-

03 April 2023 | Country Update

Proposed updates to the Slovak Recovery and Resilience Plan -

10 December 2021 | Country Update

Continued optimisation efforts of the network of hospitals (OSN)

4.1. Physical resources

Major updates to the Slovak Recovery and Resilience Plan have been proposed nearly two years after approval. There are four types of amendments to distinguish between:

- The largest group of the proposed amendments are administrative, that is, formal amendments that have no real impact on projects. This involves the unification of nomenclatures, corrections of typos, or small textual adjustments.

- The second-largest group was caused by changes beyond the control of the Ministry of Health. For example, the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the consequences this aggressive act has had on driving up prices for materials, labour, and energy. The rise in the prices now means that fewer beds can be built or renovated with the same budget. Hence, while it was possible to support 2400 beds at price from 2020/2021, in 2023 it is possible to subsidize a renovation of only 1602. Thus, the ministry reduced the expected number of subsidised hospital beds.

- The third group of modifications regards the content and conditions of the projects. This impacted, for example, a project to support the creation of new GP practices. While in the original plan, only GPs could receive a subsidy, after the adjustment, the subsidy will be open to other outpatient specialisations.

- The last group of changes significantly changes or cancels entire projects. The most notable of these was altering a project that aimed to restore emergency service vehicles. The ministry acknowledged the project is no longer feasible within the given schedule and was abandoned. Approximately EUR 23 million from this project will be shifted to hospital projects.

Authors

To follow up on the unsuccessful “Stratification” reform from 2019, this reform is focused on defining typologies of hospitals and setting rules for improving the safety and quality of hospital care.

The legislation, passed in December 2021, defines the procedures on how to create the new network of inpatient providers. It outlines that there are to be five types of hospitals and defined the process on how hospitals will be selected. Regarding safety and quality, the reform gives patients the right to be treated and treated within the maximum waiting period determined by experts. Finally, the reform also includes the introduction of a new way of defining the minimum network of providers of general outpatient care.

Slovakia has both one of the densest networks of hospitals in the EU and one of the worst rates of avoidable mortality. Staff shortages are a serious and growing problem as well. The Ministry of Health, with these efforts, hopes to improve regulation and how the health system, along with its physical and human resources, are organized.

Authors

4.1.1. Capital stock and investments

In 2014 there were 10 141 outpatient and 174 inpatient facilities in Slovakia (see Table4.1). Inpatient facilities comprise two groups of providers: 73 general and 44 specialized hospitals. Whereas outpatient facilities are predominantly owned and managed by the private sector, the inpatient sector has mixed ownership, with key university and teaching hospitals being under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Health.

Table4.1

Slovak hospitals suffer from underfunding, which leads to a deterioration in their infrastructure owing to poor maintenance. Several investments made by the Ministry of Health and relevant EU programmes targeted outdated facilities, which continue to require even higher levels of capital renovation (see section 2.8.6). The Slovak health care capital formation was found to be only 59.3% of that of the Czech Republic and just 30.8% of Austrian gross capital volume. Estimates of additional investments needed in order to meet EU15 averages range from €3.9 billion by the Ministry of Health (MoH, 2013a) up to €8.3 billion in the worst case scenario by HPI (Pažitný et al., 2014).

Although the Ministry of Interior built a new hospital in Bratislava in 2016 (costing more than €50 million), the Ministry of Health does not envisage any funding for similar projects in the foreseeable future. The Ministry of Health has since looked to the private sector as an alternative source of needed capital. Since June 2013 the Ministry of Health has been involved in publicprivate partnerships to replace three existing public hospitals in the city; the new university hospital in Bratislava is the first project to be realized through a publicprivate partnership. The realization of the project is expected to be finished by the end of 2016, with estimated initial capital expenses of €250 million.

Almost all outpatient facilities are in private hands. A proportion of outpatient specialists are employed by hospitals and provide ambulatory care in polyclinics attached to hospitals. The number of specialists increased due to a reform in 2005 enabling all specialists to enter the market after fulfilling the obligatory criteria (see Table4.2).

Table4.2

4.1.2. Infrastructure

In 2014 there were 22 959 acute, 4431 psychiatric and 3158 long-term beds in the Slovak health care system. Roughly 46% of these beds were owned by the state, regions or municipalities, 37% by private companies, 8% by mixed entities and 9% by others (Pažitný et al., 2014). Table4.3 shows the ownership and legal status of inpatient facilities.

Table4.3

In the late 1990s Slovakia had one of the highest number of acute beds per 100 000 population in Europe. By 2013 the number of acute beds had decreased by 30% and reached a comparable level to that of Poland, but was still above the EU 28 average (see Fig4.1).

Fig4.1

The gradual decline in beds was conceptualized in the Bed Reduction Plan of 2002 which has since then cut roughly 6000 beds. Additionally, the GHIC decided on another 3000 bed reduction during 2010–2011 by not contracting with selected departments in hospitals. Over the same period the number of long-term beds dropped by roughly 50%, whereas psychiatric beds were only marginally reduced (Table4.4). In the Strategic Framework for Health 2014–2030 acute care beds are to be further reduced to roughly 11 000 beds. This would translate into a further reduction of acute beds by 52% compared to 2014. Simultaneously, occupancy rate should reach 85% by 2030.

Table4.4

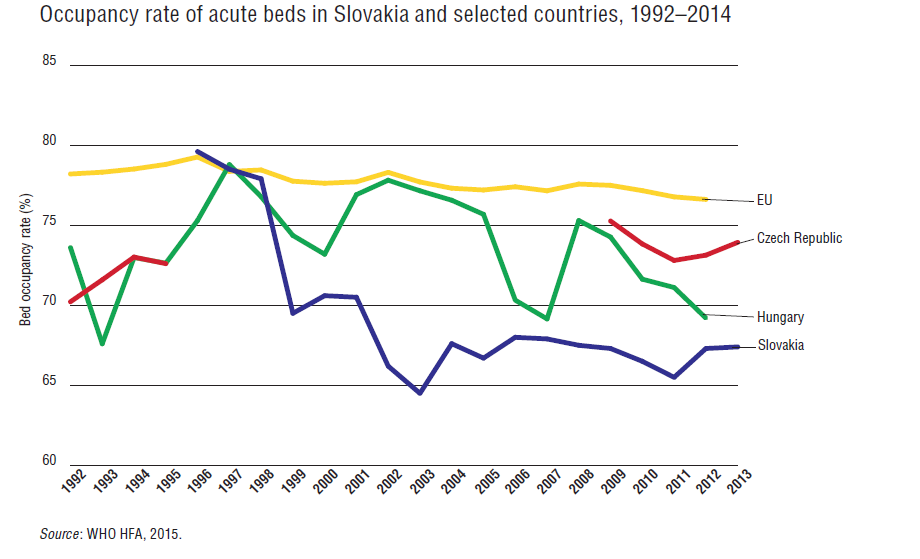

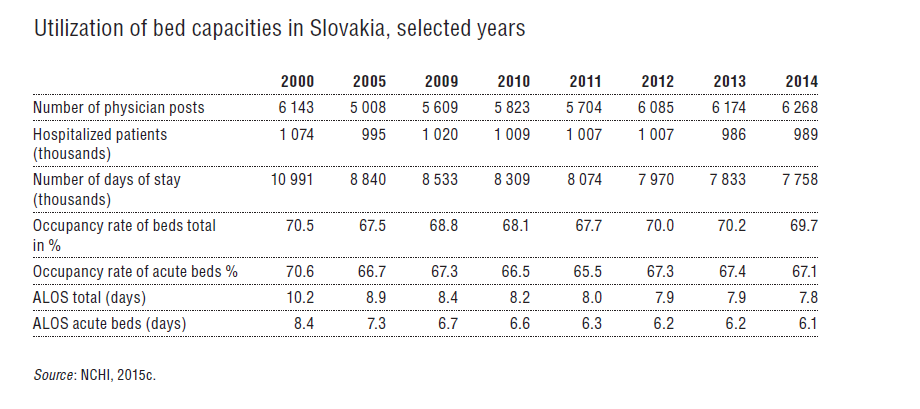

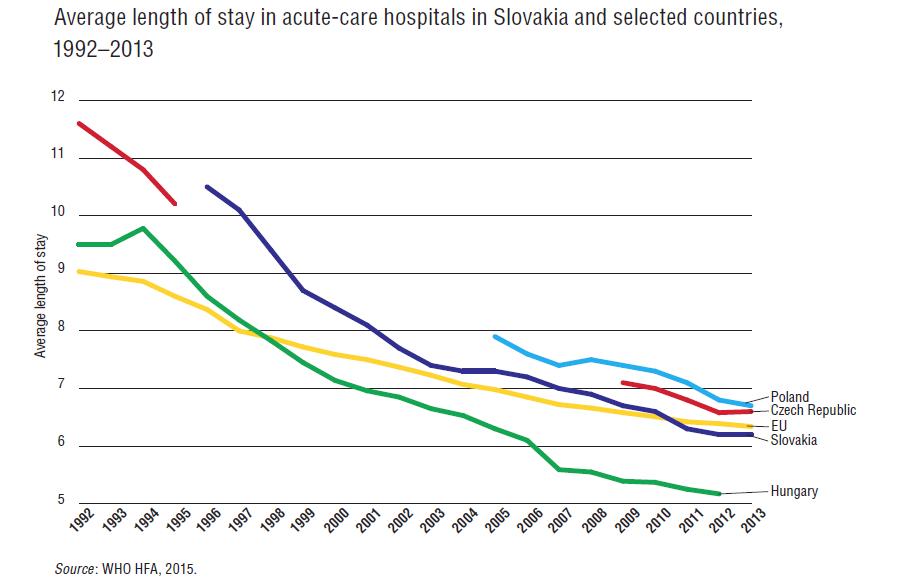

In 2014 occupancy rates of acute beds had declined to 67%, despite only marginal declines in the number of hospitalizations. This is on a par with V4 countries but about 9 percentage points lower than the EU28 average (see Fig4.2 and Table4.5). Reductions in the ALOS (see Fig4.3) facilitated by the growing number of day surgeries (see section 5.4.1) account for these declines. Indeed, ALOS for acute beds was recorded as 10.2 days in 2000 (i.e. roughly two days higher than the EU28 average) and 6.1 days in 2013 (i.e. significantly lower than the EU28 average), reaching lower levels than those in Poland and the Czech Republic or the EU28 average.

| Fig 4.2 | Table 4.5 | Fig 4.3 |

|  |  |

A minimum network of providers regulates capacity in terms of density and accessibility in the Slovak health sector. In primary care, a GP is entitled to a contract as soon as a patient registers with them. In ambulatory secondary care, the minimum network is defined as a minimum number of contracted specialists by type in a given region. In inpatient care, the minimum network is defined in terms of the minimum number of contracted beds per specialty. The HIC may contract more capacity if resources are available. In 2007 the Ministry of Health introduced another regulation – a concept of “compulsory network of providers” – which mandated that certain state-owned hospitals must be contracted, even if quality and price did not match those of their competitors. The idea was that hospitals included in the compulsory network are the ones needed to ensure the provision of acute care services in Slovakia. However, some perceive this regulation as deforming the market, regionally misbalanced and established just to improve the bargaining power of public providers (Szalay et al., 2011). In fact, as of 2016, 36 out of 37 hospitals in the compulsory network are state-owned. This limits available options for HICs in contracting capacities selectively.

Regional variance in the number of beds per 100 000 population, as well as occupancy rates, prove that the minimal or compulsory network does not ensure regional equality in access to inpatient services (see Table4.6).

Table4.6

4.1.3. Medical equipment

The Slovak health care system is relatively well equipped with diagnostic imaging technologies (see Table4.7). It has by far the highest number of RTGs per million inhabitants among V4 members and a relatively high number of CT, MRI and PET scanners and angiographs. Only Poland has more angiographs and CT scanners and the Czech Republic more MRI scanners. The total number of devices has grown rapidly since 2007 due to the prioritization of the availability of medical equipment in the operation programme “Healthcare” (KPMG, 2013).

Table4.7

The purchasing of large medical equipment and technologies is not regulated by legislation or by a minimum provider network guarantee. HICs decide whether to contract a new diagnostic service by medical providers. HICs use a variety of indicators to evaluate their contracting decision. According to the GHIC, there are only few gaps left in the market (as Box4.1 shows).

Box4.1

4.1.4. Information technology (IT)

In 2014, 82% of Slovakia’s population had access to the Internet, which is comparable to neighbouring countries but slightly less than the EU28 average of 84% (Eurostat, 2015a). A national e-health project launched its initial phase in 2008 and aims at creating e-health capacities and initiatives such as electronic medical books, electronic prescriptions and medication, electronic allocation (i.e. waiting times management), and a national portal of e-health (i.e. all relevant information about service provision and an entry point into services of e-health for patients). However, the implementation has been delayed three times. Already more than 1500 days past the original due date, its current deadline for completion is January 2017. The initiative is mainly financed from EU structural funds with anticipated costs of €47 million. Several analysts expect a fourth delay of the project given a variety of corruption allegations (Beňová, 2015). In 2015 a pilot phase started in four hospitals (see section 2.7.1).

The aforementioned uncertainty over the nationwide introduction of e-health services resulted in HIC-driven initiatives and a wide fragmentation of electronic systems in use. Dôvera developed its own mobile application for an electronic medical card offering online access to medical information, e-prescriptions, costs of treatment and other information. A system called “HospiCOM” allows Dôvera to schedule planned hospitalizations for its insured. Other HICs are also using their own versions of quasi e-health systems.

ICT systems in both inpatient and outpatient settings are diverse and rarely applied to improve value in hospitals via utilizing information on HR processes or logistics. The GESITI study (Šoltés, Gavurová & Balloni, 2014) mapped ICT in 20 hospitals in Košice and Prešov region and concluded that:

- clinical, management and patient information systems varied across mapped hospitals;

- there was a minimal use of systems that aimed at human resources management, ERP systems, logistic and application solutions, process management solutions and customer relationship management systems;

- only 12 facilities regularly used ICT to evaluate customer satisfaction; and

- only seven hospitals had a solid IT security plan.

According to Šoltés, Gavurová & Balloni (2014), this partly contributes to insufficient quality of care in hospitals, poor patient responsiveness, and low value creation in hospitals.