-

01 May 2023 | Policy Analysis

New Health System Reform Strategy for Slovenia

4.1. Physical resources

4.1.1. Infrastructure, capital stock and investments

Infrastructure

There were 413 beds in acute hospitals per 100 000 inhabitants in Slovenia in 2019. While this is substantially fewer than in Austria, for example, Slovenia has more beds in acute hospitals than the EU average, Estonia, Finland or Sweden (Fig4.1).

Fig4.1

The total number of hospital beds has decreased since the 1980s – from 695 per 100 000 population in 1980 to 443 per 100 000 in 2019 (NIJZ, 2020b; WHO, 2015b). Since 2009, there has been only a 4% decrease, suggesting a slowing trend. When differentiating between bed types, since 1990, acute care bed numbers have decreased (by 37%), representing 79% of total hospital beds in 2019. There are also 18% fewer psychiatric beds since 1990; psychiatric beds now represent 15% of all beds. Conversely, LTC beds in hospitals, introduced in the early 2000s as non-acute care, have increased, accounting for 3% of all hospital beds in 2019 (Table4.1), enabling a smoother transition of hospitalized patients to other non-hospital care settings (e.g. rehabilitation in spas, home care or homes for the elderly).

Table4.1

Continuous development of health technologies and changes to hospital reimbursement, for example, a shift from bed-day payments to case-based (DRG) payments, shortened the total average length of stay in hospital for inpatients from 11.4 in 1990 to 7.1 days in 2018 (NIJZ, 2019; Eurostat, 2021f). The average length of stay in acute care only decreased slightly, from 6.8 days in 2011 to 6.7 in 2018 (see section 5.4.3) (Eurostat, 2021d).

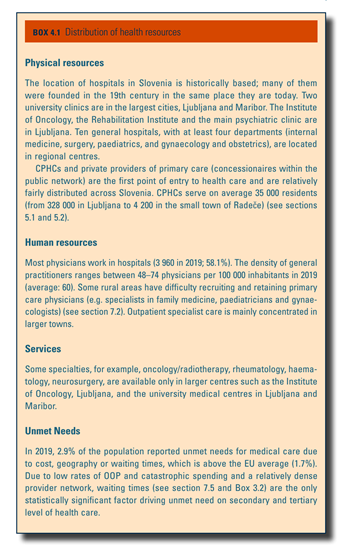

Current capital stock

In 2019, there were a total of 27 public, state-owned (non-profit) hospitals in Slovenia, including 10 general (regional) hospitals, two university hospitals, one oncological institute, one rehabilitation institute, five psychiatric hospitals, three hospitals for pulmonary diseases, one orthopaedic hospital, two gynaecological and obstetrics hospitals, and two sanatoria for children. Three private hospitals provide for cardiovascular surgery, general surgery and a diagnostic centre. Seven additional private providers, who rent facilities, equipment and nursing staff in public hospitals, deliver acute hospital care as day care or inpatient care (ZZZS, 2015). Private providers operate as for-profit organizations. In addition to the 27 public hospitals, there are 63 municipality-owned CPHCs (see sections 2.1, 5.1 and 5.3) and three public health care institutions: the Blood Transfusion Centre of Slovenia, NIJZ and NLZOH. Box4.1 describes the geographical distribution of health resources in Slovenia.

Box4.1

The three private hospitals represent only 1% of all inpatient beds in Slovenia. The largest hospitals, University Medical Centre Ljubljana and University Medical Centre Maribor, have 2138 and 1266 beds, respectively. General hospitals average 330 beds (130–720); the six smallest hospitals average 50 beds (25–85).

Regulation of capital investment

Capital investment allocations for public health care institutions are proposed by the MoH’s Investments and Public Procurement Unit and set by its Committee on Investments. Overall responsibility for the planning of infrastructure and capital investments in public facilities lies with the respective owners – the MoH for hospitals and other secondary care infrastructure and local (municipal) governments for public primary health care facilities and public pharmacies.

There is no national strategic document on the future development of hospitals; Slovenia continuously invests in construction, extension and refurbishment of health facilities, especially hospital buildings, including, most recently, General Hospital Slovenj Gradec, General Hospital Novo Mesto and General Hospital Brežice.

Investment funding

The MoH invests in hospitals and other secondary care infrastructure at the national and regional levels, while local governments at the municipal level are responsible for capital investments in public primary health care facilities and public pharmacies. Slovenia has also received support from the EU: during the period 2017–2019, European Regional Development Fund helped build 11 emergency centres in hospitals (see section 5.5) and 25 health promotion centres (HPCs) within CPHCs (for a current total of 28; see section 5.1).

At the national and regional levels, capital investment funding is performed exclusively through a special allocation in the national budget and managed by the MoH. The volume of the government budget to capital investments is informed by suggestions from the leadership of the public provider institutions. Neither the MoH nor the ZZZS is liable to compensate for hospitals’ deficits, whether these are overruns in the capital funds to build new facilities or deficits incurred once the facility is operational; these are generally the responsibility of the respective provider. Municipalities raise their own revenue for capital investments, though financially disadvantaged municipalities with lower development levels receive assistance from the national budget.

Ongoing funding of capital and maintenance costs is covered through reimbursement for service delivery, though these costs are often underestimated in services’ prices.

Capital investment in private practices is self-funded by providers, regardless of a contractual relationship with the ZZZS.

4.1.2. Medical equipment

Equipment financing

Investment in medical equipment is the responsibility of the owner of the particular health care facility. All public tenders for major pieces of medical technology, such as positron emission tomography (PET), MRI and CT equipment, in state-owned providers are prepared and conducted by the MoH. National funds within its budget are set aside for these investments. All other investments in medical equipment are funded by providers themselves from revenue earned.

For new technologies, the Health Council at the MoH approves costs, scientific justification and the economic sustainability of the proposed programme, in line with national priorities. In 2003, the MoH and the ZZZS centralized the procedure for purchasing medical equipment, devices and aids to increase transparency of public spending and reduce prices, consequently allowing for equitable geographical distribution of equipment, devices and aids.

There is no estimation of national medical equipment need or a national plan on such investments. Information on regulation of medical devices and aids can be found in section 2.7.5.

Equipment infrastructure

The availability of medical equipment is below the average of EU27 countries for which data are available (Table4.2). MRI units and CT scanners are stationed in hospitals and in specialized ambulatory care. PET scans are only found in hospitals. Primary health care offers some diagnostic and imaging tools (e.g. radiology and ultrasound devices).

Table4.2

A registry of radiation sources in medicine and veterinary services developed at the Slovene Radiation Protection Administration is the only relevant source of data on available radiation devices in Slovenia. This institution is not competent to supervise non-ionizing techniques, such as MRI.

4.1.3. Information technology and e-Health

Digitalization of the health care system

In the last five years, the Slovene health care system has undergone a digital transformation, in line with national and European strategies, and WHO guidelines for improving the quality and efficiency of health care systems. New e-Health solutions are intended to streamline existing fragmented hospital and outpatient information systems to improve care coordination, enable secure exchange of data and facilitation of communication between providers and increase the availability of medical, economic and administrative data for research purposes (Stanimirović & Matetić, 2020) (see section 2.6).

The system has already resulted in long-term reductions in administrative costs and facilitated more efficient management of health-related data and information (Ministry of Public Administration, 2019).

The basis for this transformation has been the e-Health (e-Zdravje) Project, funded through EU cohesion funds and led by the MoH between 2008 and 2015 (see section 2.6). In December 2015, NIJZ assumed the management of e-Health for the country. Slovenia’s e-Health implementation success, despite initial challenges, has been recognized by national and international authorities, including the Ministry of Public Administration and the European Commission in 2019. It was also placed sixth in e-Health Services for 2019 in the Digital Economy and Society Index Report.

Currently, there is no valid long-term national e-Health strategy; all planning and development activities are based on operative short-term plans of the NIJZ, adopted annually by the MoH. In April 2021, the government appointed a new committee for digitalization, whose tasks include delivering a new e-Health strategy. E-Health services are available to all health care providers and patients in Slovenia. All state- or municipality-owned providers are fully using e-Health solutions, as well as the great majority of private providers within public funding scheme.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised awareness and increased usage of e-Health solutions (e.g. e-prescriptions, e-referrals and teleconsultations) more than any other – political, legislative, administrative or financial – initiative. It may mark a turning point in the perception of digitalization as an indispensable enabler in efforts to bridge and maximize health care system capacities and potentials, empower patients and as a tool to mitigate the impact of future pandemics (Stanimirović & Matetić, 2020).

Table4.3 outlines current e-Health applications in Slovenia. These are designed around standards of interoperability.

Table4.3

Two of the most important developments in the Slovenian e-Health architecture are the national CRPD and the zVEM patient portal. The CRPD is the core of Slovenian e-Health infrastructure. It contains over 50 million records, is compliant with personal data protection and data security standards and enables information exchange between providers. Over 100 000 transactions occur on the platform hourly; over 20 000 new documents are stored. Generally, CRPD is used by all public health care providers and the share of concessionaires is growing. At the last estimation, 20–30% of concessionaires are using CRPD. zVEM, rolled out in 2017, serves as a connecting service for all essential e-Health solutions (Table4.3). It became the most important national digital solution during COVID-19, providing patients with crucial health care documents and information throughout the pandemic. Further, ignoring fluctuations due to the pandemic, the number of patients’ visits between January to May 2021 reached 5.3 million (Stanimirović, 2021). Moreover, the share of e-prescriptions monthly reached 93–94%, representing over 1.2 million e-prescriptions monthly on average, while the share of issued e-referrals is over 93% (350 000) on average monthly.

The Prime Minister(PM)’s 22-member Advisory Board for the health system reform process has been meeting weekly to advance reform efforts. (See the policy analysis of 3 February 2023: “Whole-system Health Reform preparation formally launched in Slovenia”.) It has several subgroups, including medical faculties, primary care, financing of healthcare, health system governance, emergency medical services, and absenteeism. By the end of April 2023, it had prepared the following recommendations:

- Medical education – increase future admissions by at least 20%; enhance training capacity in regional hospitals and establish a possible third medical faculty.

- Absenteeism – address the current impasse, in which many patients experience a status between long-term sickness absence and disability.

- Primary care – clarify the status of patients not able to register with a GP of choice; incentivize junior doctors to choose primary care; revise completely the existing capitation formula, which has been applied since 2017 for workforce calculation, despite not being designed for this.

- Pharmacies – strengthen the role of pharmacies in local communities, potentially adding preventative services.

Additionally, three legal acts are under public discussion:

- Separate law for the Health Insurance Institute of Slovenia (HIIS): A separate law on the HIIS would reform the status, set-up and management of HIIS. HIIS would be registered as an insurance company, not a public institution. Rather than three management bodies – the CEO, the Management Board and the 45-member Assembly (25 insured representatives, 20 employers representatives) – the CEO and Board of three members – General CEO, vice-chair for compulsory health insurance and vice-chair for long-term insurance – would merge. The Assembly would also decrease to 11 members, representing the insured (6), employers (2), government (2), and employees of the HIIS (1).

- Law on digitalisation of the health information system: A special independent agency would be set up to oversee and implement the entire e-health and national reporting infrastructure. This would be managed by a special company and financed from a fixed percentage of the total health insurance budget. This is initially set at 3% and increased to 4.5% after three years; altogether, almost 10 times more money would be dedicated to e-health and digitalisation than currently, though there are some doubts to the feasibility of the funding source. Further, all national registries and data collection would transfer to five basic registries. It is unclear how these would be managed content-wise or by what methodology since the new agency would primarily oversee IT infrastructure. Nor is it clear how the complex international reporting obligations to Eurostat (legally binding), WHO and OECD would be fulfilled under this new system.

- Abolishment of complementary health insurance (CoHI) and corresponding amendments to the Health Care and Health Insurance Act (HCHIA): Triggered by a large increase in premiums by one CoHI company of almost 30% from 1 May 2023, the PM announced the future abolishment of CoHI. The proposal includes a freeze on premiums until September 2023 by which time the necessary amendments to the HCHIA should be adopted. This means that the present system of expansive CoHI would cease to exist by January 2024 at the latest. While this change may be an opportunity to (re)define the basic benefits basket and establish co-insurance for services not covered, it is unclear when and how this will occur.

References

- Law on the Health Insurance Institute of Slovenia, Draft law: https://e-uprava.gov.si/si/drzava-in-druzba/e-demokracija/predlogi-predpisov/predlog-predpisa.html?id=15438

- Law on the Health Information System: https://e-uprava.gov.si/si/drzava-in-druzba/e-demokracija/predlogi-predpisov/predlog-predpisa.html?id=15432