-

13 May 2024 | Country Update

New pharmacist competences and emergency contraception -

28 September 2023 | Policy Analysis

Amendment to the Pharmacy for Pharmacists Act (2017) -

02 December 2022 | Country Update

EU starts an infringement procedure against Poland in relation to the parallel imports of medicines

5.6. Pharmaceutical care

On 1 May 2024, a pilot programme for pharmacist services concerning reproductive health was launched. This initiative allows individuals to access emergency contraception directly from a pharmacist at a pharmacy without the need for a doctor’s consultation. This development stems from the rejection of an amendment to the Pharmaceutical Law by the President, which aimed to make one hormonal contraceptive available without prescription. The pilot programme is scheduled to run until 30 June 2026. Participating pharmacies will provide emergency contraception to individuals aged 15 and above upon presentation of a pharmacy prescription. This age requirement aligns with the legal age of concent in Poland.

At the pharmacy where the pilot programme is underway, discussions with patients will occur in a designated room. This space is equipped with seating for patients. The conversation is led by a pharmacist who is employed at the pharmacy and holds the necessary qualifications to practice pharmacy, including the professional title of Master of Pharmacy.

Even during the consultation stage of the draft regulation, concerns were raised, including by pharmacy and medical self-governing bodies, regarding the dispensing of medicines to minors without parental consent. Both groups expressed uncertainty about the differing rules concerning patient age between doctor’s offices and pharmacies. For instance, while the presence of a legal guardian is necessary during a medical consultation for 15-year-olds, and written consent from both the guardian and the patient is required for individuals aged 16–18, the dispensing of medication by a pharmacist based on a pharmacy prescription does not mandate parental consent or presence. The Ministry of Health argues that the activities conducted under the programme fall outside the scope of health services, pharmaceutical services, or pharmaceuticals.

On 28 September 2023, an amendment to the Pharmaceutical Law Act was introduced to strengthen the provisions of the Pharmacy for Pharmacists Act (2017). The amendment is colloquially referred to as the “Pharmacy for Pharmacists 2.0 amendment” or AdA 2.0.

According to the amendment, only a pharmacist can own a pharmacy. In addition, the pharmacist will not be able to hold shares in companies that control pharmacies and will not be able to establish a chain with more than four pharmacies under competition and consumer protection laws. In addition, a member of the governing body of a company authorized to operate a pharmaceutical wholesaler or a medicinal products intermediary will similarly not be able to take over an entity running a retail pharmacy. Finally, if an unauthorized person (that is, non-pharmacist) takes over a pharmacy or pharmacy chain, the pharmaceutical inspector can revoke their authorization and prevent them from doing so.

The aim of these regulations is to prevent entities operating as pharmacy chains or franchises from taking over companies operating pharmacies. The Pharmacy for the Pharmacist Act introduced in 2017 made it impossible for those entities to open new pharmacies. As a result, they began to increase their market shares by taking over and buying smaller pharmacies. AdA 2.0 contains provisions to close this loophole. It also gives the pharmaceutical inspectorate the right to revoke licenses and impose a fine of up to PLN 2 million on entities that violate these regulations.

Although AdA 2.0 only refers to the pharmacy retail market, it also introduces changes for pharmaceutical wholesalers. Moreover, it contains a range of sanctions for violating the regulations it introduces. These include both financial penalties and administrative sanctions such as the withdrawal of the license to operate a pharmacy.

The amendment also includes a provision that reduces the frequency of pharmaceutical inspections in wholesalers and entities that operate wholesalers. Currently, such inspections must be carried out every three years. According to the new regulation, the Chief Pharmaceutical Inspectorate will repeat inspections every five years. Some pharmacists view this is as a purely formal and long-awaited change. It results from the insufficient resources of the Chief Pharmaceutical Inspectorate to inspect wholesalers.

On 29 September 2022, the European Commission launched an infringement procedure against Poland for failing to comply with the EU rules on the free movement of goods in relation to the parallel imports of medicines, which is allowed within the EU.

The Commission claims that Poland prohibits parallel import of generics when the previously authorized medicinal product is a non-generic. In the opinion of the Commission, this prohibition is inconsistent with Art. 34 and Art. 36 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The Polish government has two months to address these concerns.

This is not the first time that the EC initiated infringement proceedings against Poland in relation to the parallel trade in medicines. For example, in 2018, the EC closed the then ongoing proceedings against Poland on the grounds that parallel trade led to shortages of essential medicines in Poland.

Authors

5.6.1. Manufacturing and distribution

Poland has a long-standing tradition of manufacturing medicines. In February 2018, 223 manufacturers and importers of medicinal products and 142 producers, importers and distributors of active product ingredients were listed in the registers of the Chief Pharmaceutical Inspector (GIF, 2018a). The pharmaceutical market is dominated by foreign pharmaceutical firms – in 2016, among the 50 companies that accounted for the largest share of NFZ’s expenditure on pharmaceuticals, only 11 had (majority) Polish capital and only nine had manufacturing facilities in Poland (MZ, 2018c). Since the 1990s, the Polish pharmaceutical market has been characterized by a high trade deficit. In 2016, pharmaceutical exports amounted to PLN 11.7 billion while imports amounted to PLN 22.3 billion. Over 70% of exports and 82% of imports were to or from the EU (MZ, 2018c).

Pharmaceutical manufacturing and distribution are almost fully privatized. In 2016, only three entities were still supervised by the Minister of Treasury: one pharmaceutical wholesaler (Cefarm), one manufacturer of vaccines and sera (Biomed), and one pharmaceutical manufacturer and wholesaler focusing on the generics market (Polfa) (Sejm/rynekaptek.pl, 2016).

Medicines can be sold or dispensed to the public through several types of retail outlets:

- pharmacies: (1) outpatient pharmacies; (2) hospital pharmacies – dispensing medicines to hospitalized patients only; and (3) dispensaries not for general public, operating in health care units under jurisdictions of the Ministry of National Defence or the Ministry of Justice (e.g. in penitentiary institutions);

- pharmacy outlets: usually operating in rural areas and offering a limited assortment of medicines; and

- “non-pharmacy trade outlets”: (1) herbal medical stores; (2) specialty shops selling medical supplies; and (3) general stores (e.g. grocery stores, petrol stations).

At the end of 2017 there were 13 363 outpatient pharmacies, almost all of them privately owned, 24 dispensaries not for general public and 1284 pharmacy outlets. Internet sale of medicinal products (which is allowed for OTC products only; see section 2.4.4) was performed by 280 pharmacies and four pharmacy outlets (GUS, 2018b; GUS, 2019). Independent pharmacies dominate among outpatient pharmacies (56.9% of the total number; 41.1% of the total value of sales) but the importance of network pharmacies (with five or more pharmacies belonging to the same network) has been increasing both in terms of their number and total value of sales (IQVIA, 2018).

The mail order and Internet sale (via e-pharmacies) of pharmaceuticals have been increasing. In 2017, the total value of these sales (retail prices) exceeded PLN 466 million and the market grew by 20.5% compared with the previous year. Vitamins and minerals dominated these sales (15.9% of the value), followed by milk products for children (11.6%), cosmetics for women (8.8%), digestion and digestive system products (6.9%), flu and respiratory system products (6.7%) and other categories (IQVIA, 2018).

5.6.2. Consumption

According to the 2001 Act on the Pharmaceutical Law, four types of prescriptions may be issued:

- Rp (or Rx) – medicines dispensed with physician’s prescription;

- Rpz – medicines dispensed with physician’s prescription for restricted use;

- Rpw – medicines dispensed with physician’s prescription and containing certain narcotic or psychotropic substances; and

- Lz – medicines used in hospital settings.

The number of products available to the general public has been increasing in recent years and many products that were formerly available only in pharmacies can now be purchased in general stores. The share of OTC pharmaceuticals and food supplements has been growing as a share of the total volume of pharmaceutical market. OTC medicines and other products available without prescription in outpatient pharmacies (such as dietary supplements and cosmetics) account for 35.3% of the pharmaceutical market (2017 sales data; IQVIA, 2018). They are followed by sales of prescription-only (Rx) reimbursed medicines sold in outpatient pharmacies (32.3%), and Rx non-reimbursed medicines sold in outpatient pharmacies (15.7%), hospital sales (15.5%) and mail order (including Internet) sales (1.2%) (IQVIA, 2018).

5.6.3. Accessibility, adequacy and quality of pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical care

The network of outpatient pharmacies is well developed and is among the densest in Europe. In 2017, there were on average 2665 inhabitants per outpatient pharmacy or pharmacy outlet, compared with 3214 inhabitants on average in the EU (PGEU, 2018). In rural areas, there were on average 7114 inhabitants per outpatient pharmacy in 2017. The average number for Poland is 2876 (GUS, 2019). The night duties were fulfilled permanently by 2.9% and temporarily by 21.7% of outpatient pharmacies (GUS, 2017b).

According to the official list maintained by the President of the URPLWMiPB, in March 2017 there were 10 220 medicinal products authorized for trade on the territory of Poland by the URPLWMiPB, 2339 medicinal products authorized for trade through approvals issued by the Council of the European Union or the EC, and 3640 medicinal products authorized for trade through a parallel import licence, with the role of parallel imports growing in recent years (URPLWMiPB, 2018). Based on these numbers, one can say that the accessibility of medicines in Poland is similar to other countries in the EU. However, actual accessibility is limited by parallel exports[18] of drugs reimbursed in Poland to other countries in the EU and a high degree of cost-sharing. Poland is one of the major parallel exporters of medicines among the EU Member States. This also concerns parallel export of reimbursed pharmaceuticals, the so-called “reverse chain of drug distribution”, which is illegal and has been one of reasons for shortages of medicines on the Polish market in recent years (Kawalec, Kowalska-Bobko & Mokrzycka, 2015).

Per capita expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals in Poland is one of the lowest among the OECD countries: in 2015 it amounted to EU and a high degree of cost-sharing. Poland is one of the major parallel exporters of medicines among the EU Member States. This also concerns parallel export of reimbursed pharmaceuticals, the so-called “reverse chain of drug distribution”, which is illegal and has been one of reasons for shortages of medicines on the Polish market in recent years (Kawalec, Kowalska-Bobko & Mokrzycka, 2015).

Per capita expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals in Poland is one of the lowest among the OECD countries: in 2015 it amounted to $352 PPP in Poland compared with the average of $553 PPP for 31 OECD countries (OECD, 2017). However, a high share of this expenditure has to be covered by patients out of their own pockets. Cost-sharing is widely applied to outpatient pharmaceuticals and OOP spending on drugs is very high – for retail pharmaceuticals it amounts to 66% of total expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals (see sections 3.2 and 3.4).

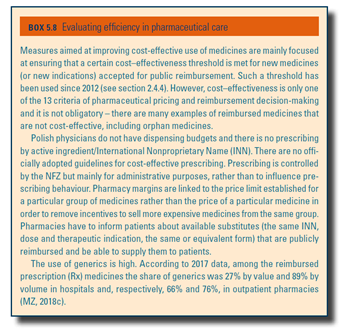

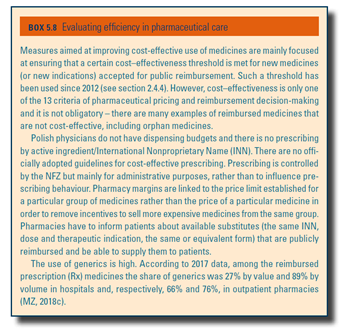

In January 2018, 4261 medicines were included in the reimbursement list and were available to patients free of charge or with a co-payment (flat rate co-payment or co-insurance of 30% or 50%) – up to an appropriate reimbursement limit (see section 3.4.1). Expensive medicines, usually new and innovative, can be covered within special medication programmes and are available free of charge to patients covered by these programmes. In January 2018, 397 medicines with distinct EAN codes were included in such programmes. A further 466 medicines were available free of charge within chemotherapy programmes. Finally, since 2016, people aged 75+ are exempted from paying for certain medicines – 1657 products as of January 2018. Efficiency in pharmaceutical care is evaluated in Box5.8.

Box5.8

nbsp;352 PPP in Poland compared with the average of EU and a high degree of cost-sharing. Poland is one of the major parallel exporters of medicines among the EU

Member States. This also concerns parallel export of reimbursed

pharmaceuticals, the so-called “reverse chain of drug distribution”,

which is illegal and has been one of reasons for shortages of medicines

on the Polish market in recent years (Kawalec, Kowalska-Bobko &

Mokrzycka, 2015).

nbsp;352 PPP in Poland compared with the average of EU and a high degree of cost-sharing. Poland is one of the major parallel exporters of medicines among the EU

Member States. This also concerns parallel export of reimbursed

pharmaceuticals, the so-called “reverse chain of drug distribution”,

which is illegal and has been one of reasons for shortages of medicines

on the Polish market in recent years (Kawalec, Kowalska-Bobko &

Mokrzycka, 2015).

Per capita expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals in Poland is one of the lowest among the OECD countries: in 2015 it amounted to $352 PPP in Poland compared with the average of $553 PPP for 31 OECD countries (OECD, 2017). However, a high share of this expenditure has to be covered by patients out of their own pockets. Cost-sharing is widely applied to outpatient pharmaceuticals and OOP spending on drugs is very high – for retail pharmaceuticals it amounts to 66% of total expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals (see sections 3.2 and 3.4).

In January 2018, 4261 medicines were included in the reimbursement list and were available to patients free of charge or with a co-payment (flat rate co-payment or co-insurance of 30% or 50%) – up to an appropriate reimbursement limit (see section 3.4.1). Expensive medicines, usually new and innovative, can be covered within special medication programmes and are available free of charge to patients covered by these programmes. In January 2018, 397 medicines with distinct EAN codes were included in such programmes. A further 466 medicines were available free of charge within chemotherapy programmes. Finally, since 2016, people aged 75+ are exempted from paying for certain medicines – 1657 products as of January 2018. Efficiency in pharmaceutical care is evaluated in Box5.8.

Box5.8

nbsp;553 PPP for 31 OECD countries (OECD,

2017). However, a high share of this expenditure has to be covered by

patients out of their own pockets. Cost-sharing is widely applied to

outpatient pharmaceuticals and OOP

spending on drugs is very high – for retail pharmaceuticals it amounts

to 66% of total expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals (see sections 3.2

and 3.4).

nbsp;553 PPP for 31 OECD countries (OECD,

2017). However, a high share of this expenditure has to be covered by

patients out of their own pockets. Cost-sharing is widely applied to

outpatient pharmaceuticals and OOP

spending on drugs is very high – for retail pharmaceuticals it amounts

to 66% of total expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals (see sections 3.2

and 3.4).

In January 2018, 4261 medicines were included in the reimbursement list and were available to patients free of charge or with a co-payment (flat rate co-payment or co-insurance of 30% or 50%) – up to an appropriate reimbursement limit (see section 3.4.1). Expensive medicines, usually new and innovative, can be covered within special medication programmes and are available free of charge to patients covered by these programmes. In January 2018, 397 medicines with distinct EAN codes were included in such programmes. A further 466 medicines were available free of charge within chemotherapy programmes. Finally, since 2016, people aged 75+ are exempted from paying for certain medicines – 1657 products as of January 2018. Efficiency in pharmaceutical care is evaluated in Box5.8.

Box5.8

- 18. Parallel imports/exports refer to cross-border sales of goods by independent traders outside the manufacturer’s distribution system without the manufacturer’s consent. Parallel traders generate profit by buying goods in one EU Member State at a relatively low price and subsequently reselling them in another Member State where the price is higher. ↰