-

14 February 2025 | Policy Analysis

Estonian government approved Hospital Network Development Directions 2040 -

10 February 2025 | Country Update

Estonia centralizes and standardizes ischemic stroke care in the nationwide patient pathway

5.4. Specialized care

In December 2024, the Estonian government approved the Hospital Network Development Directions 2040, which were developed over the period of 2020–2022. The plan outlines the future structure of the hospital system, defining the network organization, hospital responsibilities, principles for cooperation and consolidation, and an investment roadmap.

The main aim of the plan is to ensure high-quality, accessible specialized medical services that take into account changing demographics and future trends in both the health sector and society at large. Each county will retain at least one hospital providing 24/7 emergency and specialized care, although the overall hospital network will be reduced from 20 to 17 facilities. This reduction will be achieved by merging four hospitals in Tallinn into a single unified institution, Tallinn Haigla.

A core principle of the plan is to centralize high-tech, resource-intensive services, while decentralizing frequently needed services such as mental health, nursing and palliative care across all counties. The plan also aims to integrate health and social care services to provide more comprehensive care, particularly for older people and those with chronic conditions. To achieve that, it emphasizes the establishment of local service networks that bridge hospital-based specialist care with primary care, ambulance services and social services, aiming to reduce fragmentation of services and improve continuity of care.

Based on the plan, hospitals will also be required to adopt sustainable practices to minimize their impact on the environment and climate by using renewable energy, improving waste management and promoting circular economy principles. The plan also envisions strengthening the role of the state in governing the hospital network, although it does not specify how this should be achieved.

Another critical aspect of the plan is crisis preparedness. Hospitals must ensure continuity of operations during both civil and military crises by establishing formal frameworks for cooperation with military organizations and regional partners involved. This includes defining clear chains of command, partner roles, crisis management procedures, and flexible patient transfer mechanisms to maintain essential care during emergencies.

The overall investment needs for hospital infrastructure are estimated at EUR 1.8 billion by 2040. However, no direct funding has been allocated in the current state budget. If investment funds become available, priority will be given to enhancing psychiatric services and developing Tallinn Haigla.

Authors

References

Starting from 1 January 2025, a nationwide ischemic stroke care pathway was implemented in Estonia. It standardizes stroke patient management and provides role-specific guidelines, including for stroke nurses, coordinators and family physicians [1].

The pathway was designed based on findings from a 2019–2022 pilot project, which demonstrated significant value in ensuring a seamless care process for stroke patients [2]. Initiated by the Estonian Health Insurance Fund (EHIF), project identified key issues such as fragmented post-stroke care, insufficient rehabilitation services, poor information flow and a lack of financial incentives for integrated care, which were addressed in the implemented standards.

The updated pathway aims to unify care practices, ensuring smoother patient transitions between treatment stages. It was developed in collaboration with specialists, quality managers and patient representatives.

Stroke care in Estonia is now centralized in six designated hospitals, with a new role, the stroke pathway coordinator, been introduced. This coordinator is responsible for assessing patient needs, creating individualized treatment plans, monitoring their implementation, and coordinating healthcare, social and community services. The monitoring indicators were also integrated into provider contracts to ensure quality and accountability. Throughout 2025, data will be analyzed to identify which indicators would be used for developing performance-based payment models.

Authors

5.4.1. Specialized ambulatory care

Specialized care in Estonia is provided in hospitals and outpatient centres. The majority of specialized ambulatory care is provided in hospital outpatient departments, with the remainder delivered by health centres or independent specialists.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the EHIF started financing remote specialist consultations. In mid-July 2020, it formally added remote consultations to the list of health care services. Offering this option in specialist care can increase patient care compliance and outcomes, improve accessibility and reduce co-payments. Nevertheless, an administrative consultation which has no clinical substance cannot be billed as a remote consultation (for example, scheduling appointments, re-prescribing medications). Furthermore, the remote consultations are only allowed for follow-up visits, which means that in most cases hospitals are not eligible for a patient visit fee. Visit fees apply when a family physician refers a patient directly to a hospital midwife or nurse. The EHIF has defined a list of criteria for remote consultations. Providers are reimbursed at the same level for remote consultation as for an on-site visit (see section 3.7.1 Paying for health services).

From 1 January 2021, digital consultations in specialized ambulatory care with multiple specialists were added to the list of health care services, aiming to initiate and empower interdisciplinary consultations, which could improve continuity of care and access to services. The new e-consultation service facilitates the patient’s clinical pathway and improves access, by eliminating the need to travel to see multiple doctors at once. The service uses the direct contact and secure communication technology solution provided through the ENHIS. The criteria for the provision of e-consultation are in line with the requirements for e-consultation between the patient, family physicians or other specialists, which were introduced in mid-July 2020 (see sections 3.7.1 Paying for health services and 6.1.6 Efforts to improve care coordination and person-centredness).

In addition, in 2018, the MoSA, in cooperation with the Association of Neurologists and the EHIF, launched an initiative to develop integrated care pathways for stroke patients to improve the disease management and integration between different care providers and settings (see Box5.2). In 2021, the EHIF began the development of funding for the hip and knee replacement care pathway, and the testing period for the use of this pathway runs from April 2023. In addition, a treatment pathway focusing on mental health is being developed (EHIF, 2021b) (see section 3.7.1 Paying for health services).

Box5.2

5.4.2. Day care

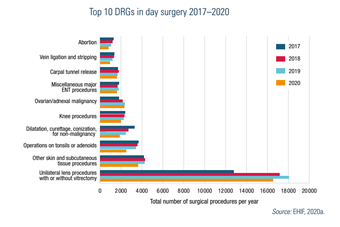

The concept of day care covers the elective procedures where patients come to a hospital or day care unit and return home the same day without staying overnight. Hospitals and ambulatory care providers with a day care licence issued by the Health Board provide day care services. Improvements in surgical techniques and technology have widened the range of procedures suitable for day care. Ophthalmology is the most advanced in day surgery, with 99% of cataract operations performed in a day care setting (EHIF, 2020b). Other specialties, such as gynaecology, otorhinolaryngology, orthopaedics and vascular surgery etc., also perform day surgery activities. Fig5.2 shows the number of day surgery cases by DRG from 2017 to 2020, with a decrease in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of elective surgery.

Fig5.2

In addition to surgical procedures, day care also includes some non-surgical procedures such as haemodialysis, chemotherapy and other therapies and different diagnostic procedures.

Day care is mainly financed through contracts with the EHIF. In some areas, providers have established private practices and are not contracted by the EHIF, so their services need to be paid out of pocket by patients or by private insurance. The development of day care and day surgery has been stimulated since 2002 through separation of day care funding from ambulatory and hospital funding (see sections 3.7.1 Paying for health services and 7.6 Health system efficiency).

5.4.3. Inpatient care

The hospital sector in Estonia is dominated by public hospitals, which are divided into regional, central, general, local, special and rehabilitation care hospitals depending on the catchment area, the services provided and/or the location of the hospital (see section 4.1 Physical resources). The geographical location of hospitals ensures that the treatment is available to everyone within 70 km or a 60-minute drive (see Box4.1). Each type of hospital fulfils special requirements established by the MoSA, such as the list and scope of services to be provided and standards for the rooms, medical equipment and medical staff.

Box4.1

Regional hospitals provide a full range of health care services. Central hospitals deliver most services, although some services, such as cardiac surgery, neurosurgery and certain oncological services, are excluded. General hospitals provide 24-hour emergency care as well as intensive care and some surgical and medical specialties. Local hospitals deliver 24-hour doctor-based emergency care but no surgeries.

The relationship between the health care providers and the EHIF is based on contracts, and both public and private providers can hold contracts with the EHIF. The EHIF is allowed to selectively contract providers, but has to contract all HNDP hospitals (see section 3.3.4 Purchasing and purchaser–provider relations).

Requirements for accessibility of care are established by the MoSA. The EHIF Supervisory Board revises the waiting time targets for all types of care. At early 2023, the maximum waiting times for ambulatory specialized care were six weeks and eight months for inpatient care and day surgeries, respectively. Some interventions have longer maximum waiting times: for example, a year and a half for cataract surgery, large-joint endoprostheses and bariatric surgery (see section 7.2 Accessibility).

In 2018, the EHIF updated the principles of geographical availability for the annual contract planning with the aim of ensuring equal access to high-quality medical care, regardless of place of residence (EHIF, 2018). The criteria define a minimum number of services at the county level for specialist outpatient care, followed by day and inpatient care, to avoid fragmentation of working hours in different locations. There are four levels of access, ranging from rare and complex care (the first level, which is available in Tallinn or Tartu, for example organ transplantation) to common care (the fourth level, which is accessible at the county level, for example general surgery, otorhinolaryngology, ophthalmology, gynaecology, dermatovenerology and psychiatry). These criteria guide the provider selection process and are partly followed in the contracting of HNDP hospitals.

The Health Board monitors the quality of health care services. In addition, the EHIF regularly conducts clinical audits and randomized inspections of service provision to assess compliance with relevant legislation, clinical guidelines and best practice. Since 2013, various quality-monitoring indicators have been developed and used to assess the quality of care in cooperation with the EHIF and the Medical Faculty of the University of Tartu, which have jointly established the Board for Quality Indicators. At the time of writing (early 2023), there is a list of indicators for 10 medical specialties (including ambulance services). Most indicators are updated annually and published on the EHIF webpage (see sections 2.2.1 The role of the state and its agencies and 7.4 Health care quality).