-

14 February 2025 | Policy Analysis

Estonian government approved Hospital Network Development Directions 2040 -

04 June 2024 | Policy Analysis

Assessment of pharmacy reform and current situation in the pharmaceutical sector

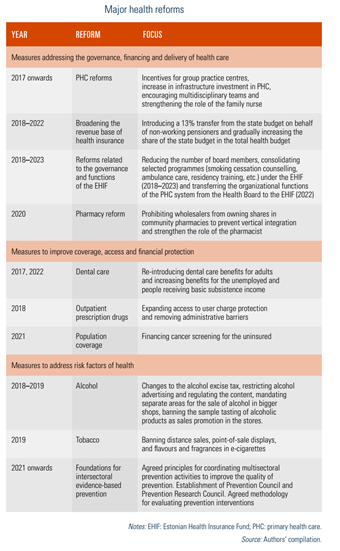

6.1. Analysis of recent reforms

Since 2017, recent changes in the Estonian health care system have focused on improving the efficiency and the sustainability of its financing. Over the past decade, the mandate of the EHIF has been expanded in terms of functions and responsibilities. Its revenue base has also been diversified through increasing transfers from the state budget on behalf of non-working pensioners.

Steps have also been taken to improve financial protection, such as extending protection from user charges for medicines and increasing dental care benefits for low-income individuals. Efforts are being made to strengthen PHC and care integration, including improvements in information systems, development of patient pathways and the expansion of e-health services.

Table6.1 provides an overview of recent health reforms from 2017 to 2022, which are described in greater detail below. For more information on past measures, see Habicht et al. (2018).

Table6.1

In December 2024, the Estonian government approved the Hospital Network Development Directions 2040, which were developed over the period of 2020–2022. The plan outlines the future structure of the hospital system, defining the network organization, hospital responsibilities, principles for cooperation and consolidation, and an investment roadmap.

The main aim of the plan is to ensure high-quality, accessible specialized medical services that take into account changing demographics and future trends in both the health sector and society at large. Each county will retain at least one hospital providing 24/7 emergency and specialized care, although the overall hospital network will be reduced from 20 to 17 facilities. This reduction will be achieved by merging four hospitals in Tallinn into a single unified institution, Tallinn Haigla.

A core principle of the plan is to centralize high-tech, resource-intensive services, while decentralizing frequently needed services such as mental health, nursing and palliative care across all counties. The plan also aims to integrate health and social care services to provide more comprehensive care, particularly for older people and those with chronic conditions. To achieve that, it emphasizes the establishment of local service networks that bridge hospital-based specialist care with primary care, ambulance services and social services, aiming to reduce fragmentation of services and improve continuity of care.

Based on the plan, hospitals will also be required to adopt sustainable practices to minimize their impact on the environment and climate by using renewable energy, improving waste management and promoting circular economy principles. The plan also envisions strengthening the role of the state in governing the hospital network, although it does not specify how this should be achieved.

Another critical aspect of the plan is crisis preparedness. Hospitals must ensure continuity of operations during both civil and military crises by establishing formal frameworks for cooperation with military organizations and regional partners involved. This includes defining clear chains of command, partner roles, crisis management procedures, and flexible patient transfer mechanisms to maintain essential care during emergencies.

The overall investment needs for hospital infrastructure are estimated at EUR 1.8 billion by 2040. However, no direct funding has been allocated in the current state budget. If investment funds become available, priority will be given to enhancing psychiatric services and developing Tallinn Haigla.

Authors

References

The pharmacy reform in Estonia was implemented on 1 April 2020, following a five-year transition period. Its objective was to prioritize professional development in the pharmacy market and strengthen the role of the pharmacists in the health system by allowing them to control capital of a general pharmacy. Previously, owners of wholesale distribution licenses for medicines were permitted to hold shares in pharmacies. Thus, the reform aimed to break the vertical integration between wholesale and retail pharmacies by changing the ownership rules. This allowed pharmacists to own pharmacies rather than wholesalers. The Competition Authority recently conducted an analysis to assess the impact of three-year-old reform. The focus was on the competitive landscape and the independence of pharmacies post-reform, examining both enabling and constraining factors. As part of the analysis, the Competition Authority surveyed 42 pharmacies (about 9% of all pharmacies).

The analysis results show that the pharmacy reform has not achieved its intended goal. While pharmacists now own pharmacies, these establishments remain connected to their former wholesale owners through supply, franchise, underlease, and other agreements. In addition, some pharmacies operate in premises within hospitals or shopping centres rented from companies or franchisors linked to wholesale distributors, limiting their independence. The Competition Authority has suggested additional measures to address this issue, particularly where the right to use commercial space should be controlled solely by the franchisor.

In addition, the Competition Authority discovered that there has been no new competition on the pharmaceutical wholesale market over the same period of time. Moreover, during the last years, the wholesale sector saw even greater consolidation of competition as the market shares of the two major wholesale traders have increased. Together, they now own more than 80% of the market.

In addition, the Competition Authority has previously expressed the view that the existing model of price regulation for medicines does not work. Although the prices of medicines are agreed between the manufacturer and the state, and wholesale and retail mark-ups are regulated, the manufacturers give wholesale traders significant discounts on the nationally agreed price. To ensure that manufacturers’ discounts to wholesale traders reach the retail level and from there the consumers, the Competition Authority suggested developing effective regulation and implement measures to stimulate price competition between wholesale traders. Nevertheless, there were no changes in this regard during the reform.

Furthermore, the Competition Authority’s analysis proposed introducing additional requirements for pharmacy ordering systems to promote equal access for all wholesale traders. It also suggested establishing a system that automatically selects the cheapest supplier or the best offer based on relevant criteria like delivery time. Such approach would motivate wholesale traders to engage in competition more actively.

Authors

References

The Competition Authority https://www.konkurentsiamet.ee/en/news/pharmacy-reform-has-not-increased-competition-pharmaceutical-sales-market

Full analysis (in Estonian) https://www.konkurentsiamet.ee/media/583/download