-

22 July 2024 | Country Update

Political interference in the Slovak health system

7.1. Health system governance

MZ SR sets strategies and implements reforms, currently through the Strategic Framework for Health 2014–2030. Created in 2013 and significantly updated in 2022, it defines medium- and long-term health policy in Slovakia (MZ SR, 2023i). It also identifies a set of indicators to be measured and evaluated. However, this was primarily developed to access EU funding and has not been used in practice; there is no systematic monitoring to ensure up-to-date information about the policies’ impact on health system goals. There is little formal stakeholder involvement, with limited impact on accountability. Nevertheless, public participation in the Slovak health system is reflected in the large number of patient organizations (which have AOPP as their umbrella organization; see Section 2.2.4). Representative organizations and associations have an opportunity to comment on new legislation but are limited to only voicing recommendations. They also advocate their interests by lobbying legislators and by courting public opinion.

In practice, policy development and governance have largely been guided by the incumbent government’s or health minister’s policy statements or priorities. As the average ministerial tenure since 1993 is approximately 20 months, initiatives with medium- to long-term impact are rarely implemented (MZ SR, 2023j). Furthermore, an analysis of strategic health policy documents by NKÚ found that MZ SR does not have a system of evidence or strategy evaluation in the health sector, and that most strategic documents from MZ SR lack sufficient descriptions of financing or implementation monitoring (NKÚ, 2022).

Given long-term underfinancing and the regular top-ups that HICs receive, the Ministry of Finance has taken a strong role in health system governance. This has increased considerably since 2016, with the first HSR. Written by the analytical units of the Ministries of Health and of Finance, the HSR detailed where to improve technical and allocative efficiency in the health system via savings (Ministry of Finance, 2016a). This was subsequently updated in 2018, 2019 (Ministry of Finance, 2019) and 2022 (Ministry of Finance, 2023), and gradually morphed from a document describing savings to one also focusing on where the state should invest and increase social health insurance funding to improve overall care quality and/or accessibility (Ministry of Finance, 2023). The HSR has thus become a key document linking policy and investments to the budgeting process, and has led to the establishment of an Implementation Unit in the Cabinet Office. The latest HSR, published in March 2025 (Ministry of Finance, 2025), is not focused on the entire sector: instead, it provides an in-depth overview of the efficiency of state hospitals. Future HSRs are planned to be thematic as a way to increase their applicability in practice.

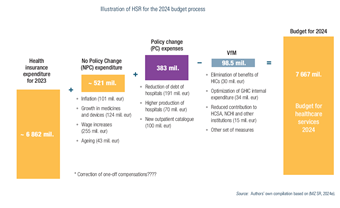

Budget preparation changed significantly in 2017, when the analytical units of the Ministries of Health and of Finance began preparing exact calculations of expected health system costs (previously, the state budget neither determined nor justified resources needed for the upcoming year). This is done by adding: 1) the expected expenditure of the current year, based on the HICs’ reports; 2) expenses deemed unavoidable (such as inflation, wages and ageing), also known as the no-policy-change scenario; and 3) the policy-change scenario, consisting of the expected new expenditure associated with reforms. Then the (value for money) savings based on the approved HSR are subtracted and the result is the expected health expenditure for the following year (see Fig7.1).

Fig7.1

Given the financing change in 2020, and that payments for state insurees were set as the residual of the expected expenditure and the expected collection of contributions from the economically active population, the HSR has thus become an integral part of defining the health budget. Even though at the time of writing, the contribution for state insurees was once again a fixed percentage of the average wage, the process of budgeting remains unchanged and MZ SR must take heed of the HSR. If HSR actions are not implemented, there is a theoretical budget deficit. In practice, even stringent austerity measures achieve only up to 70% of identified savings and the continual losses by the HICs necessitate regular funding infusions (Implementation Unit, 2022; ÚDZS, 2023c).

Compliance with non-fiscal measures from the HSR is also monitored by the Implementation Unit of the Cabinet Office, which transforms HSRs into so-called Implementation Plans. Each Plan is prepared jointly with relevant ministries, contains a detailed timetable and responsibilities, and its approval is subject to standard lawmaking processes. Thus, HSRs have become the dominant instrument influencing health system governance and the distribution of responsibilities.

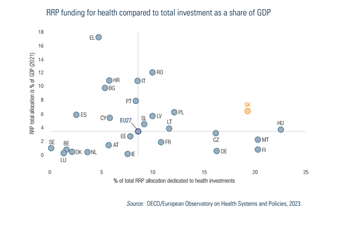

In 2021 the approved RRP entered the health system governance process, the conclusions of which were reflected in both the Strategic Framework and in the updated HSR in summer 2022. The primary difference between them is that the HSR focuses on social health insurance spending and the internal cost-efficiency of MZ SR and state-owned hospitals, and implementation largely does not require legislative changes. The RRP discusses capital spending and defines the reforms that MZ SR must implement if it is to receive the promised funds. As health was a main priority of the RRP (see Fig7.2), this document shapes the design and implementation of policies and reforms.

Fig7.2

As explained in a previous policy analysis (https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/monitors/health-systems-monitor/analyses/hspm/slovakia-2016/slovakia-s-health-care-surveillance-authority-s-lacking-institutional-stability-and-independence), the Health Care Surveillance Authority (Úrad pre dohľad nad zdravotnou starostlivosťou in Slovak) plays an important regulatory role in the Slovak health system and is responsible for supervising health insurance, purchasing and healthcare markets. As with previous governments (no chair of the Health Care Surveillance Authority has served a full term since its establishment in 2004), the current government led by Prime Minister Robert Fico with Minister of Heath Zuzana Dolinková have politicized the role of the Authority’s chair. In February 2024, they used legislative amendments to §22 of Act 581/2004 to remove the then-incumbent Renáta Blahová.1, 2

More recently, the Fico government has adopted legislation to take effect on 1 August 2024 to change the criteria of who can serve as director of the National Institute for Value and Technologies in Healthcare (NIHO or Národný inštitút pre hodnotu a technológie v zdravotníctve), which was established in 2022 and is responsible for Health Technology Assessment in Slovakia. The new criteria specify that only a doctor or pharmacist could serve as head of the HTA agency (leading to the dismissal of the current head, Michal Staňák); the legislation also enables the Minister of Heath to dismiss the agency’s director at any time and without cause.

Besides the political sphere pushing itself into the decision-making levels of these two seemingly independent organizations within the health system, the current government has also used their existing authority to make the following changes in healthcare institutions and providers around the country since coming into office in October 2023 (the dates refer to when the officials were dismissed or replaced):

- Tomáš Janík, director of Faculty Hospital Trenčín, 14 November 2023.3

- Vladislav Šrojta, director of Faculty Hospital Trnava, 30 November 2023.4

- Pavol Bartošík, general director of Central Slovak Institute of Heart and Vascular Diseases (Stredoslovenský ústav srdcových a cievnych chorôb), 5 December 2023.5

- Ľubomír Šarník, director of Faculty Hospital Prešov, 6 December 2023.6

- Jozef Tekáč, director of Faculty Hospital Poprad, December 2023.7

- Eduard Dorčík, director of the hospital in Žilina, December 2023.8

- Peter Potůček, director of State Institute for Drug Control (Štátny ústav pre kontrolu liečiv), 31 December 2023.9

- Ľubica Hlinková, general director of VšZP (Všeobecná zdravotná poisťovňa), the state-owned Health Insurance Company, 10 January 2024.10

- Peter Lukáč, director of National Centre for Health Information (Národné centrum zdravotníckych informácií), 10 January 2024.11

- Ivan Kocan, director of University Hospital Martin, 10 January 2024.12

- Július Pavčo, director of Emergency Medical Service Operations Centre (Operačné stredisko záchrannej zdravotnej služby), 31 January 2024.13

- Renáta Blahová, Chair of Health Care Surveillance Authority, 6 February 2024.14

- Michal Fajin, director of Faculty Hospital Nitra, 14 February 2024.15

- Matej Mišík, chief of the Institute for Healthcare Analyses (Inštitút zdravotných analýz) at the Ministry of Health was revoked on 20.6.2024 without any reason. The Institute focuses on: epidemiological studies and data analysis, sector analysis and health policies, implementation of optimization of the hospital network and the development of the DRG reimbursement mechanism.16

- Michal Staňák, director of NIHO, according to legislation set to take effect on 1 August 2024, enabling the Minister of Health to dismiss the NIHO at any time and without giving a reason. The Ministry of Health has already published the announcement for the selection procedure for the position of the new director.17

Authors

References

1. https://spectator.sme.sk/c/23346445/slovak-health-minister-direct-power-independent-body.html

5. https://www.health.gov.sk/Clanok?mz-suscch-vedenie-nove

6. https://domov.sme.sk/c/23281567/fajin-nemocnica-nitra-dolinkova-pellegrini-hlas-rozhovor.html

7. https://domov.sme.sk/c/23272033/zuzana-dolinkova-zdravotnictvo-nemocnice-cistky.html

8. https://dennikn.sk/minuta/3744432

11. https://zive.aktuality.sk/clanok/SdYXsqi/odvolali-riaditela-nczi-kto-bude-na-cele

13. https://www.health.gov.sk/Clanok?operacne-zachranka-riaditel

14. https://www.tyzden.sk/zdravotnictvo/106251/vlada-odvolala-sefku-udzs-na-jej-miesto-zasadne-palkovic

15. https://domov.sme.sk/c/23281567/fajin-nemocnica-nitra-dolinkova-pellegrini-hlas-rozhovor.html

7.1.1. Transparency

The overall perception of corruption in Slovakia has been gradually improving. According to Transparency International surveys, the share of cases in which some form of bribery occurred in the public sphere fell from 40.3% in 1999 to 10.2% in 2022 (Transparency International, 2023).

Lack of health system transparency is primarily associated with wasteful procurement. Following the 2016 parliamentary elections in which non-transparent tenders were a key issue, changes were introduced to improve both procedures and outcomes. These included mandatory price referencing of state hospital purchases, public disclosure of purchases and central procurement of expensive medical equipment. Many of these were temporarily suspended during 2020–2023 to speed up procurement during the COVID-19 pandemic, however. Perceptions of the presence of corruption in the health system stood at 58% in 2022 according to Eurobarometer, below only Greece and Lithuania among EU countries (Eurobarometer, 2022).

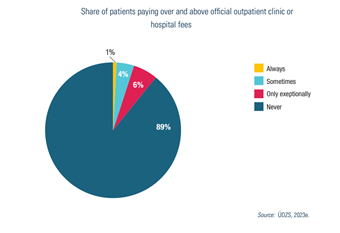

In theory, transparency regarding health benefits should be mediated by the broad and standardized benefits package and near universal population coverage. According to Eurobarometer, though, 9% of all doctor visits in 2022 resulted in some form of informal payment or gift over and above the official fees. This increased from 5% in 2019 and was the highest percentage in the EU after Romania (18%) and Greece (13%). Similar figures were found by a ÚDZS survey in summer 2023: up to 11% of patients reported that they had paid more than official fees for care (see Fig7.3) (ÚDZS, 2023e).

Fig7.3

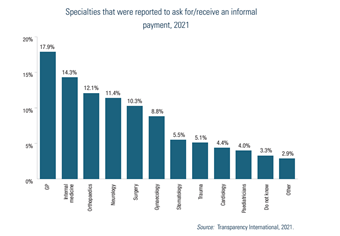

The distribution, amount and motivations of informal payments vary. According to a Transparency International survey (Transparency International, 2021), the majority are made to primary care physicians, potentially due to their significant shortage. A breakdown of specialties in which informal payments were most likely to be solicited is shown in Fig7.4.

Fig7.4

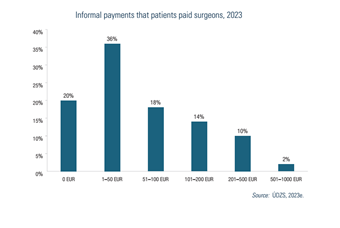

The survey also focused on the activities in which informal payments are most frequent. Their conclusion was that up to nearly 80% of all patients who underwent surgery made an informal payment to a doctor or nurse (that is, outside the official price list). The average amount of such payments reached, according to ÚDZS (2023e), as high as €115 in 2023; specific breakdowns are shown in Fig7.5. These payments do not enter official statistics on health spending, however, and reasons for these payments also vary. According to Eurobarometer (2022), up to a quarter of all informal payments were given to obtain better or earlier care for the patient.

Fig7.5