-

30 July 2022 | Country Update

Amendment to the Patients’ Rights Act to reduce waiting times in specialized, outpatient care -

01 June 2022 | Policy Analysis

Entry points for the strategy for the development of primary health care 2022–2031 -

30 September 2021 | Country Update

Final report of the Assessment of EPHOs with WHO Europe published

6.1. Analysis of recent reforms

Table6.1 provides an overview of health care policy initiatives (mostly) from 2016 until July 2021 (time of writing); for information on health reforms prior to 2016, please refer to the previous HiT (Albreht et al., 2016).

Table6.1

Long waiting times are a persistent challenge in the Slovenian health care system, especially in specialized secondary level ambulatory services. They are the only statistically significant factor driving unmet medical need. Over the years, the government has introduced various strategies to address this issue. The most recent, an amendment to the Patients’ Rights Act (2008) in 2022, aims to reduce waiting times through providing additional financing to hospitals and incentives within primary health care. Unusually, funding for these measures would come from the government budget rather than the SHI revenue sources.

Authors

Strengthening primary health care (PHC) has been on the policy agenda in Slovenia for the last decades. In 2016, the process to prepare a PHC strategy was launched. In 2019, the WHO Regional Office for Europe and NIJZ/NIPH conducted an analysis of root causes of challenges in PHC to inform this new strategy. On 26 March 2021, the Ministry of Health (MoH) nominated the Working Group of Primary Health Care Experts, which prepared the document “Entry points for the strategy for the development of primary health care 2022–2031” in dialogue with stakeholders, local representatives, and with professional support from WHO. In autumn 2021, a delegation visited Catalonia to observe their PHC system. The strategy was supported univocally by the Health Council but has not yet been adopted by the National Assembly due to changes of government.

In line with the recent European Strategy for Primary Health Care, the document outlines the following strategic goals:

- Equal access to comprehensive care as close as possible to the population

- Focus on the user and their empowerment

- Comprehensive and integrated treatment

- Quality and safe treatment

- Focus on preventive services

More specifically, it plans changes across several policy areas, including:

Leadership and management

- Outlines establishing an internal structure for PHC with representatives of PHC to strengthen the strategic role of the MoH and a national body for professional support for the development of PHC.

- Plans to define more precisely the roles of other stakeholders for the coordinated development of PHC.

Financing of PHC activities

- Outlines increased public funds for health at the primary level.

- Identifies the introduction of new financing models based on the efficiency and quality of patient treatment for fairer financing of PHC.

- Identifies updating infrastructure and equipment at the primary level.

Provision of human resources and improving working conditions

- Identifies the immediate continuation of existing measures to ensure sufficient personnel resources and appropriate working conditions as a priority.

- To ensure health care access at the primary level for all residents, the strategy identifies (1) updating the network of primary care providers (in the Master Plan of Healthcare Providers) with a needs assessment, (2) introducing rural clinics and (3) improving the care of vulnerable groups through better cooperation between health care providers and local organizations.

- Plans an upgrade of PHC teamwork structures to ensure comprehensive and integrated treatment, including through the expansion of graduate nurse competencies and the establishment of a system of effective cooperation mechanisms between different levels and professional groups.

Digitization and strengthening research to improve quality and safety of care

- Describes the need to further digitalize healthcare through provider and patient e-Health tools like an EHR, tools to support clinical decision-making, and development of data visualizations to support management, quality improvement and governance.

- Outlines the necessity of (1) defining quality indicators for PHC, (2) introducing a system of internal audits and reporting by providers, and (3) establishing a system of monitoring to improving quality and safety at the national level to ensure high-quality and safe medical treatment.

- Prioritizes a user-friendly portal to gather and provide information on the use of health services to empower and involve individuals, including by supporting decision-making when choosing providers.

Certain individual activities are also defined, including the establishment of the tertiary level institute of family medicine.

Authors

References

New pan-European strategy set to transform primary health care across the Region (who.int): https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/13-06-2022-new-pan-european-strategy-set-to-transform-primary-health-care-across-the-region

Albreht T, Polin K, Pribaković Brinovec R, Kuhar M, Poldrugovac M, Ogrin Rehberger P, Prevolnik Rupel V, Vracko P. Slovenia: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 2021; 23(1): pp. i–188.

Integrated, person-centred primary health care produces results: case study from Slovenia. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336184/9789289055284-eng.pdf

Bregant T, Horvat Krstić A, Koprivec J, Ravnikar R, Rotar-Pavlič D, Vračko P. Naj bo primarna raven spet privlačna zdravnikom in dostopna bolnikom. Isis: glasilo Zdravniške zbornice Slovenije. [Tiskana izd.]. Apr. 2022, leto 31, št. 4, str. 21-25, tabele.

Potrjena izhodišča za strategijo razvoja zdravstvene dejavnosti na primarni ravni do leta 2031. Vlada Republike Slovenije. 30 May 2022. https://www.gov.si/novice/2022-05-30-potrjena-izhodisca-za-strategijo-razvoja-zdravstvene-dejavnosti-na-primarni-ravni-do-leta-2031/

From 2017 to 2019, the Ministry of Health and the WHO Regional Office for Europe, together with the NIJZ and over 120 stakeholders and professionals in public health, the community, and other sectors, conducted a comprehensive self-assessment of the WHO Regional Office for Europe’s 10 Essential Public Health Operations (EPHOs) in Slovenia. The final report was published in September 2021, and is intended to support the development of a new national public health strategy. However, the strategy has not yet been developed as major questions around scope and the context and extent of additional financing required are still not answered. A national strategy on public health is necessary at this point, as is a strategy of the National Institute of Public Health.

Authors

References

EPHO self-assessment process in Slovenia (2017 – 2018) | European Journal of Public Health | Oxford Academic (oup.com): https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article/28/suppl_4/cky218.083/5192339

https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289055895

6.1.1. National health care strategy

Based on the results of a 2015 assessment of the Slovene health system performed by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies and the WHO Regional Office for Europe (WHO, 2016), the current National Health Care Plan 2016–2025 – “Together for a society of health” – was designed and confirmed by the Parliament. This strategic Plan sets the vision and objectives for the development of the health system from 2016 to 2025.

6.1.2. Amendments to the principal health legislation

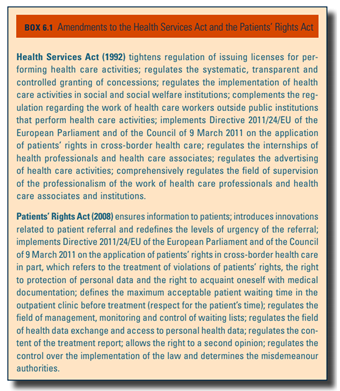

To provide for a legislative basis for the National Health Care Plan 2016–2025, several critical amendments to the Health Services Act (1992) and the Patients’ Rights Act (2008) occurred between 2016 and 2021 (Box6.1). Essential amendments to the Health Care and Health Insurance Act (1992) to ensure financial sustainability of the health system, including diversification of revenue and adjustments to the statutory benefits basket are yet to be prepared.

Box6.1

6.1.3. Public health and preventive care reforms

There have been several reforms in the area of public health, especially to address emerging health issues and within the process of international policy alignment.

Tobacco control

The Restriction of the Use of Tobacco and Related Products Act in 2017 transposed the Tobacco and related products Directive 2014/40/EU of the EU into Slovenian law and introduced other additional measures from the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) (WHO, 2003) including:

- total advertising and sponsorship ban including point of sale displays ban (since 11 March 2018) for all tobacco and related products (e-cigarettes with and without nicotine, herbal products for smoking and novel tobacco products);

- a licensing system for retailers of tobacco and related products (since autumn 2018). In the case of selling to minors or violating advertising ban, the licence is withdrawn, and the fine is €50 000. After the third offence the withdrawal of licence is final with no option to regain (first offence: prohibition of selling for six months; second offence: withdrawal of licence for three years);

- a ban on distance sales (Internet sales) of tobacco and related products;

- a ban on the depiction of smoking or of tobacco and related products on TV shows for minors, except for in films;

- a ban on smoking and using related products in all vehicles (also private cars) in the presence of minors (under 18 years old);

- except for plain packaging, the same scheme as described above (e.g. ban on smoking in all enclosed public places and workplaces, ban on advertising, ban on selling to minors, and a licensing system) applies to tobacco products, e-cigarettes, herbal tobacco for smoking and novel tobacco products (for instance, heated tobacco products); and

- plain packaging for cigarettes and roll-your-own tobacco (mandatory at the retail level since 1 January 2020).

Assessment of Essential Public Health Operations

The MoH, together with the WHO Regional Office for Europe, the NIJZ and over 120 professionals in public health and beyond, conducted a comprehensive self-assessment of the WHO Regional Office for Europe’s 10 EPHOs in 2017–2019. The final report, published in September 2021 (WHO, 2021c), will be used to support the development of a new national public health strategy.

Communicable disease management

All services and treatments related to communicable diseases are fully covered by SHI. In the past five years, and especially in last two due to COVID-19, several reforms have happened in communicable disease prevention and management. Institutional strengthening, including investments in new treatment facilities in the area of noncommunicable diseases are under way, as well as preparation of a proposal of a new Communicable Diseases Act.

Due to significant increases in HIV infection rates, the National Strategy of HIV Prevention and Management 2017–2025 was adopted in 2017, introducing new innovations in prevention, testing and treatment and focuses on systematic education of young people about sexual and reproductive health, among other things. The strategy envisages the preparation and implementation of national guidelines for HIV testing and for the provision of health care for people with sexually transmitted infections.

Changes to existing laws were necessary to combat the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health and health care provision. These were adopted, including to the Communicable Diseases Act (1995).

6.1.4. Primary health care

National primary health care strategy

In 2016, the process to prepare a strategy on primary health care was launched in collaboration with WHO involving all relevant stakeholders. A draft strategy was developed, but not adopted due to the change of the government. In 2019, the WHO Regional Office for Europe and the NIJZ conducted an analysis of root causes of persistent and urgent challenges in the primary health care system to inform further development of the strategy, expected to be finalized in 2021.

Reforms to CPHCs

To strengthen Slovenia’s integrated, person-centred primary health care system, HECs (see section 5.3) in CPHCs are gradually being replaced by HPCs. This recent invention for preventive care and health promotion was developed with support of the Norwegian Financial Mechanism and was first piloted in 2014–2016 (see sections 2.1 and 5.1). Starting with three pilots, there are now 28 HPCs across the country operating within CPHCs. Slovenia was receiving financial support via European Regional Development Fund from 2017 to 2019 to build these additional 25 HPCs (see sections 4.1 and 5.1).

In January 2018, the MoH agreed that all family medicine teams should include 0.5 full-time equivalent of registered nurses, effectively scaling-up the formerly called “family medicine model practices”; they are now called Family Medicine Practices. Not only does this decision aim to strengthen chronic care management and preventive services at the primary health care level – and close to patients’ home – but it also introduces a new human resource standard for family medicine teams.

Additionally, through amendments to the Law on Mental Health (2008) and the National Mental Health Programme 2018–2028, a network of MHCs was introduced. They include the establishment of 25 adults MHCs and 27 MHCs for children and adolescents (see section 5.11).

6.1.5. Chronic care reforms

The Government has adopted several other legislative actions in chronic care, highlighting the increasing concern and burden of chronic diseases within the population (see section 1.4). In 2017, the National Strategy for Dementia Control 2017–2020 was adopted to ensure preventive measures, early detection and an appropriate standard of health care and social protection for people with dementia. A new National Diabetes Management Plan 2020–2030 was also adopted giving strategic direction for the comprehensive and integrated management of the burden of diabetes. To address the growing burden of cancer, an updated Slovene National Cancer Control Plan for 2017–2021 was adopted; a draft of the 2022–2026 Plan is currently in the process of adoption.

6.1.6. Waiting times in ambulatory/outpatient specialist care

Waiting times for specialist referral appointments are an enduring challenge in the Slovene health care system. Several different approaches to improve waiting times have recently been undertaken. In 2017, a governmental project to reduce waiting times and improve the quality of care of services provided in public facilities at all health care levels began (see section 6.1.11 on reforms which were not proposed or experienced implementation setbacks). In 2019, the Government targeted the reduction of the number of patients waiting beyond the maximum established waiting times and an assessment has been started together with the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. The aim was to ensure:

- improvements in the reporting system on waiting lists;

- additional financial resources to tackle incentives for health professionals as well as for the increase in material costs for patients; and

- prioritizing the most hard-hit areas in terms of the number of people waiting and the level of their objective urgency.

Amendments to the Patients’ Rights Act (2008) in 2017 and 2020 were introduced to support these efforts, including redefining the degrees of urgency for referral and deadlines for submitting referrals.

6.1.7. Long-term care

LTC reform has been on the policy agenda since the early 2000s with the aim to streamline the current fragmented and non-transparent services, which are guided by various regulations and funding sources, and to ensure equity in access and solidarity. A new Directorate for LTC was established at the MoH in 2016 to develop, coordinate and implement the LTC Act, originally open to public discussion in 2017. This Act was submitted by the government to the National Assembly in June 2021 and is expected to be adopted by Parliament in late 2021. It introduces a systemic regulation of LTC along with mandatory LTC insurance (to be defined by 2024), sets out eligibility and services structures, recommends improving the working conditions of LTC staff, proposes to co-finance e-care services, raises the level of compensation for out-of-work family carers and introduces the possibility of 21 days of replacement care in institutions to relieve family carers (see sections 2.7, 3.7.1, 5.8 and 6.2).

6.1.8. Digitalization of health care

There have also been considerable advances in e-Health. The Health Databases Act (2000) was amended in 2018 and 2020 to support the introduction of several e-Health solutions; upgrade the IT system; enhance health and health care data collection and management; and expand health registries and databases. The aim is to achieve more population data coverage and enable the linking of national databases. New digital applications include an e-referral system and appointment scheduling system at the secondary and tertiary levels, through a web portal (see sections 2.6 and 4.1.3).

6.1.9. Health system performance assessment (HSPA)

HSPA has been strengthened, particularly in inpatient care. Data collected at the regional and national levels are systematically used to influence national health policy goals. However, HSPA is underdeveloped in other care areas like primary health care. In 2017, the MoH asked NIJZ to start the process of establishing HSPA frameworks and capacities in Slovenia. Initial efforts were co-financed by the European Commission; experts from the University of Malta and the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies provided technical support (see section 7.1). While performance indicators have been defined for all levels of health care, they have not yet been integrated into the system.

6.1.10. Health workforce

Recent reforms to address workforce shortages and large workloads aim to both maintain and increase present staffing levels. The Act on Recognition of Professional Qualifications for Medical Doctors, Specialist Doctors, Doctors of Dental Medicine and Specialist Doctors of Dental Medicine (2010) was amended in 2017 and 2020, and adjusts how professional qualifications of foreign physicians and dentists will be recognized in Slovenia.

6.1.11. Reforms which were not proposed or experienced implementation setbacks

Several reforms were launched but failed, were never formerly proposed or were passed by the government but were never implemented. For example, there were several attempts to change how complementary VHI works – or even to abolish/replace it through SHI. Although some adjustment is needed, especially to change regressive into progressive contributions and to redefine how funds are allocated, the VHI system was confirmed to positively complement the SHI and to be particularly valuable as a compensating mechanism during the financial crisis.

As mentioned in section 4.2.2, in 2017–2018 a project supported by the EU SRSS enabled the development of a methodology that provides a base for planning and forecasting of health professionals based on population needs and demand for health services, as well as taking note of the organizational specifics of the existing health care settings.

Additionally, the 2019 reform of professional competences and activities in nursing care, in which vocationally trained nursing technicians could obtain registered nurse status by fulfilling certain criteria based on experience and by obtaining skills at posts otherwise designated for registered nurses (see sections 4.2.2 and 4.2.6), ended up not being feasible. According to the new regulations, nurse technicians may no longer perform tasks originally within their job descriptions as they now fall under the scope of registered nurses. With insufficient capacities of registered nurses to replace technicians to perform these routine tasks, managers were not able to implement the new reform and still maintain service provision.

Some reforms ran into conflicting impacts of other health care reforms. The 2017 project to shorten the waiting times for secondary level specialist care, for example, ultimately generated longer waiting lists one year later. However, this is a result of several factors. For example, at the time, family medicine physicians collectively decided to continue to refer more complex patients and new methodology for waiting list organization, regulation and monitoring, necessitated a new approach to referring patients (one referral for one medical service, rather than one referral for one medical specialist) that created greater administrative burden for primary care physicians by the ZZZS and an increased overall number of referrals overall.

Due to the large workloads (including administrative burden) faced by family physicians, in 2017–2018, the family physicians’ union pressured the MoH to reduce the required number of patients registered at family medicine practices. This reform was unintentionally undermined by the new referral methodology and additional administrative requirements, resulting in even more red tape.