-

22 March 2024 | Country Update

Changes to the operating conditions of branch pharmacies -

22 November 2023 | Policy Analysis

Concession of institutional (hospital) pharmacies -

22 November 2023 | Country Update

Stricter rules for the distribution of dietary supplements -

21 November 2023 | Policy Analysis

The amount spent on voluntary health fund services has increased greatly -

07 July 2021 | Country Update

New regulations on electronic prescriptions -

29 June 2017 | Policy Analysis

Changes in the pharmaceutical sector from 2011 to 2016 -

30 March 2014 | Country Update

Remuneration of pharmaceutical care -

15 February 2014 | Country Update

Pharmacists increase pharmacy ownership shares to exceed by 25% -

01 January 2014 | Country Update

Pharmacists gain access to health insurance patient records

5.6. Pharmaceutical care

The pharmaceutical industry, from production to marketing, distribution and consumption, is comprehensively regulated in accordance with EU regulations (see section 2.8.4 for more details). There are three groups of actors in the supply chain of pharmaceuticals: producers, wholesalers and retailers. After two major waves of privatization and liberalization over the past 20 years – the first in the early 1990s and the second after 2006 – the pharmaceutical industry was mostly privately owned as of April 2011, with only a small segment of the supply chain in the public sector.

During the communist era, pharmaceutical companies were owned by the state and supplied not just most of the domestic market, but exported to countries of the former socialist bloc. In the early period of economic transition, the market was liberalized and, by the end of 1996, all but one Hungarian pharmaceutical company were privatized, with the state retaining a small share (between 5% and 27%) in three other companies (Antalóczy, 1997). Since then, state ownership has continued to decrease. In 2010 there were close to 200 producers in the market, which by and large can be classified into three groups: (1) companies that have local manufacturing plants in Hungary and typically produce generics; these companies are represented by the Hungarian Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association; (2) large international companies that mainly produce original pharmaceuticals outside Hungary; these companies are represented by the Association of Innovative Pharmaceutical Manufacturers, which has 23 members; and (3) approximately 30 smaller manufacturers of generics without local production. The market share of these three groups, according to the pharmaceutical sub-budget of the HIF, is 23%, 58% and 12%, respectively (Government of the Republic of Hungary, 2010b).

Since the majority of the wholesale and retail industries were privatized in the 1990s, substantial market concentration has taken place. In 2010 three wholesalers covered around 90% of the pharmaceutical trade market: Hungaropharma (between 35% and 40%), Phoenix (40%) and Teva (10%). Another company, Euromedic Pharma, is a major partner of hospital pharmacies (Government of the Republic of Hungary, 2010b). Hungaropharma is owned by the three main Hungarian pharmaceutical manufacturers (Richter Gedeon, Egis and Béres) and, to a small extent, by pharmacies.

The pharmaceutical retail market has two main segments: (1) retail units serving the general public (called open-access public units) and (2) retail units serving inpatient care (called closed-door units). The two segments can and do overlap in everyday practice, for example in inpatient care. Four types of pharmacies are distinguished by law (2006/8):

- Public (open-access) pharmacies (called community pharmacies in the academic literature). This is a general type of pharmacy that provides the full scope of pharmaceutical services, dispensing prescription-only medicines, magistral preparations, non-prescription (over-the-counter) medicines and nutritional supplements to the public. It must be managed by a pharmacist with the right to operate a pharmacy and to carry out managerial functions. A range of staffing, material and IT requirements are specified by law (2007/3).

- Branch pharmacy. This type of pharmacy operates as an affiliate unit of a community pharmacy and can be established in areas without public pharmacies. Professional requirements and other standards are less stringent for these pharmacies.

- Institutional (hospital) pharmacy. The main function of this type of pharmacy is to supply medicinal products for inpatient care in a hospital, but hospital pharmacies can have community pharmaceutical retail units, as well. Originally, these units were classified as restricted (or “closed access”) pharmacies because they were allowed to serve only discharged patients and hospital staff. These restrictions were eliminated, however, in 2006 (2006/8).

- Single-handed pharmacies (pharmacy run by a physician). These are actually not pharmacies in the strict sense of the word, but rather a service provided by a family doctor whose office is located in a remote area lacking a community or branch pharmacy. Family doctors are allowed to supply pharmaceuticals only to patients who are enrolled in their registry, with the exception of emergency cases. Single-handed pharmacies run by physicians have contracts with community pharmacies in order to administer the pharmaceuticals prescribed and sold.

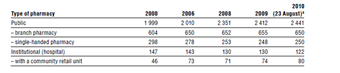

The number and main types of pharmacies are shown in Table5.1.

Table5.1

In addition to the types of pharmacies shown in Table5.1, there are three other categories of pharmaceutical retail (Government of the Republic of Hungary, 2010b). First, the over-the-counter market was liberalized in 2006 by allowing the sale of certain over-the-counter drugs outside of pharmacies (2006/8). In 2010, about 470 types of over-the-counter medicines were available in about 600 retail units (mostly petrol stations, supermarkets, drug stores and beauty shops); only 1% of total over-the-counter retail sales took place in such locations, however. Second, through the active inpatient care sub-budget of the HIF, the NHIFA is the direct purchaser of certain very expensive drugs (e.g. target therapies in oncology such as trastuzumab, bevacizumab and pemetrexed), which are supplied to hospitals by the manufacturers on a contractual basis, as part of which the NHIFA stipulates the number of patients that can be treated. Approximately 3–4% of the pharmaceutical sub-budget of the HIF is spent this way. Third, only a very small fraction of pharmaceutical retail takes place through the internet and home delivery, which is still operated by pharmacies.

Before 2006 the ownership and market structure of pharmaceutical retail was developed based on the ethical model of corporate responsibility. Privatization was guided by Act LIV of 1994 on the Establishment and Rules of Operation of Pharmacies, according to which only self-employed private entrepreneurs and limited partnerships were allowed to operate community pharmacies, with the additional requirement that the unlimited liability partners of the limited partnerships must be pharmacists with at least a 25% share (Article 36). Community pharmacies had to be established and managed by pharmacists with a special licence, the so-called personal right (személyi jog) (Article 15), a concept similar to the “practice right” in primary care (see section 5.3). In partnerships, one of the unlimited liability partners had to be a pharmacist in possession of this special licence (Article 29). With these measures, the government aimed to ensure that pharmacists had a decisive role in the management of community pharmacies and that the pharmaceutical retail system would not be dominated by profit-making investment interests alone. By the end of 1997, all previously state-owned pharmacies serving the general public had been privatized according to this model (HCSO, 1999).

Act LIV of 1994 also restricted the establishment of new pharmacies by requiring a minimum of 5000 inhabitants per community pharmacy, and a minimum distance of 300 metres (and 250 metres for towns with a population of more than 100 000) between new and existing pharmacies, from which the Office of the Chief Medical Officer (see section 2.3.3) was allowed to deviate only with the approval of the Chamber of Pharmacists (see section 2.3.10) (Article 5). The NPHMOS designated an indicative catchment area as part of the registration and licensing system, but this did not restrict the choice of consumers in any way (Article 6). Table5.1 shows that this model contained the number of new pharmacies very effectively: between 2000 and 2006 only a handful of new pharmacies were established. The government in power from 1998 to 2002 strengthened the pharmacist-owned retail system by increasing the minimum ownership share of pharmacists from 25% to 50% (to be achieved by 31 December 2006) and excluding pharmaceutical manufacturers and wholesalers from ownership (2001/10). The plans were not realized, however, because the government in power from 2006 to 2010 rewrote the respective regulations based on a liberal model of corporate responsibility, eliminating most of the restrictions on ownership (no limitations regarding the type of business entity, no minimum share of pharmacists stipulated, manufacturers and wholesalers not excluded, pharmacy chains not prohibited), and relaxing the criteria for establishing new pharmacies (no population and distance restrictions for new pharmacies undertaking the provision of extra services for at least three years, such as longer opening hours, night duty, internet-based ordering and home delivery) (2006/8).

The new regulations entirely changed the dynamics of the pharmaceutical retail market. Between 2006 and 2010, the share of community pharmacies increased by more than 20% due to a higher concentration in cities and larger villages. At the same time, the supply for villages with less than 1000 inhabitants worsened. Moreover, pharmacy staff were unable to cope with the increased number of retail units and longer opening hours. As a result of the relaxed ownership regulations, both horizontal (the establishment of pharmacy chains) and vertical (acquisition of ownership by manufacturers and wholesalers) integration took place. It is estimated that in 2010 some 15–20% of pharmacies operated in chains (Government of the Republic of Hungary, 2010b).

The government that took office in 2010 has returned to the original, ethical model of corporate responsibility. In June 2010 the licensing of new pharmacies was suspended and further mergers were banned (2010/9). Moreover, in December 2010 a new act was passed endorsing the gradual reacquisition of ownership by pharmacists: Act CLXXIII of 2010 on the Amendment of Certain Health Care Related Acts brings the operation of pharmacies under the personal responsibility of pharmacists in order to enable them to contribute to efficient therapies and prevention programmes and to support healthy lifestyles (Articles 77 and 83). The minimum share of pharmacists’ ownership in already functioning pharmacies must now reach 25% by 2014 and 50% by 2017 (Article 84). Actors in the pharmaceutical supply chain are not allowed to own newly established pharmacies, and mergers are banned for chains that consist of more than four pharmacies (Article 84). As for the pharmacies already owned by wholesalers, the shares must be adapted to the stipulated limits, but currently operating pharmacy chains may be maintained. As of May 2011, no offshore company will be allowed to hold shares in pharmacies (Article 87).

The demographic and geographical criteria for establishing new pharmacies have also been changed. A community pharmacy can only be established based on national tenders. In the case of municipalities with less than 50 000 inhabitants, the minimum demographic criterion is 4500 persons per pharmacy (including the new one) and the minimal geographical distance between pharmacies is set at 300 metres. In the case of bigger towns, the numbers are 4000 persons and 250 metres. The restrictions do not apply if the given municipality has no established pharmacy (Article 69). During the evaluation of tenders, priority is given to pharmacies that intend to provide additional services, such as longer opening hours, out-of-hours services, running a branch pharmacy or providing home delivery (Article 68). These changes aim to ensure that new pharmacies meet local needs and contribute additional services. The new provisions also regulate pharmacies’ promotional activities, prohibiting such activities for reimbursed medicines and restricting them to the provision of health care services in the case of non-reimbursed drugs (Article 59).

In 2009 a total of 5301 pharmacists and 7536 pharmaceutical assistants worked in community pharmacies, whereas another 430 pharmacists and 790 assistants worked in hospital pharmacies (HCSO, 2010f). According to the concept of pharmaceutical care introduced in 2009 (2008/9), pharmacists are expected to provide health information and prevention activities, supervise and monitor drug treatment, work to minimize side effects and avoid harmful drug interactions (2009/6). It is estimated that about 15% of pharmacies in 2010 took part in some form of pharmaceutical care programme (Government of the Republic of Hungary, 2010b).

The regulation and supervision of the pharmaceutical supply system is shared between the Ministry of National Resources (responsible for the regulatory framework), the National Institute of Pharmacy (responsible for manufacturers, wholesale distributors and clinical trials), the NPHMOS (responsible for retail trade – that is, pharmacies; see also section 5.1), and the NHIFA (responsible for HIF coverage of pharmaceuticals).

The manufacturing of pharmaceuticals for human use must be authorized and the products must be granted marketing authorization (that is, a licence) by the National Institute of Pharmacy. The price that is ultimately to be used as the basis for subsidy (that is, the agreed price) is subject to a negotiation process, whereas the wholesale and retail margins are regulated. The price of over-the-counter pharmaceuticals is not regulated. Hospitals buy pharmaceuticals directly from wholesalers or are supplied directly by the manufacturers, which are contracted by the NHIFA, as for example is the case for special, very costly pharmaceuticals. Prices are negotiable but may not exceed the wholesale price set in the case of subsidized pharmaceuticals (2007/1).

The HIF covers some pharmaceuticals partially and some in full. The process of including pharmaceuticals in the benefits package follows the requirements of the Transparency Directive of the European Commission (89/105/EEC) introduced in 2004 (see section 2.8.4 for more details) (2004/4). In 2010, there were 5513 products on the list for the drug benefits package, but not all of them were subsidized. The method for determining the extent of subsidies and user fees depend on several factors, including the severity of the condition, the indication and the type of prescription and pharmaceutical. In most cases, patients must pay user fees for prescribed pharmaceuticals in outpatient care, but inpatient care includes the cost of pharmaceuticals (at least according to the regulations) (see section 2.8.4).

The rules for prescribing pharmaceuticals were set forth in 2004 and 2005. In principle, every physician and dentist is entitled to prescribe pharmaceuticals by using their personal stamp along with their signature at the bottom of a prescription (2005/3). Under the so-called pro familia label, physicians can prescribe pharmaceuticals for themselves and their immediate family members (2004/5). Certain medicinal products, however, can be prescribed only by specialists. Family doctors can prescribe these pharmaceuticals (typically for chronic diseases) for up to three months if the relevant specialist has endorsed the use of pharmaceutical treatment for a given patient (2005/4). Only one pharmaceutical is allowed per prescription (2004/5). The prescription must include information about the patient and the prescriber, the name of the pharmaceutical or its active ingredient, its quantity and its dosage (indicated daily dose) (2004/5). The prescribed quantity may not exceed the quantity necessary for one month’s treatment, with the exception of patients with chronic conditions to whom pharmaceuticals can be prescribed for up to three months or, in exceptional cases, up to one year (2004/5).

There are two major types of reimbursement: indication-related and fixed. In the first category, the indication for a certain substance needs to be confirmed by a specialist. Some pharmaceuticals for less severe chronic conditions are covered up to 90%, 70% or 50% of the agreed retail price, while medications for the more severe, life-threatening diseases are covered 100% (however, in most cases a minimum patient co-payment, the so-called package fee, of approximately €1 must still be paid). In the second category, all indications determined in the licence of a medication are covered, either up to a fixed amount (through the reference pricing system) or on a percentage basis (80%, 55% or 25% of the agreed price). The reference pricing system is used for products with identical active ingredients or similar therapeutic effects. In the case of products with identical active ingredients, the basis for reimbursement is the daily treatment cost of the reference product, which is the product available on the market for at least six months with the lowest daily treatment cost and with a market share exceeding 1% (as expressed in days of treatment). All pharmaceuticals containing the same active ingredient receive the same subsidy per daily dose. The reference pricing system also applies to products with different active ingredients but similar therapeutic effects (2004/4). Further information on reimbursement can be found in section 2.8.4.

There is a system of exemptions from user charges for pharmaceuticals, medical aids and prostheses, and rehabilitation services for social service beneficiaries (1993/1). When this system was introduced, eligible individuals received all pharmaceuticals on a special list free of charge, with no consumption or spending limits. In 2006 the government introduced new rules to tackle abuse of the system. Eligible individuals are now granted a monthly personal budget of up to HUF 12 000 (about €45) to cover user charges on recurrent health expenditure associated with chronic diseases; these individuals also have an addition budget of HUF 6000 (about €24) for acute problems (2005/8). The range of accessible medicines is no longer restricted, but any spending above the budget ceiling must be paid out-of-pocket. Entitlement to user charge exemption can be direct (for example, for abandoned children, or for people on regular social cash benefits or on disability pensions), or means-tested (that is, based on patient household income and pharmaceutical expenditure) (1993/1).

Pharmaceutical expenditure in Hungary has three main components: (1) SHI subsidies for pharmaceuticals prescribed in the outpatient care setting, (2) private (mainly OOP) spending on pharmaceuticals prescribed in the outpatient setting, and (3) hospital spending on pharmaceuticals as part of inpatient care that is covered by the HIF (the amount of privately funded inpatient care is negligible). Detailed information on financing can be found in the corresponding sections of Chapter 3. Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durables in 2007 was $434 at PPP per capita, which was slightly below the OECD average of $461 (also at PPP). It is important to note that this figure includes user charges, but does not include expenditure on pharmaceuticals prescribed in the inpatient care setting, which makes international comparisons difficult. The share of public expenditure on pharmaceuticals in 2007 was 58.5%, which is close to the OECD average (57.7%); this being said, the range for this indicator was very wide among the OECD countries, from 21.3% for Mexico to 83.3% for Luxembourg. Between 2001 and 2006 the share of public expenditure on pharmaceuticals in Hungary rose from 61.2% to 67.2%. This upward trend was reversed by the cost-containment and cost-shifting measures of the government in power between 2006 and 2010 (2006/8).

An analysis of pharmaceutical consumption shows that almost two-thirds of spending from the pharmaceutical sub-budget of the HIF was attributable to three main treatment groups: cardiovascular (26%, or HUF 71 billion, about €280 million), oncological (23%, or HUF 64 billion – about €253 million) and neurological/psychiatric (14%, or HUF 38 billion – about €150 million) (Government of the Republic of Hungary, 2010b). The international comparison of defined daily dose (DDD) rates confirms this pattern. Among those countries for which data were available in 2006, there were three areas in which Hungary deviated significantly from the OECD averages: pharmaceuticals for cardiovascular disease (Hungary 613 DDDs vs OECD 456 DDDs), for hypertension (Hungary 23.7 DDDs, the highest among OECD countries, vs. OECD 7.8 DDDs) and anxiety disorders (Hungary 53.1 DDDs vs. OECD 30.7 DDDs) (OECD, 2009b).

On 4 July 2023, the Hungarian Parliament amended Act XCVIII of 2006, which outlines the general rules for the safe and economical supply of medicines and medical aids, as well as the distribution of medicines.

With the amendment, the government introduced the concept of a “unified institutional pharmacy system” to improve, according to the government, the operational efficiency of institutional pharmacies through investments, including those enabling individual medication administration. Non-state-run hospitals can voluntarily opt into the joint institutional pharmacy system. The proclaimed focus is reducing expenses in the procurement of medicines without compromising patient care. The government will later develop the regulation for a unified institutional pharmacy system, emphasizing the efficiency of concession operations and how service providers can provide better services.

The Hungarian Chamber of Pharmacists (MGYK) has criticized outsourcing, expressing concerns about the entry of a potentially new, unregulated major player in the Hungarian pharmacy market. They fear that a future tender winner can essentially be authorized to establish and operate a chain of pharmacies, providing direct medicine supply to the public, which can be harmful to the whole system. For instance, the MGYK questions whether such a player would be motivated to ensure the unprofitable administration of high-value pharmaceuticals (for example, pharmaceuticals financed with individual fairness).

The pharmacy profession is also concerned about the impact on hospital pharmacists. Over the past decade, efforts have been made to make the career of a hospital pharmacist attractive, but this progress could erode quickly, especially if the opportunities to work with particular products, such as high-value and rarely sought prescribed pharmaceuticals, diminish for financial reasons.

The dietary supplements market in Hungary has undergone significant changes over the past years. According to the explanation of an amendment to the Act XLVI of 2008 on the food chain and its official supervision, adopted on 4 July 2023, there has been an annual increase in product variety and sales volume. As it highlights, there is an increase in health risks associated with excessive consumption of certain vitamins or minerals and improper product combinations. Therefore, the amendment grants the responsible minister the authority to issue a decree establishing a list of dietary supplements restricted to sale in pharmacies or shops that comply with the conditions of the given decree. Although the detailed rules were expected by September 2023, the adoption process is still ongoing. Currently, the specific products under consideration are undergoing professional consultation.

The Hungarian Chamber of Pharmacists (MGYK) has long advocated for stricter regulations, welcoming the tighter distribution framework. As the government, MGYK emphasizes the importance of pharmacists being aware of patients’ use of supplements alongside prescribed drugs, not only due to potential interactions but also because some supplements closely resemble pharmaceuticals in composition and expected effects. MGYK’s president also notes the potential economic benefits, highlighting additional traffic, which is particularly beneficial for small and medium-sized rural pharmacies.

Act XCVI of 1993 on Voluntary Mutual Health Funds created Hungary’s legal framework for complementary insurance schemes. However, in 2003, the government abolished the risk-pooling element of the system. Currently, the system operates as a pure medical savings account (MSA) scheme (see Section 3.5 in the 2011 Hungarian HiT).

By the end of the second quarter of 2023, Hungary had 16 voluntary health funds, covering almost 1.1 million residents, an increase of 33,000 members compared to the end of last year. An increasing number of people pay out of pocket for private health services due to difficulties accessing public care (for example, long waiting lists). Those contributing through a health fund are entitled to a tax refund of 20% of their payment, with a maximum of HUF 150,000 (€395) per year.

According to recent data from the National Bank of Hungary (MNB), voluntary health fund services saw a 26% increase in the first half of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022, totaling HUF 38.86 billion (around €102 million). Notably, expenditures for supplementing or replacing social security health services (for example, private doctor, diagnostics, etc.) rose by 34%, now constituting 40% of all health fund expenditures, up from 19% a decade ago. Pharmaceutical expenditure increased by 23% to HUF 15 billion (around €40 million), while expenses for medical aids rose by 23% to HUF 5.5 billion (€14.5 million).

The soaring expenses (and payments) pose a significant access barrier for the population. A survey conducted by the Premium Health Fund, with more than 10 000 participants, investigated how fund members experienced the negative economic changes over the past year. The findings revealed that while 45% reported no change in their financial situation, 40% experienced a deterioration in their standard of living. Despite attempts to save, 33% had to increase family healthcare expenses. Participants cut back spending on food supplements (37%), private doctors (34%), and healthy eating (29%). Two-thirds of respondents reported unmet needs due to financial difficulties. While most people postponed dental treatments (32%), people also missed private medical appointments, diagnostic procedures, and physical therapy.

According to the survey, the majority of respondents use private medical care. While some find these increasingly expensive, leading them to prefer public healthcare, more are forced to use private doctors due to limited access to state-funded care.

The survey data indicates a negative shift in patients’ perceptions of the accessibility of public healthcare. Meanwhile, the continuous decrease in purchasing power limits their ability to access appropriate care through private providers. These factors can result in long-term adverse health and pose prolonged challenges for the healthcare system.

References

https://statisztika.mnb.hu/publikacios-temak/felugyeleti-statisztikak/penztarak/penztarak-idosorai

https://azenpenzem.hu/cikkek/kenyszerit-az-allam-hogy-maganorvosra-koltsunk/9624

https://bank360.hu/blog/valsagban-elozo-egeszsegpenztarak

https://forbes.hu/penz/lepipalja-a-nyugdijkasszakat-az-egeszsegpenztar-erre-koltenek-a-magyarok

https://index.hu/belfold/2023/09/03/egeszsegugy-magyarok-sporolas-ongondoskodas-kutatas

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, certain restrictions on the electronic prescription of pharmaceuticals have been removed, such as printed prescription proofs and authorizations. Since March 2020, ePrescriptions have been available and can be redeemed by anyone on behalf of the patient. The person who picks up the pharmaceutical should communicate the patient’s social insurance identification number and credibly prove their personal identification details.

The government, which took power in 2010, had two main policies determining the supply of pharmaceuticals in the Hungarian health system. First, as part of the government efforts to manage the 2008 financial crisis, including the fiscal deficit and the public debt, pharmaceutical subsidies had become the prime target for cost savings and budget cuts. Second, the government pledged to reverse the liberalization of retail trade, implemented by the previous government of 2006-2010, in line with the ethical model of the pharmacy system and with the concept of pharmaceutical care.

As part of the so-called Széll Kálmán stabilization and austerity plan, there have been two waves of measures targeting the pharmaceutical sub-budget of the HIF. The first austerity package was approved by the government on 1st of March 2011. On the revenue side, the clawback of pharmaceutical expenditures from pharmaceutical companies increased from 12% to 20%, the head tax on sales agents doubled from 5 to 10 million HUF (16 400- 33 000 EUR), and the subsidy volume contracts had been revised, which decreased the upper limit for the subsidies to be paid by the NHIFA. On the expenditure side, measures aimed at the expansion of the use of generics with a generic program (fixed subsidies, financial incentives for prescriptions and substitution, promotion of first generics, etc) and the revision of certain therapeutic areas, including combination medications and cholesterol lowering drugs. In April 2012 the second Széll Kálmán Plan (2.0) introduced a wide range of further measures, including among others the concept of outcome-based financing, the increase of competition with blind bidding, the revision of the co-payment exemption scheme, the compulsory provision of information for patients about generic substitution, the expansion of the central procurement of medicines partly by the NHIFA (the increase of the number of drugs under itemised financing from 6 in 2011 to 36 in 2015) and by the GYEMSZI, the new owner of hospitals on behalf of the central government (coordination of the drug procurement of hospitals), and the concept of compliance-based subsidisation of pharmaceuticals. This latter was implemented in the case of analogue insulin in July 2012. Patient compliance was measured by the level of HbA1c, which had to be below 8% in the previous half a year verified by two independent tests for the patient to be eligible for higher subsidy, but the criteria were somewhat mitigated in April 2013 (only for type II diabetics with a full year measurement period, and two tests to be below 8% out of three). As a result of all the actually implemented interventions the pharmaceutical sub-budget of the HIF diminished in nominal terms from 357 billion HUF (1.1 billion EUR) in 2010 to 302 billion HUF (0.99 billion EUR) in 2014, according to State Treasury data.

Regarding the framework of pharmaceutical retail trade, the government of 2010-2014 had envisaged a health service provider role for pharmacies to achieve efficiency gains instead of emphasising the trading aspects of the distribution of medicines and trying to increase competition among a wider scope of drug retailers (such as gas stations and supermarkets). In order to revert to the earlier ethical model, the government restricted the scope of potential owners of new pharmacies by excluding pharmaceutical and wholesale trading companies and they could only be opened with a pharmacist having over 50% ownership share. For the already operating pharmacies the same criteria applies, which had to be met by 1 January 2017. To support the reacquisition of ownership shares, the government launched the so-called Pharmacy Credit Program, in the frame of which pharmacists could borrow with below market interest rates and a minimum of 10% own share.

Other important measures include the introduction, regulation and financing of pharmaceutical care. Decree No. 52/2012. (XII.27.) EMMI of the minister for human capacities defined a basic package of pharmaceutical care activities, whose implementation has been supported with a yearly budget of 4.5 billion HUF (1.5 billion EUR) since 2013, while a pharmaceutical care guideline was issued on the 1st of April 2013. Further, in 2015, a new requirement was implemented that pharmacies could only be managed by pharmacists with an appropriate specialisation. Unfortunately, there has been no study conducted yet regarding the impact of these measures on the performance of the health system.

Authors

References

Government Resolution No. 1226/2011. (VI. 30.) Korm.

Act LXXXI of 2011 on the Amendment of Various Health Care Related Acts

http://ecopedia.hu/szell-kalman-terv

Széll Kálmán Terv 2.0, pp.200-203

MÉRTÉK health system performance report for 2013-2015.

Decree No. 31/2013. (IV.30.) EMMI of the minister for human capacities

Semmelweis Plan

https://www.mfb.hu/tevekenyseg/maganszemelyek/patika-hitelprogram

Decree No. 52/2012. (XII.27.) EMMI of the minister for human capacities(amending Decree No. 44/2004. (IV. 28.) ESzCsM)

The health policy of the government of 2010-2014 aimed at returning to the ethical model of pharmaceutical retail trade, but also redefining the role of pharmacies and pharmacists in the delivery of health services. According to this model of pharmaceutical care, pharmacists are delivering a special type of health service related to the proper use of medicines, e.g. by checking drug interactions, active ingredients and regularity of drug use by chronic patients. As a result, pharmacies are considered health care providers and not sales units. While pharmacies are still reimbursed on the basis of retail price margins, an increasing part of their revenue comes from the National Health Insurance Fund Administration as a payment for pharmaceutical care. NHIFA payments are commensurate with the number of prescriptions served, but pharmacies receiving fewer prescriptions are paid an increased fee per prescription compared to those with a higher turnover. The available budget for the remuneration of pharmaceutical care is EUR 145,000.

Authors

An amendment to Act No. XLVII of 1997 on the protection of personal health data, which took effect on 1 April 2013, allows pharmacists access to prescription medication data for the preceding 12 months from the National Health Insurance Fund Administration. Data related to sexual and mental diseases have been excluded; they are only available if not explicitly prohibited by the patient and only when the medication was directly dispensed to the patient themselves. These regulations aim to assist pharmacists in generic substitution or in finding the right medicinal product in case of active substance prescription, but also to detect parallel dispensing and identify drug interactions or other adverse effects.