-

23 June 2025 | Country Update

Council for Efficiency and Economic Growth established to advise prime minister on deregulation and bureaucracy reduction -

05 March 2025 | Country Update

A new health technology assessment guideline in Estonia

2.7. Regulation

Article 28 of the Constitution of the Estonian Republic states the people’s right to health protection and social security. The regulatory framework of the Estonian health system is laid down in such main pieces of legislation as the Health Insurance Act (2002), the Health Insurance Fund Act (2000), the Health Services Organization Act (2001), the Public Health Act (1995), the Medicinal Products Act (2005) and the Communicable Diseases Prevention and Control Act (2003).

At the state level, the MoSA is responsible for the regulation and stewardship of the health system. Some regulatory functions (such as state financial and strategic planning) are carried out by other ministries. The health acts are enforced through governmental and ministerial regulations and by authorities with a state supervision role such as the Health Board.

The state and local municipalities exert influence on the regulatory and planning processes of hospitals through participation in supervisory boards. Patients are represented in working groups and commissions of the MoSA, and are also members of the Supervisory Board of the EHIF. In general, the governance of the health system is based on regulation and contractual relations rather than on subordination.

The Council for Efficiency and Economic Growth has been established to provide the prime minister with concrete proposals for deregulation, reducing administrative burdens and advancing measures to support economic growth. The council is composed of entrepreneurs from a range of sectors. Its core objectives are to identify regulations and reporting obligations that entrepreneurs consider excessive, to lower compliance costs, and to propose improvements to administrative processes that could facilitate growth. While decisions on how to use the resulting workload reductions and cost savings rest with the public sector, the council does not deal with staffing cuts or institutional downsizing.

The council will operate from March 2025 to September 2026, holding monthly meetings and convening thematic working groups as needed. Instead of producing a comprehensive report, proposals are discussed promptly in the government’s economic cabinet meetings and published every six months. All proposals are publicly available (see references). As of mid-June 2025, 548 unique proposals have been submitted, including 21 addressed to the Minister of Social Affairs. These cover a wide range of topics, for example discontinuing the development of the Alcohol Consumption Reduction Strategy 2025–2035 that is a follow-up strategy to the Alcohol Policy Green Paper (see the policy analysis “Estonian alcohol policy evaluation and policy considerations” https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/monitors/health-systems-monitor/analyses/hspm/hspm-estonia-2023/estonian-alcohol-policy-evaluation-and-policy-considerations) or exempting temporary employees (“summer workers”) in food service establishments from the health certificate requirement. The council is supported by the Government Office and relevant ministries.

Authors

References

2.7.1. Regulation and governance of third-party payers

The Estonian Health Insurance Fund Act of 2000 established the EHIF as the only legally independent public organization responsible for payment and purchase of health services. The EHIF has broad autonomy to contract service providers while maintaining government supervision and participation. Important policy decisions about the health insurance system remain with the parliament, the government or the MoSA (see section 2.2.1 The role of the state and its agencies).

2.7.2. Regulation and governance of providers

The Health Services Organization Act came into force in 2002. It established a separate state agency, the Health Care Board (now the Health Board), for the licensing and supervision of providers. The Act clearly defines all providers as entities operating under private law, with the public interest being represented through membership of supervisory boards for publicly owned providers (state, municipalities). Family practices can be organized as joint-stock companies or as private enterprises, owned by family physician(s) or local municipalities (see section 5.3 Primary care). Hospital providers are allowed to organize themselves as joint-stock companies (for-profit) or foundations (not-for-profit). Ambulance services, pharmacies, nursing care and public health providers may take a different legal form.

Statutory mechanisms to ensure minimum standards of provider competence include:

- Health Board licences for (public and/or private) health care facilities and all health service providers (family physician practices since 2013);

- Health Board registration of doctors, dentists, nurses and allied practitioners (for example, midwives), pharmacists and assistant pharmacists, supporting medical experts like physiotherapists, speech therapists and clinical psychologists (see section 4.2.1 Planning and registration of human resources);

- SAM approval for medicines sold and used in Estonia and licences for pharmacies;

- notification to the Health Board for new devices on the market and also for hazards that may occur after market entry;

- safety certificates issued by the Health Board or other national competent authorities for medical devices or health-related equipment;

- the Estonian Data Protection Inspectorate approval for concordance of processing of the health-related personal data by health care providers or registries; and

- voluntary external quality assessments and improvement programmes in line with statutory inspection requirements.

Furthermore, the Health Services Organization Act formalized the requirements for health service providers to assure quality. It requires all providers to develop an internal quality assurance system that includes conducting clinical audits, establishing internal guidelines for managing critical areas and ensuring patient satisfaction. The NHP provides the framework for patient safety and quality assurance in Estonia. However, the requirement for health care providers to have liability insurance and to establish an adverse events database was first adopted in 2022 (see section 2.8.3 Patient rights).

The EHIF coordinates the development of evidence-based systematic guidelines using the Estonian Handbook for Guidelines Development, updated in 2020 (EHIF, 2021a). The process is governed by the Guideline Advisory Board, with 12 members including nurse and patient representatives, and is methodologically supported by the University of Tartu since 2018. By early 2022, 32 national guidelines on diverse topics, complemented by relevant patient materials, have been approved (Tartu University & EHIF, 2023).

In 2013, the Advisory Board for the Development of Quality Indicators was established in cooperation with the University of Tartu and the EHIF. The board members are clinicians who have taken a leading role in the development of quality monitoring indicators. The reports on quality indicators for neurology, oncology, intensive care, gynaecology, surgery and psychiatry have been published since 2017. Additionally, the reports present surveillance indicators for clinical guidelines and feedback indicators for health providers.

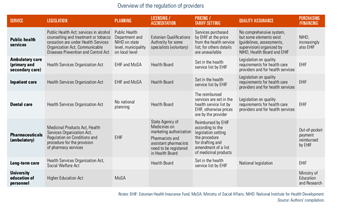

Table2.1 provides an overview of the regulation of providers.

Table2.1

2.7.3. Regulation of services and goods

Benefit package

The benefit package in Estonia consists of lists for health services, medicines and medical devices covered by the EHIF. Regulations on the inclusion of goods and services in the statutory benefit package have been in effect since 2002. In 2018, the responsibility for the list of pharmaceuticals was transferred from the MoSA to the EHIF (see section 3.3.1 Coverage).

The list of health care services is amended at least once a year, based on the needs and financial possibilities of the health insurance fund, taking into account the medical efficacy, cost-effectiveness and budgetary impact of the proposed service, as well as societal needs and alignment with the health policy objectives. Since 2018, the committee for health service list and hospital care committee have been advising the EHIF on updating the list, the application criteria for health care services and the reference price. The committee’s 13 members include representatives from the EHIF, MoSA, professional and patient organizations and others.

The list of reimbursed outpatient medicines is updated quarterly. The criteria for the inclusion of medicinal products are listed in the Health Insurance Act and are: the need for the medicine, proven medical efficacy, economic rationale, availability of alternative medicines or treatments, and affordability. The procedure for drawing up and amending the list of medicines of the EHIF is laid down in a ministerial regulation. Only manufacturers may submit applications for new active substances, but other interested parties may also hand in applications for amendments. These applications are thoroughly evaluated by the EHIF and the SAM, and discussed by the Medicines Committee, which consists of eight members representing professional and patient associations, the University of Tartu, the SAM and the MoSA (see section 3.3.1 Coverage).

Health technology assessment

The Centre for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) was established in 2012 under the Institute of Family Medicine and Public Health at the University of Tartu, with a staff of eight to 10 researchers. It also has an expert committee comprising the experts from health authorities, professional societies and academia. By 2022, the centre had produced 58 HTA reports. Since 2019, the EHIF has financed HTA activities commissioned in the Centre at the University of Tartu. Several stakeholders can make suggestions for topics, but the HTA board decides on the topics for HTA. The recommendations and conclusions of the reports assist in decision-making on the inclusion of new technologies in the benefit package, the adjustment of clinical guidelines and advice on the economic use of resources. In summary, considerable progress has been made in Estonia in establishing formal procedures for HTA and developing capacity in this field to support evidence-based decision-making in health care and public health.

In early 2025, Estonia introduced a new health technology assessment (HTA) guideline, replacing the 2002 Baltic Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation of Medicines [1]. Developed by a multistakeholder group (including experts from the Estonian Center for HTA, Estonian Health Insurance Fund (EHIF), Association of the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers in Estonia, Estonian Chamber of People with disabilities, Ministry of Social Affairs and its Department of Medicines), this revision aims to modernize the evaluation process for medicines, health services and medical devices, and to ensure that the EHIF coverage decisions are based on robust evidence.

The new guideline defines the stages of the HTA process, the principles for stakeholder involvement, and the evaluation methodology, including how evidence and cost-effectiveness are assessed and the criteria for decision-making [2]. The guideline serves as a foundation for:

- Clinical and economic assessment of health technologies

- Submitting and evaluating applications for the inclusion of health services, medicines and medical devices in the benefits package

- Determining reasonable prices for health technologies in Estonia

The target audience includes organizations submitting applications for EHIF-covered benefits and committees reviewing these applications (for example, the Pharmaceuticals Committee, Hospital Medicines Committee and Health Services List Committee).

Authors

2.7.4. Regulation and governance of pharmaceuticals

The pharmaceutical sector in Estonia was reformed in the early 1990s with the aim of establishing pharmaceutical regulatory authorities, creating a legislative framework, introducing a system of reimbursement for pharmaceuticals and privatizing pharmaceutical services. The Medicinal Products Act, originally adapted in 1995, covers all medicinal products and pharmaceutical activities in Estonia. In 2002, the Medicines Department was established within the MoSA, which has been in charge of the strategic planning of pharmaceuticals, except for vaccines, pricing and reimbursement decisions. Since 2018, the EHIF has taken over responsibility for administering the positive list and pricing, as well as central procurement of selected medicines and vaccines. The main regulation for vaccine planning is the Immunization Schedule, which is based on the Communicable Diseases Prevention and Control Act and is issued by the MoSA, which is advised by an Expert Committee on Immunoprophylaxis on implementing, updating and supplementing the schedule.

The Estonian pharmaceutical regulatory framework is harmonized with EU legislation and international guidelines and is based on proven quality, safety and efficacy. Since Estonia joined the EU in 2004, the SAM has been an active member of the EU medicines regulatory network. The SAM is in charge of supervision of pharmaceutical advertising. Advertising of prescription medicines and academic details is restricted to physicians and pharmacists, and there are detailed rules on what promotional activities are acceptable. In line with EU law, advertising to the public is only allowed for over-the-counter (OTC) medicines, with strict directions on what information must be presented and how (see section 5.6 Pharmaceutical care).

Patent legislation in Estonia is harmonized with the European Patent Convention and ensures market protection to the originator of a medicinal product for 20 years. EU Supplementary Protection Certificates oblige the authorities to provide additional data protection for patented pharmaceuticals for a 10-year period. After eight years, the SAM can start processing applications for generic medicines under the European Commission Bolar Amendment, which can then be marketed immediately after the 10-year data protection period ends. To date, there are no explicit provisions in the national legislation regarding parallel import and government use of patented products.

Since 1993, there has been a reimbursement system for prescription-only medicines purchased from pharmacies. The reimbursement category (100%, 90%, 75% or 50% rate) determines the level of patient co-payment and is based on the severity of the disease, the efficacy of the medication and the social status of the patient by the regulations of the MoSA (see section 3.4.1 Cost sharing (user charges)). In 2002, the EHIF introduced a positive list of fully reimbursed pharmaceuticals. In addition, patients have the option of applying to the EHIF for individual reimbursement in special circumstances. This is mainly used for pharmaceuticals without a valid marketing authorization in Estonia.

Since 2002, manufacturers’ applications for EHIF reimbursement have followed the common Baltic guidelines for pharmacoeconomic analysis. The application to the EHIF must be accompanied by clinical and pharmacoeconomic data. The SAM then evaluates the clinical data, while the EHIF assesses the economic data. Both provide a written report to the Medicines Committee, which makes recommendations for price setting. In case of a positive opinion, the EHIF and the manufacturer negotiate the price. The difference between the retail price and the reference price has to be paid by the patient. Manufacturers are free to set their own prices for non-reimbursed pharmaceuticals.

There are no profit controls or any clawback systems to recollect excess profits on pharmaceutical sales. The only administrative measure used is the cost plus mark-up system for wholesalers and pharmacies, which sets the maximum mark-ups for both reimbursed and non-reimbursed medicines, including OTC drugs. This method regressively differentiates the mark-ups for pharmaceuticals, thus aiming to make the sale of cheaper medicines more profitable for pharmacies (Pudersell et al., 2007) (see section 5.6.3 Cost-containment measures applied to pharmaceuticals).

Pharmaceuticals used in hospitals are usually included in the price of health services paid by the EHIF. However, some selected groups of pharmaceuticals (cancer chemotherapy, dialysis products) are included in the list of health care services as separate units of pharmaceutical care and are paid for by the EHIF in addition to health services.

There are no pharmaceutical budgets for doctors or mandatory generic substitution in pharmacies in Estonia. However, the regulations require doctors to prescribe pharmaceuticals by their International Nonproprietary Name. When prescribing by brand name, the doctor must justify this in the patient’s medical record (for example, the patient refuses generic, or the cheapest option is not available). If the pharmaceutical has been prescribed by International Nonproprietary Name, the pharmacist or assistant pharmacist has to offer different generic equivalents to the patient and advise on the prices accordingly.

Since 1 April 2020, after a five-year transition period, pharmacies can only be owned by pharmacists, so 469 pharmacies (498 at the beginning of the year) continued to operate (State Agency of Medicines, 2020). This reform aimed to separate the vertical integration of retail and wholesale distribution of medicines, which had existed since 1996. The provision of pharmacy services is regulated by the Medicinal Products Act, including provisions for licences, issued and registered by the SAM, which acts as a state supervisory authority. Pharmacists and assistant pharmacists are registered by the Health Board (see sections 5.6 Pharmaceutical care and 6.1.8 Pharmacy reform to strengthen the role of pharmacists).

2.7.5. Regulation of medical devices and aids

The European Commission directives on medical devices were transposed into national law in December 2004 with the introduction of the Medical Devices Act, which replaced several previous acts regulating the sector. The Medical Devices Act and related provisions regulate manufacturing, marketing and advertising of medical devices and provide rules for market supervision. It also regulates the liability of market players for nonconformities, violations and perpetrations. In 2010, the Health Board became the competent authority for medical devices in Estonia (previously the SAM held the listed responsibilities).