-

01 March 2020 | Country Update

Chronic care nurses transferred to other postings in COVID-19 response

7.4. Health care quality

Quality and safety have been identified as fundamental values in the Slovenian health system. Until 2015, health system efforts in quality improvement were explicitly framed in the National Strategy for Health Quality and Safety 2010–2015, published in 2010, but this strategy was neither renewed nor revised. There are several objectives in the area of quality set out in the National Health Care Plan 2016–2025. These include clearly defining the competences and responsibilities of each stakeholder in improving quality and safety, increasing capacity by ensuring human and financial resources, and strengthening training in quality, safety and patient communication. The Plan foresees an update of the set of quality indicators that are currently collected. While this is still to be implemented, some other of its key quality related strategies have been implemented, some described above.

- a project to develop a new adverse event reporting system;

- standardized patient experience measurement in outpatient consultation (Murko et al., 2021) (see also Box5.3); and

Box5.3

- updated survey of patient experiences in acute inpatient care.

Otherwise, reforms in other areas may also influence health care quality. For example, recent changes to primary care service delivery models likely had a significant impact on the quality of primary care provided (Tomšič et al., 2016). In particular, the progressive shift of family medicine practices to Family Medicine Practices (previously called “family medicine model practices”) and the restructuring of HPCs currently under way are changing many aspects of chronic patients’ care (see sections 5.1 and 5.3).

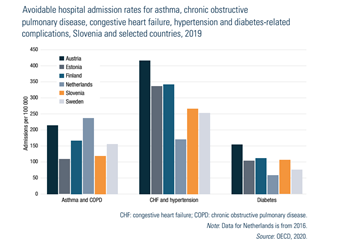

The indicator of avoidable admissions to hospitals is often used to gauge the strength and quality of primary care. Potentially preventable hospitalizations are admissions to a hospital for certain acute illnesses or chronic conditions, such as asthma, COPD, congestive heart failure, hypertension and diabetes, that might not have required hospitalization had these conditions been managed successfully with good outpatient care, especially at the primary level. By this measure, Slovenia fares well compared with other European countries (Fig7.5).

Fig7.5

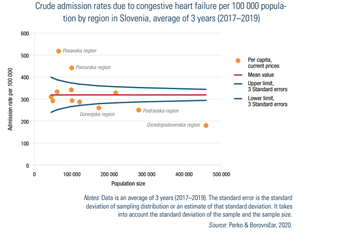

However, the crude admission rates vary significantly by region. The Podravska region is an outlier in terms of admissions due to COPD and asthma, while the Pomurska region is an outlier in admissions due to congestive heart failure (Fig7.6) and hypertension. In all these cases, admission rates are higher than expected, though the Osrednjeslovenska region has a lower than expected rate of admission on three out of the four conditions considered (Perko & Borovničar, 2020). Despite the use of a funnel plot to identify outliers,[10] caution is necessary in the interpretation of these data. First, the data are not adjusted by sex and age, or by the regional prevalence of these conditions. Secondly, different admission rates may be due to different practices in labelling the primary diagnosis in the various hospitals. Thirdly, different admission rates may be due to differences in bed (or staff) availability in regional hospitals.

Fig7.6

The changes of family medicine practices to adhere to model of Family Doctor Practices, completed in 2018, included provisions to establish registries at practice level that would allow monitoring of specific patient groups and to monitor a broad range of indicators. The 2019 report on family medicine practices evaluated performance focusing in particular on identifying people at risk of chronic conditions and monitoring chronic patients by registered nurses (Ministry of Health, 2019). The indicators were mostly process focused, such as measuring HbA1c for patients with diabetes at least once a year. The report found that most practices did not achieve the target values on the indicators considered. There were also considerable differences in the results achieved, pointing to the need to reduce variation in addition to overall performance improvement. These findings must be interpreted in the broader context of a rapidly evolving situation. For example, in 2014 there were 433 family medicine practices operating according to the new model, while in 2018 there were 864 of them. Crude rates indicate that the amount of data available is still increasing (Ministry of Health, 2019), suggesting that adaptations to the new model are still under way in many practices.

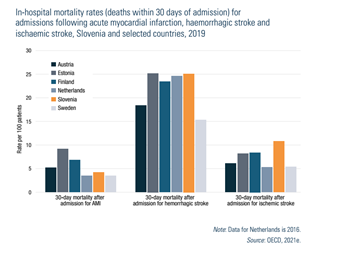

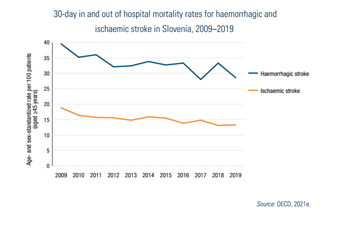

The quality of hospital care in Slovenia is difficult to assess as performance varies, depending on the condition or indicator considered. Compared with other selected countries, the standardized 30-day hospital mortality rate for AMI is low (Fig7.7). Indeed, it is the second lowest in Europe at 4.2 per 100 patients after the Netherlands and Sweden (3.5 per 100 patients each). However, the rate of 30-day mortality following both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke is concerning; Slovenia had some of the highest in-hospital case-fatality rates in Europe in 2009 (OECD, 2012a). Since then, the values have improved for both conditions (Fig7.8). Nonetheless, the country has still above average values, as compared with selected countries and the EU.

| Fig7.7 | Fig7.8 |

|  |

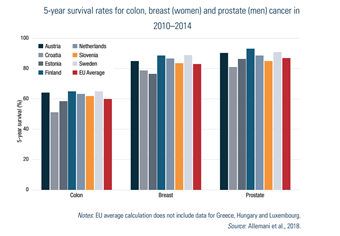

Slovenia’s HSPA report (see section 7.1) considered survival rates for colorectal, breast, lung, prostate, cervical cancer and overall cancer survival rates (Perko et al., 2019; see also Fig7.9). It found most of these indicators were improving. However, the overall survival rate was worse than the EU average. A notable exception was cervical cancer survival, which was stable at a better than EU average rate. The HSPA report included a few other indicators in the quality and safety domain: infant mortality rates, admission-based diabetes-related lower extremity amputations rates, 30-day mortality for AMI and stroke and use of second line antibiotics. The overall assessment of health care quality was good (Perko et al., 2019).

Fig7.9

- 10. The rate of hospital admissions may vary randomly every year. This is why a simple comparison between the admission rates in each region does not necessarily suggest superior performance in one region over another. The random variation is usually considered to be limited to three standard errors above and below the mean value for all hospitals. The standard error changes with the size of the population, giving the characteristic funnel shaped limits. Hospitals outside these limits are considered outliers, having higher or lower than expected rates that require further attention. ↰

In the face of an ageing population and increasing (multiple) chronic diseases, Slovenia has worked to strengthen its management of chronic diseases and noncommunicable disease risk factors. In 2018, Family Medicine Practices were nationally scaled up to improve prevention and care coordination for patients with stable chronic diseases. The practices include a new staffing standard in primary care, particularly in the CPHCs, in the form of an additional 0.5 full-time equivalent of registered nursing support. Patients who visit a practice receive a consultation with a specially trained nurse who assesses their current lifestyle and screens for risk factors and provides regular advice and follow-up.

Due to the shortage of nursing staff across the health system, which was acutely felt during COVID-19, most of the nurses employed in Family Medicine Practices were re-deployed to nursing homes, some hospital departments (if they had previous hospital experience), vaccination points and to perform COVID-19 testing to bolster the frontline response to the virus. This undermined the health system’s key tactic for managing and reducing chronic diseases, weakened primary care’s community-oriented working methods, and, for the nurses, represented a worsening of working conditions as the hours required of them in these seconded posts were much more than in their usual jobs. Previously well-managed preventative programs for chronic care were effectively stopped.

Authors

References

- Emergency instruction of the Ministry of Health to Primary Health Centres from 25 October 2020 – instruction on the possibility of repositioning nurses to other posts within the PHCs and to other providers.

- Order of the MoH on the temporary measures to contain the epidemic of COVID-19 enacted in a legal act adopted on 13 November 2020.

- Order of the MoH on the temporary measures to contain the epidemic of COVID-19 enacted in a legal act adopted on 15 November 2021.

- Explanation on provision of preventative health programs during the times of the epidemic of COVID-19, issued by the MoH on 20 October 2020