-

22 May 2025 | Policy Analysis

Recent attempts at regulating the establishment of self-employed physicians’ practice across the country -

29 January 2025 | Country Update

Introduction of nurse staffing ratios in public hospitals -

31 January 2023 | Country Update

Periodic certification for health professionals

4.2. Human resources

Context

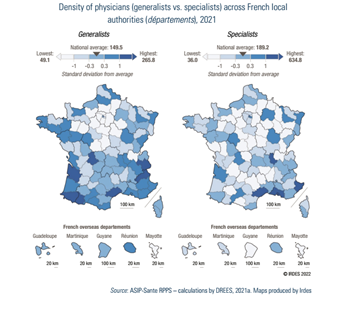

France faces significant and persistent geographical disparities in physician supply. Underserved medical areas remain a longstanding challenge, despite multiple reforms, including financial incentives to encourage physicians to establish practices in these areas.

Impetus and purpose of the reform

Approved by the French National Assembly in May 2025, the “Garot Law” aims to tackle the issue of underserved medical areas – affecting around 9 000 000 people in France – by regulating where self-employed physicians can establish their practices and by mandating their participation in on-call duties. This marks a major shift in a country where physicians have traditionally enjoyed total freedom regarding where and when they practice.

Main content of the reform

The proposal requires all newly qualified physicians to obtain authorization from Regional Health Agencies (ARS) to open a new practice in well-served areas. Authorization is only granted if a physician of the same specialty simultaneously leaves the area. In contrast, the establishment of new practices in underserved areas will be automatically approved. A territorial indicator of healthcare provision for each medical specialty, which remains to defined, will be used to classify areas.

Stakeholder positions

While patient advocacy groups support the “Garot Law”, physician unions and medical students and residents are strongly opposed, perceiving it as a strong constraint on professional freedom and a disincentive to enter medical studies. Nevertheless, similar territorial restrictions are already used for regulating the local supply of other health professionals, such as nurses and community pharmacists, without sparking comparable controversy. The bill is currently under review by the Senate, but its prospects of adoption appear limited given the strong influence of the medical profession on the Senate.

Moreover, the government stated its opposition to the “Garot Law” and has supported an alternative proposition, the “Mouiller Law”, for which it has initiated a fast-track legislative procedure. The text was approved by the Senate in May 2025 and is currently under review in the National Assembly. While this law also aims to regulate the establishment of physicians’ practice, it gives more discretionary power to local authorities in defining the rules for establishment and is seen as less coercive for physicians. The law proposes to maintain free establishment for general practitioners, with the condition that they must participate in mandatory consultations in underserved areas for a few days each month. In contrast, as in the “Garot Law”, specialists would only be allowed to set up practice in well-served areas if replacing a departing specialist, with some possible exemptions. Local authorities (départements) will identify healthcare needs in their areas and define under-served zones where access is difficult as well as over-served zones where the level of healthcare provision is particularly high, after consulting with local and municipal elected officials. Regional health agencies (ARS) will have to take their opinion into account when determining these areas which risk introducing some heterogeneity in decision rules.

Other recent reforms to tackle underserved medical areas

In April 2025, a reform of the nursing profession was adopted to expand the autonomy of nurses. It introduced nurse-led consultations, the right for nurses to make diagnostics, and limited prescribing rights. This legislation highlights a parallel change towards enhanced task-shifting and the expanded role of nurses as additional levers to address geographical healthcare disparities.

Authors

References

- https://www.vie-publique.fr/loi/298457-deserts-medicaux-regulation-installation-medecins-proposition-loi-garot (in French)

- https://www.vie-publique.fr/loi/297628-profession-dinfirmier-proposition-de-loi (in French)

- https://www.vie-publique.fr/loi/298573-acces-aux-soins-deserts-medicaux-medecins-proposition-de-loi-mouiller (in French)

Authors

4.2.1. Planning and registration of human resources

According to the Public Health Code of 2021, there are three categories of health professionals in France:

- medical professionals: physicians, midwives and odontologists/dentists (art. L4111-1 to L4163-10);

- pharmacists (including assistants) and medical physicists (art. 4211-1 to 42); and

- medical auxiliaries (also called allied health professionals): nurses, physiotherapists, chiropodists/podiatrists, occupational therapists and psychomotor therapists, speech therapists and orthoptists, medical laboratory technicians, hearing aid technicians, caregivers, child care auxiliaries and ambulance attendants (art. 4311-1 to 4394-3).

Nurses, physiotherapists, chiropodists/podiatrists, occupational therapists, psychomotor therapists, speech therapists, orthoptists and medical radiology technicians are legally defined with a list of “procedures” that they are authorized to perform. Social care professionals such as social service assistants and psychologists, as well as professionals such as osteopaths and chiropractors, are not considered as health professionals according to the Public Health Code.

The MoH is responsible for human health resource planning at the national level, whereas the ARS are responsible for implementation and organization at the local level. The National Observatory of the Demography of Health Professions (Observatoire national de la démographie des professions de santé, ONDPS), created in 2003, has the mission to collect data and provide guidance on human resources in the health care sector.

Training of medical professionals is carried out in 34 medical faculties, 24 pharmaceutical faculties, 15 faculties of dentistry and 34 midwifery schools (ONDPS, 2021). Several professions in the health care sector (physicians, pharmacists, dentists, midwives, nurses, paramedics, etc.) have been, for the past 50 years, regulated by the numerus clausus or by quotas, which both represent a fixed number of students that can be admitted to the first or second year of studies for health professions for each university. The last numerus clausus and quotas, set in 2020 by the ministries of Health and Higher Education, were 9361 medical, 1322 dentistry, 3265 pharmacy, 1039 midwifery, 31 764 nursing and 2865 physiotherapy students (OMK, 2021; ONDPS, 2021). The numerus clausus focused only on training capacity and lacked regional-level consultation, hence failed to oversee population needs and to remedy the disparities in health care provision across regions. The system was abolished in 2021 as part of the 2019 OTSS, shifting the focus of human resource planning to meeting anticipated population needs. For the first time the number of medical students (including physicians, pharmacists, midwives and dentists) to be admitted was determined in a national conference bringing together representatives from the ARS, professional unions, student associations, medical councils, local decision-makers and the ONDPS. The conference set the training objectives for the next five years (2021–2025) (ONDPS, 2021). Nevertheless, in practice, the criteria for determining the number of students have barely evolved from those previously used to set the numerus clausus (Dumontet & Chevillard, 2020) and this planning does not consider other local human resources such as nurses and allied health professionals.

Health care professionals are not formally licensed in France, but registration with the councils of professionals (Ordre professionnel) is mandatory to be able to practise according to the Public Health Code for the following professionals: physicians, dentists, midwives, pharmacists, nurses, physiotherapists and chiropodists/podiatrists. The councils keep professional registries, promote good medical practice and deontology, and can take disciplinary actions against their members (Adenot, 2012). However, some councils have difficulties functioning properly, in particular the Nursing Council, for which the registration rate is only about 50% (Cour des comptes, 2021b) since salaried nurses and facilities that employ them often ignore the obligation of registration. In 2022 the Nursing Council advocated for a more stringent control of the registration of active nurses by the State, as it is difficult to obtain robust estimations of their number, which has a negative impact in policy-making and workforce planning (ONI, 2022). Professionals are included in the national Directory of Healthcare Professionals (Répertoire partagé des professionnels de santé, RPPS) through their Council, which gives them a unique professional identifier. Nurses have been included in this directory only since October 2021. Most other professionals working in the health sector (such as psychologists) are also obliged by law to be registered, but via the ARS, with the noteworthy exception of nursing aides (ANS, 2021).

In France there was no compulsory recertification system in place for health professionals. However, as of January 2023, physicians, dentists, pharmacists, midwives, nurses, physiotherapists and chiropodists/podiatrists will be recertified every six years (with a longer delay of nine years for already practising physicians). This new certification process aims to guarantee that professional skills, care quality and scientific knowledge are upheld and will rely on a list of criteria set up at the national level (including compulsory continuous training determined by professional councils) (Bill no. 2021-961 of 19 July 2021; Order of 7 September 2022). The professional councils will be responsible for the recertification, although this has been criticized by patient associations demanding an external evaluation.

4.2.2. Trends in the health workforce

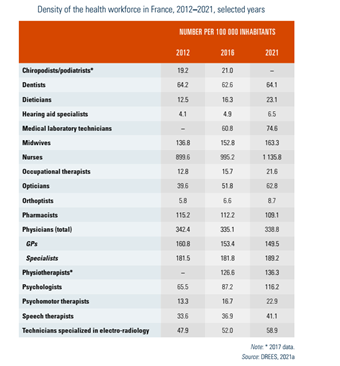

Approximately 1.9 million people, i.e. 7% of the active workforce in France, were working in the health care sector in 2016 (compared to 1.4 million in 2000) (DREES, 2016). The density of the health workforce is presented in Table4.3 (latest year available).

Table4.3

Given the anticipated shortage of health care professionals as a result of an ageing workforce and population, the number of trained health care workers has increased over time for most health care professions, although for some professionals, especially GPs, the pace of increase is considered insufficient (CNOM, 2020a).

The number of women has been increasing in medical professions among younger generations: in 2021, 62% of physicians aged under 40 years were women, compared to 48% of all physicians (Anguis et al., 2021). Some professions have historically been female-dominated and remain so in 2021; the highest proportions of women can be found among midwives (97%) and nurses (87%), followed by pharmacists (68%) (DREES, 2021a). The majority of workers with a part-time professional activity in the health sector are women (ONP, 2021a), which is similar to other sectors, such as education and child care (Vie publique, 2021).

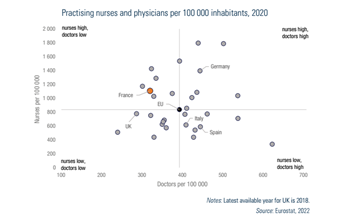

France has a relatively high number of nurses in relation to physicians. In 2020 there were 318 practising physicians and 1134 practising nurses per 100 000 inhabitants (Fig4.3). However, the distribution of nurses across sectors is unequal. In 2020 there were 4.3 nurses for one physician in the hospital sector compared to less than one (0.8) nurse per physician in the primary care sector (DREES, 2021a). The number of physicians per 100 000 inhabitants in France is lower than the EU average (393 per 100 000 inhabitants), and lower than in Germany, Italy and Spain, whereas the number of nurses per 100 000 inhabitants is higher than the EU average (837 per 100 000) and higher than in Italy and Spain, but lower than in Germany (Fig4.3).

Fig4.3

The French health system has historically been physician-centred. However, the roles and responsibilities given to allied health professionals have been increasing in recent years to meet the needs of an ageing population. Task shifting between GPs and other health professionals has been encouraged since 2009. In addition, for supporting the primary care workforce, a new health profession, named “medical assistant”, was created in 2019. Medical assistants can be hired by self-employed physicians (with financial aid from the SHI) to assist with administrative tasks and care coordination. These positions are open to both people with a health professional background (such as nurses or nursing aides) and those without (such as medical secretaries) (CNAM, 2019). By 2022, 3122 medical assistant contracts were signed, mainly by GPs (80%) or physicians working in underserved medical areas (around 50%) (CNAM, 2022a). Advanced nurse practice is also under development (see subsection Nurses) to enhance task shifting. However, obstacles remain for task shifting among self-employed professionals paid on an FFS basis, since it represents an economic risk for physicians who can experience a loss in revenue when shifting tasks to nurses (Or & Gandré, 2021).

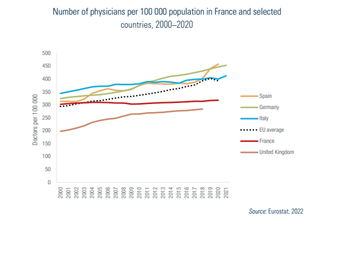

Physicians

In 2000 there were 302 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants in France, which was slightly above the EU average of 297 per 100 000 inhabitants. However, between 2000 and 2020 the number of physicians increased more slowly in France than in other EU countries. Therefore, while the density of physicians was higher in 2020 (318 per 100 000 inhabitants) than in 2000, it remained lower than the EU average (393 per 100 000 inhabitants) (Fig4.4).

Fig4.4

In January 2021, 227 946 physicians were actively practising in France, including physicians with a regular activity (activité régulière), intermittent activity (mostly replacement physicians in the self-employed sector or with short-term salaried contracts) and retired physicians still in active practice. Of all active physicians, 44% were GPs and 56% other medical specialists (127 325 practising specialists against 100 621 GPs) (DREES, 2021a). The most common specialization is psychiatry, followed by surgery (Anguis et al., 2021). The majority (56%) of all active physicians are self-employed or combining their work with shifts or part-time employment in hospitals. Self-employment is more common among GPs (57%) than specialists (34%), and less common in younger generations and among women. In 2021 one third of all physicians were salaried in hospitals (19% of GPs and 41% of specialists), and 13% in other health care facilities such as health care centres or LTC homes for the older population and the disabled (DREES, 2021a). The number of physicians who are exclusively salaried has increased by 12% since 2010 (CNOM, 2020a), partly as a result of different forms of group practices becoming more popular (see Chapter 5). In 2022, 69% of all self-employed GPs (87% of those under 50 years old) practised in a group. However, this mostly means that they share their office space with another GP; only 40% of them were in practices including other health professionals (Bergeat, Vergier & Verger, 2022). There are over 1300 MSPs in France, employing an average of five GPs per practice (see section 5.3) (Chevillard & Mousquès, 2021) and 2200 health care centres, of which 21% have a pluri-professional activity (DGOS, 2021a).

In January 2021 the mean age of practising physicians was 51 years, and one third of all active physicians were over 60 years old (DREES, 2021a). Due to changes allowing physicians to continue working after retirement (while keeping their pension) (CNOM, 2013), the share of retired physicians in active practice has increased, representing 9% of all physicians with a regular activity in 2020 (CNOM, 2020a). While the number and density of medical and surgical specialists have increased between 2012 and 2021, the number and density of GPs have decreased. Taking into account predicted changes in the demography and health care needs (such as population growth and ageing), the GP density is expected to decrease until 2028, and is predicted to return to 2021 levels in about 2035 (Anguis et al., 2021; see also Box4.2 and Fig4.5).

| Box4.2 | Fig4.5 |

|  |

Nurses, Nursing aides and midwives

Nurses

Nurses constitute the highest number of health care professionals in France. In January 2021 there were 764 260 nurses, with an average age of 46 years. However, this may be an overestimation of actively practising nurses, since the number of nurses under 62 years old (average retirement age in France) was 637 000 at the same date. The fact that nurses are not systematically registered complicates the estimations of the active workforce. The majority of nurses work as salaried staff in hospitals (60%); about 20% are self-employed or have a mixed activity in the ambulatory sector, and the rest are salaried in other health care structures, especially in LTC ( DREES, 2021a).

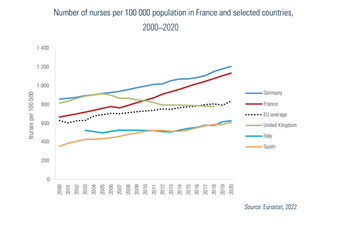

Similar to Germany and Spain, the number of nurses per 100 000 inhabitants (based on Eurostat data) increased in France between 2000 and 2020, from 666 to 1134 (+70%). The increase has been steeper than for the EU average (from 629 to 837 per 100 000, +33%) (Fig4.6). However, the density of nurses (nurses per capita) should be compared with caution across countries, due to large differences in nursing education and roles.

Fig4.6

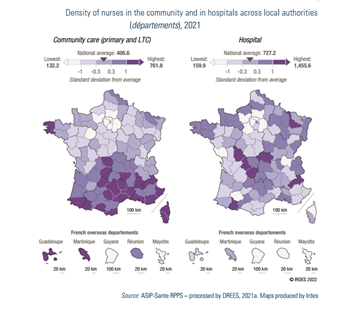

According to national data, in 2021 the density of nurses was 1133 per 100 000 inhabitants (DREES, 2021a).While the number of nurses is high in the hospital sector (727 per 100 000 inhabitants), it is significantly lower in the primary and LTC sectors (407 per 100 000) (DREES, 2021a; see also Fig4.7).

Fig4.7

Since 2009, opening a new nurse practice in overserved areas[4] is subject to restrictions for ensuring an equal distribution across French territory (ARS, 2021). Financial incentives are also used to attract nurses to underserved areas (CNAM, 2020b; Duchaine, Chevillard & Mousquès, 2022).

In 2019 the relative wages of nurses in public hospitals were among the lowest in the OECD countries (OECD, 2019a). There were several protests and strikes in public hospitals in the months before the Covid-19 pandemic denouncing the hard working conditions, especially of allied health professionals (Or et al., 2021). Following the pandemic the MoH launched a reform package (Ségur de la santé) for improving the working conditions of 1.5 million health professionals in acute and LTC facilities. Wages of all categories of health professionals increased between, on average, 15% and 20% as of October 2021 (MoH, 2021k).

The role of nurses in health care provision is still restricted in France compared to many other countries, with limited responsibility and career options. However, this is slowly evolving. In the primary care sector pilot projects have been set up since 2004 to improve care for patients with chronic conditions (Action de santé libérale en équipe, ASALEE). In these pilots nurses are allowed to perform new procedures and tasks that are usually provided by GPs, including screening and therapeutic education for patients with some chronic diseases (such as diabetes) (Fournier, Bourgeois & Naiditch, 2018). An advanced practice nurse (Infirmier en pratique avancée, IPA) position, broadening nurses’ responsibilities and facilitating task shifting, was introduced in 2019. The IPAs can follow up and screen patients with common chronic conditions (such as diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease), and from 2021 onwards patients with cancer, chronic renal disease or mental disorders. They are also able to specialize and work in emergency wards from 2022 onwards (Nayrac, 2021b). IPAs can renew medical prescriptions for their patients (Public Health Code of 20 July 2018). However, they can only see patients referred by a physician with whom they previously signed a formal agreement, which limits their autonomy and the attractiveness of this new profession. The IPA training is designed for experienced nurses (at least three years of professional experience) and requires four additional semesters of full-time studies, equivalent to a master’s degree (Code of Education on 18 July 2018).Yet their wages/tariffs are barely higher than those of regular nurses, and the fact that both these nurses and physicians are self-employed and are paid by FFS creates competition where physicians may be reluctant to delegate certain tasks. The first 63 IPAs graduated in 2019, another 920 graduated in 2020–2021 and 729 more were expected to graduate in 2022 (Bohic et al., 2021). However, at the end of 2021, only 674 IPAs were registered to the Nursing Council, of whom the majority (562) were salaried. A recent report from the public audit office pointed out the need for expanding the scope of responsibilities of IPAs with a possibility of direct patient access to their services, while indicating the positive impact of the first IPAs on quality of follow-up and patient care (Bohic et al., 2021).

Nursing aides

In 2017 the number of nursing aides was estimated to be around 390 000 (DGOS, 2018). The majority work in hospitals (around 245 000), primarily in the public sector (76% of all nursing aides working in hospitals) (DREES, 2021c). This profession suffers from a lack of attractiveness. The number of students enrolling to nursing aide training has been declining recently (–6% in 2018 compared to 2016) (Croguennec, 2019). In addition, recruitment difficulties have been underscored in nursing homes. Almost half of all residential nursing homes (44%) report difficulties in recruiting personnel: 9% of all nursing homes and 16% of private for-profit homes have vacant positions for nursing aides (vs 4% in both cases for nurses) (Bazin & Muller, 2018). The Ségur de la santé reform was intended to increase the wages of nursing aides to the European average, with an immediate minimum monthly increase of €183 net after deducting taxes and a global long-term increase in salary scales (MoH, 2021h). While this represents a 15% wage increase for a nursing aide with less than one year of experience, the salaries remain very low considering their working conditions. A reform aiming to promote this profession is also under way, which will improve the curriculum by increasing the length of study from 41 to 44 weeks with more theoretical content (Order of 10 June 2021).

Midwives

Midwives are distinct medical professionals; they have five years of training and are licensed by their professional council (Ordre des sages-femmes). In January 2021 there were 23 541 actively practising midwives in France with an average age of 42 years. The majority of midwives (59%) are hospital employees, and approximately 23% are exclusively self-employed (DREES, 2021a). Midwives can also work in ambulatory child and maternal health centres performing screening and follow-up (Anguis et al., 2021). An increasing number of midwives are at least partially self-employed (34%) to have wider possibilities to exercise their profession, including involvement in gynaecological follow-up, abortion, vaccination, perinatal rehabilitation, contraception, health promotion and drug prescription (limited list) (Anguis et al., 2021; ONDPS, 2021). Recent reforms will also grant midwives the authorization to prescribe certain drugs and to refer their patients to specialists (Law no. 2021-502 of 26 April 2021).

In January 2021 there were 163 midwives per 100 000 women aged 15–49 years in France, and the density varied between 131 and 254 per 100 000 women across regions (DREES, 2021a). The number of midwives has steadily increased over the past decade (+3% a year between 2012 and 2017 and +1% a year since 2017) (ONDPS, 2021), faster than the number of potential deliveries, due to a high numerus clausus (Anguis et al., 2021). Similar to nurses, opening new practices in areas with a high density of midwives is restricted (CNAM, 2020c).

Pharmacists

In January 2022 there were 74 039 active pharmacists in France, with an average age of 47 years (ONP, 2022). Approximately 40% were self-employed. The majority (70%) of pharmacists work in community pharmacies (half own their pharmacy and half are salaried) (ONP, 2021a). About 10% of pharmacists work in hospitals or other health care facilities (DREES, 2021a) and 10% work in the pharmaceutical industry or in other sectors (Anguis et al., 2021).

The density of pharmacists, 109 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2021, exceeds the recent OECD average (86 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2019) (OECD, 2021a). Pharmacists are spread rather evenly across the metropolitan territory with a density varying between 92 and 126 pharmacists per 100 000 inhabitants, due to a strict regulation of authorizations for new pharmacies, but are more dispersed in the overseas departments (between 33 and 108 per 100 000 inhabitants) (DREES, 2021a).

Psychologists

In January 2021 there were 78 197 actively practising psychologists in France (a number which has been steadily increasing), with an average age of 46 years. Approximately half of psychologists are at least partially self-employed (36%) or hospital employees (21%), whereas 44% work in other sectors, such as the social care sector (for instance, child welfare). In January 2021 the density of psychologists was 116 per 100 000 inhabitants, varying between 98 and 151 per 100 000 in metropolitan France and between 21 and 85 per 100 000 in overseas departments (DREES, 2021a). In France psychologists are not considered health professionals in the Public Health Code. As a consequence, consultations with self-employed psychologists in the ambulatory sector are not reimbursed by the SHI, they do not have a professional council and their practice is little regulated (Gandré et al., 2019). Self-employed psychologists have a limited role in the public mental care strategy, which has historically been hospital-centred. However, the mental health consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic have triggered reforms in this area (see section 5.11).

- 4. Nurse practices in overserved areas are defined by ARS, mainly as a function of the age–sex adjusted number of full-time equivalent of nurses per 100 000 inhabitants. ↰

4.2.3. Professional mobility of health workers

Recent workforce planning takes into account the flow of medical professionals emigrating and immigrating from/to France (OECD, 2019b). France is a net receiving country for foreign-trained health professionals, while emigration of French-trained professionals to other countries is limited. Of all active physicians under 70 years old in 2021, 10% had a diploma from a foreign country, compared to 7% in 2012 (Anguis et al., 2021). The proportion of physicians with a foreign diploma is higher among specialists (14%) compared to GPs (5%) (Anguis et al., 2021). More than half (53%) of all foreign diplomas were obtained in another EU country, primarily Romania (43%) – where training programmes are available in French – but also Belgium (15%) and Italy (14%). Physicians from non-EU countries come mainly from the Syrian Arab Republic, Morocco or Tunisia (Anguis et al., 2021), and they are more likely to work in underserved medical areas (OECD, 2019b). The proportion of foreign diplomas among active midwives is 8% (of whom 90% are French nationals), and 2% for pharmacists (Anguis et al., 2021). The share of allied health professionals with a foreign diploma is relatively high among physiotherapists and speech therapists, mainly driven by French nationals who studied abroad (DREES, 2016; OMK, 2021), and very low for nurses (3%, compared to 15% in the United Kingdom and Switzerland) (DREES, 2020c).

Health professionals with EU diplomas are entitled to the same rights as French-trained professionals, while those with diplomas from outside the EU are subject to stricter standards and can only practise after passing an exam validating their professional mastery.

4.2.4. Training of health personnel

The government (the ministries in charge of health and higher education) decide the educational standards, how they are attained and the entry requirements for the initial training of health personnel.

All students who have successfully completed upper secondary education can apply to the first year of medical, pharmacology, midwifery or dentistry school (Law no. 2018-166 of 8 March 2018). Until 2020 all medical, dentistry, midwifery and pharmacy students had a common first year of studies in the medical field (première année commune aux études de santé, PACES), followed by selective entry exams for the second and remaining years, with a limited number of places determined by the numerus clausus for each field. The PACES was abolished in the 2019 OTSS (Law no. 2019-774 of 24 July 2019) and replaced by two options: a health-specific track (parcours spécifique accès santé, PASS) and a possibility to study medicine as part of other bachelor’s degree programmes with a health option (Licence accès santé, LAS). The PASS resembles the former first year of medical school with majors in health and a non-health minor. The LAS allows bachelor’s degree students with other majors, such as law, to apply for the second year of medical school after one completed year of studies with a health minor. The LAS is available in all universities, thus improving the geographical access for entering medical school. Entry to the second year of medical school is based on grades obtained during the first year and oral exams (Decree no. 2019-1126 of 4 November 2019).

Medical school for physicians consists of three cycles. The first cycle lasts three years (including PASS or LAS). The second cycle, also lasting three years, consists of theoretical and clinical practice (mainly in teaching hospitals), followed by a specialization after a selection process (third cycle). Recent reforms have changed this final selection process by abolishing the competitive national exam at the end of the second cycle (Épreuves classantes nationales, ECN). The selection now focuses more on students’ clinical skills and experience in their specialty of choice (i.e. internship) (Law no. 2019- 774 of 24 July 2019) (MoH & Ministry of Higher Education and Research, 2018b). The third cycle consists of 3–6 years of residency (Internat) depending on the specialization. During the last year of the third cycle, the students gain more autonomy and are considered as junior physicians (Docteur junior) and are allowed to work as short-term replacement physicians (Médecin adjoint) in underserved regions. Medical students in general practice must spend at least six months of their last year of postgraduate training in ambulatory care settings, which are primarily offered in medically underserved areas (Law no. 2019-774 of 24 July 2019). The measure will be extended to other medical specialties over time.

Training of pharmacists and dentists takes six to nine years at university, depending on the specialty chosen. Midwives undergo at least five years of university training, while nurse training takes a minimum of three years. The competitive national entry exam to nursing schools was replaced in 2019 by an evaluation of applications by each faculty (MoH & Ministry of Higher Education and Research, 2018a). There are not many specialized nurses in France, but specialization is possible in a few areas (operating room, nursery, anaesthesia and, more recently, advanced nurse practice) with one or two additional years of study at university (see section 4.2.2). In addition to the initial training, nurses must have two years of clinical experience in a hospital setting to qualify for self-employed status.

In France the training of allied health professionals has traditionally been fragmented across secondary schools, training institutes and universities. As opposed to many other European countries, allied health professionals were not awarded a standard university degree until 2006, when the training of these professionals was aligned with the European university system (Brunelle & Queneau, 2015). Physiotherapists, whose training passed from three to five years in 2015 (Nayrac, 2021a), were the first to be granted a master’s degree in 2021 (Decree no. 2021-1085 of 13 August 2021). The training of psychologists, who are not considered as health professionals by the Public Health Code, is not well regulated. Therefore, there is heterogeneity in curriculums across universities, sometimes with insufficient clinical training (Emmanuelli & Schechter, 2019; Gandré et al., 2019).

Continuous training of health professionals will progressively become compulsory in the framework of the new recertification system, which has been introduced since January 2023 (see section 4.2.1).

In France, no compulsory re-certification system was in place for health professionals, until recently. Starting in 2023, physicians, pharmacists, dentists, midwives, nurses, physiotherapists and podiatrists will be required to recertify every six years (with an initial longer delay of nine years for already practicing professionals).

This new certification process aims to guarantee that professional skills, care quality and scientific knowledge are upheld. This process will rely on a list of criteria set up at the national level, including compulsory continuous training. The professional councils will be responsible for the re-certification, with the help of the French health authority (Haute autorité de santé, HAS), while patient associations would have preferred an external evaluation.

More information here (in French): https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000043814566; https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3353194/fr/proposition-de-methode-d-elaboration-des-referentiels-de-certification-periodique-des-professions-de-sante-a-ordre

Authors

4.2.5. Physicians’ career paths

After graduation, physicians can choose to set up a practice as self-employed practitioners, for whom the career paths are limited, or become salaried employees in hospitals or in other health care facilities.

To pursue a career within public hospitals, physicians are employed as hospital practitioners. New reforms, accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, aim to improve the working conditions, remuneration and career paths of physicians working in public hospitals (Ségur de la santé). The reforms significantly increased the wages of hospital physicians, especially the youngest ones, diversified their career paths, simplified the recruitment process in public hospitals and facilitated the recruitment of physicians working in private hospitals. Physicians in public hospitals were also given the possibility to engage in private practice (Bill no. 2021-292 of 17 March 2021). The reform also increased the income of hospital physicians (+€1500) who commit 100% to public service without any private practice.

4.2.6. Other health workers’ career paths

Most other health professionals can work either as self-employed practitioners or as salaried employees, except for nursing aides who can only be salaried. The share of professionals who are self-employed varies according to the health profession. For instance, while nurses (64%) and midwives (59%) are mostly working as hospital employees, most dentists are exclusively self-employed (79%) (DREES, 2021a). Recent reforms aim to evolve the career paths of all health care professionals, including medical auxiliaries, who will be able to mix self-employment with salaried positions (Law no. 2019-774 of 24 July 2019).

Academic and research career paths have long been mainly limited to physicians, dentists and pharmacists. Involvement of other professionals in research activities is slowly increasing but remains marginal despite a dedicated hospital research programme for projects coordinated by nurses and allied health professionals since 2011. Dedicated academic career tracks (assistant professor and professor positions) for nurses and midwives were created officially only in 2019 (Decree no. 2019-1107 of 30 October 2019) (MoH, 2019g). The recent changes allowing allied health professionals to obtain a university degree also allow these professionals to pursue an academic career.