-

09 April 2024 | Policy Analysis

Health expenditure in Slovakia set to rise 11.5% in 2024 -

12 December 2023 | Policy Analysis

The health system financing “consolidation package” -

27 July 2023 | Policy Analysis

Amendments to Slovakia’s pharmaceutical reimbursement legislation to combat growing challenges -

30 June 2023 | Policy Analysis

Financial losses at the state-owned insurer (VšZP) and the corresponding recovery plan -

19 September 2019 | Country Update

Fluctuations in revenues by a flexible contribution base for state-insured

3.3. Overview of the statutory financing system

Slovakia’s new government has approved a “consolidation” package of measures (18 in total) to bring down their existing budget deficit. By increasing taxes, fees and other contributions, the new government’s plans are thus far only on the revenue side of public finances and are forecast to bring in an additional EUR 1.96 billion.

Regarding the health system, the major measure included in the new package concerns increasing the employer contribution rate the SHI system by 1 percentage point, from 10% to 11%. The employee contribution remains flat at 4%, while the self-employed contribution rate will also rise, from 14% to 15%. These rate rises will generate an additional EUR 357 million. Before the parliamentary elections in September 2023, all political parties declared interest in raising additional revenues (that is, tax hikes) and increasing the general transfers to the health system from the state budget, while the idea of increasing the contribution rates was not campaigned on. The rising contributions rates for employers and the self-employed has likewise surprised analysts. For example, Dušan Zachar from the Institute for Economic and Social Reforms (INEKO) argued for instead increasing consumption taxes and legalizing co-payments in the health system, while Martin Vlachynský from the Institute of Economic and Social Studies (INESS) pointed out that these rate increases are not linked to quality or quantity metrics.

Additionally, and according to the larger budget proposal, the payment for the so-called “state insured” will reach EUR 2.1 billion next year, which is approximately the same level as in 2023 but a massive increase compared to EUR 1.2 billion in 2022. This high increase was partially driven by the vision to increase the state payment to the level comparable with neighbouring Czechia, among other measures taken in 2023. According to analyst Martin Smatana, in 2022, the Slovak state paid EUR 31 per state-insured person monthly, while in Czechia the payment was EUR 72 per person. This difference decreased in 2023: EUR 60 was spent per capita on the state insured in Slovakia against EUR 78 in Czechia.

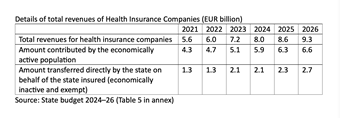

Altogether, the pooling and distribution of revenues to Slovakia’s three health insurance companies will reach roughly EUR 8 billion EUR in 2024, which represents about a 25% jump from 2022 levels (see Table 1). This was confirmed by State Secretary of the Ministry of Health, Michal Štofko, in his interview with the publication Denník N in December 2023. According to State Secretary Štofko, this money should be used to (1) cover the potential debt of state hospitals, (2) increase hospital productivity and (3) provide new resources to introduce a new catalogue of services in outpatient care.

Table 1

Despite this and the other 17 measures in the package, the credit rating agency Fitch downgraded Slovakia’s rating to “A−”. The main reasons for this are

- overall deteriorating public finances,

- wide deficits,

- an uncertain fiscal consolidation trajectory and

- an upward trajectory of debt.

References

https://www.mfsr.sk/files/archiv/66/KONSOLIDACNE-OPATRENIA-2024.pdf [Consolidation package 2024]

https://hsr.rokovania.sk/mf0180772023-41/?csrt=16838386985454613868 [State budget 2024–26]

https://rokovania.gov.sk/RVL/Material/29105/1 [State budget 2024–26]

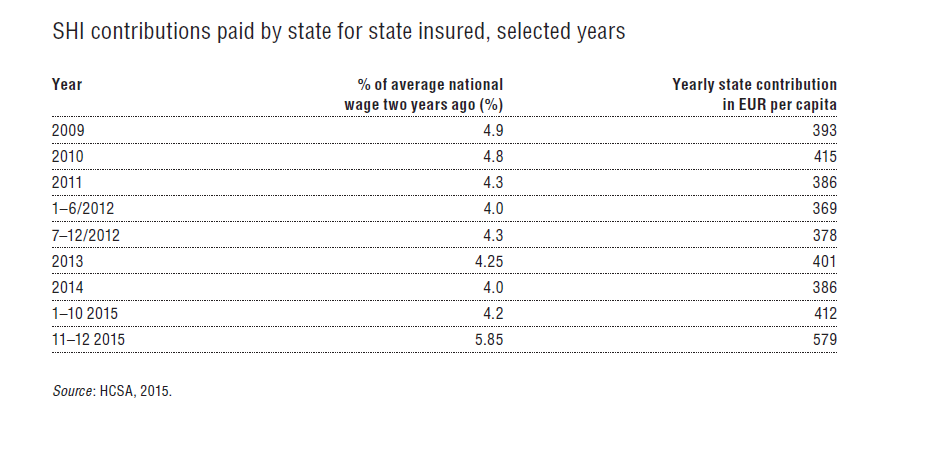

In the last few years, the government has gradually decreased the contribution rate as low as 3.2% at the beginning of 2019. A significantly lower contribution rate for state insured contributes among other factors to financial problems for the GHIC.

Authors

References

Iness (2019) Šachy s poistencami štátu. Available at: https://www.iness.sk/sk/sachy-s-poistencami-statu (accessed 13 August 2019).

https://www.vszp.sk/novinky/vyvoj-hospodarenia-vszp-je-pozitivny-bez-dofinancovania-sektora-neda-udrzat.html

3.3.1. Coverage

Breadth: who is covered?

All residents in Slovakia are entitled to SHI, with the exception of people with a valid health insurance in another country, which may be related to their job, business or long-term residence. People seeking asylum and foreigners who are employed, studying or doing business in Slovakia are also covered by SHI. Those insured are entitled to health care services according to conditions set forth in legislation. Every citizen has an equal right to have their needs met, regardless of their social status or income. The SHI system is universal, based on solidarity, and guarantees free choice of HICs for every insured. Payment of contributions is a condition for receiving health care benefits based on SHI. With the exception of the state insured, whose contributions are paid by the state, all insured are obliged to make monthly advance payments and to settle any outstanding balance on their total SHI contribution annually. If this obligation is violated, the insured are entitled only to emergency care and the health insurance company may require reimbursement of the costs. In practice, around 4% of residents are not covered. This group consists mostly of residents who are officially living and/or working abroad and pay their health insurance in a temporary place of residence.

Despite the strong regulations in the scope of covered services, HICs are eager to attract new insured by offering additional services such as medicine discounts, reimbursing co-payments for some medicines, vitamins or non-health care services; shorter surgery waiting times; broader preventive examinations or a variety of supporting electronical services.

Scope: what is covered?

The Slovak Constitution guarantees every citizen health care under the SHI system according to the conditions laid down by law. The law outlines a list of free preventive care examinations; a list of essential pharmaceuticals without co-payment; a list of diagnoses eligible for free spa treatment; and a list of priority diagnoses (roughly two-thirds of ICD-10 diagnoses). All health procedures provided to treat a priority diagnosis are provided free of charge. Non-priority diseases may be subject to co-payments. However, in practice many non-priority disease treatments are also provided free of charge. Services at a patient’s request, not based on their health needs, or resulting from alcohol or drug abuse are not covered. However, the latter has only sporadically been acted upon.

Every provider is obliged to publish a price list which is visible to visitors and reviewed by a higher territorial unit. This price list must contain prices for nonmedical services and is meant to improve transparency for patients.

Depth: how much of the benefit cost is covered?

Cost-sharing mainly takes place through a system of small user fees for prescriptions and certain health services (e.g. emergency care), as well as co-payments for pharmaceuticals and spa treatments. An act passed in 2006 lowered some of the user fees and in some cases abolished them completely by setting their price to zero. Additionally, recent efforts by the government have aimed to further limit space for doctors to charge for provided services. This effort culminated in April 2014, when a strict policy abolished the practice of HICs reimbursing co-payments for health service. Neither inpatient nor outpatient providers are allowed to demand payments once they have a contract with the patient’s HIC with the exception of some premium services (e.g. an option to choose a surgeon in a hospital, etc.). See section 3.4.2 for more information).

In recent years, the Slovak health system has faced several problems with regard to pharmaceuticals, creating a growing list of challenges for policymakers. For example. Slovakia has a high overall consumption level of medicines in comparison to other OECD countries, but research shows low levels of generic and biosimilar medicine usage [1].

There is also a general lack of availability of innovative medicines, and managed entry agreements (MEAs) for new medicines on the Slovak market saw only seven new contracts between 2018 and 2021. In the field of oncology, only 20% of indications with confirmed effectiveness out of 135 were reimbursed in 2021 and only one oncology innovative medicine was categorized (that is, was put on positive medicine lists) that same year [2]. As such, expenditure for the reimbursement of medicines through the exception regime (including orphan drugs and those such as Cisplatina and Dakarbazín that left the market, in addition to innovative medicines that are mainly for oncology patients) is now worth over EUR 50 million annually, as many critical medicines were not categorized, with prescribing physicians resorting to sending reimbursement requests directly to the health insurance companies (HICs) [3]. Overall, these problems have contributed to a lack of transparency and predictability of the environment [3] as well as the decreasing bargaining power of the state, and there has been a gradual departure of multinational companies from the Slovak market [2].

In an effort to address these issues, a new amendment to Act No. 363/2011 Coll. on the scope and conditions of payments for medicines, medical devices, and dietetic foods from public health insurance and on amendments to certain acts was approved in June 2022 [4]. The key changes include the following:

- Changes in the categorization process, including the introduction of consultations before proceeding and simplified MEAs, which alone brought 57 new medicines (69 new indications) onto the market in 2022; the Ministry of Health is now responsible for closing MEAs, which previously was done by the HICs and involved negotiations with all three.

- Transparent rules for decision making under the exception regime and upper limit on the volume of funds (3.9% of the allocated funds for HICs – postponed via legislation to 2024 after HICs nearly hit this upper limit (roughly EUR 60 million) in the first few months of 2023 alone).

- Adjustments to the QALY threshold that is now based on GDP per capita from two years prior. For regular medicines, 3 times GDP per capita (for 0.33–1 QALY gained) or 2 times GDP per capita (for 0–0.33 QALY gained) is applied; medicines for a rare disease or an innovative treatment have higher thresholds of up to 10x GDP per capita.

- Requiring the three HICs to make the list of approved medicines through the exception regime available online.

- New procedures for determining, changing and cancelling reimbursement groups, as well as changes in the revision of reimbursements, referencing or entry of generic and biologically similar drugs.

Authors

References

[1] Tesar T., Golias P, Masarykova L., Kawalec P., Inotai A. (2023) The Impact of Reimbursement Practices on the Pharmaceutical Market for Off-Patent Medicines in Slovakia, In Front Pharmacol. 2021 Dec 13;12:795002. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.795002. PMID: 34966285; PMCID: PMC8710743 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8710743

[2] Babeľa Róbert (2023) Novela zákona 363/2011: kde sme a kam kráčame? Presentation for CEEHPN. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/63c7dbc6ff4f92106ce2bd6d/t/647f01f44a096110aea9e9d2/1686045191518/6_presentation_oncology_Babela.pdf

[3] Löffler Ľubica, Pažitný Peter, Kandilaki Daniela (2022) Lieková politika v širších rozpočtových súvislostiach. Available from: https://healthcareconsulting.sk/sites/default/files/liekova_politika_v_sirsich_rozpoctovych_suvislostiach.pdf

[4] Ministry of Health (2022) Parlament schválil prelomovú liekovú reformu. Available from: https://www.health.gov.sk/Clanok?parlament-zakon-lieky-prelomova-reforma

3.3.2. Collection

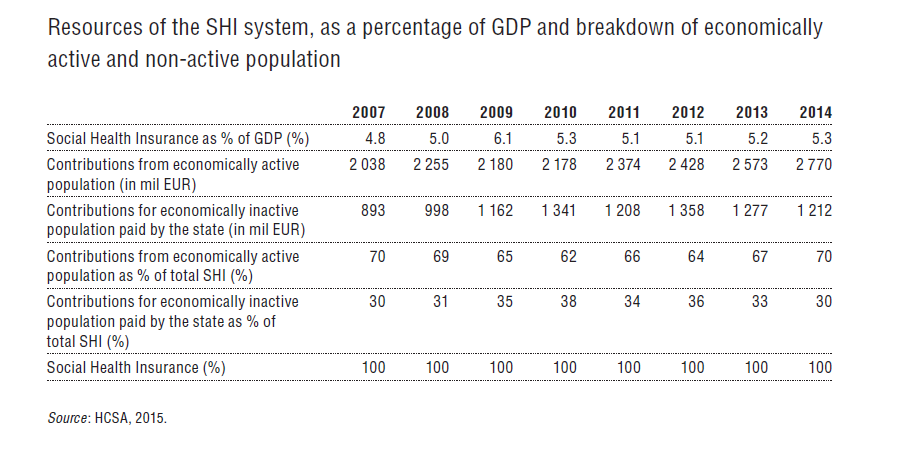

The SHI system is financed through a combination of contributions from the economically active population and state contributions on behalf of the state insured. SHI resources include (1) contributions from employees and employers; (2) contributions from self-employed persons; (3) contributions from voluntarily unemployed; (4) contributions by the state for the state insured; and (5) contributions from dividends. Contributions are collected and administered by HICs.

Employees pay 14% of their gross monthly income as a mandatory insurance contribution. Out of this percentage, employees pay 4% and employers 10%.

Self-employed people use 14% of the assessment base for income tax divided by a predefined coefficient. Self-employed people and employees with more serious permanent disabilities are entitled to discounts up to 50% on contributions, as are their employers.

The maximum assessment basis for employed and self-employed is dependent on the average wage in the national economy, multiplied by five. The minimum assessment base is determined only for the self-employed and equals half of the national average wage two years before. For 2016 this corresponds with a minimum monthly contribution of €60.6 and a maximum contribution of €600.6. Contributions are paid directly to HICs, and in the case of multiple jobs there is an annual accounting for those insured. Disabled employees pay half the SHI contribution rate.

The introduction of the lower assessment base policy for low-income workers in January 2015 reduced the SHI contributions of approximately 600 000 workers, increasing in turn both their net income and labour costs. The policy enabled employees who earn below €570 per month to have their assessment base for SHI reduced. Depending on the monthly income of employees, the maximum reduction of the assessment base can amount to €380 per month. The expected loss of SHI revenue due to this policy is €180 million for 2015. This amount should be fully compensated via higher contributions by the state for state insured.

Voluntarily unemployed are obliged to pay the same contribution as employed individuals. However, voluntarily unemployed pay the whole 14% themselves.

The contribution for state insured is paid on behalf of economically inactive individuals, i.e. predominantly children, students up to the age of 26, unemployed, pensioners, persons taking care of children aged up to 3 years, and disabled persons.[4] These groups make up some 3 million residents in Slovakia. Contributions for the state insured, which are paid from general taxation by the Ministry of Health, were set by law at 4.2% (based on the average wage two years before) for 2015 and are estimated to average 4.3% in 2016. The 4.2% rate was in effect during January–October 2015, while in November and December there was an increased rate of 5.8% to cover extraordinary expenses due to the introduction of a lower assessment base for low-income workers and higher physician salaries. Indeed, to minimize the volatility of finances, state contribution rates have frequently been used to offset predicted losses in contributions of the economically active population (see Table3.4 and Table3.5).

| Table 3.4 | Table 3.5 |

|  |

Dividend contributions from domestic or foreign activities are burdened with 14% SHI contributions, with the maximal assessment base set at 60x the average industry income from two years before, i.e. €41 480 for 2016.

- 4. Disability is assessed in process in competences of Ministry of Social Affairs. ↰

3.3.3. Pooling of funds

Health insurance contributions are collected directly by HICs from employers, self-employed, voluntarily unemployed and the state on behalf of economically inactive persons. In order to compensate HICs for more expensive patients (i.e. higher risk portfolio), 95% of SHI contributions are redistributed among HICs using a risk-adjusted scheme.

The risk-adjustment scheme has been reformed many times and since 2004 has been administrated by the HSCA (see Table3.6). Details of the redistribution procedure are regulated by the Ministry of Health on an annual basis. The HSCA is also in charge of supervising the redistribution process. The HCSA is also responsible for administering the central register of insured. Risk-adjustment is performed on a monthly basis and is accounted annually.

Table3.6

Until July 2012 the redistribution scheme between health insurance funds used the risk-adjusters’ age, gender and economic activity of insured individuals categories. Predictive ability of this model was approximately 3% and hence “penalized” HICs that had chronic and expensive patients in their portfolios (HPI, 2014b). This was particularly true for the GHIC, which was the only insurer in 1994 and still covers a relatively large group of elderly and more complex insured (often state insured).

In order to improve the fairness of the redistribution, a new redistribution mechanism was implemented in July 2012. It added to the risk-adjustment system 24 PCGs, which are based on the consumption of certain amounts of daily defined doses of drugs within the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical group classification over a 12-month period. Taking into consideration that approximately 30% of HICs’ expenditure has been on pharmaceuticals, this model significantly improved the predictability and fairness of the redistribution scheme. As a result, the GHIC recorded a 7% increase in revenue in the first year of the new mechanism at the expense of the privately owned Union and Dôvera.

As of 2015, the risk-adjustment scheme in Slovakia has an estimated predictive ability (R2) of 19.6% (HPI, 2014b). The risk-adjustment formula and indexes of PCGs is updated on a yearly basis. Given the change of redistribution after introducing PCGs and consequently the pattern of allocations among HICs, several adjustments have been made (see Fig3.7) that are often the subject of debate among HICs and the Ministry of Health.

Fig 3.7

Regulation of HICs’ profits

Since 2004 all three HICs competing on the health insurance market in Slovakia are joint-stock companies. Across the three competitors, there has been a broad variation in profit and ability to pay dividends to shareholders. During 2009–2013 the proportion of dividends paid to shareholders of all HICs out of SHI contributions was roughly 3%, i.e. €377 million. However, the majority of dividends are paid out by Dôvera, since the GHIC and Union have very low profits (see Fig3.8). Dôvera is owned by a private equity company that directly benefits from these dividends. It obtained the necessary cash flow to pay the dividends via long-term loans, while Union lowered its capital to create an accounting profit.

Fig 3.8

On 20 March 2024, the Ministry of Health published Decree No. 55/2024, which defines the amounts of expenditure for each type of health care in the budget for each of the three health insurance companies (HICs) for 2024 (the so-called Programme Decree).

Health insurance expenditures are expected to be 11.5% higher than in 2023, amounting to EUR 7.68 billion in 2024. The primary drivers of the increase in expenditures are hospitals (19.3% annual increase), medical devices (18.5%) and outpatient specialized services (11.4%), as captured in Table 1.

Table 1

The budget, despite the fact that there is a fixed payment for the state’s policyholders from 2024 onwards, is calculated as in previous years, that is, the sum of expenditure for existing policies, for policy changes and subtracting the planned austerity measures, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Impact of existing policy measures’ growth on 2024 expenditure

Without taking any new measures, the expenditure on health services will grow by roughly EUR 521 million. The largest increase is due to wage growth in the sector, followed by medicines and medical devices, inflation and ageing.

Each year, the budget assumes that health workers’ wages will grow at the same rate as the average wage in the economy. The total of these automatic wage increases for all hospital and ambulance staff is set at EUR 253 million for 2024, representing a 7.7% annual increase in the basic component of the wage and the components linked to it.

Due to the categorization of new medicines and medical devices that already took place in 2023, a natural increase is also budgeted for this item, with an expected increase on medicines and medical devices by a total of EUR 124 million.

The budget also covers the natural increase due to inflation and ageing. Expected CPI inflation, which was forecast by the Finance Ministry when the budget was drawn up, is projected at 4.9% for 2024. The natural growth in health care output, and hence in ageing expenditure, is budgeted at EUR 43 million.

Impact of policy changes on 2024 expenditure

EUR 283 million is earmarked in the decree for measures and priorities of the ministry that go beyond natural growth, as explained in the previous section. The largest policy change is the additional financing of institutional health facilities to the amount of EUR 261 million above the growth in personnel costs and inflation, prioritized for the following purposes:

the top-up funding of hospitals under the competence of the Ministry of Health for an amount of EUR 191 million, and

to cover the increase in production due to the reduction of waiting times, the introduction of DRGs and the implementation of the optimization of the hospital network, with a budget of EUR 70 million.

The top-up is aimed at activities that are not sufficiently taken into account and covered under today’s payment mechanism. Without the increase, further indebtedness of hospitals would be imminent for 2024. Slovakia is already facing a lawsuit from the European Commission before the European Court of Justice for late payments by state hospitals. The Commission is calling on Slovakia to address the problem systemically and this increase should be a basic and first of many initiatives to improve financial state of state-owned hospitals.

Depending on the success of the implementation of the austerity measures (see below), additional resources may also be brought into outpatient healthcare. The full savings potential amounts to EUR 100 million; the realized savings will be redirected to the outpatient sector, the final amount of which may be lower and will depend on the success of the implementation of the measures

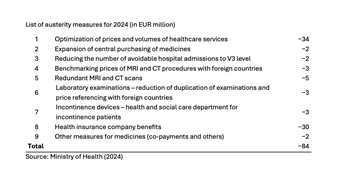

Austerity measures planned for 2024

The potential for austerity measures (stemming from the 2022 spending review) is estimated at EUR 84 million. Successful implementation of austerity measures is a prerequisite for the implementation of the new catalogue of procedures in the outpatient sector. A list of these measures is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Authors

References

All three of Slovakia’s health insurers reported first-quarter losses in 2023, according to the Health Care Surveillance Authority (HCSA, 2023). The problem is expected to worsen, with a cumulative loss of approximately EUR 300 million expected for 2023, representing approximately 4% of the health insurers’ total revenues.

The biggest losses and most problems are faced by the state-owned VšZP, with annual losses estimated to be around EUR 240 million and its equity, that is, the value of its assets, falling into negative values by the end of the year. This would result in its liquidation as an insurance company.

Therefore, VšZP’s Supervisory Board, upon request from the Ministry of Health (MoH), prepared an analysis of the reasons for the losses along with a proposal for recovery measures at the end of May 2023. The Supervisory Board approved the proposal, and the MoH directed VšZP to implement 13 of the measures in June; the Supervisory Board is responsible for the supervision of their implementation.

Approximately 40% of VšZP’s losses (and similarly of other insurance companies) stem from errors on the budgeting side. When the MoH switched to programme-based expenditure budgeting in 2022/2023, it began dictating minimum spending amounts to all insurers by care group. However, the MoH does not budget revenues in this detailed way. As a result, VšZP’s revenues have been underestimated by approximately EUR 93.5 million when compared to the way in which the minimum expenditure was set by Decree 100/2023 in March 2023.

Another approximately 40% is accounting shifts. The programme budget is made so that on a cash basis, the revenues and expenditures are balances. However, insurance companies are public limited companies with double-entry accounting and naturally there is a shift between the cash and accounting view. This became significant in 2023, as several amendments to the law shifted the timing of payments for some items that were not covered by revenue in the budget. On the accounting side, though, these are ledgered as a cost. For VšZP, this represents approximately EUR 90 million of the expected loss.

The remainder (roughly 20% of expected losses), is health care expenditures, which are higher than the MoH budgeted for in Programme Decree No. 100/2023. The primary driver of the increase is pharmaceuticals, whose growth is approximately four times the budgeted plan. This is due to the amendment to the Medicines Act in June 2022 (see related Policy Analysis on pharmaceutical reimbursement legislation and reforming categorization processes). Many more medicines are coming onto the market and entering the categorisation process than in previous years, that is, being added to the positive lists of reimbursed medicines, and the impact of this is approximately EUR 50–60 million higher than budgeted for VšZP. Thus, while medicines were expected to grow by around 2% in 2023, the increase is currently estimated at 8% or more. In addition to medicines, spending on laboratory diagnostics or inpatient care is growing faster, which is, for example, due to the opening of two new hospitals in Slovakia (Bory Hospital and Cardiocentrum Šaca in Košice).

As the Ministry of Finance does not have sufficient resources to cover VšZP’s losses in full and savings have to be found on the VšZP side, the recovery plan for VšZP introduced in June 2023 and its 13 measures aim to save approximately EUR 52 million by the end of the year.

The measures are divided into two parts – administrative savings (EUR 11 million) on operations and savings to eliminate above-standard increases on care (EUR 41 million). The latter is primarily aimed at reducing expenditure on laboratory diagnostics and boosting allocative efficiency of company resources. As a part of the effort of the MoH to realise these savings, the CEO of VšZP, R. Strapko was dismissed and interim management is currently in charge (TASR, 2023).

Even if savings are achieved, VšZP will need a top-up of EUR 165 million (that is, 3.8% of the VšZP’s annual revenue) to avoid receivership status next year and additional liquidity problems as early as December 2023.

The Ministry of Finance has not yet promised whether it will proceed with the refinancing, as they are waiting to see if VšZP can enact savings measures this year before guaranteeing additional funding. In May, VšZP already experienced cash problems in paying its liabilities, which is why the MoH proceeded to advance payments. Thus, cash is not currently an issue for the payment of invoices, but only until December 2023, when this payment will be cleared. The MoH therefore has until the end of the year to resolve the situation, but with national elections on 30 September 2023, there is no guarantee that any top-up funding will be able to materialise in time to prevent VšZP’s dire liquidity issues.

References

HCSA (2023). Straty zdravotných poisťovní nemajú rovnakú príčinu (Health insurers’ losses do not have the same cause). Úrad pre dohlad nad zdravotnou starostlivosťou (Healthcare surveillance authority). Available from: https://www.udzs-sk.sk/blog/2023/05/09/straty-zdravotnych-poistovni-nemaju-rovnaku-pricinu

TASR (2023) Minister Palkovič odvolal z funkcie šéfa Všeobecnej zdravotnej poisťovne (Minister Palkovič dismissed the head of the General Health Insurance Company). SME. Available from: https://domov.sme.sk/c/23192316/strapko-vseobecna-zdravotna-poistovna-vszp-odvolanie.html

3.3.4. Purchasing and purchaserprovider relations

Purchaserprovider relations are based on selective contracting under regulation of the Ministry of Health to ensure accessibility and quality of services. The Ministry of Health defines a minimum of clinical FTEs in ambulatory care and a minimum number of beds per specialty in acute care that a HIC has to cover in each of the SGRs. Furthermore, to ensure availability of health care for everyone, the Ministry of Health reintroduced in 2012 a list of selected state providers (i.e. a compulsory network) that has to be contracted by all HICs, irrespective of their quality and effectiveness. This minimum coverage requirement also applies to emergency services, GPs and pharmacies. The HCSA is responsible for monitoring purchasing of health care services.

Apart from these requirements, HICs are free to contract with other providers. Therefore, HICs may have different contracts with different providers and negotiate quality, price and volumes individually. A list of contracting criteria, which includes technical and personnel requirements, quality indicators, accessibility and other factors, is published every nine months by the HICs (see Table3.7).

Table3.7

Having met criteria set by a HIC, the contractual parties can settle on conditions, including the scope and price of health services. The minimum duration of a contract is one year, but in practice, contracts are negotiated on a regular basis even several times per year. HICs are required to publish rankings of providers, as well as a list of contracted entities as of 1 January every year.

In practice, tariffs and volume of contracted services are not constrained by the aforementioned criteria. It is open to individual negotiations, which has resulted in providers having different contracts with different HICs. In fact, according to the HCSA, differences in contracted prices of HICs between the same groups of inpatient specialties reached up to 180% (HCSA, 2015).

The freedom of HICs to set tariffs and prices and their oligopolistic market power has stimulated health professionals to group into networks to strengthen their negotiation position vis-à-vis HICs. Examples include the Zdravita association of outpatient physicians, which negotiates on behalf of approximately 2000 members or the Slovak Medical Chamber, which negotiates on behalf of some of its 18 000 members. In 2015 the Slovak Medical Chamber also founded the Union of Outpatient Providers to negotiate the contracts with HICs.