-

03 February 2023 | Policy Analysis

Family doctor shortages in primary care -

01 June 2022 | Policy Analysis

Entry points for the strategy for the development of primary health care 2022–2031 -

01 March 2020 | Country Update

Chronic care nurses transferred to other postings in COVID-19 response

4.2. Human resources

Shortages of family doctors in Slovenia have been present – to greater and lesser degrees – for the last ten years. This is due to several factors including a decline in the number of junior doctors entering this specialty, coupled with a process of retirements within an important and large cohort of current family doctors.

Family medicine is among four specialities, along with pediatrics, primary care level dentistry, pediatric dentistry and gynecology, of which specialists qualify as personal physicians in primary care. Further, as family doctors execute a gatekeeping function in the Slovenian health system, they are essential to the provision of acute and chronic care, but also for referrals to specialist outpatient services and hospitals, prescriptions and sickness leaves.

Family doctor shortages have resulted in significant problems for population coverage in certain municipalities, including, notably, Ljubljana. In total, an estimated 136 000 people are not currently registered with a family doctor for their common needs.

To address this acute coverage issue, the Ministry of Health has issued decrees in the last six months to increase funding to primary health care and to establish new practices for non-registered individuals. These practices are to be located within the community-oriented primary health care centers (CPHCs). Arrangements include bonuses for family doctors and nurses in family medicine teams who work additional hours in the new practices, providing acute care services and services for chronic care management. Unlike regular primary care services provided at the municipally owned and managed CPHCs that are financed through a mix of capitation and FFS payments by the National Insurance Institute of Slovenia, services provided for non-registered patients are to be paid from the central budget.

These additional practices have already been set up – a total of 64.2 team equivalents are available at 94 offices at CPHC locations – and all those who currently are not and cannot register with a family doctor can apply.

While this is an innovative way to address a pressing issue, it is unknown how this new set-up will support the PHC system sustainably for the future.

Authors

References

- Availability of chosen doctors at the homepage of the Health Insurance Institute of Slovenia, https://zavarovanec.zzzs.si/wps/portal/portali/azos/ioz/ioz_izvajalci

- List of doctors’ offices for persons without a chosen family doctor: https://n1info.si/novice/slovenija/objavljamo-seznam-ambulant-za-paciente-brez-izbranega-zdravnika/

Strengthening primary health care (PHC) has been on the policy agenda in Slovenia for the last decades. In 2016, the process to prepare a PHC strategy was launched. In 2019, the WHO Regional Office for Europe and NIJZ/NIPH conducted an analysis of root causes of challenges in PHC to inform this new strategy. On 26 March 2021, the Ministry of Health (MoH) nominated the Working Group of Primary Health Care Experts, which prepared the document “Entry points for the strategy for the development of primary health care 2022–2031” in dialogue with stakeholders, local representatives, and with professional support from WHO. In autumn 2021, a delegation visited Catalonia to observe their PHC system. The strategy was supported univocally by the Health Council but has not yet been adopted by the National Assembly due to changes of government.

In line with the recent European Strategy for Primary Health Care, the document outlines the following strategic goals:

- Equal access to comprehensive care as close as possible to the population

- Focus on the user and their empowerment

- Comprehensive and integrated treatment

- Quality and safe treatment

- Focus on preventive services

More specifically, it plans changes across several policy areas, including:

Leadership and management

- Outlines establishing an internal structure for PHC with representatives of PHC to strengthen the strategic role of the MoH and a national body for professional support for the development of PHC.

- Plans to define more precisely the roles of other stakeholders for the coordinated development of PHC.

Financing of PHC activities

- Outlines increased public funds for health at the primary level.

- Identifies the introduction of new financing models based on the efficiency and quality of patient treatment for fairer financing of PHC.

- Identifies updating infrastructure and equipment at the primary level.

Provision of human resources and improving working conditions

- Identifies the immediate continuation of existing measures to ensure sufficient personnel resources and appropriate working conditions as a priority.

- To ensure health care access at the primary level for all residents, the strategy identifies (1) updating the network of primary care providers (in the Master Plan of Healthcare Providers) with a needs assessment, (2) introducing rural clinics and (3) improving the care of vulnerable groups through better cooperation between health care providers and local organizations.

- Plans an upgrade of PHC teamwork structures to ensure comprehensive and integrated treatment, including through the expansion of graduate nurse competencies and the establishment of a system of effective cooperation mechanisms between different levels and professional groups.

Digitization and strengthening research to improve quality and safety of care

- Describes the need to further digitalize healthcare through provider and patient e-Health tools like an EHR, tools to support clinical decision-making, and development of data visualizations to support management, quality improvement and governance.

- Outlines the necessity of (1) defining quality indicators for PHC, (2) introducing a system of internal audits and reporting by providers, and (3) establishing a system of monitoring to improving quality and safety at the national level to ensure high-quality and safe medical treatment.

- Prioritizes a user-friendly portal to gather and provide information on the use of health services to empower and involve individuals, including by supporting decision-making when choosing providers.

Certain individual activities are also defined, including the establishment of the tertiary level institute of family medicine.

Authors

References

New pan-European strategy set to transform primary health care across the Region (who.int): https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/13-06-2022-new-pan-european-strategy-set-to-transform-primary-health-care-across-the-region

Albreht T, Polin K, Pribaković Brinovec R, Kuhar M, Poldrugovac M, Ogrin Rehberger P, Prevolnik Rupel V, Vracko P. Slovenia: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 2021; 23(1): pp. i–188.

Integrated, person-centred primary health care produces results: case study from Slovenia. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336184/9789289055284-eng.pdf

Bregant T, Horvat Krstić A, Koprivec J, Ravnikar R, Rotar-Pavlič D, Vračko P. Naj bo primarna raven spet privlačna zdravnikom in dostopna bolnikom. Isis: glasilo Zdravniške zbornice Slovenije. [Tiskana izd.]. Apr. 2022, leto 31, št. 4, str. 21-25, tabele.

Potrjena izhodišča za strategijo razvoja zdravstvene dejavnosti na primarni ravni do leta 2031. Vlada Republike Slovenije. 30 May 2022. https://www.gov.si/novice/2022-05-30-potrjena-izhodisca-za-strategijo-razvoja-zdravstvene-dejavnosti-na-primarni-ravni-do-leta-2031/

In the face of an ageing population and increasing (multiple) chronic diseases, Slovenia has worked to strengthen its management of chronic diseases and noncommunicable disease risk factors. In 2018, Family Medicine Practices were nationally scaled up to improve prevention and care coordination for patients with stable chronic diseases. The practices include a new staffing standard in primary care, particularly in the CPHCs, in the form of an additional 0.5 full-time equivalent of registered nursing support. Patients who visit a practice receive a consultation with a specially trained nurse who assesses their current lifestyle and screens for risk factors and provides regular advice and follow-up.

Due to the shortage of nursing staff across the health system, which was acutely felt during COVID-19, most of the nurses employed in Family Medicine Practices were re-deployed to nursing homes, some hospital departments (if they had previous hospital experience), vaccination points and to perform COVID-19 testing to bolster the frontline response to the virus. This undermined the health system’s key tactic for managing and reducing chronic diseases, weakened primary care’s community-oriented working methods, and, for the nurses, represented a worsening of working conditions as the hours required of them in these seconded posts were much more than in their usual jobs. Previously well-managed preventative programs for chronic care were effectively stopped.

Authors

References

- Emergency instruction of the Ministry of Health to Primary Health Centres from 25 October 2020 – instruction on the possibility of repositioning nurses to other posts within the PHCs and to other providers.

- Order of the MoH on the temporary measures to contain the epidemic of COVID-19 enacted in a legal act adopted on 13 November 2020.

- Order of the MoH on the temporary measures to contain the epidemic of COVID-19 enacted in a legal act adopted on 15 November 2021.

- Explanation on provision of preventative health programs during the times of the epidemic of COVID-19, issued by the MoH on 20 October 2020

4.2.1. Planning and registration of human resources

Health care human resource levels are a matter of frequent discussion and controversy. Issues include past shortages and worker workloads. While the first point reflects planning patterns (or their inadequacy) at the national level in particular, the second is a consequence of organizational aspects of health care. Nevertheless, in general, current policy goals aim to increase the present staffing of health care as there are shortages of physicians, especially in primary care settings, as well as shortages of registered nurses in hospitals and nursing homes.

4.2.2. Trends in the health workforce

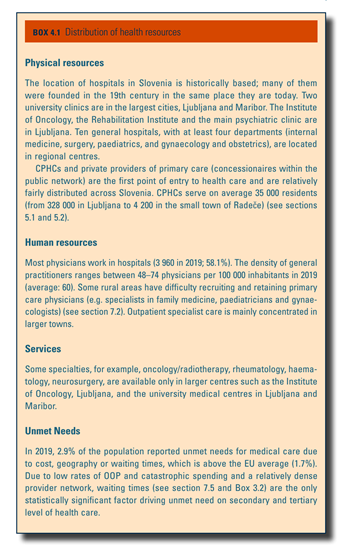

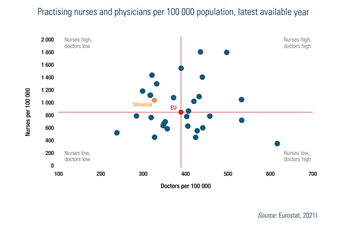

The number of practising physicians in health care has increased by 37% in the last 10 years, from 4979 in 2010 to 6812 in 2019 (NIJZ, 2019). By the end of 2019, 6812 doctors were employed in the health care system, or 326 per 100 000 population. Despite these increases, the ratio of physicians to population remains lower than the EU27 average (389 per 100 000) (Eurostat, 2021l) and most comparator countries (Fig4.2 and Fig4.3). According to national data, in October 2019, there were 134 registered unemployed medical doctors, 86 of them under the age of 29, waiting for their first employment (SURS, 2020a).

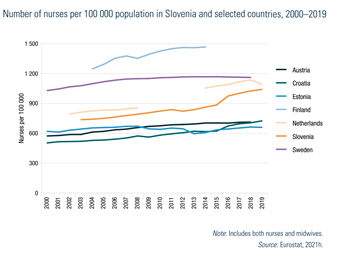

| Fig4.2 | Fig4.3 |

|  |

Personnel shortages, which lead to overburdening of doctors, are most acute in family medicine and paediatrics at the primary level as well as for nursing professionals in hospitals. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted shortages of health professionals, in particular in public health and in primary health care. Two trade unions, the Fides medical union and the Praktikum family doctors’ union, went on strike in 2016, joining secondary level doctors. Consequently, an agreement was reached in 2017 with the MoH to limit the defined patient-to-physician ratio at around 1500 listed patients; when this threshold is reached, physicians are no longer required to admit new patients. This agreement, however, faced interference with implementation (see section 6.1).

Slovenia has a significantly higher number of nursing professionals, at 1041 per 100 000 population in 2019 which is higher than Austria, Croatia and Estonia (Fig4.4). In terms of practising nurses, Slovenia has 1028 nurses per 100 000, which is higher than the EU27 country average (837 per 100 000 population) (Fig4.2). One third of all nurses work in outpatient settings and the numbers are expected to rise further in primary care with the further scaling-up of family medicine model practices, HPCs and MHCs (see section 5.3). Comparatively, the number of nurses working in hospitals is lower than in other more hospital-oriented health systems (NIJZ, 2021a).

Fig4.4

Additionally, the high numbers of nursing professionals are partly misleading because these numbers include both registered nurses (37%; 7996) and vocationally trained nursing technicians (63%; 13 468) (NIJZ, 2020b) (see section 4.2.4).

Because of comparatively low levels of physicians, task shifting to registered nurses was introduced in 2019, especially in primary health care (see section 5.3). Due to lower levels of registered nurses, nursing technicians have assumed responsibilities that are formally competences of registered nurses. As a result, the Nursing Chamber of Slovenia advocates for disaggregating these categories when counting the number of nursing professionals and reversing the ratio of registered nurses to nursing technicians. One suggestion is to downsize the nursing technician population and introduce an additional 3500–4500 registered nurses. Moreover, in 2019, an agreement was reached, enabling nursing technicians to obtain a registered nurse licence after fulfilling certain criteria (see section 4.2.6); around 1500 have thus acquired the status of registered nurses. This reform has since seen challenges to implementation (see section 6.1).

In 2017 and 2018, a project financed by the EU Structural Reform Support Service (SRSS) facilitated the introduction of a geographical planning and forecasting instrument for health professionals, which includes needs and demands by the population, not only the demographic characteristics of the specific health professional populations as had been the practice previously.

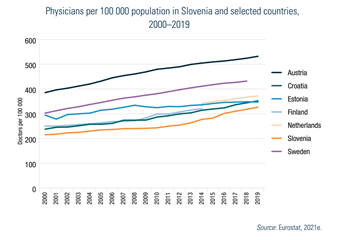

See Box4.1 for more information on the geographical distribution of health workers in Slovenia.

Box4.1

4.2.3. Professional mobility of health workers

Under the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Slovenia was the only republic with a strict numerus clausus system for the health workforce (since 1961). Medical and dental graduates from other Yugoslavian republics helped overcome domestic deficits in provider capacity through internal mobility.

Regulations after 1991, however, halted this type of mobility, but until the financial crisis in 2008/2009, Slovenia remained a destination country for health professionals, mainly medical doctors and dentists, from the area of the former Yugoslavia and the Balkans. After accession to the EU, more mobility was expected from the broader central and eastern European Region, but never materialized (Albreht, 2011). Despite salaries increasing significantly (1996, 2000 and 2008), there are few incentives for cross-border immigration. Available data suggest that to this day most immigrant medical doctors in Slovenia hail from areas of the former Yugoslavia and south-eastern Europe.

Domestic human resource shortages and challenges are increasingly being addressed. By contrast, the freezing of salaries through austerity measures in 2012–2016 has increased the likelihood of emigration of health professionals. Nevertheless, there are no recent published reports on trends in health workforce emigration from Slovenia.

4.2.4. Training of health personnel

Physicians

To work as a physician, basic medical education is available from two medical faculties (Universities of Ljubljana and of Maribor) and lasts six years, after which there is an obligatory six-month internship in emergency medicine. In 2020/2021, there was a numerus clausus of 160 students at Ljubljana and 106 at Maribor. Since 2007, junior physicians enter specialist training directly after their internship through open public tenders twice yearly for specialty training posts, organized by the Medical Chamber. Posts are offered by specialty and by region. Though candidates may apply for different specialties, they can eventually only qualify for one. Depending on the area of specialization, this training can last from four to six years. The number of posts (324 in 2020) is approved by the MoH and presented to the ZZZS.

Since 2009, ZZZS fully finances all medical specialist training in the public system. Competence for preparing and implementing the programme of specializations lies with the Medical Chamber. The Chamber prepares lists of qualified tutors to manage candidates, health care providers and institutions where training can take place. Coordinators for every specialty supervise both the tutors and the registered training institutions. The examination commission at the Medical Chamber conducts the final examination and issues certificates.

Newly qualified medical specialists are committed to the region where they trained, though most doctors stay at the institution in which their careers started.

Nurses

As already described above, there are two overarching types of nursing professionals in Slovenia: nursing technicians and registered nurses. Training of nursing technicians consists of a four-year secondary professional education. Registered nurses go through a three-year post-secondary programme at the first level of the Bologna Process (bachelor degrees) (European Commission, 2016). Community nurses require additional training.

Educational standards are set by universities. The Nursing Chamber authorizes the registration/licensing of nurses and the revalidation of qualifications through continuous professional education (see section 2.8.3). Nursing and midwifery are also two of the regulated professions within the EU.

Eight higher education institutions for health professionals provide university- or college-level training for nurses: University of Ljubljana, University of Maribor, University of Primorska, College of Nursing in Jesenice, College of Nursing in Novo Mesto, College of Nursing in Slovenj Gradec, College of Nursing in Celje and College of Nursing in Murska Sobota. The latter three offer only part-time educational programmes and do not have a concession with the Ministry of Education. As such, they do not receive public funds and instead are funded from private sources, such as admission and teaching fees.

The curriculum for nurses (started in 1993) reflects the principles of primary health care (see section 5.3) and has a strong emphasis on health promotion and prevention. There are several bachelor’s degrees available: general nursing, midwifery, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, sanitary engineering, and orthotics and prosthetics.

4.2.5. Physicians’ career paths

To be able to practise, medical doctors enter a six-month internship in emergency medicine financed by the state budget after graduation. Then, they take the state registration examination, proving their knowledge in emergency medicine. Successful completion of subsequent specialty training (four–six years) results in the doctors’ first licence, which entitles the physician to practise without supervision.

In public institutions, career advances are regulated by the Civil Servants Act (2002, amended in 2008), which allocates to all employed physicians and dentists a position within a number of ranked classes. As part of the Balancing of Public Finance Act (2012), advancement in the career rank classes was frozen, but resumed in 2015.

In primary care, a physician advances from junior specialist to senior specialist, to chief of a service to director. In hospitals, a physician similarly advances from junior to senior specialist. Additionally, he/she may become head of ward, of department or medical director. A supervising superior is responsible for a physician’s evaluation every three years and can propose a regular promotion (one class) or extraordinary promotion (two classes).

4.2.6. Other health workers’ career paths

Nurses

Since 2019, nursing technicians with at least 12 years of experience and who have performed at least 50% of their working time in a particular care area may obtain a special licence as registered nurse in this area, along with corresponding salary increases. This is the result of an agreement between the Nursing Chamber and the MoH, and summarized in Article 38 of the Act Amending the Health Activity Act.

Additionally, there are several second-level Bologna programmes for masters’ degrees in nursing.

Other health care professionals

As with physicians, the basic education for a doctor of dental medicine takes six years, followed by a 12-month internship. Dentists undergo similar procedures as medical doctors to obtain their dental specialty training. Since 2005, there are six specialties: orthodontics, oral surgery, maxillofacial surgery, paediatric and preventive dentistry, periodontology, dental diseases and endodontics.

Basic education for pharmacists lasts 5.5 years. There are two distinct pathways after university graduation: 1) to continue working in health care (community pharmacy, pharmacy attached to a hospital or laboratory); or 2) to opt for a career in industry. There are also several options for postgraduate training.

Physiotherapy basic education is a three-year post-secondary programme at the first level of the Bologna Process, followed by a six-month internship.

Clinical psychology is a specialty available to university graduates in psychology who previously concluded a six-month internship in health care. Specialty training lasts four years.

A four-year public health medical specialty was introduced in 2002, replacing three specialty training programmes (epidemiology, hygiene and social medicine). Within this specialization, there is now a two-semester training course (400 hours) in public health, organized by the Medical Faculty at the University of Ljubljana, which is open to all professional backgrounds and considered the equivalent of a master’s in public health.