-

23 June 2025 | Country Update

Tallinn Hospital Group to consolidate city-owned healthcare providers

4.1. Physical resources

The Tallinn City Council has proposed the establishment of a joint-stock company, Tallinna Haigla (Hospital of Tallinn), to consolidate city-owned healthcare institutions into a single corporate group. This includes East Tallinn and West Tallinn Central Hospitals, the Children’s Hospital, the Dental Clinic and the Tallinn Ambulance Service. The objective is to improve operational efficiency and reduce duplication. The new company will also incorporate the Tallinn Hospital Development Foundation, the entity originally established to lead preparations for the creation of Tallinna Haigla, and will take over its functions.

In the first phase, a holding structure will be created, with legal mergers of the entities planned at a later stage (no exact timeline suggested). The new parent company will coordinate strategic operations and oversee the development of a new medical campus. Until the legal mergers are completed, providers within the group will continue to operate autonomously and remain individually contracted by the Estonian Health Insurance Fund.

This development is in line with Estonia’s Hospital Development Plan 2040, which envisions the eventual consolidation of the city’s two central hospitals and the children’s hospital with the state-owned North Estonian Medical Centre. However, this current step applies only to facilities owned by the Tallinn City Government, as there is no political consensus to proceed with a larger scale merger.

Authors

References

4.1.1. Infrastructure, capital stock and investments

Infrastructure and capital stock

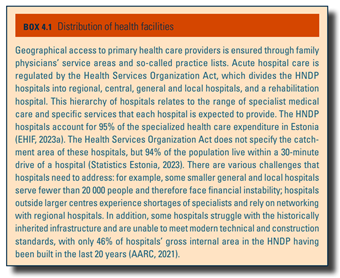

In 2021, there were more than 1483 health care institutions in Estonia. Among the PHC providers, two PHC providers were in public ownership and the remaining 421 facilities were privately organized. Inpatient acute care providers included 20 public hospitals that are part of the HNDP, 11 public hospitals that are not included in the HNDP and 19 private hospitals. Inpatient nursing care providers (which provide long-term care for patients requiring medical/nursing care) constitute 11 private hospitals and nine public hospitals, which are not part of the HNDP (NIHD, 2023b). The rest of the providers are dental care, ambulance, outpatient specialist care, rehabilitation or outpatient nursing care providers and diagnostic centres, the majority of which are privately owned. The Health Services Organization Act regulates the geographical distribution of health care facilities (see Box4.1).

Box4.1

Since 2009, the MoSA has been steering the development of PHC infrastructure, investing EU structural funds in refurbishment of existing PHC facilities and the building of new ones (Ministry of Social Affairs, 2014). The goal of this investment was to improve the infrastructure and expand the scope of services provided by multidisciplinary PHC teams, which would be better equipped to deal with the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases than individual family physicians (Habicht, Kasekamp & Webb, 2022). The Estonian Health Care Development Directions until 2020 describes the desired structure of PHC providers. According to this plan, PHC centres should include at least three or four family physicians, three or four family nurses, a midwife, a physiotherapist, and a home-care nurse. Their activities should cover a population of 5000 to 6000 patients (see section 5.3 Primary care). The MoSA identified locations for PHC centres based on projections of population change and service needs, and also specified positions for affiliated PHC centres in smaller rural areas. Where possible, established PHC centres or their branches were incentivized to share infrastructure with nursing hospitals, ambulances or specialist care providers.

In 1991, Estonia had about 120 hospitals in total, and by 2021, 50 remained. Most small hospitals were closed, merged or turned into nursing homes. In 2003, adoption of the HNDP was aimed at restructuring the extensive network of public hospitals. The HNDP includes 20 publicly owned acute care hospitals and one rehabilitation hospital. HNDP hospitals vary in size and profile. Up until now, the HNDP remains in place and serves as a main tool in hospital planning (Government of the Republic of Estonia, 2003). The aforementioned 19 private hospitals are for-profit and focus on provision of selected specialized services (nursing care, gynaecology, orthopaedics, psychiatry) (NIHD, 2023b) (see section 5.4 Specialized care).

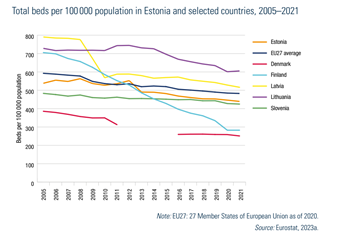

The total number of hospital beds decreased from almost 538 beds per 100 000 population in 2005 to 439 beds per 100 000 in 2021, which is lower than the EU average of 483 beds per 100 000 (see Fig4.1).

Fig4.1

Tartu University Hospital and North Estonia Medical Centre (in Tallinn) are the two largest hospitals in Estonia, which are also regional hospitals and focus on providing a wide range of secondary and tertiary health care services (see Box4.1). Since 2014, the state has promoted the networking of the regional level hospitals with general hospitals with the aim of enhancing access to specialized care in smaller hospitals by sharing available resources (health professionals, technologies) in a coordinated way (see section 2.7.2 Regulation and governance of providers). By 2018, the two regional hospitals had coordinated a network of six general hospitals. Although the network was expected to expand further, there have been no changes since 2018. In addition, there are other collaboration agreements between central and general hospitals, for example for specific treatments such as cancer.

Regulation of capital investment

Health care institutions in Estonia are financially independent. Since 2003, the capital costs have been calculated into the price list of services reimbursed by the EHIF to cover the investment in medical technology and depreciation of premises. Therefore, the capital costs are not allocated according to investment needs, but rather on the basis of activities, that is, services provided (Tsolova et al., 2007). For PHC facilities, payments from the EHIF should cover capital costs. In addition, some municipalities support local facilities with preferential rents, free premises or extra funding (see section 3.6 Other financing).

In the hospital sector, the HNDP is the main instrument for planning and realizing capital investments. The needs described in the HNDP have served as a basis for the implementation of the EU structural funds, which have become an additional source of investment in the health care system since 2004 (see section 3.6.2 External sources of funds).

In addition, the state can steer public investment by approving the functional development plans of hospitals and the medical technology parts of construction projects through mandatory regulation. Functional development plans cover analysis of local health needs, service provision volumes and functional plans for service provision.

Investment funding

The Estonian Government, in alignment with the European Commission, decides on the use of EU structural funds, their distribution and the balance between investments in different levels of care. The first two rounds of EU investment in infrastructure concentrated on renovation and expansion of the facilities for tertiary and nursing care. The third period (2014–2020, €132 million) is currently investing €106 million in 55 PHC centres. It also covers the modernization of a general hospital and software development for all PHC facilities. The majority of the EU’s investment requires cost sharing from the providers. There have been cases where providers were unable to negotiate private loans to build or refurbish facilities (see section 3.6.2 External sources of funds).

In 2020, the MoSA initiated the Person-Centred Integrated Hospital Master Plan 2040 project with funding from the EU Technical Support Instrument. The aim was to analyse the organization of Estonian specialist medical care and the hospital network and to propose a new hospital network plan for the year 2040 (AARC, 2021). The report proposes to further strengthen the coordinating role of PHC providers in health maintenance, disease prevention and chronic disease management. It suggested that hospitals serving fewer than 20 000 people should be transformed into community hospitals, providing services to patients with sub-acute episodes of chronic disease. The community hospital system would become part of the PHC network (see section 2.4 Planning). By 2023, no political decision had been made on the next steps towards the 2040 plan.

Some hospitals in Estonia are still large complexes spread over several locations, which do not meet population needs and are too expensive to operate. This is, for example, the case in Tallinn, where two central hospitals are seeking to overcome these challenges by merging and reopening in a newly built facility. The initiative is supported by the city, but the financial backing required is missing from the national government. By 2022, the merger plans had been finalized and the EU had agreed to fund the construction of the Tallinn hospital from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility. However, in the summer of 2022, amidst changes in government composition, the government removed health care investments for the new Tallinn hospital from the list due to increased prices and concerns regarding the project execution timeline (Ministry of Social Affairs, 2022d) (see section 3.6.2 External sources of funds).

As seen above, EU funds play an important role in funding capital investment in the Estonian health system. In the absence of these funds, the current system does not provide sufficient incentives for individual health care providers to initiate capital investments. In addition, these investments have been strategically used to incentivize reform within the system. Therefore, a plan is needed for sustaining health care infrastructure investment and aligning this with changes in health service delivery and population needs.

4.1.2. Medical equipment

Health care institutions, including acute and nursing care hospitals, and those providing PHC or specialist outpatient medical services, are independent in their decisions on the introduction of new medical technologies and must fully finance their acquisition. HNDP hospitals must include new medical technologies in their functional development plans, which are approved by the MoSA. A regulation specifies only the minimum equipment required for different types of hospitals and PHC facilities. Providers use various short-term and long-term loan schemes to buy, rent or lease medical equipment. Nonetheless, there is no guarantee that the costs will be covered by EHIF contracts, which may limit providers’ ability to purchase new technology.

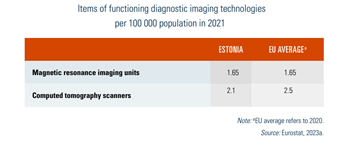

In 2021, there were 2.1 computed tomography (CT) scanners per 100 000 population and 1.65 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units per 100 000, both of which are nearing the EU average (2.5 per 100 000 and 1.65 per 100 000, respectively; see Table4.1). The vast majority of CT scanners (89%) and MRI units (77%) were available in hospitals (NIHD, 2023b). Estonia is about average in the EU in terms of major diagnostic imaging and radiotherapy equipment, but 20% of CT scanners and 44% of MRI units were more than 10 years old (AARC, 2021). Estonia performed an average of 5584 MRI scans per 100 000 inhabitants in 2021, whereas the EU average was 6699 per 100 000 (albeit for 2020) (Eurostat, 2023a). The trend in MRI use has been increasing (NIHD, 2023b).

Table4.1

PHC providers have basic medical equipment, such as electrocardiograms, minor surgery equipment, as required by the regulations. Some practices also use ultrasound equipment and clinical blood analysers. For other diagnostic tests and treatments, the PHC provider purchases the services from other providers, hospitals or private diagnostic centres (see section 5.3 Primary care).

4.1.3. Information technology and e-health

Estonia has been at the forefront of digitizing all citizens’ interactions with the state. The backbone of the national digital information system is X-Road, which is a data exchange system that allows different information systems to be linked, enabling the operation of various e-services in both the public and private sectors. All providers must have information technology systems in place as electronic data transmission is compulsory in Estonia.

In 2005, the MoSA initiated the development of four major e-health projects – the ENHIS, which mainly includes electronic health record, digital images, e-booking system and digital prescription (see section 2.6 Health information systems).

The ENHIS links the existing information systems of all health care providers and contains comprehensive data on a patient’s interactions with the health system – his or her medical records, data on visits to all health care providers and other health-related information. Providers are required to submit relevant medical information to the ENHIS. The decentralized approach to e-health solutions, where providers have their own information systems and send data to the ENHIS, has proved to be challenging in terms of ensuring compatibility and interoperability. The vast majority of data collected by hospitals are not collected in a standardized or structured way. Patient clinical data are primarily captured in the free-text form, and the quality of clinical data is generally low (AARC, 2021). Furthermore, the information in ENHIS becomes available to the patient and other stakeholders after the case is closed. This substantially limits real-time use of data for clinical decision-making in an ongoing episode of care. These challenges were at the heart of the UpTIS project, which the MoSA launched in 2021 with EU funding to improve the current ENHIS and address the digital needs of stakeholders. (Ministry of Social Affairs, 2022f )

Individuals can access their own full medical records through the national patient portal. In addition to individual health data, patients can see the cost of each service covered by the EHIF. Patients can also dispute medical claims submitted by providers through the patient portal. The results of the 2021 patient survey indicated that 90% of the population is aware of the patient portal and 76% have accessed it at least once. The main use of the portal is to check one’s own health data, but an increasing number of people use the ENHIS to book medical appointments (Kantar EMOR, 2022) (see section 2.8 Person-centred care).

The Estonian Picture Archiving and Communication System manages another e-health platform – the Digital Image Archive. This allows health care providers to access patient’s digital images to monitor longitudinal changes in a patient’s health. Since 2014, all health care providers have been required to share digital images via the platform, which are then linked to ENHIS records.

In 2019, the National e-booking system was finalized. Thanks to this, individuals are able to book, cancel and reschedule appointments for outpatient specialist care visits with those providers who are part of the central platform. The medical institutions have to provide the details of all bookings and completed visits to the ENHIS and link them to a referral, if one is available. Patients can also view valid and unused digital referral letters in the ENHIS and schedule an appointment based on them. The National e-booking system enables the EHIF and TEHIK to monitor access to specialist visits and therefore assess the waiting times (see section 3.3.4 Purchasing and purchaser–provider relations).

Estonia has had a national e-prescription system since 2010. Doctors fill out prescriptions using their own computer software, which are then transferred to a national database managed by the EHIF. The e-prescription becomes immediately accessible in any pharmacy at the patient’s request. Moreover, patients can review their medication history via the patient portal or the state portal (www.eesti.ee – Riigiportaal, 2023). Physicians are also able to access this information electronically, which helps them to improve patients’ pharmaceutical plans and prevent harmful polypharmacy. A comprehensive database of drug interactions has also been introduced in Estonia to limit the risk of inappropriate prescribing.

The EHIF medical claims database serves as the main source of data for the analysis of health care utilization, as it provides reimbursement data on the use of health care services. This database is limited to the services purchased by the EHIF and does not include services outside the benefit basket or services delivered by providers without a contract with the EHIF.

Apart from the major e-health projects described above, there are numerous initiatives in the development or implementation phase. Some of these were accelerated in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, during the pandemic, users could register for COVID-19 test or vaccination and access the results and immunization certificates through the patient portal. Furthermore, the EHIF started to fund remote visits by specialists and promoted telemedicine consultations. Following this trend, two private online clinics have opened, focusing exclusively on providing teleconsultation services to the patients.

Among the challenges facing the Estonian e-health ecosystem are unharmonized regulations and low levels of interoperability. Currently, different stakeholders independently develop their own terminologies and data structures, which increases the burden of software development or leads to manual data processing (AARC, 2021).