-

19 June 2025 | Policy Analysis

Major amendments to public health insurance and ehealth legislation -

07 January 2025 | Country Update

ePrescription helps patients avoid excessive pharmaceutical co-payments -

09 November 2024 | Policy Analysis

Advancements in healthcare digitalization -

06 September 2024 | Country Update

Definition of Telemedicine in Czech legislation -

04 April 2024 | Country Update

New functions of eHealth application

4.1. Physical resources

4.1.1. Infrastructure, capital stock and investments

Infrastructure

Of the 194 hospitals in Czechia in 2019, 154 were acute care hospitals (with 57 422 beds) and 40 were LTC hospitals (3078 beds). From the 1990s through 2013, Czechia set about decreasing acute care hospital beds and increasing LTC beds, though this trend slowed between 2014 and 2019. Czechia recorded an acute bed density of four beds per 1000 population in 2019, which was lower than neighbouring countries but similar to the EU average (see Fig4.1). Additionally, 119 specialized therapeutic institutes had a total of 16 937 beds in 2019. Specialized therapeutic institutes do not have the legal status of hospitals; they provide specialized follow-up care, especially for long-term or chronically ill patients. These include beds for psychiatric care (8610 for adults and another 210 for children in 2019), hospices (491 beds) and rehabilitation care (2407 beds) (ÚZIS, 2020a).

Fig4.1

The average length of stay in acute care hospitals stood at 5.7 days in 2019 (down from 6 days in 2013), the lowest among neighbouring countries. The occupancy rate of acute care hospital beds, at 68.6% in 2019, is the lowest recorded value since 1975 and lower than in Germany (79.1% in 2018) and Austria (72.9%), but higher than in Slovakia (65.9%), and is a result of a lack of nurses in acute care hospitals (Eurostat, 2022). Nurses often leave this area of care as it is very exhausting. As a result, not only does the occupancy rate decrease, but wards are often either partially or fully closed (MZČR, 2020a).

In principle, regulation of hospitals occurs through HIFs’ registration and contractual processes (Health Service Act, 2011). Quality and safety requirements must be fulfilled, too, though the number of beds in hospitals is not explicitly regulated. Providers reduce or expand their capacities according to agreements with those HIFs with whom they have contracts, and these agreements are guided by anticipated patient demand. In anticipation of lower demand or insufficient personnel, excessive beds mean higher operational costs, and as such are reduced.

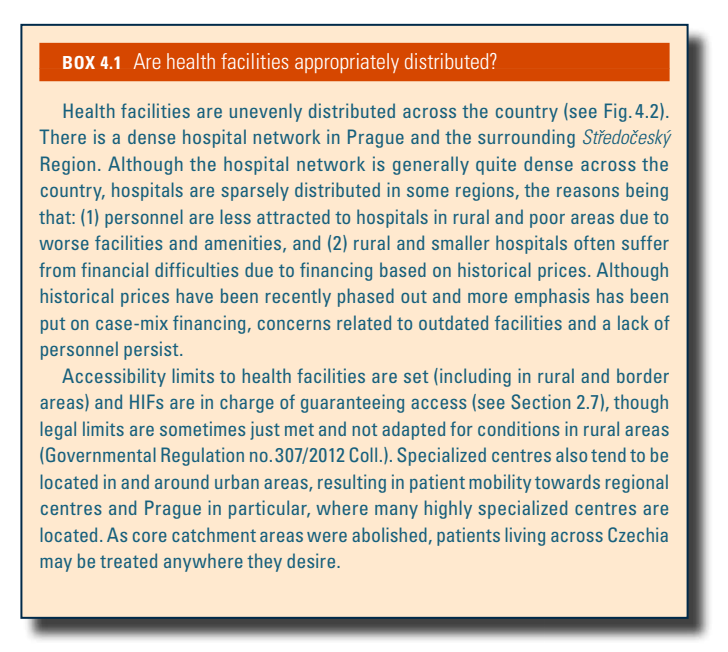

Similar to other countries, specialized centres are concentrated in urban areas, while nursing care is rather prevalent in rural areas, though not missing in big cities (see Box4.1). Note that bigger acute care hospitals also include LTC wards. Fig4.2 shows the distribution of hospitals in Czechia in 2019.

| Box4.1 | Fig4.2 |

|  |

Current capital stock

Included in Czechia’s 154 acute care hospitals in 2019 are:

- 24 hospitals run by MZČR and other state bodies (ministries), including 10 university and military hospitals (36.0% of total bed capacity);

- 69 regional and district hospitals run by regional governments, including both budgetary and corporatized hospitals (38.2%);

- 27 municipal hospitals, including both budgetary and corporatized hospitals (7.6%); and

- a few single-specialty hospitals, such as maternity care hospitals (18.2%) (ÚZIS, 2020a).

In contrast to most inpatient facilities, almost all outpatient providers are privately run (mainly run by self-employed individual physicians).

With no comprehensive surveys of property conditions, it is difficult to objectively assess the state of physical resources, though anecdotal evidence and substantial investments from EU structural funds suggest that there have been some improvements in recent years. The state of physical resources in smaller hospitals is thought to be generally worse, as investments were predominantly allocated to larger facilities. Some form of ad hoc appraisal of conditions is usually used when planning future investments, though there are no formalized procedures that would facilitate formal assessments.

Regulation of capital investment

Renovations of hospital infrastructure are, in theory, financed by HIFs through their reimbursements for services. On the provider side, however, reimbursement revenues are usually insufficient for capital investments. In state-owned hospitals, investments are often supplemented by transfers from state or regional budgets. Decisions on using revenues and transfers for capital investments lie with individual hospital management teams, though they must enable hospitals to at least fulfil the minimal technical requirements set by an amendment to the Health Service Act (2011). As upkeep has long been underfinanced and facilities need repairs, university and state-owned hospitals have recently begun to receive state subsidies for improvements. Recent programmes through the European Regional Development Fund have also targeted smaller regional hospitals to improve care quality in these facilities. New national investment plans include seven major strategic investments to selected teaching and state-owned hospitals to improve infrastructure and maintain the current scope and quality of care, while also creating modern and pleasant environments for patients; these investments amount to CZK 12 billion (information provided by MZČR on 29 March 2022). Capital investments in the private sector are not regulated if financed from private resources.

Investment funding

In 2019, MZČR expenditure on capital investments, that is, transferred funds on top of HIF reimbursements, amounted to nearly CZK 2 billion, decreasing 15% from 2018 (CZK 2.4 billion) and 37% from 2015 (CZK 3.2 billion). These largely cover the purchase of equipment and renovations for state-owned hospitals, including for acute care, LTC and palliative care, both for children and adults (MFČR, 2016, 2019b, 2020a).

Other hospitals may apply for EU funds, which MZČR then allocates; EU funding contributes substantially to capital investments, has supported the creation and modernization of psychiatric wards within hospitals and is expected to reach CZK 50 billion over the next five years. Investment priorities, set by MZČR, are aligned with Health 2030 to include modernizing emergency wards and support for nursing care, public health and eHealth initiatives (MZČR, 2020a).

Hospitals may also apply for REACT-EU funds, which was in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These funds (CZK 22 billion) will go towards improving the health system through the Integrated Regional Operational Programme. Hospitals may further apply for subsidies from the Operational Programme Environment, the National Recovery Plan (Národní plán obnovy) and the Modernization Fund.

Other investments include European Economic Area and Norway Grants, which have financed over 140 health-related projects amounting to CZK 1.2 billion since 2004. These have recently gone towards strengthening patients’ roles within the Czech health system, child mental health and disease prevention.

There is no reliable information available on investments in private facilities, especially for outpatient care. Public–private partnerships are not common in the Czech health system.

4.1.2. Medical equipment

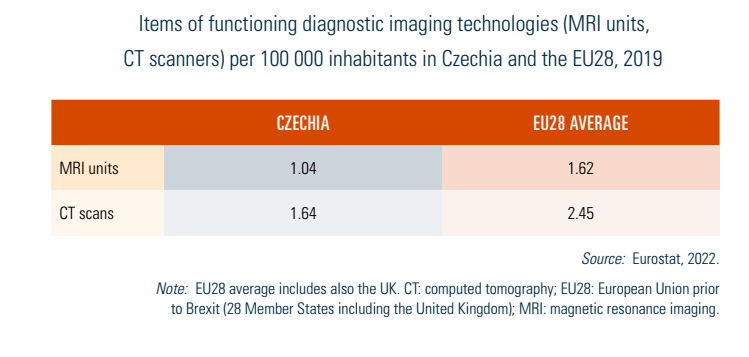

Proposals to purchase equipment for facilities are submitted to the Equipment Committee at MZČR, which considers the equipment’s need based on existing infrastructure. All equipment purchased using state or SHI funds above CZK 5 million is subject to committee approval. Czechia had 1.64 computed tomography (CT) scanners per 100 000 inhabitants in 2019, with an overwhelming majority in inpatient facilities (1.48); though increasing by nearly 70% between 2000 and 2019, this remains under the EU average (2.45). A similar trend exists for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units, which increased from 0.17 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2000 to 1.04 in 2019, also lower than the EU average (see Table4.1).

Table4.1

Although a lack of devices is not a problem, devices ageing is. There are also large differences between Prague and rest of the country, though medical facilities in Prague also serve inhabitants of other regions (see Box4.1). Czechia is also incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics into the health system. As of 2022, 12 da Vinci and 2 Cyberknife systems were in use in Czechia, among other AI products (icobrain, Brainomix), and Czech scientists have recently developed and applied AI to detect chronic diseases. The use of AI for health in Czechia is expected to accelerate when ethical and liability issues are fully resolved.

Box4.1

4.1.3. Information technology and eHealth

The share of Czech households connected to the Internet increased from 67% in 2013 to 81.7% in 2019 and Internet use is comparable to neighbouring countries (ČSÚ, 2021c; Eurostat, 2022). The share of Czechs accessing the Internet for health purposes stood at 52% for men and 72% for women in 2019, exceeding the EU averages (49% for men and 60% for woman) (ČSÚ, 2021c). NZIP websites in particular have useful health information (see section 2.8).

All HIFs have websites for communicating with their members; and members can view their record of administered and reimbursed care electronically (for example, mojeVZP and e-komunikace). Moreover, HIFs (minus VZP) have a common site (https://szpcr.cz/) for communicating with contracted providers, reducing the administrative burden for all parties. Some form of sharing records has existed at the regional level for about five years, particularly between emergency services and hospitals.

After being long fragmented into individual HIF initiatives, the first plan for nationwide data collection was unveiled in 2011, though implementation was paused because of a lack of funding. Nevertheless, MZČR adopted a national strategy for health system digitalization in 2016 for 2016–2020, which set the foundations, including electronic prescriptions and digital sick notes.

After a voluntary pilot period, electronic prescriptions were fully launched in 2018, requiring providers to issue them. This enabled patients to request prescriptions via phone or email without a physical visit, something greatly used throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Phone consultations have also become more widespread and accepted. Digital sick notes were fully launched in January 2020, whereby providers electronically notify the social security system about a sick worker. Sick workers must still notify employers, but can now provide employers with an electronic copy. Other excusal notes (such as caring for a sick household member) still require the submission of physical documentation.

Nearly all health facilities in Czechia employ IT for reimbursement and accounting, and most large facilities have websites to provide patients with an overview of their services; 18.5% of facilities allow patients to book appointments online in Czechia, while 16.2% offer online consultations and a further 32.5% allow patients to request prescriptions online without needing to speak to a physician (ČSÚ, 2021c). Some private providers have built virtual clinics (see Table2.2).

Table2.2

Both the COVID-19 pandemic and the Act on eHealth (2021) have significantly accelerated digital health priorities in Czechia. The Act on eHealth (2021) introduced a basic legislative framework, defined obligations and standardized rules for communication, information sharing and data protection. It did not introduce electronic health records, though did introduce conditions for the safe sharing of documents among providers or between providers and HIFs. Patients have the right to receive transcripts of information shared about them at public administration contact points, although not all providers participate yet.

Amendments to two laws – on public health insurance and electronic healthcare – passed the Czech Senate in June 2025. Both amendments now await the President’s signature and are expected to come into effect in January 2026.

Act on Public Health Insurance

According to the Minister of Health, the amendment aims to enhance the efficiency of healthcare financing, strengthen the role of health insurance funds and promote preventive care, with the overall goal of improving access to healthcare.

A key change is the restructuring of mandatory accounts within health insurance funds. The amendment abolishes reserve accounts and introduces a new account for public benefit activities (Fond obecně prospěšných činností), which will support initiatives aimed at improving healthcare quality. This includes partial financing of physicians’ specialty training, DRG activities conducted by the Institute of Health Information and Statistics (ÚZIS), and selected activities of patient organizations. Notably, health insurance funds will now be able to support residency training positions in specific regions or specialties, a role previously limited to the Ministry of Health, which is required to offer equal conditions nationwide.

The amendment also increases the permissible allocation for health promotion programmes from 0.5% to up to 3% of collected premiums. It intends to expand the possibilities of health insurance funds to offer benefits to insured individuals who take good care of their health. However, insurance funds may only access the increased budget if their financial situation is balanced.

Further changes include the possibility of receiving covered health services abroad up to the amount of local reimbursement if these services are unavailable in Czechia or if it is more efficient for the health insurance fund. This concerns both long-term and repeated use of care. Health insurance funds will be allowed to contract directly with foreign providers for such care.

Reimbursement for medical devices will now fall under a separate Act on the Categorization of Medical Devices, aimed at ensuring more flexible and timely responses to technological advances and evolving patient needs.

The amendment also aims to increase the accessibility of dental care. It responds to the ban on the use of amalgam dental fillings. Insurance funds will therefore reimburse their adult insured persons for the cheapest available white filling, or partially reimburse a higher-quality alternative.

Other passed changes include a report on the network of contractual providers of outpatient care in the fields or services specified in the governmental regulation on the local and temporal accessibility of health services (with the exception of pharmacies) and home care. This report will be published annually, by the end of November, by each health insurance fund. Furthermore, the health insurance funds will have the opportunity of centralized procurement for supplies of “centre” medicinal products for highly specialized providers. Also, the selection procedures at the regional offices before concluding a contract with the insurance fund will be eliminated. Decisions to contract a new provider will rest solely with the insurance funds.

Health insurance funds criticized the abolishing of the reserve account and the obligation to finance the management of the DRG system. The Ministry of Health countered by saying that the reserve accounts were not used in the past, even when the specific situations which the reserve accounts were established for occurred.

Furthermore, following substantial criticism, a proposed clause that would have allowed health insurance funds to seek (partial) reimbursement for care provided to individuals injured while committing illegal activities was removed from the final version.

Act on Electronic Healthcare

This amendment seeks to improve communication across the healthcare system and promote safer, higher-quality service delivery through digital tools.

The instruments introduced include:

- Electronic vaccination card

- e-Referrals

- Central register of preventive examinations

- Electronic vouchers for medical supplies (for example, crutches, bandages)

The “core” register is expected to be expanded to include, for example, data on medical fitness to drive motor vehicles, possession of weapons or ammunition permits. The shared health record will be divided into two parts – an emergency record with key data (for example, blood type, allergies) and a record of the results of preventive and screening examinations.

Medical check-up requirements for older drivers will also change. Instead of beginning at age 65, mandatory check-ups will now start at age 70. Drivers will no longer need to carry physical proof of these check-ups; police will verify them via digital records.

References

https://www.senat.cz/xqw/xervlet/pssenat/historie?cid=pssenat_historie.pHistorieTisku.list&forEach.action=detail&forEach.value=s5450 (Senate Press No. 103)

Starting from January 2025, patients only pay deductible co-payments for partially reimbursed medicines at the pharmacy up to the protective limit relevant to them. Prior to this, people also encountered co-payments exceeding this limit and were quarterly refunded by their health insurance fund (HIF).

This change was possible due to improvements in the monitoring of protective limits for deductible co-payments. Deductible co-payments are now registered online in the ePrescription system, and so pharmacists know when dispensing whether patients have reached their set limit based on their age. From 2025, the ePrescription system will also contain information on recipients of invalidity pensions. From 2026, it will contain information on the degree of invalidity as well.

Patients will continue to pay the non-reimbursable part of the co-payment, as well as the price of medicines that are not covered by statutory health insurance, as they do today.

In October 2024, the government approved an amendment to the Act on eHealth (passed in 2021), to fundamentally modernize healthcare and make access to health information more efficient. The amendment includes important digitisation projects that will enable easier management of health data for citizens and medical personnel and will contribute to improving the functioning of the entire system. This motion now has to pass through the Chamber of Deputies and Senate (in both, the government coalition currently holds the majority) and be signed by the president to be effective.

The amendment will bring a whole range of new tools, including eŽádanka (eReferral), further development of the EZKarta application (see below), as well as the addition of data in the patient registers, such as information on the ability to drive motor vehicles or hold a firearms license (linked through the departments of the interior and transport). All of this will follow on from the already approved and currently tested functions of electronic healthcare.

New functions of the eHealth application

The electronic health application EZKarta newly includes vaccinations administered between 2010 and 2022 and reimbursed from statutory health insurance. This is an addition to records that have already been displayed in the application: all vaccinations since 2023 (both reimbursed and not reimbursed from statutory health insurance) and all COVID-19 vaccinations. Vaccinations paid out-of-pocket between 2010 and 2022 are not displayed.

Authors

References

The Ministry of Health has launched the new electronic health application “EZKarta”. It builds on a previous application (Tečka), which was created and widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic for digital vaccination and test certificates. In March 2024, the EZKarta (originally Tečka) gained a new function. It now contains information on a user’s full vaccination history since January 2023, including COVID-19 vaccinations. It is also possible for parents/guardians to access the information on their child's vaccination history and/or other persons who grant permission to sharing. Users will also be able to share this data with their GP.

The EZKarta is a gateway to new electronic healthcare services in Czechia. In 2024, the application is expected to bring additional functionalities such as a map of healthcare providers and extracts of information from the National Health Information System. In the future, users should have their medical documentation available directly in the application, such as discharge reports and laboratory results, if the given provider makes them available.