-

09 April 2024 | Policy Analysis

Health expenditure in Slovakia set to rise 11.5% in 2024

3.3. Overview of the statutory financing system

3.3.1. Coverage

Breadth: who is covered?

All Slovak residents are entitled to social health insurance, excluding those with valid health insurance in another country, which may be related to their job, business or long-term residence. People seeking asylum and foreigners who are employed, studying or doing business in Slovakia are also covered. Those insured are entitled to services according to conditions set in legislation and have an equal right to have their needs met, regardless of social status or income. Social health insurance is universal, based on solidarity, and guarantees free choice of HIC for the insured. Payment of contributions is a condition for receiving benefits. With the exception of those covered directly by the state (the state-insured), whose contributions are paid from general tax revenue, the insured are obliged to make monthly advance payments and to settle any outstanding balance on their total social health insurance contributions annually. If this obligation is not met, the insured are only entitled to emergency care, maternity services, mandatory vaccinations and basic care for chronic diseases. In practice, only a small share of residents is not covered: mostly those who are officially living and/or working abroad and paying for health insurance there.

Despite strong regulations on the scope of covered services, HICs can attract new members by offering additional services such as discounts or reimbursements on co-payments for some medicines, vitamins or non-health care services; shorter surgery waiting times; broader preventive examinations; or a variety of supporting electronic services.

Scope: what is covered?

The Slovak Constitution guarantees every citizen health care under the social health insurance system according to the conditions laid down by law. The law outlines a list of free preventive care examinations; a list of essential pharmaceuticals without co-payment; a list of diagnoses eligible for free spa treatment; and a list of priority diagnoses (roughly two thirds of ICD-10 diagnoses). All health procedures provided to treat a priority diagnosis are provided free of charge. Non-priority diseases may be subject to co-payments, though in practice nearly all non-priority treatments are provided free of charge.

Every provider is obliged to publish a price list which is visible to visitors and reviewed by SGRs. This price list must contain prices for non-medical services and is meant to improve transparency for patients.

Depth: how much of the benefit cost is covered?

Cost-sharing mainly takes place through a system of small user fees for certain health services (for example emergency care), as well as co-payments for pharmaceuticals and spa treatments. A law passed in 2006 lowered some of the user fees and in some cases abolished them completely. In 2014 a policy abolished the practice of HICs reimbursing co-payments for health services. Providers are not allowed to take payments from patients once they have a contract with the patient’s HIC, with the exception of some premium services (for example, an option to choose a surgeon in a hospital). However, in many cases providers request payments for services on a voluntary basis, indirectly forcing patients to pay for services that are fully covered (see Section 3.4).

In practice, coverage is also defined by an available budget and a “programme decree” (see Section 3.3.4), which is a legislative tool used by MZ SR for defining each HIC’s minimum spending limits for each category of medical services, as well as overall maximal spending, as illustrated in Table3.4.

Table3.4

3.3.2. Collection

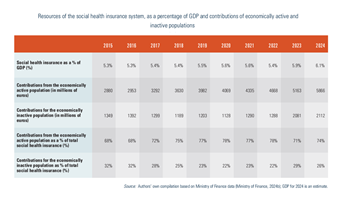

Social health insurance is financed through a combination of contributions from the economically active population and contributions on behalf of the state-insured: (1) contributions from employees and employers; (2) contributions from self-employed persons; (3) contributions from the voluntarily unemployed; (4) state contributions for the state-insured. Contributions are collected and administered by HICs.

From 1 January 2023, the “minimum premium” applies when paying employee contribution (that is, the minimum threshold for the employee’s share of the monthly contribution, irrespective of their wage/salary level). It is calculated as 15% of the amount of the living wage valid in January of that year. For January 2025, it was €41.08 per month; if an employee’s calculated share based on their wage/salary is less than €41.08 per month, they must pay the difference. The minimum premium does not have to be paid by employees who are also insured by the state (for example, working students, pensioners) or persons with disabilities or the self-employed (Samostatne zárobkovo činná osoba). Further details are as follows.

1. Employees pay 15% of their gross monthly income as a mandatory insurance contribution. Out of this percentage, employees pay 4% and employers 11%. If a person has a disability,[4] only half of these premiums (2% and 5.5%) are paid by the employee and employer respectively. The percentage rate of contributions was increased at the beginning of 2024 as part of the public finance consolidation package approved by the government at the end of 2023. The increase was by 1 percentage point (0.5% in the case of disabled employees) and paid as an employer’s contribution to the insurance funds.

2. Self-employed people have the minimum assessment base for 2025 set as 50% of the average monthly income two years ago (€1430), that is, €715. The monthly premium is as follows.

- At least €107.25 for the self-employed without disability. The maximum amount is not determined (the premium, mentioned above, is calculated from the income actually achieved or from the assessment base from business income and at a rate of 15%).

- At least €53.62 for the self-employed with a disability. The maximum amount is not determined (the advance is calculated from the actual income or from the assessment base from business income and at a rate of 7.5%).

- For the self-employed person who is also an employee or insured by the state, the premium may be less than the stated minimum amounts. All contributions are paid directly to HICs, and in the case of multiple jobs there is an annual accounting for those insured.

3. The voluntarily unemployed are obliged to pay the same minimal contribution as self-employed individuals (€107.25 per month in 2025).

4. Contributions for the state-insured are paid on behalf of economically inactive individuals, predominantly children, students up to the age of 26, the unemployed, pensioners, persons taking care of children aged up to 3 years, and disabled persons (see Table3.5). This is around 2.9 million residents in Slovakia. For the period 2004–2019 contributions for the state-insured, which are paid from general taxation by MZ SR, were set by law at 4% of the average wage two years prior to the year in question.

Table3.5

In 2019 the fixed percentage was abolished and instead a calculation based on average wages was introduced – total payment for the state-insured was to be determined as a residual needed to cover expenses. MZ SR and the Ministry of Finance were supposed to calculate the budget for the following year, considering all non-policy changes (such as inflation or ageing), policy changes (such as reforms) and cost-saving initiatives, with the outcome being a final sum of expenditure expected the following year. The contributions for the state-insured were meant to be calculated as the difference between this calculated sum and expected contributions from the economically active population. The Ministry of Finance wanted the system to be more resilient and less dependent on economic activity and political influence in the country: that is should economic activity decline, state contributions should increase to ensure that the health system would have sufficient funds to cover all expenditures.

This mechanism did not work as intended, leading to a decrease in the share of contributions for the state-insured. It turned out to be more prone to political influence compared to the legislative 4% base. The Ministry of Finance refused to provide MZ SR with the required contributions, resulting in losses for HICs and disruptions in contracting. The Ministry of Finance eventually had to increase the contributions for insurees covered by the state (for example in March and November of 2022) but these were not guaranteed, unpredictable and often implemented in a way that only benefited VšZP, further distorting stability. As a consequence, in December 2022 legislation was amended to return to a fixed contribution for the state-insured, defined at 4.5% in 2024 and 5% from 2026 onwards (SITA, 2022a).

- 4. Disability is assessed by the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family. ↰

3.3.3. Pooling of funds

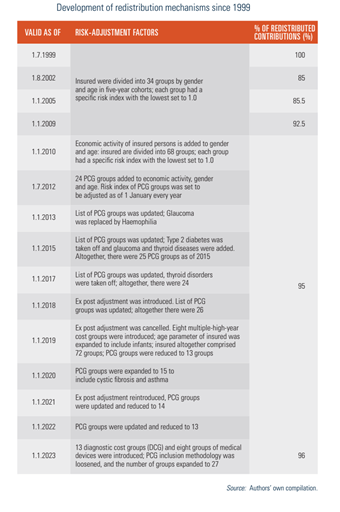

Insurance contributions are collected directly by HICs from employers, the self-employed, the voluntarily unemployed and the state on behalf of economically inactive persons. In order to compensate HICs for more expensive patients (that is, a higher risk portfolio), 96% of social health insurance contributions are redistributed among HICs using a risk-adjusted scheme.

The ultimate beneficiary of the redistribution mechanism is VšZP: from €98 million in 2010 to roughly €449.7 million in 2023. This increase is also seen in the rise of VšZP’s income from redistribution: from 4.1% in 2010 to 6% in 2014 to over 9% of total income in 2023 (Dôvera, 2022a; ÚDZS, 2022).

The risk-adjustment scheme and redistribution process are administrated by ÚDZS. Details of the redistribution procedure are regulated by MZ SR on an annual basis. ÚDZS is also responsible for administering the central register of the insured. Risk-adjustment is performed on a monthly basis and is accounted annually. The scheme has been reformed many times (see Table3.6), out of which two initiatives are of particular importance.

Table3.6

1. Introduction of pharmaceutical cost groups in 2012

Until July 2012 the redistribution scheme between HICs used the categories of age, gender and economic activity of insured individuals in the risk-adjustment formula. Predictive ability of this model was approximately 3% and hence “penalized” HICs that had chronic and expensive patients in their portfolios (HPI, 2014). This was particularly true for VšZP, which was the only insurer in 1994 and still covers a relatively large group of elderly and more complex insured members (often state-insured).

In order to improve the fairness of the redistribution, a new redistribution mechanism was implemented in July 2012. It added 24 pharmaceutical cost groups (PCGs) to the risk-adjustment system, which are based on the consumption of certain amounts of defined daily doses (DDDs) of drugs within the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification over a 12-month period. Taking into consideration that approximately 30% of HICs’ expenditure went to pharmaceuticals; this model significantly improved the predictability and fairness of the redistribution scheme. As a result, VšZP recorded a 7% increase in revenue in the first year of the new mechanism at the expense of the privately owned Union and Dôvera.

2. 2019–2023: “Gupta” adjustments

MZ SR and the Association of Health Insurance Companies Slovakia contracted the Dutch consulting group Gupta in 2018 to undertake an unbiased, in-depth overhaul of the redistribution mechanism. Recommendations of the study were approved by all three HICs and are set to be fully implemented in the coming years.

The first change, implemented in 2019, was an introduction of eight multiple-high-year cost groups that looks into total expenses per insurees over the past three years. This led to an overall increase in the accuracy (also known as R2) of the mechanism, despite rendering several PCGs ineffective. Hence, their number decreased from 26 to 13 since they had no impact on the mechanism. Ex post redistribution of extreme costs was also temporarily taken off to see the impact of changes. The resulting R2 was estimated to be around 27.5%, a significant increase from the previous accuracy rate of 19.9% (GUPTA, 2018).

The second stage of changes was introduced in 2023. MZ SR introduced 13 diagnostic cost groups since several diagnoses cannot be efficiently captured by pharmaceutical expenditure and eight groups of medical devices to cover long-term and social care expenses that were also often overlooked by the existing mechanism. MZ SR also changed a threshold for introduction of PCGs, resulting in the increase of their number to 27. Compared to changes in 2018, the impact on the strength of the mechanisms is expected to be smaller. As of 2023, the risk-adjustment scheme in Slovakia has an estimated predictive ability around 28.7–29% (GUPTA, 2018; ÚDZS, 2022).

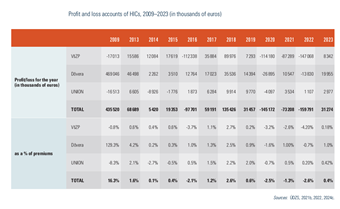

Regulation of HICs’ profits

Since 2004 all three HICs compete in Slovakia as joint-stock companies. Up until 2023, there was no specific regulation focused on profits and dividends of HICs. Across the three HICs, there has been a broad variation in profit and ability to pay dividends to shareholders. As shown in Table3.7, even though HICs have not achieved significant profits in recent years, over the long term the profitability of the privately owned HIC has been significant.

Table3.7

As of 1 January 2023 HICs have a regulated profit ceiling of 1% of the prescribed insurance premium in the gross amount, adjusted for the effect of the redistribution of insurance premiums. If a HIC achieves a positive economic result that is higher than the 1% of the premium, the difference must be used to create or supplement a health quality fund which is used to finance, for example, the payment of special medicines, medical procedures or the implementation of preventive programmes (ÚDZS, 2023b).

On 20 March 2024, the Ministry of Health published Decree No. 55/2024, which defines the amounts of expenditure for each type of health care in the budget for each of the three health insurance companies (HICs) for 2024 (the so-called Programme Decree).

Health insurance expenditures are expected to be 11.5% higher than in 2023, amounting to EUR 7.68 billion in 2024. The primary drivers of the increase in expenditures are hospitals (19.3% annual increase), medical devices (18.5%) and outpatient specialized services (11.4%), as captured in Table 1.

Table 1

The budget, despite the fact that there is a fixed payment for the state’s policyholders from 2024 onwards, is calculated as in previous years, that is, the sum of expenditure for existing policies, for policy changes and subtracting the planned austerity measures, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Impact of existing policy measures’ growth on 2024 expenditure

Without taking any new measures, the expenditure on health services will grow by roughly EUR 521 million. The largest increase is due to wage growth in the sector, followed by medicines and medical devices, inflation and ageing.

Each year, the budget assumes that health workers’ wages will grow at the same rate as the average wage in the economy. The total of these automatic wage increases for all hospital and ambulance staff is set at EUR 253 million for 2024, representing a 7.7% annual increase in the basic component of the wage and the components linked to it.

Due to the categorization of new medicines and medical devices that already took place in 2023, a natural increase is also budgeted for this item, with an expected increase on medicines and medical devices by a total of EUR 124 million.

The budget also covers the natural increase due to inflation and ageing. Expected CPI inflation, which was forecast by the Finance Ministry when the budget was drawn up, is projected at 4.9% for 2024. The natural growth in health care output, and hence in ageing expenditure, is budgeted at EUR 43 million.

Impact of policy changes on 2024 expenditure

EUR 283 million is earmarked in the decree for measures and priorities of the ministry that go beyond natural growth, as explained in the previous section. The largest policy change is the additional financing of institutional health facilities to the amount of EUR 261 million above the growth in personnel costs and inflation, prioritized for the following purposes:

the top-up funding of hospitals under the competence of the Ministry of Health for an amount of EUR 191 million, and

to cover the increase in production due to the reduction of waiting times, the introduction of DRGs and the implementation of the optimization of the hospital network, with a budget of EUR 70 million.

The top-up is aimed at activities that are not sufficiently taken into account and covered under today’s payment mechanism. Without the increase, further indebtedness of hospitals would be imminent for 2024. Slovakia is already facing a lawsuit from the European Commission before the European Court of Justice for late payments by state hospitals. The Commission is calling on Slovakia to address the problem systemically and this increase should be a basic and first of many initiatives to improve financial state of state-owned hospitals.

Depending on the success of the implementation of the austerity measures (see below), additional resources may also be brought into outpatient healthcare. The full savings potential amounts to EUR 100 million; the realized savings will be redirected to the outpatient sector, the final amount of which may be lower and will depend on the success of the implementation of the measures

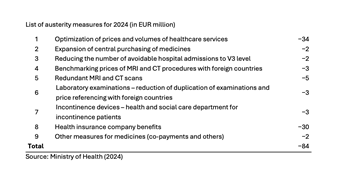

Austerity measures planned for 2024

The potential for austerity measures (stemming from the 2022 spending review) is estimated at EUR 84 million. Successful implementation of austerity measures is a prerequisite for the implementation of the new catalogue of procedures in the outpatient sector. A list of these measures is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Authors

References

3.3.4. Purchasing and purchaser–provider relations

In theory, purchaser–provider relations are based on selective contracting under MZ SR regulation to ensure accessibility and service quality. MZ SR’s regulatory power has expanded in recent years, however, leaving HICs with limited scope and resources. MZ SR defines a minimum of clinical full-time equivalents (FTEs) in ambulatory care that a HIC has to cover in each of the SGRs. In hospital care, MZ SR (in consultation with providers, HICs and the Ministry of Finance) defines a list of hospitals with exact medical programmes that HICs must contract.

MZ SR defines neither the values of these contracts nor exact prices, leaving HICs free to define tariffs; hospitals are currently using a DRG mechanism that has unified predefined values for hospitalized cases and MZ SR is finalizing a price list of treatments for outpatient providers. This pilot list is to be put into practice during 2025, further undermining opportunities of HICs to selectively contract providers.[5] Moreover, since 2021 MZ SR has published a binding decree that defines minimal values (that is, spending levels) that HICs have to contract per each type of care. This is called a “programme decree”.

Apart from these limitations, HICs are theoretically free to contract with other providers. HICs may have different contracts with different providers and negotiate quality, price and volumes individually. HICs publish lists of contracting criteria, which includes technical and personnel requirements, quality indicators, accessibility and other factors, every nine months. In practice, these criteria are primarily used for sectors that are not yet heavily regulated by MZ SR, such as outpatient diagnostic services or day care services, or are focused on shaping the behaviour of providers, for example via pay-for-performance contracts.

Having met the criteria set by a HIC, the contractual parties can settle on conditions, including the scope and price of health services. The minimum duration of a contract is one year, but in practice contracts are negotiated on a regular basis even several times per year. HICs are required to publish rankings of providers, as well as a list of contracted providers as of 1 January every year.

The purchasing power of HICs to set tariffs and prices and their oligopolistic market power has stimulated health professionals to group into networks to strengthen their negotiation position vis-à-vis HICs. Examples include the Zdravita or ZAP association of outpatient physicians, which negotiates on behalf of approximately 5000 outpatient providers.

- 5. At the time of writing the list had not been released. ↰