability of the health system could include the following:

- Legalizing all types of co-payments – being clearly defined in Act 577/2004 and making any fees and co-payments transparent and understandable.

- Extend informed consent – informing patients of the amount in advance and for what service they are paying.

- Issue receipts for every healthcare service provided – an invoice showing exactly what services were provided, and what is paid by the insurer and what by the patient.

- Health insurers must be involved – informing insurers about any patient charges collected by providers.

- Introduce effective financial protection via co-payment limits – with eligible populations clearly defined.

- Shift the control of patient charges to regional authorities – via legislation to allow them to define scope and amount of allowed fees locally.

- Creation of a reimbursement mechanism to help cover some administrative costs – with the involvement of the Slovak Social Insurance Agency, health insurers and providers

Authors

References

Pažitný, Kandilaki, Macko-Forgáčová, Löffler, Zajac: Direct Payments in Specialist Outpatient Care in Slovakia, June 2025

Smatana, M. et al. (2025) in press. Slovakia: health system review 2024. Health Systems in Transition

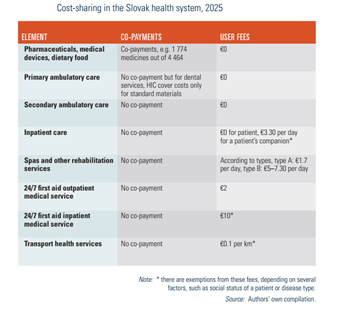

3.4.1. Cost-sharing (user charges)

Table3.8 outlines the cost-sharing framework in Slovakia. A variety of policies have been adopted to contain the increase in cost-sharing, such as the de facto abolishment[6] of co-payments for outpatient care and hospital stays in 2006 or lowering co-payments for prescribed medicines. Nonetheless, the proportion remains high, since most OTC drugs are not regulated and a small number of services (for example, dental care or ophthalmology care) still incur cost-sharing, along with some anchored fees for emergency services, ambulance transportation and spa treatment.

Table3.8

- 6. Co-payments have never been abolished in practice; legally, their value was set in legislation to zero. ↰

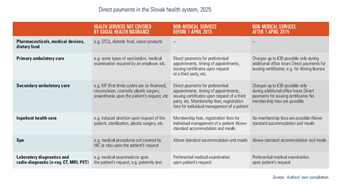

3.4.2. Direct payments

Direct payments comprise mainly payments for OTC pharmaceuticals and dietetic food and care not covered by social health insurance.

In 2015 MZ SR introduced new legislation restraining possibilities for providers to charge for health care and health-related services. This was a response to the fact that although cost-sharing for medical services was regulated gradually, the providers were free to charge fees related to care (such as payment for air conditioning in the waiting room, payment for administrative tasks, payment for printed documents, etc.). These payments were identified as one of the key drivers of increasing OOP expenditure but were virtually outside legislative control. The new legislation since 2015 defined which non-medical services can be charged for and enforced greater control by the SGRs. MZ SR in 2019 introduced another amendment to the legislation that enabled providers to charge a fee for an examination during so-called “additional office hours” with a maximum ceiling of €30 per treatment, providing that:

- the range of additional office hours may not exceed 30% of the approved office hours in a calendar week;

- the number of people examined during additional office hours must not exceed 30% of the total number of people examined in the previous calendar month; and

- additional office hours can be after 13:00 at the earliest.

A brief overview of some direct payments is given in Table3.9. Despite these changes, providers still tend to request direct payments for services. There is a grey zone in legislation that enables providers to ask for payments, but on a voluntary basis. Patients are, however, often not aware that such requested fees are a voluntary donation and end up paying directly to the provider. This practice culminated during January 2023 since many outpatient providers did not have sufficient reserves to catch up with rising energy prices and inflation and had to ask patients to voluntarily pay extra for services (Madro, 2023; Surová, 2019).

Table3.9

3.4.3. Informal payments

According to a Eurobarometer survey, 9% of Slovaks admitted to paying bribes and donations in the health care sector in 2022, the highest among the Visegrad 4 (V4) countries (Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia). This is the third highest value in the EU, after Romania and Greece (Eurobarometer, 2023). Moreover, this percentage seems to be growing, as only 4% of Slovaks admitted to any kind of informal payment to a doctor or a nurse in 2017 (Eurobarometer, 2017). The total value of such payments is, however, not known and thus difficult to estimate. See Section 7.1.1 for more information.