-

17 May 2023 | Country Update

Transformation of chronic inpatient care being tested through a pilot program -

02 March 2017 | Country Update

Proposal for the centralization of the financing departments of public hospitals -

27 September 2016 | Country Update

“Chancellor system” in hospital care? -

19 October 2013 | Country Update

Debts of public hospitals increasing -

30 June 2012 | Country Update

Major structural reorganization in the inpatient care sector

5.4. Specialized ambulatory care / inpatient care

The provision of secondary and tertiary care is shared among municipalities, counties, central government and, to a minor extent, private providers. The various providers perform a wide range of activities depending on the level of care (secondary or tertiary), the number of specialties covered (single or multiple specialties) and the type of care (chronic or acute, inpatient or outpatient).

In general, counties are responsible for providing secondary and tertiary care to the local population. In practice, however, municipalities also provide specialist care on the basis of the principle of subsidiarity. County governments usually own large multi-specialty county hospitals, which provide secondary and tertiary inpatient and outpatient care to people with acute and chronic illnesses, whereas municipalities own polyclinics(multi-specialty institutions providing exclusively outpatient specialist care), dispensaries (single-specialty institutions providing only outpatient care, typically to the chronically ill) and multi-specialty municipal hospitals (providing secondary inpatient and outpatient services for acute and chronic illnesses). Outpatient care at the municipal level is provided in hospitals or in a separate building of a previously independent polyclinic later integrated into the hospital.

The central government also owns hospitals, which provide acute and chronic inpatient and outpatient care. These are divided among the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry for National Economy, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Public Administration and Justice, and the Ministry of National Resources. Being part of universities, university hospitals fall within the remit of the State Secretariat for Education, which is part of the Ministry of National Resources. The single-specialty clinical departments of the medical faculties provide both secondary and tertiary care. The State Secretariat for Healthcare, which is also part of the Ministry of National Resources (see section 2.3.3), has single-specialty providers known as the National Institutes of Health, which deliver highly specialized tertiary care only, and a few state hospitals, which are mainly sanatoria that provide medical rehabilitation.

The territorial supply obligation applies to all public providers, but the size of their catchment area depends on the type of care provided and on the estimated number of people in need. The same health care institution can have different catchment areas for different types of care. In general, secondary outpatient care services have been assigned the smallest catchment area, but these are still larger than primary care districts. Tertiary care is offered at least on a regional basis, which includes the population of more than one county. Highly specialized tertiary care services, which are provided to patients with rare diseases, have the largest catchment area, namely the whole country (see also section 2.8.2) (1990/3, 1997/20).

A small private sector is also involved in the provision of specialist care, but providers usually have no contract with the NHIFA and users must therefore pay out-of-pocket. So far, there have been two main exceptions: specialist services with a shortage of public capacities, such as kidney dialysis or MRI, and hospitals owned by churches or charities; these private non-profit providers are integrated into the main system of financing and service delivery (NHIFA, 2010). As part of the government’s plan to rationalize the service delivery structure, the NHIFA has contracted with private profit-making providers for the provision of same-day surgery as well (see also section 5.4.1).

As part of Hungary’s larger health system restructuring (see the update from 7 December 2022), some

In May 2023, a draft legislation was published that outlines the implementation of this change in six institutions, commencing on 1 July. The draft legislation has undergone a social consultation process that concluded on 20 May.

Authors

As a response to the recurring accumulation of hospital debts, the State Secretary for Health would like to bring the employees of the financing departments of hospitals under the National Healthcare Service Center (ÁEEK). The proposal is motivated by the success of the chancellor system of higher education institutions. This reform prevented- at least for a while-the accumulation of debts at universities, including universities with medical faculties, which are among the biggest health service providers in Hungary (both in terms of the number of beds and scale of activity). The proposal has been fiercely opposed by the Hungarian Hospital Association and the Hungarian Medical Chamber, which have successfully blocked the proposal so far.

Authors

The State Secretariat for Health plans to reorganize the

financial management of public hospitals in line with the chancellor

system in place at Hungarian higher education institutions, which was

implemented in the second half of 2014. Each of the 8 health care

regions will be brought under the management of a so-called chancellor,

who will be responsible for the financial management of the health care

providers (hospitals) of the region. One health care region will include

approximately 8-10 hospitals (depending on its structure) and will be

responsible for the care of 1-1.5 million inhabitants.

The State

Secretariat for Health expects that this will eliminate the problem of

regenerating hospital debts, and will increase efficiency by better

coordination between hospitals.

Nevertheless, the Hungarian Hospital

Association does not endorse the proposal on the grounds that financial

and professional decision-making should not be separated and should be

placed as close as possible to the patients, in order to guarantee

better patient safety.

Authors

On 12 June 2013, the media reported that 35 of the main suppliers to public hospitals were unwilling to further tolerate the substantial unpaid debt those had incurred, which reportedly reached 50 billion HUF (≈3% of public expenditure on health) in the first quarter of 2013. On 24 September, it was reported that public hospital debt had reached 98.4 billion HUF (≈6-7% of public expenditure on health). General government expenditure on health itself is still very low in Hungary amounting to 4.9% of the GDP in 2012, a figure which is among the lowest in the last 20 years.

Authors

As part of the reorganisation of hospital services, 2500 active beds (out of 44 000) were eliminated from the system while at thte same time a revised system of referrals was introduced. As of 1 July, 2012 departments in almost 50 hospitals were closed and the provision of acute inpatient care will cease at 15 providers to be replaced with chronic care, one-day surgery and outpatient care. There is a pilot phase of at least one month for the new referral system, during which it is possible to refer patients to healthcare providers according to both the old and the new regions.

Authors

5.4.1. Outpatient specialist services

According to the aforementioned provider typology, outpatient specialist services are provided by polyclinics, dispensaries, municipal hospitals, county hospitals, clinical departments of universities, National Institutes and health care institutions of other ministries (for example, the Military Hospital – State Health Centre under the Ministry of Defence).

Initially, polyclinics employed specialists who worked exclusively in outpatient care. In the early reform phase in the 1990s, the objective was to integrate polyclinics partly into hospitals and partly into primary care. Instead of the three-pronged organization of the Semashko-style health care system during the communist era, integration would have made a two-pronged system of primary care and specialist care. The integration policy did not work, however, leaving several polyclinics that are still organizationally independent.

Dispensaries were established during the communist regime. They provide outpatient care to chronically ill patients with pulmonary, dermatological and sexually transmitted diseases, people with alcohol and drug addiction, and patients with psychiatric disorders. In addition to this chronic outpatient specialist care, dispensaries implement screening programmes in their respective specialties and, additionally, for hypertension, diabetes, cancer and kidney diseases. In 2008 there were 170 dispensaries in Hungary for pulmonary disease, 125 for dermatological and venereal diseases, 135 for psychiatric disorders and 66 for addiction treatment (HCSO, 2010f).

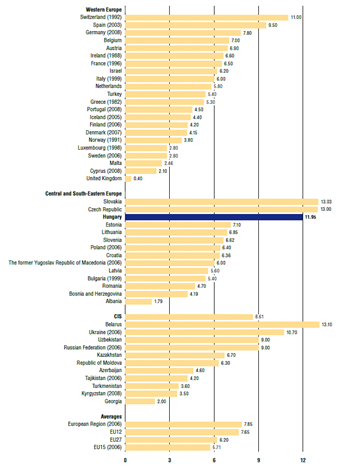

As can be seen in Fig5.1, each person in Hungary had an average of 11.95 outpatient contacts in 2009, which was third among the countries of central and south-eastern Europe after Slovakia (13.03) and the Czech Republic (13.00), and almost twice the EU27 average. High utilization rates in the outpatient specialist sector would not be undesirable if unnecessary hospitalization was avoided as a result. However, acute hospital admission rates in Hungary are also high (17.94 per 100 inhabitants compared to 15.66 for the EU27 average in 2008), albeit following a decreasing trend after the output of hospitals and outpatient specialist providers was limited by the government in 2006 (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2011) (2006/5).

Fig5.1

5.4.2. Inpatient services

In 2009 Hungary had 153 hospitals with an inpatient care contract with the NHIFA and a total of 71 800 approved hospital beds (NHIFA, 2010). Generally, these hospitals provide inpatient care at the municipal, county, regional or national levels, according to their level of specialization, which usually coincides with the hospital’s catchment area. Hospitals that provide care in more than one medical specialty, however, can have different specialization levels for different specialties and consequently different catchment areas. Moreover, a hospital can have different catchment areas for the same specialty, as do clinical departments of university medical faculties, which have a local catchment area for secondary care and a national catchment area for tertiary care within the same specialty.

The principle of the Hungarian health care delivery system is that patients must receive care at the lowest level of specialization that can provide adequate treatment, and may be transferred to hospitals with higher levels of specialization only if necessary (1997/9). Where a patient ends up in the hospital system depends on the frequency of the disease, the severity or complexity of the case, and the cost and complexity of the treatment.

Municipal hospitals usually offer main specialties, such as internal medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology and surgery. According to the minimum legal requirements, a hospital at the first level of specialization is obliged to cover internal medicine, surgery and one other specialty, together with the basic diagnostic facilities (ultrasound, X-ray, ECG, laboratory) (2003/15). Municipal hospitals have the lowest level of specialization and the smallest catchment areas. County hospitals usually cover the whole spectrum of secondary care, providing additional specialties, such as haematology, immunology, cardiology and psychiatry for the population of an entire county. For the basic specialties, county hospitals usually have a local catchment area with the lowest level of specialization and another catchment area covering the whole county, within which they accept more severe or complex cases from municipal hospitals. County hospitals may also provide tertiary care, such as open-heart surgery, for the population of a region comprising more than one county. Finally, clinical departments of university medical faculties and National Institutes provide care of the highest level of specialization for the whole country, but university clinical departments have local catchment areas as well.

The owners of health care providers are required by law to supervise the management of their institutions (1997/20). There are no detailed regulations governing the way that hospital management operates. Hospitals that provide care under the territorial supply obligation are required to set up a hospital supervisory council, whose members can be delegated by NGOs, providers and local governments. This council does not have management rights but can formulate opinions and proposals supporting the operation of the providers; it also represents the interests of the resident population.

In 2003 the Ministry of Health, Social and Family Affairs[19] regulated some aspects of the management structures in public hospitals (2003/11). According to this regulation, the management of public hospitals must consist of a director and deputy directors in a typical pyramid-shaped hierarchical structure. The deputy directors are responsible for areas such as medical, nursing and business operations. In addition, there is a professional management board, whose members consist of medical and nursing directors, as well as the heads of every professional department. This board must meet for at least two sessions per year and can formulate recommendations to the director of the hospital. The consent of this board is necessary for some management issues, including the strategic professional plan of the institution and its quality management policy.

- 19. As of 2010 called the State Secretariat for Healthcare within the Ministry of National Resources. ↰

5.4.3. Day care

Day care in Hungary is defined using a 24-hour limit after hospital admission, which means that patients who are admitted late in the day and spend the night in hospital can also be considered day-care cases. At the same time, minor surgical procedures that do not need any postoperative supervision and emergency cases are not classified as day care (NHIFA, 2003). A special type of intermediate care known as daytime hospital treatment (for example, mental health treatment and rehabilitation services that do not require an overnight stay) is also not considered day care (see section 5.7).

The organizational, infrastructural and human resource requirements of day care are regulated by a ministerial decree (2002/20), whereas further regulations to be observed by service providers are defined in a rule-book published by the NHIFA (NHIFA, 2003). The State Secretariat for Healthcare also has a protocol on outpatient surgery, which was developed by the Professional College of Surgery and the Society of Multidisciplinary One-Day Surgery. Although the ministerial decree has opened up the provision of day-care services to polyclinics, the requirements are stricter than those for inpatient care. For example, physicians must have at least five years of experience providing inpatient care and have performed a larger number of operations, and patients within a polyclinic’s catchment area must be able to access its services within 30 minutes by car.

In the first phase of payment reforms in the mid-1990s, parallel to the introduction of the Hungarian adaptation of the DRG system, 13 diseases and 13 interventions were defined that could be treated/performed in the outpatient setting by inpatient care providers (1994/1). Since then, several modifications have been made in terms of the clinical, organizational, regulatory and payment frameworks of day care so as to improve its implementation, which has been recognized as too slow by policy-makers. In particular, measures were taken to shift more and more potential day cases from the hospital into the ambulatory care setting. Between 1994 and 2010, the scope of eligible interventions has been modified (in most cases expanded) many times, most recently in May 2010 (2010/3).

In late 2010, a total of 340 interventions (mainly surgical procedures, but also some diagnostic and other therapeutic services) were eligible to be performed on a day-care basis; these spanned the fields of general surgery, orthopaedics, gynaecology, gastroenterology, cardiology, urology, proctology, dermatology, ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology and neurology (1993/6). Day care is paid by HDGs and these are separately defined in a ministerial decree (see section 3.7.1 for information on Hungarian DRGs) (1993/6).

The government also supported the expansion of day-care capacities by means of various projects, the EU structural funds’ sponsorship of infrastructure development and the provision of extra financing for increased cases attended to (in 2003 and 2007). In the 2003 pilot project, eight service providers, five public and three private, were contracted for 16 750 extra cases to be treated over a two-year period between 2004 and 2005 (2003/2). In 2007, 5% of the financial resources freed as a result of the 2007 downsizing of acute inpatient care capacities were reallocated to the provision of day-care services (2007/3). Altogether 104 providers submitted applications to the tender of the NHIFA, and 22 500 HDG points and 66 964 cases were distributed among the 47 winners. In addition, the Ministry of Health[20] distributed extra output volume points (expressed in HDGs) for day-care cases in 2008 from the so-called “ministerial pool” (a certain percentage of the total output volume in a given year has been set aside for the Ministry to distribute at its own discretion). Infrastructural development was also supported by the government with conditional and matching grants, most importantly for the refurbishment of existing polyclinics under the Regional Operative Programmes, and the building of new polyclinics under the Social Infrastructure Operative Programmes of the New Hungary Development Programme, financed by EU structural funds (2006/6). In the former, day care was optional, while in the latter it was a compulsory component. Most of these new capacities are to be operational in 2011.

In addition, the government in power from 2006 to 2010 used special payment arrangements to support day care. Since 1 June 2008, hospitals have been allowed to convert a portion of their billable fee-for-service points (that is, the maximum number of points for which a provider is eligible for SHI financing) for outpatient specialist care to HDG points (2008/3). This measure was not entirely successful, as only a fraction of fee-for-service points was converted (70% and 40% of fee-for-service points remained unused in 2008 and 2009 respectively) (State Audit Office, 2010). As a result of the aforementioned measures, the number and share of day-care cases have been increasing, especially in the past four years. Nevertheless, there is still no specific strategy with exact targets for day care in Hungary, and the proportion of same-day surgery is still very low compared, for example, to the UK, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands (State Audit Office, 2010). Only 10.8% of elective surgical procedures were performed as day cases in 2008 (OECD, 2010). In 2009 a total of 129 469 day-care cases (121.4 cases per 10 000 inhabitants) were reported in Hungary (HCSO, 2010f), and some two-thirds of publicly financed health care providers reported offering day-care services (NHIFA, 2010).

- 20. As of 2010 called the State Secretariat for Healthcare within the Ministry of National Resources. ↰