-

14 March 2025 | Country Update

Regulatory changes to the Hungarian national eHealth infrastructure aim to optimize access to outpatient care -

17 May 2023 | Country Update

A new oncology centre has opened in Salgótarján -

14 December 2018 | Country Update

More Details about the Healthy Budapest Program -

11 December 2018 | Country Update

New or renovated accommodations for nurses -

24 October 2018 | Country Update

Update on the Healthy Budapest Program -

08 October 2018 | Country Update

1 billion HUF budget for ultrasound machines -

27 August 2018 | Country Update

Additional 167 billion HUF for hospitals -

27 September 2016 | Country Update

eHealth developments in Hungary

4.1. Physical resources

At Szent Lázár County Hospital in the city of Salgótarján, in Nógrád County, a radiotherapy centre equipped with state-of-the-art technology opened in April 2023 after five years of planning. This is Hungary’s 14th radiotherapy centre and marks a significant upgrade for the oncology ward of the county hospital, which has been operating for more than ten years.

The new centre offers the full range of available treatment options, including radiotherapy and endovascular interventions, as well as significantly improved conditions for oncological surgery. It also has a vascular staining laboratory, which is set to contribute to the improved and proper treatment of patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

The burden of both cardiovascular diseases and cancer are relatively high in Hungary. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the country, while, in 2019, Hungary registered the highest cancer mortality rate among EU member states.

Authors

In the past decade, Budapest was left behind in healthcare developments compared to the countryside, as the previous EU funding cycle provided 500 billion HUF (1.6 billion EUR) in investments in regions outside the Central Hungarian region. Therefore, during the next 4-5 years, the health sector will aim to close the gap.

The Healthy Budapest Program (EBP) concentrates most of this healthcare development with the biggest, 700 billion HUF budget (2.2 billion EUR). Three central hospitals will be established within this framework, but the most prominent will be the newly built South Buda Institution. The agenda of the EBP will also include the development of national institutes and no hospitals or clinics will be excluded from the program.

According to Péter Cserháti- head of the EBP, the Magyar Idők (governmental newspaper) reported that the EBP will last 10 years and will run approximately until 2026. During this period four major processes will occur in parallel: purchasing equipment for inpatient and outpatient care, preparing energy modernization, renovating the majority of regional specialised clinics, and planning the renewal and reorganization of hospitals.

Authors

Hungary will spend 8.5 billion HUF (27 million EUR) on new accommodation for nurses that will be built in Kaposvár, Kecskemét, Szombathely and Nyíregyháza. In 12 other locations, the existing accommodations will be renovated until 2020. Additionally, in 13 county and city hospitals the housing conditions for healthcare professionals will be modernized, as announced by Miklós Kásler, the Minister of Human Capacities. The Minister emphasised these accommodations will help keep the good healthcare professionals in the country and show a more attractive career path for future generations. The four newly built accommodations for nurses will add 386 new places, while after the renovation a total of 1209 places will be modernized.

Authors

References

In July a government decree was published in the Hungarian Official Gazette aiming at the development of outpatient specialist providers with more than 7 billion HUF until 2021 (21 Mill EUR). This is part of the so-called “Healthy Budapest Program”, which started a year ago.

In October, the Minister of the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister announced, that the Healthy Budapest Program would include not only three, but four central hospitals, as the St John Hospital would also take a special role in the new system by covering the inhabitants of the Northern Buda region of Budapest. The Healthy Budapest Program aims to optimize patient pathways in Budapest. The other three central hospitals will be the Military Hospital (Honvéd Kórház), covering the Northern Pest region, the unified St. László and St. István Hospital, covering the Southern Pest region and the South Buda Centrum Hospital, covering the Southern Buda region, which will be a new hospital.

Authors

References

Publicly funded institutions are able to apply for funds to purchase new ultrasound machines from a one billion HUF budget-announced Dr. Zoltán Ónodi-Szűcs, appointed Minister of State for Health.

In the application system the Secretariat of State for

Health accounts for different sizes and functions of each provider and

each provider can apply for up to five machines (10 million HUF/machine)

at the same time.

Authors

The current 21 Hungarian and European Union tenders are amounting to 167 billion HUF (516 Mill EUR) budget to improve the infrastructure of hospitals, said the Director-General of the National Healthcare Service Centre (ÁEEK). Within the framework of the EU funded Social Infrastructure Operational Program (TIOP), 450 billion HUF was spent on the modernization of rural hospitals since 2009. Hospitals in the Central Hungarian Region were not eligible, so the next step has to be the refurbishment of the Budapest hospitals (in the frame of the “Healthy Budapest Program”). Future developments are concentrated on Budapest, but rural health institutions will not remain without funding.

Authors

As part of the project on developing electronic public administration, Hungary is expected to launch an eHealth system in the second half of 2016, including modules such as ePrescription and eReferral, in the mainframe of the so-called Electronic Health Service Space.

In April 2016 a test period will begin, with the participation of pharmacies, outpatient service providers, hospitals and other health service providers. It is expected that the current, paper-based system will run parallel to the electronic system. At the end of the year the system will be made accessible to all provider institutions and participation will be made obligatory in 2017. Thus, the paper-based documentation will be fully replaced by the new eHealth system in the long run.

Authors

4.1.1. Capital stock and investments

According to statistics from the HCSO, Hungary had a total of 175 hospitals in 2009. Altogether, these hospitals had 71 489 beds, of which 71 064 were in operation (HCSO, 2010d). These statistics, which are based on the NHIFA annual report for 2009, require some clarification (NHIFA, 2010).

First, the total number of hospitals does not include institutions without an NHIFA contract (i.e. the one private, profit-making hospital and one of the two hospitals owned by the Ministry of Public Administration and Justice, the so-called prison hospital at Tököl). Adding the 708 beds operated by these two institutions to the total number of beds cited above brings the total inpatient capacity in 2009 up to 72 197 beds.

Second, although same-day surgery is considered acute inpatient care in Hungary and is paid through HDGs, it can also be performed by outpatient specialists (see section 5.4). As a result, the 175 or 177 hospitals cited above include 22 polyclinics that do not have any contracted inpatient capacities.

Third, according to the minimum standards of health service provision set by the Minister of Health (now known as the State Minister for Health) in 1996 and 1997, inpatient care providers with less than 80 beds should not be classified as hospitals (2003/15). There were 30 such providers in 2009.

Thus, if we exclude the 22 polyclinics, as well as the 30 providers with less than 80 beds, there were in reality only 125 hospitals that year. Here, it is important to note that so-called daytime hospitals are also not included in the NHIFA report; these hospitals represent an emerging form of care that is currently used mainly in the long-term treatment of psychiatric patients (see section 5.7). The care these hospitals provide should not be confused with same-day surgery.

Table4.1 provides simple descriptive statistics on the number of 155 inpatient care providers and their capacities. The average capacity was 470 beds, and the total number of beds operated by each provider ranged from 10 to 2166. The largest provider was Semmelweis University in Budapest, and the smallest were two hospice and chronic care providers, each of which had 10 beds. About 70% of all providers had fewer than 500 beds. Larger hospitals (that is, hospitals with more than 1000 beds) include four universities with medical faculties, four municipal hospitals, the Military Hospital in Budapest, 13 large county hospitals, and a large municipal hospital in Borsod county. Six inpatient care providers had only acute beds, whereas 45 had only chronic capacities (although 8 of these 45 also provided same-day elective surgery). The rest had a mixed profile with both acute and chronic beds. The average acute capacity was 415 beds, while the corresponding figure for chronic care was 186 beds in 2009. The largest chronic care provider in 2009 was a municipal hospital in Budapest, with 795 chronic beds.

Table4.1

In 2009 more than 26% of inpatient care capacity was concentrated in Budapest, which had 108.8 beds per 10 000 population, or about 50% more than the nationwide average (Table4.2). Even though there had been some excess capacity in Budapest in the early 1990s, these figures no longer represent unjustified disparities in the geographical distribution of hospital beds for two reasons: first, Budapest serves the population of the surrounding counties as well (mainly Pest county, but to a lesser extent also Komárom-Esztergom, Fejér, Nógrád and Heves counties). When Pest county is taken into account, which together with Budapest forms the region known as Central Hungary, the number of hospital beds per 10 000 population exceeded the nationwide average by only 6% in 2009. Second, Budapest accommodates the majority of care capacities at the highest level of specialization (for example, at the National Institutes of Health), and the institutions at this level have a catchment area that encompasses the entire country.

Table 4.2

At the regional level, geographic inequalities have generally decreased over the past 20 years, although this does not mean that capacity currently matches health care needs perfectly. The Southern Great Plain region showed the greatest deviation: in 2009, its capacity in terms of hospital beds was about 10% lower than the country average and the health status of its population was worse than the nationwide average. Although capacity in the Northern Great Plain region deviated less from the nationwide average, the health status of the population in this region was even worse than that in the Southern Great Plain region. It is important to note that whereas both the Northern Hungary and the Southern Transdanubia regions were above the country average in terms of hospital beds, the health status of their populations was substantially worse than the country average, which also implies regional disparities (HCSO, 2010a). Even though inpatient care capacity shows even larger disparities at the county level, this is not necessarily a source of concern, given that the utilization of health services is not confined by the geographical borders of the counties.

The general condition of the hospital infrastructure has been an issue for some time because sufficient public resources have never been invested in the refurbishment of buildings and equipment. A typical hospital has a large number of separate, often old and outdated buildings, usually located on different sites. According to a survey carried out in 2004 with the participation of about 50% of hospitals (that is, 75 providers with altogether 44 499 beds), the mean age of hospital buildings was 50.5 years (with a range of 45 to 62 years), and the average number of buildings per hospital was 22 (Papp & Eőry, 2004). Furthermore, in certain regions there were as few as 18 to 25 beds per building. In 2005 the 109 municipal hospitals had 3157 buildings (29 per hospital) on 337 sites (on average more than three sites per hospital) (State Audit Office, 2005). The 2004 survey estimated that over HUF 187 billion (€760 million) would have been needed at the time to modernize the buildings of the participating hospitals, whereas only HUF 11 billion (€41.7 million) had actually been spent on reconstruction over the three previous years. Of the latter amount, more than 40% came from central government grants, less than 30% from the owners (that is, local governments), about 14% from providers’ own resources, and the remainder from other grants and donations (Papp & Eőry, 2004). The State Audit Office of Hungary, which examined the use of central government grants for hospital reconstruction in 2005, found that the 22 surveyed hospitals had spent HUF 3.4 billion (€13.5 million) on building renovations between 1996 and 2004, which corresponded to an average of 0.7% of the gross book value of their real estate per year (State Audit Office, 2005).

The Directorate of Medical and Hospital Engineering of the Institute for Healthcare Quality Improvement and Hospital Engineering (formerly the Institute of Medical and Hospital Engineering) keeps a registry of real estate and of the energy use of inpatient care providers. Both publicly and privately owned hospitals are obliged to participate in collecting data every three years on their various sites, buildings and organizational units, as well as on energy procurement and use. Even though the database and various reports on hospital facilities are used by the State Secretariat of Healthcare and other governmental organizations, the State Audit Office regularly points out that health care investments have not been based on a comprehensive sector development strategy and that investment decisions have lacked coordination as a result, fostering parallel development, especially in the area of medical equipment. Because investment decisions have been guided instead by local economic interests, the structural transformation necessary to meet population health care needs and ensure the long-term sustainability of health care capacities has not been prioritized (State Audit Office, 2005).

Since the introduction of the purchaser–provider split model in Hungary, the financing of health services has been based on the separation of capital and recurrent expenditure. Whereas HIF financing covers recurrent expenditure only (1992/8, 1997/19), capital expenditure (both maintenance and new investments) is the responsibility of the owners of health care facilities, based on the principle known as the maintenance obligation (1997/20). This system of separate financing for capital and recurrent costs applies to the vast majority of health services, including inpatient and ambulatory care. The only exceptions are certain services such as public health and emergency transportation, which are financed entirely from the government budget (see sections 5.1 and 5.5). In theory, the owners of health care facilities (mainly the local governments of municipalities and of counties, and to a lesser extent the central government and private entities) must finance the investment in and maintenance of infrastructure, buildings and equipment from other sources. In practice, however, hospitals have used NHIFA revenue for investment purposes, and in 2000 the government decided to take a less rigid stance and relax regulations in this regard (1999/12). It is not surprising that providers have been allowed to use NHIFA revenue to cover capital expenditure, since the maintenance obligation has placed a substantial burden on local governments, which usually have a relatively weak revenue base and are in need of central government support.

Local governments have four other sources of revenue for investment and capital stock maintenance: (1) transfers of national tax revenue (for example, part of the personal income tax), (2) local taxes, (3) central government grants in the form of earmarked and target subsidies and (4) other conditional capital grants from national sources (mainly the Ministry of National Resources) and international sources (mainly EU structural funds). In principle, local governments should use the first two sources to cover the capital expenditure on health care facilities. In practice, however, only a few local governments can afford to pay for expensive medical equipment or for refurbishing hospital wings or entire buildings. The central government has thus offered conditional and matching grants under Act LXXXIX of 1992 on the System of Earmarked and Target Subsidies for Local Governments (option 3 above), which also determines the components of the system and the application process.

The first component is a conditional capital grant (earmarked subsidy) for large-scale projects, usually for the renovation or extension of existing buildings with a cost exceeding HUF 250 million (€900 000). Its upper limit and local contribution share are not specified (2006/2). Local governments submit project proposals to the ministry responsible for local governments (as of June 2010 the Ministry of Interior), which makes a priority list while taking into account recommendations from the relevant ministry (for example, in the case of health care projects, the ministry responsible for health, that is, the Ministry of National Resources with its State Secretariat for Healthcare; see section 2.3.3). Subsequently, the National Assembly decides on the submitted proposals.

The second component is a target subsidy (that is, a matching grant), which allows local governments less discretion because both its purpose and conditions are predetermined by the National Assembly (1992/9). In the health sector, local governments can apply for target subsidies to purchase medical equipment, such as X-ray machines or dental equipment. The local share required varies each year: for example, for the 2011–2012 period, local governments can apply for a matching grant of over HUF 1 million (€3630) to purchase anaesthesiology and intensive therapy equipment, with a minimum local share of 25% (2009/7).

The third component of the system used to be a budget that had been devolved to the county councils for regional development, which decided on the allocation of funds among various applicants. Target-type decentralized grants (céljellegű decentralizált támogatás, or CÉDE) were introduced in 1997 (1997/13), but were eliminated in 2006 when EU funding became the main source of capital grants in the health sector (2006/9).

For the 2007–2013 budget period of the EU, Hungary is the recipient of €22.4 billion from the various structural and cohesion funds, out of which the government decided to spend €1.8 billion on various health care infrastructure development projects, including the renovation of hospitals, polyclinics and primary care surgeries, and on the building of new polyclinics and health centres in primary care (2006/4). In preparation for the grant agreement between Hungary and the EU, major changes were implemented in the existing capital financing system. Not only was the decentralized component (that is, the CÉDE) of the earmarked and target subsidy system eliminated in 2006, but the National Assembly also suspended new conditional capital grants and authorized the government to harmonize actual investment decisions and ongoing projects with upcoming EU funding (2006/11). Since 2008 the scope of matching grants has been limited to a specific health care purpose (2007/10). There is no doubt that EU funds have become almost the only source of capital investment, although local governments must still make efforts to provide the required local share. Providers often have to contribute from their own resources (for example, income from paying services or donations to hospitals founded by charities). It is worth noting that private providers are also eligible for the various public grants if they supply services to the population of a local government under the territorial supply obligation.

Other important capital financing options are the various capital grant programmes run by the Ministry of National Resources/State Secretariat for Healthcare to replace medical equipment or to support providers in meeting minimum standards. These programmes also shrank during the phasing in of EU funds. For the most part, the health sector did not participate in the large-scale public–private partnership (PPP) investment programmes initiated by the government in power from 2002 to 2006. The only health care related examples are two higher education PPP projects at Semmelweis University, Budapest.

Table4.3 shows the distribution of EU structural and cohesion funds in the health sector up to April 2011. Of the total funding awarded, almost three-quarters has been allocated to the inpatient care sector, less than 5% to primary care and less than 1% to health promotion. On the other hand, special emphasis has been placed on the development of medical rehabilitation, emergency care and blood supply and on the development of disadvantaged subregions, for which a disproportionately large number of projects and the corresponding funds have been approved. There are also 22 cross-border collaborative development projects under implementation with five neighbouring countries, and further projects have been planned with Croatia and Serbia (Ministry of National Resources, 2011).

Table4.3

Given that capital investment in health care has been chronically underfunded in Hungary, the influx of EU funds has been indispensable. Between 1994 and 1999, public investment in health care was almost halved in real terms and, as a share of GDP, decreased from 0.46% to 0.39% between 1996 and 2003 (State Audit Office, 2005). The central government has always been in a position to control its expenditure and investments through the system of earmarked and target subsidies, despite the dominance of local governments in the ownership of health care providers. Between 1991 and 2004, local governments received HUF 184 billion (€697 million) in earmarked subsidies, mainly for the renovation of existing inpatient care facilities, but the total amount of capital grants showed a decreasing trend in real terms between 1996 and 2003. According to the findings of the State Audit Office of Hungary, funding for capital costs has been unstable, has not been related to the health care needs of the population and has not been based on an approved health sector development plan (State Audit Office, 2005).

4.1.2. Infrastructure

In 2009, local governments owned 78% of all hospital beds in Hungary, almost 20% of which (15.2% of all beds) were in Budapest. Of the total number of approved beds, university clinical departments had 9.7%, the National Institutes of Health had 5.9% and health care institutions of other ministries had 2.5%. In addition, 3.8% of all hospital beds were owned by churches and charities operating hospitals with a territorial supply obligation and therefore eligible for HIF financing (HCSO, 2010f). Private non-profit-making organizations operate in several fields of inpatient care, the majority of beds being provided for internal medicine, paediatrics, psychiatry and follow-up care (NHIFA, 2010).

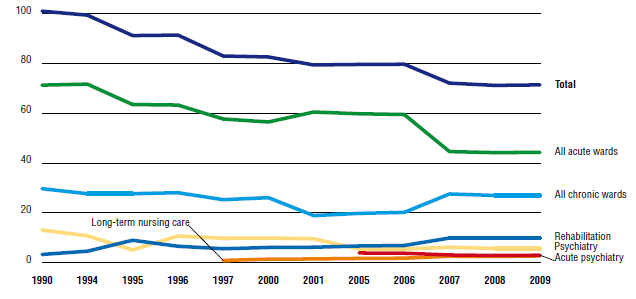

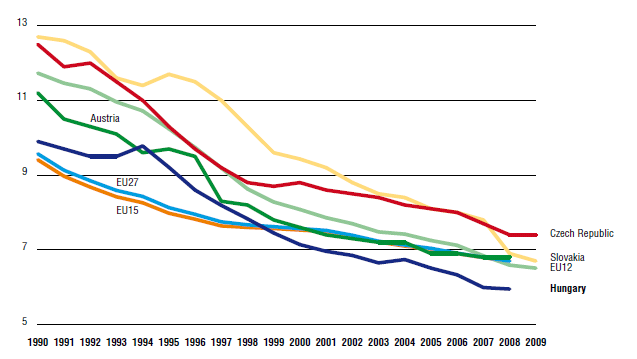

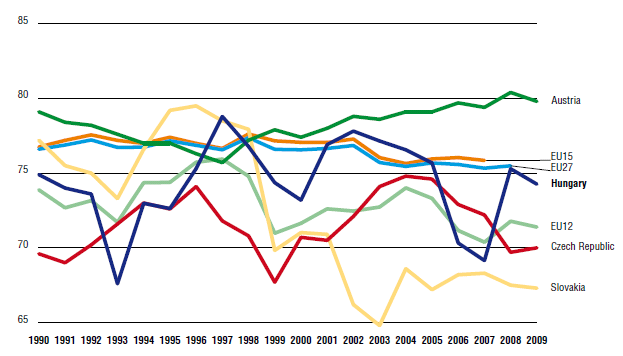

Over the past 15 years, Hungary has followed the general European trend of reducing the number of acute hospital beds both through real reductions and bed reallocations to different types of services (Fig4.1). There were two major waves of bed reductions – the first between 1995 and 2001 and the second in 2007 – as part of fiscal stabilization packages prompted by very high deficits. In general, the average length of stay (Fig4.2) and hospital admissions rates have also decreased since 1990, as have occupancy rates (Fig4.3). For more information on trends in the mix of beds in the Hungarian health care system see sections 5.4, 7.3.2 and 7.5.2.

| Fig 4.1 | Fig 4.2 | Fig 4.3 |

|  |  |

One of the main legacies of the Semashko-style system in place during the communist era was an oversized hospital sector, which came to be considered inefficient and inequitable (see section 7.5.2), leading to calls for restructuring and downsizing. In the first phase of reforms in the mid-1990s, the government introduced a DRG-based hospital payment system for acute inpatient care and per diem payments for chronic inpatient care, as well as a three-member structure for top hospital management, according to which a financial director, medical director and nursing director managed the institution together. These measures did not produce significant structural reorganization in the hospital system, but it has to be noted that a uniform base rate was not introduced until 1998 (1996/14).

The next government attempted to address the issue more directly. First, as part of the restrictive package of 1995, the Ministry of Welfare[15] became responsible for bed reduction decisions by determining the capacities to be contracted for under the territorial supply obligation by local governments. A total of 8000 beds was removed from the system in 1995 (1995/5), but the decision-making process was found to be unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court (1995/13), which ordered the government to develop a more systematic method for applying the territorial supply obligation. The 1996 Capacity Act determined the maximum number of beds and outpatient consultation hours per specialty and per county based on a formula that aimed at representing the health needs of local populations (1996/4). The Act was expected not only to reduce the number of beds considerably but also to produce a more equitable geographical distribution. Its implementation was left to the county consensus committees summoned by the NPHMOS and comprising representatives of local health care providers such as hospitals, the local branches of the Hungarian Medical Chamber and county offices of the NHIFA (see section 2.2). In counties where beds had to be reduced based on the formula, the county consensus committees had to agree which provider would give up how many beds. As a result, the number of beds decreased by another 9000 in 1997, and remained at around 80 beds per 10 000 population until 2006. The government also endorsed cost-effective forms of care, including same-day surgery and home care. For instance, in 1996, a separate HIF sub-budget was created for home care services, for which HIF expenditure was also increased (see also section 5.8).

As a result of all these changes, the number of acute hospital beds was reduced by 20% between 1992 and 1997 and the number of hospital beds for chronically ill patients was also reduced by 17%, according to national statistics. The next major wave of downsizing in acute inpatient care capacities took place in 2007 (2006/12). More than 25% of acute beds were removed from the system, with a parallel increase in the number of chronic beds. Six hospitals were closed, twelve remained without acute beds, and one or more acute wards were closed in thirty-three other hospitals.

The number of acute hospital beds per 1000 population in Hungary ranked above the EU15 and EU27 averages in 2008, but below numbers for neighbouring countries with similar economic development, such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Fig4.4). Capacities for long-term nursing care in both the inpatient and outpatient setting are still considered insufficient and thus unable to meet the needs of the ageing population(see also section 5.8).

Fig4.4

- 15. As of 2010 called the State Secretariat for Healthcare within the Ministry of National Resources. ↰

4.1.3. Medical equipment, devices and aids

The operation and licensing of medical equipment (including medical aids and prostheses) is run by the Authority for Medical Devices of the State Secretariat for Healthcare (2000/4). The Authority replaced the Institute of Hospital and Medical Engineering, which was renamed and continues as an organization of quality control and audit in this area (1990/2). The registration and licensing system was harmonized with the practice of the EU (1999/7), along with that for pharmaceuticals.

Minimum standards for health care institutions (regarding personnel, equipment and buildings) were introduced as a rationalization measure in 1996 and 1997. Buying new and replacing obsolete equipment falls to the owners of facilities, who can either pay from their own sources or apply for a conditional or matching grant. Various capital grant programmes are run by the Ministry of National Resources for replacing medical equipment or supporting providers in meeting minimum standards. EU capital grants have also played an increasing role in the funding of medical equipment in recent years (see also section 4.1.1 above). In 2008, there were 28 magentic resonance imaging (MRI) units, 71 CT scanners and 6 PET units functioning in hospitals and ambulatory units (European Commission, 2011).

4.1.4. IT

In 2010 the rate of regular internet users in Hungary was 61%, only slightly below the EU27 average (65%). It has increased almost by 200% since 2004 (21%). At the same time, the share of individuals using the internet to seek information with the purpose of learning was 31%, only 1% lower than the EU27 average (European Commission, 2011). The recent government action plan states that a broadband connection is available for 97% of the population but only 19.7% use it, and that 55% of the population own a personal computer. There are 11 million mobile phone subscriptions, which is about 10% more than the size of the population (Ministry of National Development, 2010).

The use of IT in the health sector has developed gradually. It is largely attributable to the introduction of new payment techniques in 1993 and subsequent important requirements for financial administration and reporting, such as ad hoc provider checks of patients’ health insurance status and eligibility for services since 2007. The development of IT in the health care context was supported by a strategic vision of the Ministry of Health, Family and Social Affairs in 2003, which was based on a recommendation of the Ministry of Telecommunications (Ministry of Health, Family and Social Affairs, 2003). The implementation of the strategy, which aimed primarily at increasing the number of informed individuals and communities, was found to be only moderately effective (WHO, 2006). Nevertheless, one of its successful initiatives was the establishment of a web- and telephone-based health information centre available around the clock, which offers quality information not only to citizens but also to providers. The current government IT strategy, now coordinated by the Ministry of National Development, aims to improve IT capacities in the health system. Some of the initiatives of the 2003 plan – such as the establishment of electronic prescribing and medical records, and the creation of systematic mechanisms to keep registration databases updated and transparent – were not implemented. The new action plan will put them into practice, along with other initiatives that include, for instance, the horizontal integration of provider IT systems in order to increase interoperability and to reinforce patient data transfer between providers, starting in the second quarter of 2011 (Ministry of National Development, 2010).

Regarding the current level of IT use in primary care, a study of the European Commission based on 2007 survey data ranked Hungarian family doctors as solid average performers among EU countries with regard to eHealth utilization. They ranked ahead of all central and eastern European countries except Estonia. Almost all family doctors in Hungary regularly used IT to store administrative and medical files, but effective IT solutions (for example, for transferring lab results or for electronic prescriptions) are not in use due to a lack of technical prerequisites. Only 35.7% of primary care physicians in Hungary had broadband internet access in 2007, which was well below the European average (47.9%). They used their computers for consultation purposes (84%) and to access decision support systems (93%), but were reluctant to develop practice web sites. Indeed, only 9% of primary care physicians in Hungary had a web site for their practice in 2007, which was one of the lowest rates in the EU (European Commission & Empirica, 2008).

New rules related to the digital appointment booking system of the Hungarian National eHealth Infrastructure (EESZT) require outpatient providers (who use the booking system) to offer all available appointments for non-urgent care in the booking system. Exceptions include appointments reserved for in-house referring physicians, check-ups and special care procedures performed only by certain providers.

Not all outpatient providers currently use the digital appointment booking system, though the number is growing [1]. The new rules offer financial incentives for outpatient providers offering specified imaging procedures, allowing an increase in their planned annual budget if they use the booking system.

The rules, published in March 2025, aim to enhance the efficiency of the digital appointment booking system [2]. Although the Hungarian healthcare system follows the principle of territorial supply obligation, the new rules allow patients and physicians to book outpatient appointments with providers outside their assigned area.