-

13 May 2025 | Country Update

Solutions to cover human resource deficit -

24 April 2023 | Country Update

Approval of sectorial action plans for the development of human resources for health (2023–2030) -

09 August 2018 | Policy Analysis

Measures to alleviate the shortage of human resources in the Romanian health system -

13 December 2017 | Country Update

More specialization opportunities for nurses -

21 May 2017 | Country Update

Measures to bring back Romanian doctors from abroad

4.2. Human resources

The number of practising physicians increased in Romania from 264.36 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2013 to 364.79 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2022. The number of nurses also increased from 51.39 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2013 to 93.54 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2022. This may be explained by reduced emigration following significant salary increases in 2017 and mass hiring during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the increase, workforce shortages persist, particularly among physicians in certain specialties and in some geographical regions.

With the financial support of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan and WHO technical assistance, under the framework of the Multi-annual Strategy for Human Resources Development in Health 2022–2030, the Ministry of Health issued the “Local Action Guide: Solutions for Human Resources in Health”. The document offers specific tools for human resources recruitment and retention and presents relevant case studies and examples of best practices implemented in Romania. The document is based on the WHO Guideline on Health Workforce Development, Attraction, Recruitment and Retention in Rural and Remote Areas, and includes recommendations on targeted educational and professional development policies, financial and non-financial incentives, regulation suggestions, examples of infrastructure improvements and community integration. The guide also lays out the necessary conditions for successful implementation, such as: intersectoral collaboration, training on human resource management and communication.

References

In March 2023, the Minister of Health approved sectorial action plans for human resources (HR) for health development over 2023–2030. These plans follow the approval of the Multiannual Strategy for the Human Resources for Health Development over 2022–2030 in June 2022, which aims to attract health professionals to underserved areas, improve education, recruitment, retention, and motivation of the workforce. They were developed with the assistance of the WHO and take into account reforms set out under Romania’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

The plans include a set of horizontal objectives for the whole health sector, such as improving HR data collection and analysis for better planning, monitoring and evaluation of the workforce, improving HR governance, improving HR education, improving HR management, and specific objectives for each type of health services (primary and community health care, public health, inpatient care, ambulatory specialized care).

Although the plans are very detailed, with assigned responsibilities, deadlines, and monitoring and evaluation indicators for each action, they do not include a dedicated budget for their implementation.More information (in Romanian)

https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/256965

https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/265600

Context

One of the main problems faced by the Romanian health system is the shortage of human resources. Low salaries for health professionals have been identified as the main cause of this problem, especially in public hospitals. This has accelerated the migration of physicians and nurses to other EU countries, and has determined a reduced level of new entries into the system, as the medical profession is no longer attractive for young people. Due to the limited number of health professionals, some hospitals cannot provide even basic services, which implies a decrease in the level of access to health care for the population. The shortage of human resources has also had a serious impact on the quality of the provision of health services, sometimes causing tragedies (for example, the fire burst in the intensive care unit of a maternity facility in Bucharest in 2010, in the absence of the only nurse, who was missing from the room, which claimed the lives of six newborns and injured another five) (Government of Romania, 2017a).

Impetus for the reform

The health professionals, through their trade unions, have put very high pressure on the government to increase incomes in the health sector by organizing protest rallies, strikes and participating in negotiation meetings with government representatives (Dumitrescu, 2017). Health professionals also have gained public support in favour of a change in the existing legislation.

Thus, in December 2017, the government issued an Emergency Ordinance to amend Law 153/2017 on the salary of staff paid from public funds (Government of Romania, 2017b). Law 153/2017 stated a gradually increase in the salary of the staff paid from public funds until 2022. The increase of staff salary in the clinical settings was in line with the Government Programme 2017-2022, where “a motivating salary package for the health professionals in order to stop the physicians’ exodus” was included as part of the government vision (Government of Romania, 2017a).

Content of the reform

The main objective of the new policy that increases health professionals’ incomes is to reduce the shortage of health personnel by decreasing the migration of health workers abroad and even encouraging health workers established out of Romania to return. To achieve the latest, that is to halt external migration and encourage Romanian health workers to return to the country, Law 153 from July 2017 on the salary of staff paid from public funds was modified in December/2017. The original Law stated a gradual increase of salary for all public employees by 2022, but the Law was amended in December 2017, raising the salary of physicians, nurses and other health workers at the level established for 2022, starting 1st of March 2018 (Government of Romania, 2017b).

Following the amended Law 153/2017, government data shows that the net salary of a young doctor has increased by 162% (from about 344 to 902 euros), and the net salary of a senior physician has increased by 131% (from 913 to 2112 euros) (Government of Romania, 2018).

Evaluation

It is still too early to have any assessment that might bring evidence on the effectiveness of the current policy. In any case, the Minister of Health has made public declarations concerning the interest of more and more Romanian physicians settled abroad to return home. Further, the Minister of Health recognizes that increasing salaries alone is not sufficient to tackle the shortage of health personnel, and hence, measures are currently being implemented, with the financial support from the EU structural funds, to also improve their working conditions (for example, equipment, access to consumables, drugs and modern diagnostic tests) (Agerpres, 2018).

References

Agerpres (2018). Salarile mari nu rezolvă exodul medicilor – invitată Sorina Pintea [The high salaries do not solve the physicians’ exodus] Agerpres. Monitorizare Presa (http://files.agerpres.ro/eview.php?i=2E8E79F2E661E97630823178B700447537109004&c=194, accessed 27 July 2018)

Dumitrescu Paul (2017). Federația Sanitas continuă greva [The Sanitas Federation continues the strike] Cotidianul.ro 18 October 2017 (https://www.cotidianul.ro/federatia-sanitas-continua-protestele/, accessed 27 July 2018)

Government of Romania (2017a). Program de guvernare 2017-2020 aprobat prin Hotărârea nr.53 din 29 iunie 2017 a Parlamentului României pentru acordarea încrederii Guvernului, publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, Nr. 496/29.VI.2017 [Programme for Government 2017-2020 approved by the Parliament Decision no. 53/2017 for granting confidence to the Government, published in the Official Gazette of Romania Part I, No. 496/29.VI.2017]

Government of Romania (2017b). Ordonanță de Urgență Nr. 91/2017 din 6 decembrie 2017 pentru modificarea și completarea Legii-cadru nr. 153/2017 privind salarizarea personalului plătit din fonduri publice [Emergency Ordinance No. 91/2017 from 6 December 2017 for amending and completing the Law-framework No. 153/2017 regarding the salary of staff paid from public funds] Monitorul Oficial NR. 978 din 8 decembrie 2017 [Official Gazette no. 978 from 8 December 2017]

Government of Romania (2018). Government of Romania / News / Prime Minister Viorica Dancila presented the Government’s six-month stock-taking report (http://gov.ro/fisiere/stiri_fisiere/Bilant_guvernare__6_luni.pdf, accessed 27 July 2018)

The Ministry of Health in Romania has extended the specialization options for nurses through Order no. 942/2017. New disciplines include: pediatrics, palliative care, psychiatry, dentistry, community care, neonatology, intensive care, pulmonology, clinical pathology, operating room, geriatrics, diabetes, oncology, nephrology, cardiology, gastroenterology, pharmacy.

Until now, nurses in Romania could specialize in fewer disciplines (laboratory, public health and hygiene, balneo-physiotherapy, radiology and nutrition) during an academic year, after the completion of high school or four years in university colleges.

The extension of the specialization programme has the purpose of increasing quality of care and facilitating the relocation of jobs, in case of need.

More information (in Romanian):

https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/ge3dsojtgiza/ordinul-nr-942-2017-pentru-aprobarea-normelor-de-organizare-si-desfasurare-a-programelor-de-specializare-in-vederea-reconversiei-profesionale-precum-si-in-vederea-dezvoltarii-abilitatilor-profesionale

One of the measures in the health policy agenda of the current government to ensure proper human resources for health is the establishment of a National Centre for Human Resources. The main roles of the Centre will be: the assessment of human resources needs, the coordination of training and the guidance in career development.

The legislation describing the organization and functioning and the tasks and responsibilities of the Centre have not been published yet. However, the Minister of Health has made a public announcement regarding the establishment of the Centre within the Ministry of Health and stressed its role in granting assistance to all Romanian doctors abroad who want to return to Romania. According to the Minister’s statement, there are already evidence that Romanian doctors working abroad may wish to return if some terms are changed, including the remuneration level.

More information (in Romanian):

http://gov.ro/fisiere/pagini_fisiere/Programul_de_guvernare_2017-2020.pdf

https://www.agerpres.ro/sanatate/2017/04/01/bodog-de-luni-va-functiona-centrul-national-de-resurse-umane-pentru-medicii-care-vor-sa-revina-in-tara-12-28-14

Authors

4.2.1. Health workforce trends

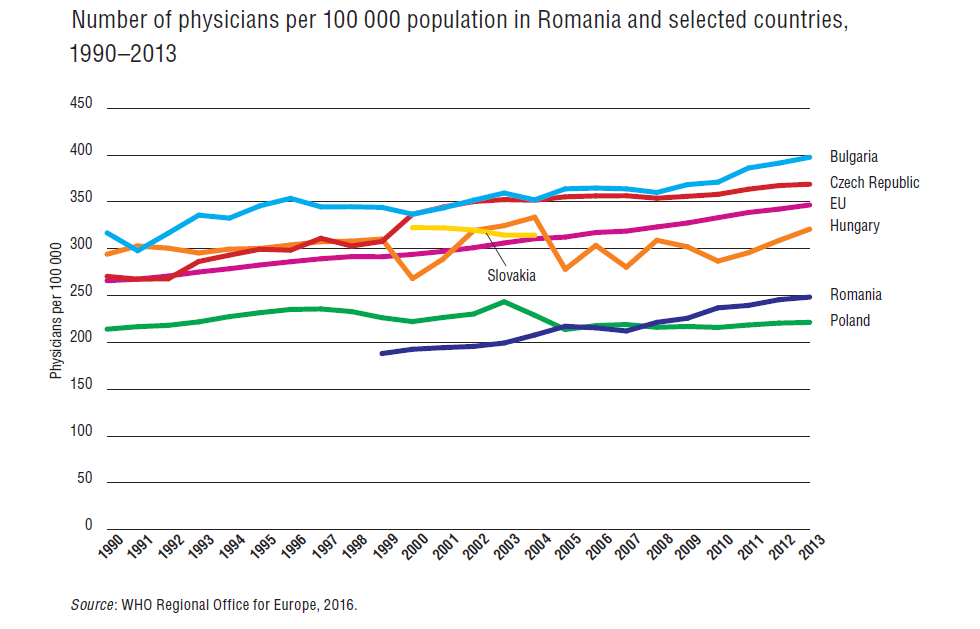

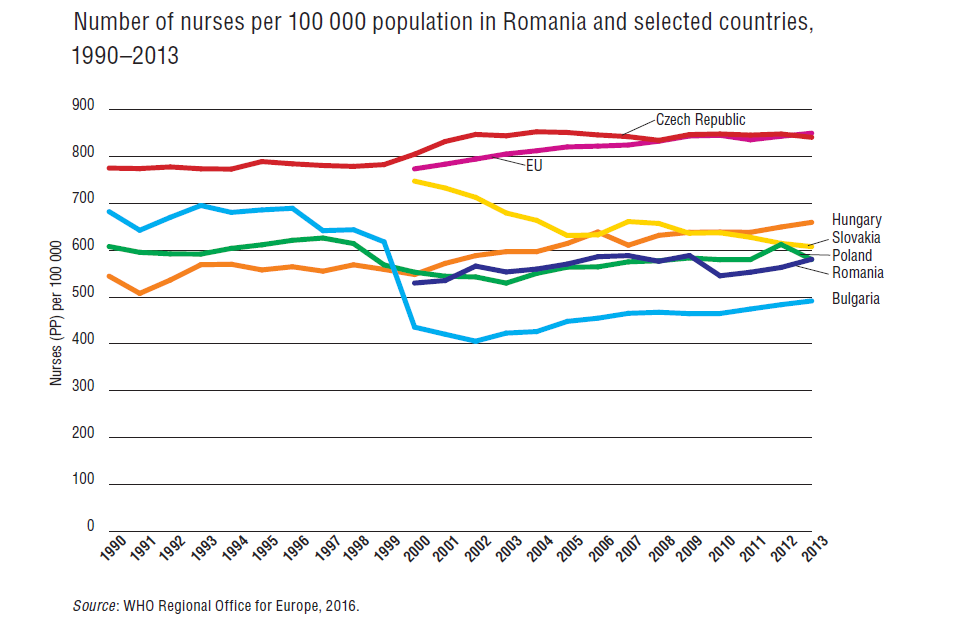

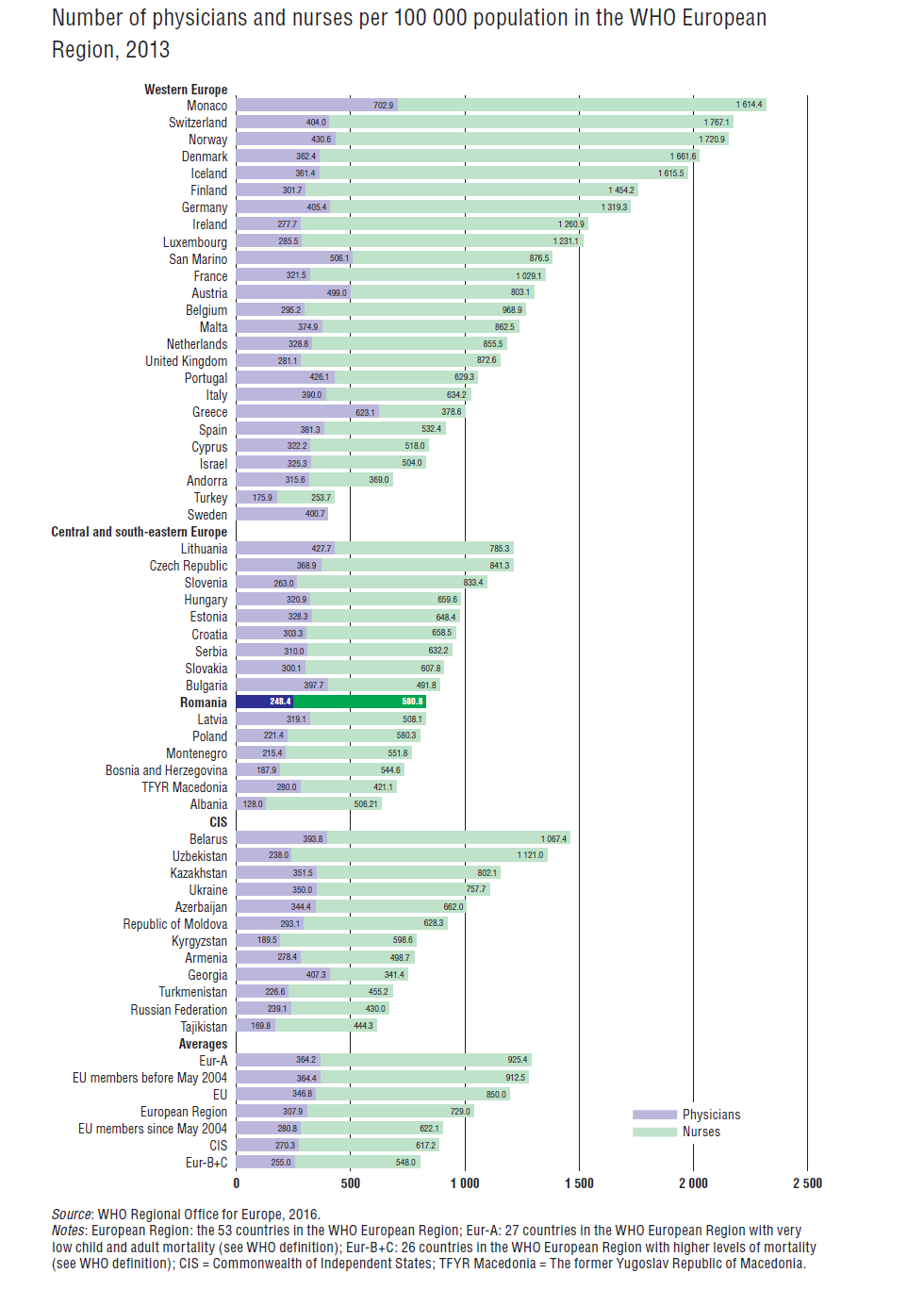

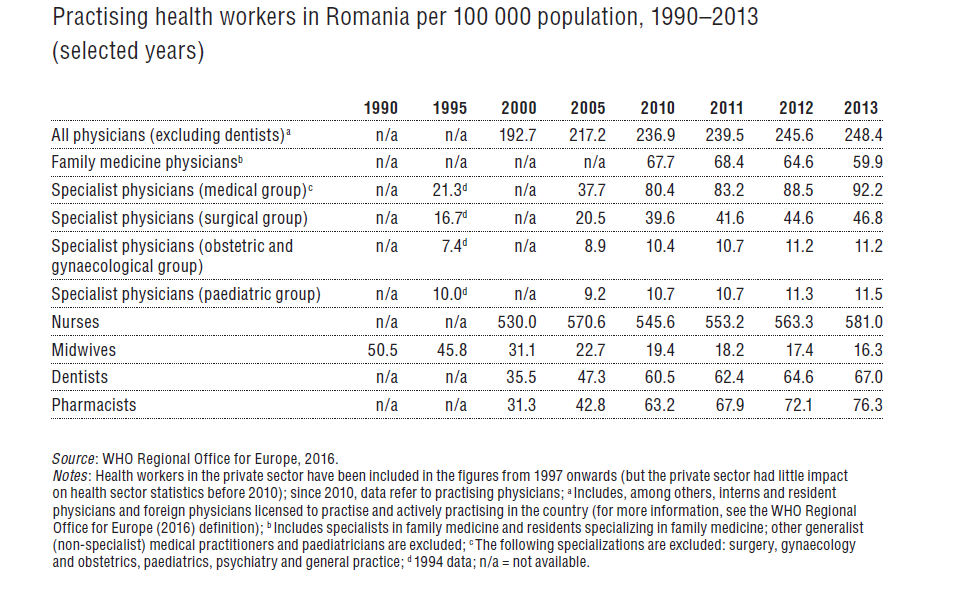

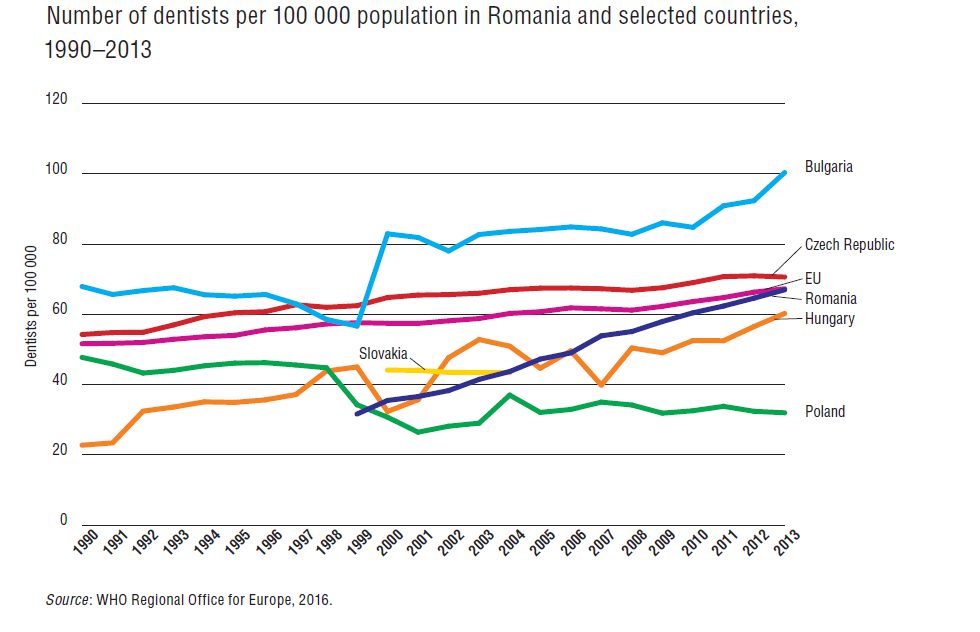

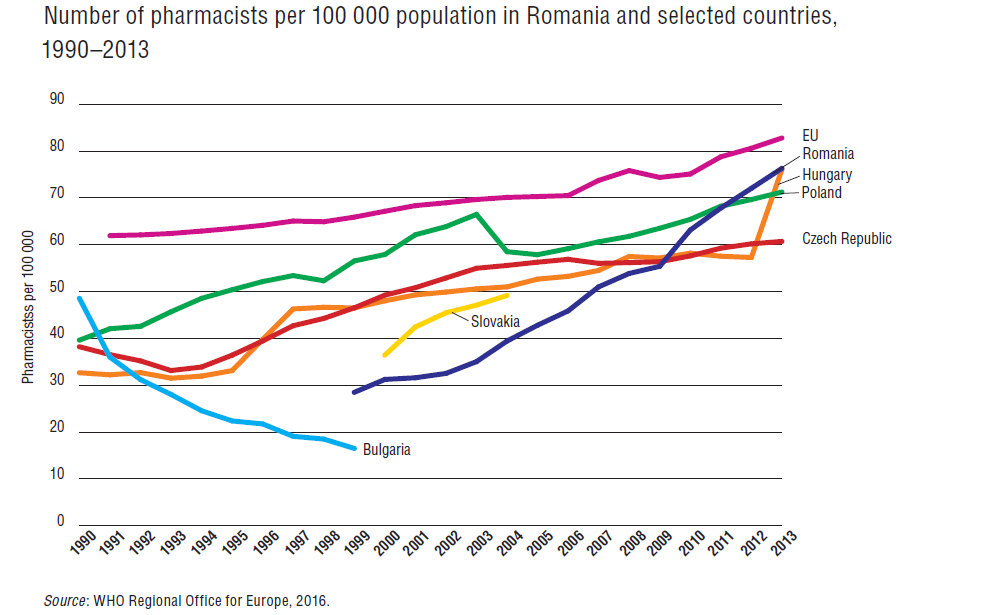

Romania has relatively low numbers of physicians and nurses, at 248 physicians and 581 nurses per 100 000 population in 2013, compared to most comparator countries and the EU average (Fig4.4 and Fig4.5), and compared to other countries in central and south-eastern Europe (Fig4.6). This was despite a steady increase since 2000, of about 20% among physicians and just under 10% among nurses (Table4.2). The number of pharmacists and dentists almost doubled during the same period (Table4.2) and, in 2013, the number of dentists per 100 000 population was, at 67, almost the same as in the EU (67.3) (Fig4.7). The number of pharmacists remained lower, at 76.3 per 100 000 population in 2013, compared to an EU average of 82.8, although similar to Hungary (76.1) (Fig4.8). There is no information on the number of managerial staff working in the health care system.

| Fig4.4 | Fig4.5 | Fig4.6 | Table4.2 | Fig4.7 | Fig4.8 |

|  |  |  |  |  |

Since 1997, all doctors have been required to undertake specialist training (see section 4.2.3) and, in 2013, 23.5% of physicians working in the Romanian health system were family medicine physicians (Table4.2). This is somewhat lower than in 2010, when family medicine physicians accounted for 29% of all practising physicians. It is difficult to be certain about how many doctors work in the ambulatory care sector compared to the hospital sector, or work in the public sector compared to the private sector. This is because doctors working in hospitals can also practise in ambulatory care settings and those working in the public sector may practise in the private sector after hours. In 2013, 49.8% of practising doctors were hospital based (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2016).

4.2.2. Professional mobility of health workers

Over the last decade, Romania has seen a comparatively high number of the health workforce migrating abroad, although there is a lack of precise data on the number and type of health workers moving abroad. According to official statistics from receiving countries, the number of Romanian medical doctors in pre-2004 EU Member States increased from 977 in 2003 to 2433 in 2007 (the year of Romania’s EU accession) (Buchan et al., 2014). Unfortunately, there are no accurate statistics. The majority of Romanian doctors who have migrated work in Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, and countries such as France and Belgium report Romanians to be the most numerous group among health professionals from the Member States that have joined the EU since 2004 (Buchan et al., 2014). The number of Romanian nurses in pre-2004 EU countries rose from 811 in 2003 to 8481 in 2007, with the majority located in Italy (7670 nurses) (Buchan et al., 2014). Romania’s EU accession in 2007 amplified and accelerated the trend of outward migration of doctors and nurses.

The most common reasons for leaving the country include low salaries compared to non-health professions in Romania, low levels of satisfaction with social status and lack of recognition, limited career development opportunities, and discrepancies between the level of competences required and the working conditions (equipment, access to consumables, drugs and modern diagnostic tests) (Wismar et al., 2011). As a consequence of this emigration of health care workers, there is a shortage of some medical specialties and skills at the hospital level in Romania, especially in deprived regions. Even large hospitals experience difficulties in filling vacant positions and these often remain unfilled due to their low attractiveness compared to similar jobs abroad as well as the lack of effective retention policies. Some measures that have been implemented since 2010 to halt the exodus of health workers, such an increase in wages for young doctors, have not been effective. The problem of filling vacant posts was further exacerbated by the government-imposed freeze on all new public sector recruitment introduced in 2010 in the wake of the economic crisis.

4.2.3. Training of health workers

Medical education in Romania takes six years (five years for dentists). The yearly number of medical school graduates in Romania has been stable since 2010, at around 3700 (Olsavszky et al., 2010). After graduation, physicians have to pass an exam in order to enter specialty training. The duration of specialty training is five years for most specialties but may be longer (e.g. six years for neurosurgery), while specialty training in family medicine takes three years, and public health and health management four years. From 2009, undergraduates pursuing a specialist qualification in oral and maxillofacial surgery have to obtain two licences to practise, one in medicine and one in dentistry. The length of the specialization for dentistry is five years. Historically, it was not mandatory for medical graduates who wished to practise as family medicine physicians to undertake further specialist training. However, with the introduction of family medicine as a specialty in 1997, all new graduates who wish to practise family medicine have to undertake specialist training. In 2010, there were 52 medical recognized specialties in Romania (two for dentists) (Olsavszky et al., 2010).

Nursing training takes three years in nursing schools (vocational schools) after completion of high school or four years in university colleges. Nurses can specialize in several disciplines: laboratory, public health and hygiene, balneo-physiotherapy, radiology and nutrition. Specialization takes one year.

Continuing professional development is required for both medical doctors (including dentists) and nurses. The professional associations set the educational standards and the criteria for periodical accreditation of their respective professions. Continuing professional development is validated every five years through the accumulation of a sufficient number of continuous education points. If the minimum number of points has not been achieved, the doctor or nurse must pass revalidation exams.

4.2.4. Doctors’ career paths

The criteria for employment and professional promotion in terms of obtaining a higher professional title (e.g. senior doctor) for physicians working in the public sector are set at the national level by the Ministry of Health, which also organizes exams for the professional promotion of medical doctors. For each specialty, there are several areas in which a physician can obtain a competence (called Atestat), which relate to medical or nonmedical skills in a particular area (e.g. palliative care or management), the use of particular technologies (e.g. bronchial endoscopy) or the ability to perform particular interventions (e.g. gynaecological laparoscopic surgery). To obtain a competence, the physician must undergo training and pass an exam. To become the head of department or a ward, a physician must obtain the competence in health care services management and pass a selection process. In order to become a hospital manager, a doctor or other professional (e.g. a person with nonmedical education) must complete a course in health care management. There is little movement of doctors across public hospitals as hospitals have little influence on the establishment of new departments or changing the number of physicians, which both require approval by the Ministry of Health.

Health professionals working in public health administration at central (Ministry of Health, NHIH) or local levels (DPHAs, DHIHs) have the status of civil servants. This means they are not permitted to receive an income from other forms of employment (e.g. from practising medicine), with the exception of teaching and research. Those trained in medicine who have not practised for five years lose recognition of their professional competence by the College of Physicians.

4.2.5. Other health care workers’ career paths

The criteria for employment and the career advance of nurses are also set by the Ministry of Health, which, in collaboration with the Order of Nurses and Midwives, organizes exams for the professional promotion of nurses. For a nurse, the prerequisite for becoming a head of department or of a ward, or the care director of a hospital, is the completion of a course in hospital management.