-

28 March 2025 | Country Update

A new regulation defines eligible funding projects for transformation fund in the hospital sector -

28 March 2025 | Policy Analysis

New act reforms GP remuneration and expands access to primary care in Germany -

31 January 2025 | Policy Analysis

The Hospital Care Improvement Act came into force on 1 January 2025 -

30 October 2024 | Country Update

Reform on hospital remuneration and planning -

04 August 2023 | Country Update

Federal and state governments agree on key points for hospital remuneration reform -

07 February 2023 | Policy Analysis

The reform of hospital remuneration and planning has started – first draft law expected in summer 2023 -

27 January 2023 | Country Update

De-budgeting: new plans for pediatricians to be exempt from volume ceilings in ambulatory care -

12 December 2022 | Policy Analysis

Proposal for fundamental reform of hospital remuneration -

22 July 2022 | Country Update

Short-term reform of inpatient remuneration for pediatrics, pediatric surgery, and obstetrics

3.7. Payment mechanisms

With the Hospital Care Improvement Act (Krankenhausversorgungsverbesserungsgesetz, see policy analysis “The Hospital Care Improvement Act came into force on 1 January 2025” from 31 January 2025), a so-called transformation fund with €50 billion for hospitals has been introduced. Between 2026 and 2035, hospitals can apply for investment funding to support structural reforms and adapt to the changes initiated by the Hospital Care Improvement Act.

On 21 March 2025, the Federal Assembly of Germany’s 16 federal states adopted the Regulation on the Administration of the Transformation Fund in the Hospital Sector (Krankenhaustransformationsfonds-Verordnung). The regulation defines which types of projects are eligible for funding, including [1, 2]:

- Concentration of acute inpatient care capacities

- Restructuring of an existing hospital site into an intersectoral care facility (a hospital combining basic inpatient care, short-term nursing care, and outpatient physician care)

- Development of telemedical networks

- Establishment of centres for the treatment of rare, complex, or serious diseases

- Formation of regional hospital networks

- Creation of integrated emergency centres (combining inpatient emergency rooms and outpatient emergency practices; see country update “Establishment of Integrated Emergency Centres as part of an emergency care reform” from 30 October 2024)

- Closure of hospitals or departments

- Expansion of additional training capacities for health professionals

Authors

On 1 March 2025, the Act to Strengthen Health Care (Gesundheitsversorgungsstärkungsgesetz) came into force, including important changes to the remuneration of general practitioners (GPs).

In the German Social Health Insurance system, the remuneration of ambulatory care physicians is subject to regional budgets that limit the number of services a physician can bill per yearly quarter. In addition to restricting service provision, the system has also meant that patients with ongoing treatment needs, such as those with chronic conditions, must visit their physician each quarter in order for the physician to be able to bill the related services.

With the new act, the Ministry of Health aims to expand primary care services by abandoning the volume ceilings for GPs and improving efficiency.

The act introduces the following changes [1]:

- All services provided by GPs will now be fully reimbursed without volume caps. A similar de-budgeting policy was already implemented for paediatricians in April 2023 (see country update “De-budgeting: new plans for pediatricians to be exempt from volume ceilings in ambulatory care” from 27 January 2023).

- GPs can now bill flat rates for patients with chronic conditions for up to four quarters at once, covering services for the respective disease.

- Flat-rate payments for basic services will be introduced, depending on factors such as practice opening hours and whether they offer home visits or care in nursing homes.

The political opposition and physician associations have mostly welcomed the law. However, the health insurance funds have voiced concerns about the projected additional costs, estimated at €400–€500 million per year and criticized the law for lacking incentives to expand the availability of services in areas with low physician density [2, 3].

The next step will involve negotiations among the self-governing associations to agree on how to implement the new regulations.

In addition to changing the GP reimbursement, the act also includes further measures [1]:

- Access to medical aids will be simplified for people with severe diseases or disabilities. A recommendation from a physician will now be sufficient for patients receiving treatment in specialized centres.

- The age limit of under 22 years for accessing emergency contraceptives will be lifted for victims of sexual abuse or rape.

Authors

References

Context

Germany’s health system is characterized by strong sector boundaries between inpatient care (hospitals) and outpatient care (mainly office-based physicians). Hospitals are primarily paid through case payments (diagnosis-related groups, DRGs). The DRG system and general budget constraints have put hospitals under increasing financial pressure, evoking societal and media debates about access to and quality of hospital care. Additionally, the quality of inpatient care differs widely between hospitals. So far, hospital planning, a task of the 16 federal states, does not systematically include quality criteria.

Impetus for the reform

In 2022, the Government Commission for Modern and Needs-based Hospital Care proposed a comprehensive hospital reform, including

- a partial substitution of the DRG-based hospital payment system with flat fees,

- linking hospital planning and remuneration to the existence of certain hospital structures and processes with so-called service groups, and

- categorizing hospitals into different levels of care based on which service groups they can offer (see the policy analysis “Proposal for fundamental reform of hospital remuneration” from 12 December 2022).

In 2023, the legislative process started with the Hospital Care Improvement Act (Krankenhausversorgungsverbesserungsgesetz).

Main purpose of the reform

According to the Ministry of Health, the reform intends to

- improve treatment quality in hospitals,

- secure access to care, especially in rural areas,

- foster integrated, cross-sector healthcare, and

- relieve hospitals of bureaucracy and economic pressure.

Content

With the reform, the main content includes the introduction of the following policies:

- 65 service groups: Hospitals must meet certain requirements for staffing, equipment, and departments to apply for a service group (for example, general internal medicine, stroke unit). The respective federal state assigns these groups, which determine reimbursement.

- A new reimbursement model: The DRG-based hospital payment system has been partly replaced with flat fees. Reimbursement for inpatient operating costs will ultimately include three components: nursing staff, flat fees, and residual DRGs, derived for every service group based on average costs. The share of the flat fees depends on nursing costs and variable material costs.

- Intersectoral care facilities: A new hospital form, intersectoral care facilities, will be able to provide outpatient physician care, outpatient and short-term inpatient care for older people, outpatient hospital services (for example, day surgery), and some inpatient treatments (at least covering geriatrics and general internal medicine). The aims are to secure access to basic services, especially in rural areas, and to lower sector boundaries.

- A so-called transformation fund: Between 2026 and 2035, hospitals can apply for investments from a transformation fund with €50 billion to meet the requirements to apply for one or more service groups, mergers and closures of hospitals, or conversions into intersectoral care facilities.

- Staffing levels: For physicians (as in place for nurses) and assessing the need for staffing levels for other professional groups like midwives or physiotherapists.

- Measures to lessen bureaucracy: For example, regarding accounting procedures.

Implementation

The act passed parliament in October 2024, got approved by the federal states in November, and entered into force on 1 January 2025. Federal states will assign service groups to their hospitals in 2025 and 2026. The conversion of the remuneration system will take place between 2027 and 2029.

Authors

A new Hospital Care Improvement Act (Krankenhausversorgungsverbesserungsgesetz), passed by the Bundestag on 17 October 2024, will partially replace the current DRG-based remuneration system with flat fees and introduce newly defined service groups (for example, basic internal medicine and stroke units) as remuneration criteria. The reform is set to take effect on 1 January 2025.

The Act is based on proposals from the Government Commission for a Modern and Needs-based Hospital Sector, which presented a comprehensive hospital system reform in December 2022 (see Policy Analyses from 12 December 2022 and 7 February 2023). On this basis, the Federal Ministry of Health, government factions and the state health ministries developed and agreed on key reform points in July 2023 (see Country Update from 4 August 2023).

Authors

After months of discussion, the federal and state governments agreed on key points for hospital remuneration reform (See Policy Analyses of 12 December 2022 and 7 February 2023). Not all recommendations proposed by the Government Commission were accepted. As recommended, the current remuneration with DRGs will largely be replaced by flat rates for services provided. In addition, newly defined service groups will be a remuneration criterion. However, it was not possible to reach an agreement on the introduction of the proposed “three levels of hospital care”. Based on these key points, an initial draft law should be available by the end of summer 2023, and the changes should come into force in January 2024.

Authors

Based on the third statement and proposals from the

Government Commission for a Modern and Need-Based Hospital Sector [1],

the Federal Minister of Health and the Ministers of Health in the 16

Federal States started discussions on a fundamental reform of hospital

remuneration in January 2023.

In its coalition agreement from

2021, the Federal Government agreed on reforms in the hospital sector,

especially to expand the Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG)-based

remuneration through the introduction of flat fees and to develop a new

instrument for hospital planning based on defined service groups and

hospital levels. For this, the Federal Minister of Health appointed an

independent Government Commission to develop recommendations. The

Commission published its proposal in December 2022, which combines the

remuneration via flat fees with the new instruments of defined service

groups and hospital levels (see Policy Analysis from December 2022).

Since

2004, hospital remuneration in Germany has been – apart from capital

costs – based entirely on caseloads via DRGs. The Government Commission

argues in its report that the current system leads to an increase in

inpatient cases. Further, an international comparison shows that

inpatient numbers are generally higher in Germany, especially for

planned procedures like hip and knee replacements and avoidable hospital

admissions like asthma or congestive heart failure [1]. A large number

of hospitals, including many small ones without basic emergency

facilities like stroke units, further characterize Germany’s health

system.

Hospital remuneration is subject to federal law, but

the states are in charge of hospital planning. Therefore, the Federal

Minister of Health needs a common ground with colleagues from the states

to realize the main aspects of the planned reform. So far, many

stakeholders in politics and the health sector have shown agreement with

the principle recommendations [2–5]. One potential challenge will be to

define homogeneous service groups and hospital levels between the

states.

Authors

References

[2] https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=140625&s=krankenhausreform

[3] https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=140576&s=krankenhausreform

[4] https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=140472&s=krankenhausreform

[5] https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=140321&s=krankenhausreform

[6] https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=16&aid=229491&s=krankenhausreform

The Federal Minister of Health announced on 26 January 2022

that a process of de-budgeting for pediatricians is underway. Therefore,

pediatricians in ambulatory care will be prospectively exempt from

Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) volume ceilings [1, 2].

The

remuneration of ambulatory care physicians in SHI is based on a

practice-based volume of standard services calculated for each physician

and yearly quarter. The volume of standard services limits the overall

amount that a physician can bill per quarter, and services beyond the

volume limits are reimbursed with a lower amount.

Authors

On 6 December 2022, the Government Commission for a Modern and Needs-Based Hospital Sector submitted its proposals for a reform of the hospital remuneration system. According to the Minister of Health, the current remuneration system based on caseloads incentivizes hospitals to treat as many cases as possible at the lowest possible cost [1]. The commission proposes that the treatment of patients in hospitals should be based more on medical and less on economic criteria. Therefore, the Commission proposes a remuneration system depending on three new criteria: provision of services, levels of care, and service groups [2]:

1) Compensation for upfront services

2) Definition of hospital care in three levels

Hospitals are to be classified into three care levels and funded accordingly:

- Primary care – basic: medical and nursing care, such as basic surgeries and emergencies.

- Regular and specialized care: hospitals that offer additional services compared to basic care.

- Maximum care: for example, university hospitals.

The first-level hospitals are further divided into two groups: 1) hospitals that ensure emergency care (Level 1n) and 2) those that offer integrated outpatient/inpatient care (Level 1i).

3) Introduction of defined service groups

Hospitals are currently treating certain cases all too often without the appropriate personnel and technical equipment, such as heart attacks without a left heart catheter, strokes without a stroke unit, or oncological diseases without a certified cancer centre. Therefore, departments are to be assigned to more precisely defined service groups.

The Commission recommended a gradual implementation of the regulations over a transitional period of five years [1].

On 11 July 2022, the Government Commission for a Modern and

Needs-Based Hospital Sector released its first recommendation on

pediatric and obstetric care. Within the last 20 years, the number of

pediatric wards and hospital beds has declined, while the number of

inpatient cases has increased. The Commission argues that this

development is presumably, among other things, due to economic pressure

on hospitals, creating an incentive to increase the number of cases

despite a reduction in the number of hospital beds [1]. Accordingly, the

Commission proposed a reform of inpatient remuneration for pediatrics

and obstetrics, including additional, non-performance-based funding as a

first step [1].

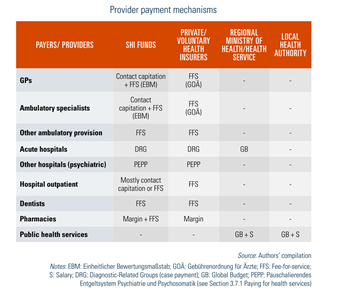

3.7.1. Paying for health services

Table3.4 outlines the various provider payment mechanisms employed within the health system. The rest of this section provides more detail of the payment methods and processes in various subsectors.

Table3.4

Public health services

Public health services mainly take place in a community setting. The multitude of tasks are performed by separate departments in approximately 375 state agencies, as public health services are a state responsibility and state laws regulate details of provision and scope. The majority of public health services are provided at the municipal level (see section 5.1 Public health). State agencies responsible for public health services receive the vast majority of available funding via fixed budgets from the states, and employees are salaried. On a smaller scale, fee-for-services is partly also relevant for e.g. issuing professional opinions and registering health professionals.

Primary care and specialized ambulatory care

Services in ambulatory SHI care provided by office-based physicians (GPs and specialists), dentists, pharmacists, midwives and many other allied health professionals are subject to predetermined price schemes. The most strictly regulated and sophisticated reimbursement catalogues have been developed for physicians and dentists. There are two fee schedules per profession, one for SHI services and one for private treatments. Other price schemes, such as those of the statutory accident funds, are based in large part on these two fee schedules. The following subsections provide details for physicians (in primary and specialized care, including psychotherapists) but these are quite similar for dentists.

Payment of physicians in statutory health insurance settings

The payment of physicians by SHI is not straightforward but is subject to a process involving two major steps. First, the sickness funds make total payments to the regional physicians’ associations for the remuneration of all SHI-affiliated doctors, in lieu of paying the doctors directly. The only exception is the possibility to conclude selective contracts in the context of integrated care (see sections 3.3.4 Purchasing and purchaser–provider relations and 5.4.3 Inpatient care). Second, the regional physicians’ associations distribute these total payments among SHI-accredited physicians according to a “Uniform Value Scale” (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab – EBM).

Overall remuneration

The overall remuneration has three components. The first core component is a morbidity-based overall remuneration, which arises from the treatment requirements of the patients, a regional orientation value and the number of insured people per sickness fund. Since 2009 the amount of overall remuneration of care provided by SHI-affiliated physicians has been negotiated on an annual basis between the Regional Associations of SHI Physicians and the regional associations of the sickness funds. SHI physicians’ remuneration remains subject to a ceiling, even though allocation to the individual funds is on the basis of the treatment needs of their members in comparison with the amount in the preceding period. The second component is the sickness funds’ ability to increase payments to overall remuneration if an unforeseeable need for provision of treatment arises (e.g. an epidemic). The third component is remuneration of individual services that the sickness funds are required to pay at fixed prices over and above the morbidity-based overall remuneration. These eligible services, such as immunizations, screening tests or ambulatory surgery, are not subject to volume ceilings.

Payment of fees

In a second step, the Regional Associations of SHI Physicians share the overall remuneration among their members in accordance with the national Uniform Value Scale and the “fee allocation scales” agreed at regional level with the sickness funds in the individual “fee allocation contracts”. All services that can be provided by physicians for SHI remuneration are listed in the Uniform Value Scale. While the coverage decision is made by the Subcommittee on Method Evaluation of the Federal Joint Committee (see section 2.7.3 Regulation of services and goods), a separate joint committee at the federal level, the Valuation Committee, is responsible for the Uniform Value Scale. The Uniform Value Scale describes the various services that can be charged by SHI physicians (§87 SGB V) and therefore performs the function of a benefit catalogue and is binding for all practising physicians and for the ambulatory care of all those insured through the SHI system.

Services are expressed not in monetary form but as points in the Uniform Value Scale. SHI physicians report their total number of points for services provided to their regional association at the end of each quarter. Since January 2009 a practice-based volume of standard services has been calculated for each SHI physician and quarter. The volumes of standard services set the volume of services that a physician can bill in a defined period and that are payable at a pre-agreed fixed monetary value per point (Euro Fee Code) (§87 SGB V). The physician is notified of the prospective volume of standard services at the beginning of each quarter. The volumes of standard services differ from the expenditure ceilings that previously applied in that the care requirements of the insured are taken into consideration with regard not only to the specific group of physicians but also to the individual practice. A volume of standard services is calculated by multiplying the case rate specific to the physicians’ group by the number of cases of the physician and the morbidity-based weighting factor. The number of cases that a physician can cover is subject to a quantity limit in advance. Cases that are above 50% of the specialist group average are only included in the calculation of the volume of standard services in a graduated form. If a physician exceeds the volume of standard services, this has a regressive effect on the amount that he or she receives for the service in question.

Since 2010 the extension of specialist physician services has not been at the expense of family physicians and vice versa. Nearly all services paid for out of limited morbidity-based overall remuneration are subject to a volume ceiling. Qualification-based additional volumes steer the volume of what are known as “discretionary services”, such as acupuncture and urgent house calls, for nearly all groups of physicians. Distribution volumes specific to groups of physicians for volumes of standard services and qualification-based additional volumes aim to allocate fees as equitably as possible. The Regional Association of SHI Physicians and Sickness Funds have leeway at the regional level to decide the services for which they will form qualification-based additional volumes and how they calculate payment of these services.

Each SHI physician is allotted a volume per quarter that consists of the volume of standard services allocated to the medical practice and any qualification-based additional volume allocated. It is based on the volume of services of the practice in the same quarter of the preceding year. The volume is a quantity limit up to which a practice receives payment for its services at the prices of the Uniform Value Scale. Volumes of standard services or qualification-based additional volume services are remunerated at a graduated price. The amount of the graduated price depends upon how many standard services and qualification-based additional volume services all specialist physicians and family physicians have billed beyond these limits: 2% of the volume allocable to specialists and family physicians is set aside for payment of these services. There are flexible offsetting possibilities between the volume of standard services and the qualification-based additional volume. If a practice does not exhaust its volume of standard services, correspondingly more qualification-based additional volume services can be billed at the prices set out in the Euro Fee Code, and vice versa.

Size of fees

The income of SHI-affiliated physicians is comparatively high, partly as they have further sources of income in addition to that from SHI, in particular income from treating privately insured patients and direct patient payments. According to the Federal Association of SHI Physicians, physicians achieved an average practice turnover per practice owner of €325 450 in 2017, with an average annual surplus of €168 770 per practice owner. The average practice turnover per GP was €339 164 in 2017. The highest turnover is received by internists and radiologists, while the turnover of psychotherapists is comparatively low (Zentralinstitut für die kassenärztliche Versorgung in Deutschland (ZI), 2019). Regarding revenues, it should be remembered that they do not reflect the net earnings of a medical practice. To see these, labour costs, expenditure on materials and outside laboratory work as well as expenditure on rent/leasing and other expenses have to be deducted. According to OECD data, the annual income of a self-employed GP in Germany was the equivalent of US$ 153 786 in 2015, while that of a self-employed specialist physician was US$ 187 858 on average (OECD, 2020d). Therefore, the income of physicians in independent practice was between three and four times greater than the national average annual income of US$ 48 035 in 2015 or US$ 49 813 in 2018 (OECD, 2020a).

Payment in private delivery settings

For privately paying patients, payment of health professionals is organized differently. For physicians and dentists, the catalogues for private tariffs are valid in ambulatory as well as inpatient care, and for patients paying out of pocket as well as those using PHI. They are based on fee-for-service and are determined by the Federal Ministry of Health, which is advised by the professional bodies concerned. In the Catalogue of Tariffs for Physicians, each procedure is given a tariff number and a certain number of points, which – multiplied with a point value of €0.058 287 3 – is the single charge rate. In addition, the maximum charge rate is indicated, which is 3.5-fold higher than the single rate, but for most services physicians charge a 2.3-fold rate and for certain services they may charge only a 1.7-fold rate.

Furthermore, the Catalogue lists the requirements for reimbursement, such as the duration, performance, documentation or limits concerning the combination of several tariff numbers. However, the Catalogue does not reflect daily practice very well. Many services are subsumed under more general items, such as counselling on preventive self-medication and lifestyle (No. 34; single charge rate: €17.49 and 2.3-fold rate: €40.23 in the Catalogue of Tariffs for Physicians). The list of “individual health services” presents a selection of “services deliverable on demand for patients” from the Catalogue of Tariffs for Physicians. Services presented there may be (proactively) offered to patients paying out of pocket in addition to the comprehensive range of SHI benefits. However, the services may only be provided as a supplement to the SHI catalogue of benefits. The list of individual health services contains e.g. services that make sense medically in individual cases but do not number among the responsibilities of SHI (e.g. special immunizations for vacation travel).

The prices for the provision of services in private settings are not set uniformly in most of the other health service professions. However, the associations representing the individual health service professions, for example physiotherapists or nonmedical practitioners, make recommendations on fees that patients and individual service providers can use as a reference and that can serve as a basis if different provisions are not contained in the treatment contract.

Remuneration for ambulatory physician care is usually higher for PHI patients (under GOÄ) than for SHI patients (under EBM). This leads to inequalities in the form of the physicians’ preferred treatment of PHI patients (see section 7.2 Accessibility). In 2018 the Scientific Commission for a modern remuneration system (Wissenschaftliche Kommission für ein modernes Vergütungssystem – KOMV) was founded with the aim of proposing reform plans for the remuneration system in ambulatory care. Recommendations were presented in January 2020, such as the “partial harmonization”. This includes the uniform definition of medical services and their relative cost assessment. However, prices should be negotiated separately for SHI and PHI further on (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG), 2020h; Wissenschaftliche Kommission für ein modernes Vergütungssystem (KOMV), 2019).

Inpatient care

Since the Hospital Financing Act of 1972, hospitals have been financed through two different sources: “dual financing” means that investments are financed through the states, while operating costs are financed through the sickness funds, private health insurers and self-pay patients via remunerations for hospital services (for more details on hospital investment see section 4.1.1 Infrastructure, capital stock and investments). Sickness funds (and others) finance most operating costs, including all costs for medical goods and personnel costs. They also finance the replacement of assets with an average economic life of up to three years, or maintenance and repair costs. Financing of operating costs is the subject of the negotiations between the individual hospitals and the sickness funds.

The German hospital sector has undergone substantial changes since 1993, particularly through the introduction of budgets and prospective payment mechanisms, and the possibility of making a profit or a loss (abolition of the (prime) cost-covering principle), as well as extended opportunities to provide ambulatory treatment. The introduction of a payment system based on DRGs was the most important reform in the acute care hospital sector since the introduction of dual hospital financing in 1972. The SHI Reform Act (2000) obliged the self-governing bodies (the German Hospital Federation and the associations of the statutory sickness funds and private health insurers) to select a universal, performance-related prospective case fee payment system that takes into account clinical severity (case-mix) based on DRGs. DRGs are meant to cover all operating costs for personnel and treatment, as well as board and accommodation. Reimbursement via DRGs is applied for all inpatient services (except psychiatry) in acute care hospitals and covers all patients and all payers.

The staged introduction represented an innovative approach to policy implementation, which has been characterized as a “learning spiral”, outlining long-term roles, objectives and timeframes but allowing governmental actors and corporatist organizations within the self-governance of SHI to issue and refine regulations and to further develop the German diagnosis-related groups (G-DRG) system on a continuous basis. To a hitherto unseen degree, the Federal Ministry of Health was given – and initially indeed carried out – authority to decide on required tasks if self-governing corporatist bodies did not fulfil the tasks delegated to them by law within the defined time schedule.

The self-governing bodies opted for the Australian Refined DRG system 4.1 in June 2000, but could not come to a consensus on the basic characteristics for the future DRG system, which were subsequently defined by the Federal Ministry of Health through the Case Fees Ordinance (based on the Case Fees Act). The Case Fees Act (2002) and the 1st Case Fees Amendment Act (2003) determined the steps required for the gradual introduction of the DRG-based payment system and a phased withdrawal of the mixed payment system (convergence phase). Thereby, hospitals were given the opportunity to adjust to the transition from individual budgets based on historical expenditure to a uniform price system at the state level. The full implementation of the DRG-only price system was planned for 2007 but was postponed to 2009 by the 2nd Case Fees Amendment Act.

In 2010 the uniform price system at the state level became effective. Annual hospital budgets are negotiated between individual hospitals and sickness funds, and deviations from the agreed budget are partially compensated. If the actual hospital revenue in one year exceeds the agreed hospital revenue budget, the hospital has to pay back 65% of the additional revenue (while in the opposite case, i.e. if actual revenue is less than agreed, it will receive 20% of the shortfall).

The G-DRG system represents a patient classification system. The system unambiguously assigns treatment cases to clinically defined groups (i.e. DRGs) that are distinguished by comparable treatment costs. In the G-DRG system, assignment of treatment cases to a DRG is based on a grouping algorithm using the hospital discharge dataset as a basis for a variety of criteria: principal diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, medical procedures, patient characteristics (gender, age, weight of newborn children), mode of admission, discharge disposition (e.g. death) and length of stay. Due to ongoing diversification, the number of DRGs increased over the Australian version to 824 in 2004 and to 1292 in 2020. Costs for certain cost-intensive services or expensive drugs are additionally reimbursed via supplementary fees. The precise definition of the individual DRGs is set out in the most current version of the DRG-definition handbook. Reimbursements for costs that are not covered by DRGs (e.g. new diagnostic or therapeutic measures) can be negotiated between hospitals and sickness funds.

The cost weights for use in the G-DRG system are calculated based on hospital data. The German National Institute for the Reimbursement of Hospitals (InEK), which is funded by the self-governing bodies, provides the organizational structure to maintain and further develop the G-DRG reimbursement system and is responsible for calculating cost weights. To derive DRG classifications and cost weights, InEK relies on case-based cost data, which are collected by a sample of German hospitals. Besides that, each German hospital is required to provide InEK with hospital-related structural data (e.g. the hospital’s ownership, number of beds, number of nursing personnel and costs for nursing education) and case-related claims data annually.

Recently, a fundamental alteration to the G-DRG system was introduced. Because of nursing staff reductions in hospitals, which were observed during the years after the introduction of the G-DRG system, the Nursing Staff Empowerment Act (2019) instructed the self-governing bodies to exclude the costs for nursing personnel from the DRG case fee remuneration. Starting in 2020, individual costs of nursing staff in acute care hospitals are fully covered by the sickness funds, while all other operating cost are covered by DRGs.

During the implementation of the G-DRG system for acute care hospital services, the remuneration for psychiatric and psychosomatic services based on standard per diem charges remained unchanged. In 2009 the Hospital Financing Reform Act instructed the self-governing bodies to develop a new remuneration system for psychiatric and psychosomatic hospital treatments. The legislative framework for the new system is regulated by the Psychiatry Remuneration Act, which came into force in 2013.

As the self-governing bodies could not come to a consensus on the basic characteristics for the psychiatric and psychosomatic reimbursement system, the Federal Ministry of Health initially set a framework for the so-called PEPP system (Pauschalierendes Entgeltsystem Psychiatrie und Psychosomatik – PEPP), which is now being refined by the self-governing bodies. The PEPP system represents a patient classification system for day-based payments and covers inpatient as well as outpatient hospital services. Treatment cases are assigned to clinically defined groups with comparable costs (i.e. PEPPs) based on diagnoses and procedures. The PEPP system in 2020 comprises 84 PEPP groups. Costs for certain special services or expensive drugs are additionally reimbursed via supplementary fees. As for the DRG system, InEK is in charge of calculating PEPP cost weights based on hospital data.

Until 2017 hospitals could implement reimbursement via PEPPs voluntarily. Since 2018 the application of the PEPP system has been mandatory for all hospitals providing psychiatric and psychosomatic services. The transition from individual budgets based on historical expenditure to a uniform price system at the state level is planned to be completed in 2024.

Pharmaceutical care

The financing of pharmaceutical care differs between the inpatient and the ambulatory sector, and between OTC and prescription-only pharmaceuticals (see sections 5.6 Pharmaceutical care and 2.7.4 Regulation and governance of pharmaceuticals). Pharmaceuticals in inpatient care are included in the DRG system, and additional charges (Zusatzentgelte) can be levied in addition to the DRG-based reimbursement only for some expensive drugs. Pharmaceuticals in ambulatory care are provided by pharmacies. The remuneration of pharmacies is regulated in the “Pharmaceutical Price Ordinance for Prescription-only Pharmaceuticals” (AMPreisV), which applies to the entire prescription-only market independent of the source of payment. It applies to human and animal drugs and to community pharmacies, but not to institutional pharmacies or to vaccines, blood replacement and dialysis-related drugs, for which sickness funds negotiate prices with manufacturers. Based on §35 SGB V, the reference price system establishes an upper limit for sickness fund reimbursements (see section 2.7.4 Regulation and governance of pharmaceuticals). The Federal Association of Sickness Funds does the actual setting of reference prices for drugs with the same or similar substances or with comparable efficacy. Reference prices mean that sickness funds only reimburse pharmacies up to a predefined ceiling and patients pay the difference between the reference price and the market price. Pharmaceuticals that are at least 30% below the reference price are exempted from co-payments. For pharmaceuticals with additional benefit, according to the Federal Joint Committee, the Federal Association of Sickness Funds negotiates a reimbursement amount as a discounted price at which the relevant pharmaceutical company has to sell the product.

For prescription-only medicines, the sickness funds pay pharmacists through a flat-rate payment of €8.35 plus €0.21 for the Pharmacy Emergency Service plus a fixed margin of 3% (from the manufacturer’s price). Sickness funds receive a discount (Apothekenabschlag) of €1.77 per dispensed prescription-only drug from the pharmacies, if the sickness funds pay the respective pharmacy within 10 days. The SHI Modernization Act (2004) set cost sharing of prescribed drugs to 10% (minimum €5 (but not exceeding the actual price), maximum €10 per pack). For non-prescription pharmaceuticals, pharmacies can freely determine prices. Exempt from this rule are pharmaceuticals that, in principle, do not require a prescription but for which, for certain indications, physicians may issue prescriptions which will then be paid by the sickness fund. OTC pharmaceuticals are paid out of pocket by individuals, and reimbursement by sickness funds is only possible for children under the age of 12.

3.7.2. Paying health workers

Prices for services provided by physicians, dentists, pharmacists, midwives and other health professionals are set by fee catalogues. Physicians and other health professionals working in hospitals or institutions for nursing care or rehabilitation are paid by salaries. Public and not-for-profit providers usually pay public tariffs, while for-profit providers may pay lower or higher salaries or additional payments. The last pay structure survey conducted by the Federal Statistics Office in 2014 showed that the gross annual pay of a physician in full-time employment was at that time €80 508 on average, including €4114 in the form of additional payments such as Christmas and holiday pay or performance bonuses (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2016). Since then, however, wages for physicians have increased noticeably.