-

05 October 2021 | Policy Analysis

Trends and disparities in mortality and excess mortality due to COVID-19 and beyond -

30 September 2021 | Country Update

Final report of the Assessment of EPHOs with WHO Europe published -

01 March 2020 | Country Update

Chronic care nurses transferred to other postings in COVID-19 response

5.1. Public health

Institutional public health is organized mainly through two institutions: the NIJZ and the NLZOH (see section 2.2).

Both organizations were established in their current form by changes in the Health Services Act (1992) in 2013 and enacted in 2014, though the NIJZ and its nine regional public health institutes have played an important role in the delivery of public health initiatives since the 1990s. At the time, the NIJZ’s scope of work was broadly defined, spanning research, education and postgraduate training functions. The NIJZ also oversaw seven independent, regional public health (reference) laboratories. The 2013 reform transformed the separate public health institutes into regional units of the central NIJZ and established the NLZOH as the central public health laboratory with seven regional units (corresponding to the previous seven regional reference laboratories). Only one is still under the NIJZ: for stool samples for the national colorectal cancer screening programme.

Today, the NIJZ has a similar role and terms of reference as most equivalent national public health institutes in Europe. Covering all 10 Essential Public Health Operations (EPHOs) of the WHO Regional Office for Europe, its activities fall under four main branches: social medicine; hygiene; communicable disease epidemiology; and environmental health. The NIJZ maintains several important national health statistics databases (see section 2.6) and hosts the Centre of Informatics in Health and the Centre for Healthcare System.

In the absence of an explicit national public health strategy, several legislative actions and legal documents underpin Slovenia’s public health approach (Box5.1). A range of interventions impact on different levels of the health care system; some programmes, for example, directly address determinants of health, while others focus on secondary prevention (see below). Generally, Slovenia’s health care system has a particular emphasis on public health and preventive interventions (see section 2.1). Primary care services are delivered mainly by CPHCs, but in close collaboration with independent primary care providers, including family medicine specialists, paediatricians, gynaecologists and community nurses, across 63 CPHCs that operate at 506 locations. CPHCs are meant to foster confidence between the respective populations and the primary care professionals and be the backbone of an efficient primary care system, providing a multidisciplinary range of health promotion, preventive, diagnostic, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care, and also implement public health interventions (see section 5.3).

Box5.1

Since 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic and its high fatality rates, mortality and excess mortality has received a lot of attention across countries. In retrospect, we can now say that mortality due to COVID-19 was extremely high in the second wave of the epidemic, which hit Slovenia in autumn of 2020. The first wave had low incidence and mortality rates, so the impact of the epidemic in spring 2020 was minimal. It is estimated that around 3900 people died due to and with COVID-19 in 2020 overall, mainly in autumn 2020. That is almost 20% of the average absolute mortality in a year. Excess mortality in November 2020 reached between 66% and100% above average levels (1). The curves for mortality for COVID-19 and excess mortality were quite close to each other, indicating that most excess mortality was probably due to COVID-19. The situation repeated to a much lesser degree late in 2021, when excess mortality exceeded the pre-COVID-19 levels by a maximum of 50% and where the impact of COVID-19 was still significant but not to the same degree as in 2020.

The Euromomo webpage analysing excess mortality in Europe shows a significant excess mortality for Slovenia in 2020 with the maximum z-value of 14.43 (2). Fatality rates for COVID-19 were higher in all age groups for males. Additionally, over 75% of the excess deaths in 2020 occurred in persons above the age of 75 (1). Such burden on the elderly was particularly felt in the nursing homes across the country, where staff shortages, partly from before and partly as a result of absences due to COVID-19, required additional staff to be transferred in from primary care. For the most part, patients from nursing homes with severe course of COVID-19 were moved to hospitals, thus significantly saturating the overall hospital capacity for critically ill patients in most regional hospitals. Lessons from this situation in 2020 were then used as a guidance in the autumn of 2021, when hospital capacity never reached critical level, even though it became relatively saturated by the end of the year.

All these developments caused a net drop in life expectancy for both genders in 2020 of 1 year, namely from 81.6 years in 2019 to 80.6 years in 2020 (3). In 2021, there are signs of life expectancy picking up again to 80.9 years.

Authors

References

- COVID-19 data for Slovenia: https://covid-19.sledilnik.org/en/stats

- EU Webpage on excess mortality: https://www.euromomo.eu/graphs-and-maps/#z-scores-by-country

- Eurostat data for 2020: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00205/default/table?lang=en

From 2017 to 2019, the Ministry of Health and the WHO Regional Office for Europe, together with the NIJZ and over 120 stakeholders and professionals in public health, the community, and other sectors, conducted a comprehensive self-assessment of the WHO Regional Office for Europe’s 10 Essential Public Health Operations (EPHOs) in Slovenia. The final report was published in September 2021, and is intended to support the development of a new national public health strategy. However, the strategy has not yet been developed as major questions around scope and the context and extent of additional financing required are still not answered. A national strategy on public health is necessary at this point, as is a strategy of the National Institute of Public Health.

Authors

References

EPHO self-assessment process in Slovenia (2017 – 2018) | European Journal of Public Health | Oxford Academic (oup.com): https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article/28/suppl_4/cky218.083/5192339

https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289055895

In the face of an ageing population and increasing (multiple) chronic diseases, Slovenia has worked to strengthen its management of chronic diseases and noncommunicable disease risk factors. In 2018, Family Medicine Practices were nationally scaled up to improve prevention and care coordination for patients with stable chronic diseases. The practices include a new staffing standard in primary care, particularly in the CPHCs, in the form of an additional 0.5 full-time equivalent of registered nursing support. Patients who visit a practice receive a consultation with a specially trained nurse who assesses their current lifestyle and screens for risk factors and provides regular advice and follow-up.

Due to the shortage of nursing staff across the health system, which was acutely felt during COVID-19, most of the nurses employed in Family Medicine Practices were re-deployed to nursing homes, some hospital departments (if they had previous hospital experience), vaccination points and to perform COVID-19 testing to bolster the frontline response to the virus. This undermined the health system’s key tactic for managing and reducing chronic diseases, weakened primary care’s community-oriented working methods, and, for the nurses, represented a worsening of working conditions as the hours required of them in these seconded posts were much more than in their usual jobs. Previously well-managed preventative programs for chronic care were effectively stopped.

Authors

References

- Emergency instruction of the Ministry of Health to Primary Health Centres from 25 October 2020 – instruction on the possibility of repositioning nurses to other posts within the PHCs and to other providers.

- Order of the MoH on the temporary measures to contain the epidemic of COVID-19 enacted in a legal act adopted on 13 November 2020.

- Order of the MoH on the temporary measures to contain the epidemic of COVID-19 enacted in a legal act adopted on 15 November 2021.

- Explanation on provision of preventative health programs during the times of the epidemic of COVID-19, issued by the MoH on 20 October 2020

5.1.1. Surveillance and control of communicable diseases

The NIJZ is responsible for surveillance of communicable diseases, with the NLZOH as its main diagnostic and microbiological partner. The Institute of Microbiology at the Medical Faculty in Ljubljana also carries out laboratory testing for various infectious diseases and is the reference laboratory for haemorrhagic fevers.

The NIJZ maintains the annual immunization programme. It manages the central storage facility for all vaccines, including purchasing and stockpiling and oversees distribution of vaccines across Slovenia from its central storage facility in Ljubljana. This has also been the case during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.1.2. Immunization

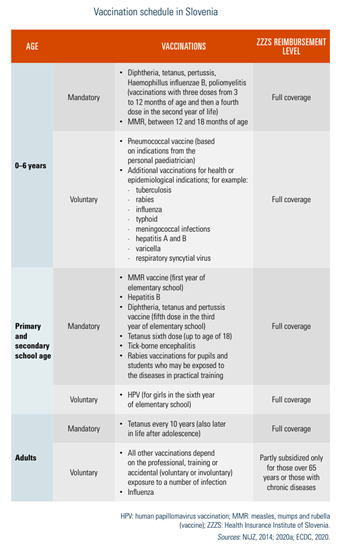

Slovenia’s immunization programme is extensive. The National Immunization Programme and the Calendar of Vaccinations are prepared and updated annually by the NIJZ. Children and students up to 26 years old receive free services, but the ZZZS reimbursement varies for adults. Paediatricians are fully responsible for providing vaccinations to children aged 0–19 years; family medicine specialists are responsible thereafter.

Table5.1 outlines the schedule for mandatory and non-mandatory vaccinations by age and reimbursement level.

Table5.1

Population coverage for the basic vaccinations in the first year of life was around 94–95% for the past few years. In 2020, coverage was 94% of the target population for first and second doses of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR). The more recently introduced pneumococcal vaccine has seen rapidly enhanced coverage, from around 49% in 2015 to 70% in 2020; however, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage in girls is still only around 59% (from 48% in 2016–2017). In May 2021, it was decided that the vaccine would also be introduced to boys. Coverage for the hepatitis B vaccine, which is now universally administered to all school children, is consistently high at around 80%. There is increasing concern about vaccine hesitancy, mostly from parents worried about the side-effects of vaccinations. In 2015, Slovenia launched several vaccination promotion activities to mitigate this issue.

In addition to those vaccines listed, COVID-19 vaccines are available free of charge for the entire population from the age of 12 without restrictions, following the recognized vaccination schemes defined specifically by each producer. COVID-19 vaccination is carried out by the vaccination centres mainly organized by the CPHCs. According to the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC), the cumulative uptake of at least one vaccine dose among adults aged 18 years or older in Slovenia is 51.0% (as of 3 August 2021), below the EU/EEA average of 70.8% (ECDC, 2021).

5.1.3. Prevention and health promotion

Women often register with personal gynaecologists (also working as primary health care physicians) as well as family medicine physicians (see sections 5.2 and 5.3) and receive a variety of reproductive health services, including cervical cancer screening, family planning, and ante-and postnatal care.

Dentists in primary care provide both preventive and curative services for adults and children. Paediatric dentist services are fully reimbursed and providers are evenly distributed across the country (Johansen, West & Vracko, 2020) (see section 5.12).

The NIJZ and the MoH, as well as several other institutions, are involved in health promotion. Since 2013, NIJZ’s Centre for the Management of Prevention Programmes and Health Promotion is responsible for designing, preparing and monitoring national prevention and screening programmes for adults. The Centre governs the national coordination of health promotion programmes and collects data on the prevalence of chronic diseases and risk factors to ensure appropriate inputs into the planning of health promotion activities. Maternal, children and adolescent health promotion programmes are designed and coordinated at the Centre for Analysis and Development of Health. The goals of Slovenia’s public health approach are detailed in the National Plan on Nutrition and Physical Activity 2016–2025, along with an Action Plan for 2019–2022 (Box5.1).

Box5.1

In line with the community-based primary health care model in Slovenia, encompassing a range of preventive and curative care (see sections 2.1 and 5.3), health promotion and education programmes to address most of the common population health needs across individuals’ lifespans, close to where they live, are also implemented at the primary care level, primarily by nurses and other health care professionals working in the CPHCs. In addition, since the early 2000s, health education centres (HECs) work on health promotion (see section 5.3) in CPHCs. However, they are gradually being replaced by HPCs. HPCs were introduced in 2017 (see section 2.1) to enhance health promotion at the community level, especially for marginal and vulnerable groups. Starting with three pilots, there are now 28 centres across the country, staffed by registered nurses, physiotherapists, psychologists and dietitians. They link closely to the municipality, local communities and NGOs on different health promotion topics and offer a wide range of services supporting healthy lifestyle choices and advice to the healthy population.

The aim is to establish HPCs next to all CPHCs over the next three years. In addition, building on the Programme for early detection of depression and treatment (Box5.2), MHCs, staffed with registered nurses, psychologists and psychiatrists, will be launched in 2021 to connect HPCs to facilitated access to psychiatric and psychological care (see sections 6.1 and 7.6.1).

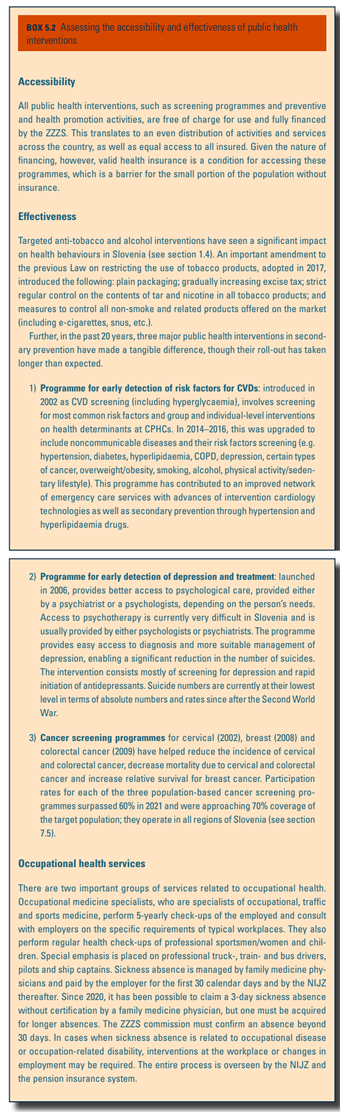

Box5.2

Since 2011, “family medicine model practices” have also been in place in some CPHCs to improve management of chronic diseases and noncommunicable disease risk factors (see section 5.3). Since 2018, these have been renamed Family Medicine Practices and have been stepwise introduced and become a standard for family medicine practice. They focus on prevention and care coordination for patients with stable chronic diseases, such as hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, diseases of the prostate and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), thus fulfilling a secondary and tertiary prevention mission (see sections 5.3 and 7.4). An additional 0.5 full-time equivalent of nursing support means that patients who visit a practice receive a consultation with a specially trained nurse who assesses their current lifestyle and screens for risk factors. Once part of the programme, the nurse then provides regular advice and follow-up (e.g. on weight loss, smoking cessation, alcohol cessation), and takes on and incorporates feedback from patients. In 2021, around 75% of all family medicine practices had adopted these services; it is expected that by 2023 all will have. Similar initiatives are now under way for primary care paediatrics and gynaecology, pending approval by the Health Council.

5.1.4. Screening programmes

Several national screening programmes have been launched since 2000, including for the early detection of cervical cancer (2002), risk factors for CVD (2002), breast cancer (2008) and colorectal cancer (2008) (Box5.2). The Institute of Oncology organizes the screening programmes for cervical and breast cancer; the NIJZ for colorectal cancer. CVD risk factor screening is conducted through the network of family medicine practices. Though not organized as systematic population screening, men over 50 are also offered prostate-specific antigen testing that is reimbursed by the ZZZS on demand from the primary care physicians who order the test.

Box5.2

Box5.2 provides information on the accessibility and effectiveness of public health interventions in Slovenia.