-

30 July 2022 | Country Update

Amendment to the Patients’ Rights Act to reduce waiting times in specialized, outpatient care

7.2. Accessibility

Slovenia’s centralized SHI system is defined in the Health Care and Health Insurance Act (1992) (see section 3.3.1). More than 99% of residents in Slovenia were covered by SHI in 2019; however, several populations face difficulties in obtaining insurance, including individuals with unclear or changing insurance status, those with unclear residence status, undocumented migrants, the homeless and those with unpaid contributions (Box3.1).

Box3.1

The scope of coverage under SHI in Slovenia is quite broad (see section 3.3.1). The statutory benefits package includes primary, secondary and tertiary services; pharmaceuticals; medical devices; sick leave; and costs of travel to health facilities. There are almost no differences in benefits between the categories of insured people, though some specific benefits do not apply to all categories of insured people (see section 3.3.1). Access to hospitals and specialist outpatient care require referral by a primary care provider, except for medical emergencies. Patient rights are comprehensive and health care is accessible to all, regardless of health or socioeconomic status.

Co-insurance applies to most services and to all patients since 2007 except those specifically listed (see section 3.3.1 and Table3.3), including children under 18, people with disabilities, war veterans, family members of deceased war veterans, and those on low incomes. Social health insurance will cover from 10% to 90% of the cost, depending on the specific type of treatment or activity (see section 3.3.1). A majority of people have complementary VHI to help cover OOP spending on co-insurance, purchased with a flat-rate premium (see sections 3.5, 3.6 and 7.3).

Table3.3

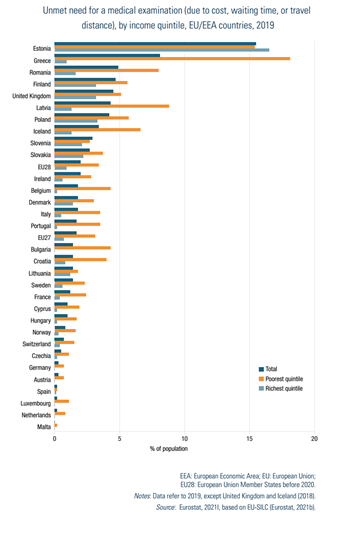

In 2019, according to the Eurostat data based on EU-SILC data, 2.9% of the population expressed an unmet need for medical examination and care, due to cost, distance or waiting time/long waiting lists (Eurostat, 2021k) (Fig7.1).[9] While above the EU average (1.7%), unlike most EU countries, the difference in unmet needs between income groups is negligible, reflecting the near universality of coverage and low rates of OOP spending and catastrophic expenditure (see section 7.3 and Box3.2). Long waiting times are by far the most important factor driving unmet medical needs in Slovenia.

| Fig7.1 | Box3.2 |

|  |

During COVID-19, many services, including all preventive measures, dental services and non-emergency outpatient visits, except oncological and pregnancy related services, were suspended from March to May 2020 to maintain capacity to combat the pandemic. Despite resumption of services, these measures may have increased unmet need. A Eurofound survey found that 24% of Slovenians reported that they had experienced some unmet needs for health care during the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, above the EU average of 21% (Eurofound, 2021).

Unmet needs for dental care are higher than those for medical care, at 3.7% in 2019 (compared with 2.8% in the EU), varying between 4.0% in the lowest income quintile and 3.3% in the highest. As with medical care, these are mainly due to long waiting times; 3.4% of Slovenes reporting this as the main reason. However, the larger discrepancy between income levels reflects relatively limited scope of coverage in dental care and higher accompanying OOP payments.

As waiting times are the main barrier to accessibility of services in Slovenia, especially for secondary level specialist services, they have been a matter of public and political debate for several years and have prompted targeted monitoring and financing incentives to address them. For example, additional funds were made available to increase the volume of some operative procedures with particularly long waiting times and financial stimulations were put in place for increased specialist outpatient visit volumes. It is important to note, however, that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unmet need for medical care of the dynamics between patients and the health system are as yet unknown.

Monitoring is currently based on data gathered from the new, national e-Referrals system (see section 4.1.3). According to these data, on 1 March 2020, i.e. just before the COVID-19 crisis started, 38% of patients were on a waiting list for a first specialist consultation and 33% of those waiting for a diagnostic procedure or treatment were scheduled to wait more than the maximum permissible waiting time (which varies depending on assigned degree of urgency and type of service), though there is considerable variation in reported waiting times depending on the type of service (Breznikar, 2020). While monthly data on waiting times continue to be published, considering the disruption to general health services brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, it will likely take several months to comprehensively evaluate the impact of these disruptions on waiting times.

Primary health care provides access to a wide range of promotive, preventive, diagnostic, curative and rehabilitative health services addressing most of the population’s health needs across the life-course (see section 5.3). The majority of primary care is delivered by a network of 63 CPHCs, owned and managed by municipalities (around 76% of physicians and 42% of dentists working in primary care in 2015). In 2018, just over a quarter of family medicine teams (providing primary care) were represented by independent private concessionaries contracted by the ZZZS (ZZZS, 2020).

There are considerable challenges in ensuring sufficient levels of health care workers in some areas, particularly family medicine specialists and primary care paediatricians. As mentioned in Chapter 4, some rural areas experience difficulties in maintaining the supply of primary care physicians. However, more densely populated urban areas are also affected (Zabukovec, 2020; Human Rights Ombudsman of the Republic of Slovenia, 2020). For example, in April 2021, the webpage of the Ljubljana CPHC, one of the largest in the country, informed users that, due to a lack of capacity, family medicine specialists could not enlist new patients.

- 9. Notably, between 2009 and 2016, Slovenia had one of the lowest reported unmet needs for medical care within the EU, ranging between 0.0% and 0.4% of the population according to Eurostat. However, the rate increased to 3.5% in 2017 before falling to 2.9% in 2019 (Fig. 7.1). This increase is not due to a significant change in access, but rather to adjustments in the survey questions used as a basis to calculate the indicator. ↰

Long waiting times are a persistent challenge in the Slovenian health care system, especially in specialized secondary level ambulatory services. They are the only statistically significant factor driving unmet medical need. Over the years, the government has introduced various strategies to address this issue. The most recent, an amendment to the Patients’ Rights Act (2008) in 2022, aims to reduce waiting times through providing additional financing to hospitals and incentives within primary health care. Unusually, funding for these measures would come from the government budget rather than the SHI revenue sources.