-

21 October 2024 | Country Update

Pharmacists allowed to deliver antibiotics without a physician’s prescription for specific conditions

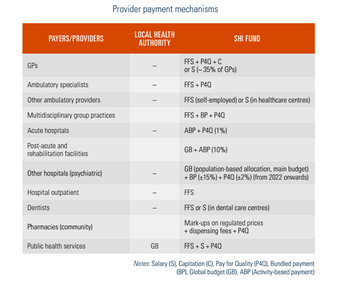

3.7. Payment mechanisms

Most health care providers in France are paid based on volumes: FFS for self-employed health workers and activity-based payments in the hospital sector (see Table3.6). However, it is recognized that these types of payment contribute to increasing volumes of care without forcibly improving quality and coordination of care across settings. Therefore, in recent years new payment models have been implemented and piloted to encourage better quality, coordination and efficiency of care.

Table3.6

3.7.1. Paying for health services

3.7.1.1. Public health services

Funds allocated to collective public health services at the national level are set each year through a parliamentary debate and are mostly made up of funding from the State and local authorities (départements), which funded 51% of public prevention activities in 2019 with some additional funds from the SHI (15%), and private or associative sources (34%) (DREES, 2020a). Funding is allocated at the regional level through ARS, which have the responsibility to develop health promotion and prevention activities on their territory (see section 2.3). Public prevention funds are mainly spent on public health surveillance and disease monitoring (56%) and primary prevention such as occupational health and immunization (32%), followed by secondary prevention such as screening (7%) and public health campaigns (6%). The State is the principal funder of all these activities, except primary prevention, which is mainly funded by the private sector (49% in 2020) (DREES, 2021b).

Individual preventive care provided in ambulatory settings or hospitals is paid by the SHI as part of regular services, via FFS remuneration (for example, dental check-ups for children or young adults, smear tests by gynaecologists, patient education, etc.) (see section 3.7.2). In addition, the SHI runs a network of 85 health examination centres (Centres d’examen de santé, CES), providing preventive health examinations primarily for people who are in a precarious situation, who do not use health care regularly and do not benefit from organized preventive measures such as cancer screening (CNAM, 2020a). The SHI additionally provides a budget to local authorities (départements) for supporting maternal and child health services, free of charge, in local maternity centres (Chambaud & Hernández-Quevedo, 2018). Specific funds can also be allocated to collective public health services by local authorities (départements) and municipalities depending on their priorities.

3.7.1.2 Primary and specialized ambulatory care

Primary and specialized ambulatory services are mostly provided by self-employed health professionals working in solo or group practices. Self-employed physicians and allied health professionals working in the ambulatory sector contract with the SHI fund and are mostly paid by FFS. The prices of the consultations, procedures and services they provide are set at the national level through formal negotiations between the UNCAM, the government, the UNOCAM and the unions of health professionals, which leads to a national collective agreement every five years (although amendments are possible in-between).

The MoH plays a significant role in negotiations between the UNCAM and physicians’ unions, which have significant lobbying power. All health professionals are subject to the terms of the national agreement, except if they expressly choose to opt out, in which case their consultation fees are not reimbursed, but this concerned less than 1% of all physicians in 2019, less than 0.5% of all dentists and less than 0.1% of all midwives and allied health professionals (CNAM, 2021f).

The national collective agreement is a contract which sets the fees for health services in the ambulatory sector. The SHI pays the social contributions, including the pension of physicians who agree to charge patients the nationally negotiated fees (called sector-1 contractors). In 2019 around 72% of self-employed physicians (93% of GPs and 51% of specialists) were sector-1 contractors (CNAM, 2021f). They are generally not allowed to charge any extra fees. Some physicians are allowed by the SHI to charge higher fees (called sector-2 contractors) based on their level and experience. Physicians working as sector-2 contractors are free to charge higher fees but must purchase their own pension and insurance coverage. The amount exceeding the regulated price (i.e. extra-billing) is not covered by the SHI but can be covered by CHI. The creation of sector-2 in 1980 aimed to reduce the cost of social contributions for the SHI fund, but did not have the expected impact, and the demand for the sector was much higher than predicted. Consequently, access to sector-2 has been limited since 1990 mainly to specialist physicians with specific experience (Order of 20 October 2016). While the share of physicians working in sector-2 represented 48% of specialists and 6% of generalists in 2019, these proportions show strong variation across regions and medical specialties. For example, 76% of ophthalmologists were in sector-2 in the Parisian area vs 43% in the Bretagne region (CNAM, 2021f).

The Code of medical ethics (Public Health Code of 22 December 2020; Code of Social Security of 23 December 2021) requires that extra-billing be of a “reasonable” amount. However, until 2012 there was no regulatory definition of the term “reasonable”. This changed in 2012, when the medical professional council defined it as a fee exceeding three or four times the regulated prices. Additional restrictions were also introduced to forbid extra-billing patients with C2S and for emergency care. In 2017 the SHI introduced a new optional and yearly contract to regulate prices charged by physicians in sector-2, called “controlled tariff option” (Option de pratique tarifaire maîtrisée, OPTAM). Physicians in sector-2 who sign this contract commit to freeze their fees (at their average of the three previous years) and not to charge more than double the regulated tariffs. They are also asked to perform a share of their services at the regulated SHI tariff levels. In return, they receive a bonus proportional to the share of their activity respecting the rules. There is also a specific option, with similar modalities, dedicated to specialists performing surgical or obstetrical procedures in private practice or in hospitals (Option de pratique tarifaire maîtrisée chirurgie et obstétrique, OPTAM-CO). In 2020 more than 17 000 physicians, representing half of the eligible sector-2 contractors, signed these contracts (Tranthimy, 2020).

3.7.1.3 Inpatient care

Acute care

Until 2005 two different funding arrangements were used to pay public and private hospitals. Public and most private not-for-profit hospitals had global budgets, mainly based on historical costs, while private for-profit hospitals had an itemized billing system with different components: daily tariffs covered the cost of accommodation, nursing and routine care, and separate payments were made for each diagnostic and therapeutic procedure, with separate bills for costly drugs and physicians’ fees. In 2005 an activity-based payment (ABP) model (Tarification à l’activité, T2A) was introduced to pay all acute care services (including home hospitalization) in public and private hospitals. The ABP aimed at improving efficiency, creating a level playing field for payments to public and private hospitals, and improving the transparency of hospital activity and management (Or, 2014).

Under ABP, the income of each hospital is linked directly to the number and case-mix of patients treated, which are defined in terms of homogeneous patient groups (groupes homogènes de malades, GHM). The classification system used in France was initially inspired by the United States Health Care Financing Administration’s Diagnosis Related Groups classification (HCFA-DRG) but adapted to the French system. The GHM classification has changed three times since the introduction of ABP, passing from 600 groups in 2004 to about 2300 in 2009, and has remained stable since. Assignment of patients to GHM is based on the primary diagnosis and on the surgical interventions provided. The last version (v11) of the classification, which was introduced in January 2009, accounted for 2291 groups (compared with 784 in the previous version), and represented a major change in classification with the introduction of four levels of case severity applied to most GHM. Data on length of stay (LOS), secondary diagnoses and age are used in a systematic way to assess the level of case severity (Or & Bellanger, 2011).

Public hospitals (and private hospitals participating in education and research) receive additional payments (Missions d’intérêt général et d’aide à la contractualisation, MIGAC) to compensate for specific “missions”, including education, research and innovation-related activities, as well as activities of general public interest such as meeting national or regional priorities (for example, developing preventive care). A restricted list of expensive drugs and medical devices is paid retrospectively, according to the actual level of prescriptions made (see section 3.7.1.4). In addition, ARS provide on a contractual basis some funding to hospitals for investments aiming to achieve some quality and efficiency objectives. Finally, the costs of maintaining emergency care and related activities are paid by a fixed yearly grant to cover operating expenses of services for a minimum of 12 500 visits per year; the payment is increased by a certain amount at each additional 5000 visits. In addition, each emergency visit which is not followed by a hospitalization is paid by a fixed fee, which is topped up with payments for consultations and procedures carried out (such as radiology, biological tests, etc.). However, in 2022 the government announced that the payment model of emergency departments will be changed to consider the intensity and quality of emergency care and to improve the coordination of hospital and ambulatory emergency care. The new payment model will consist of a global budget for an estimated activity (which will be calculated considering the patient outflow, mortality and morbidity rates in the local area) and fees adjusted by the intensity of care (40% of the budget), with a small P4Q (2%), which will be based on new emergency quality indicators to be calculated (Order of 6 April 2021).

When the DRG-based payment system was introduced in 2005, the GHM prices were initially based on average costs per GHM (reference costs) calculated from the National Cost Study (Étude nationale de coûts à méthodologie commune, ENCC), separately for public and private hospitals (Or & Bellanger, 2011). The ENCC provides detailed cost information for each hospital stay from about 150 voluntary hospitals (of which 45% are private for-profit institutions), which are able to produce detailed standardized accounting information (ATIH, 2021a). The GHM prices (tariffs) are set annually at the national level. There are two different sets of tariffs: one for public (including private non-profit) hospitals and one for private for-profit hospitals. Moreover, what is included in the price differs between the public and private sectors. The tariffs for public hospitals cover all of the costs linked to a stay (including medical personnel, all the tests and procedures provided, overheads, etc.), while those for the private sector do not cover medical fees paid to doctors (who are paid on a FFS basis) and the cost of biological and imaging tests, which are billed separately. The initial objective of achieving price convergence between the two sectors, which started in 2010 on about 40 GHM (highly prevalent in both public and private hospitals) and was pursued until 2012, was abandoned afterwards.

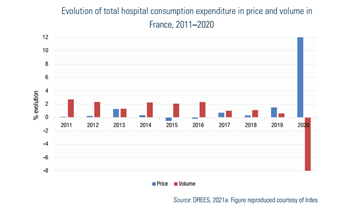

However, the actual prices per GHM are not equal to reference costs. The GHM reference costs (“raw” tariffs) are adjusted, through a complicated and opaque process, to integrate various objectives set by the government each year, considering the overall budget for the acute hospital sector (ONDAM target, see section 3.3.3) and public health priorities. To contain hospital expenditure, national-level expenditure targets for acute care (with separate targets for the public and private sectors) are set by the parliament each year. If the actual growth in total hospital volume exceeds the target, prices go down the following year to stay in the targeted budget. The growth of activity volumes is not regulated at individual hospital level but at an aggregate level (separately for the public and private sectors). Prices have been adjusted downwards regularly since 2006, as the increase in activity has been higher than the targets set (Fig3.6). This also meant that GHM prices were increasingly disconnected from actual costs of care in hospitals.

Fig3.6

Despite a positive trend in productivity of public hospitals since 2004, with a strong rise in case-mix weighted production (Or et al., 2013; Studer, 2012), ABP has also created new problems related to quality and appropriateness of hospital care. Since 2004 both the number of beds per capita and the average length of stay have fallen significantly, with an increase in ambulatory surgeries (DREES, 2021d). However, avoidable hospital admissions, readmissions and emergency visits have increased visibly over this period, especially for older individuals (Bricard, Or & Penneau, 2020). The budgetary management of the sector, which is also adopted at the hospital level, led providers to concentrate on volume rather than on quality objectives. Moreover, there has been a gradual underinvestment in public hospital infrastructure since the hospital prices were intended to cover partly the cost of investment. Underinvestment in public hospital infrastructure and human resources contributed to the degradation of working conditions in public hospitals (DREES, 2019). The Covid-19 crisis aggravated existing problems and highlighted issues with public hospital funding. The MoH aims at progressively reducing the share of ABP in hospital funding, and alternative funding models will be tested (MoH, 2019d, 2020a).

Since 2016 a P4Q programme has been introduced in all acute care hospitals to improve the quality and safety of care (incitation financière à la qualité, IFAQ). This was also extended to rehabilitation facilities in 2017 and to psychiatric facilities since 2021 (CNAM, 2022a). The additional funding is calculated on the basis of a limited number of process indicators (with one patient satisfaction indicator), taking into account the level of these indicators and progress over time. While the funding linked to IFAQ increased over time (0.5% of hospital funding in 2021) and the government aims to increase the share of payment linked to quality, the HAS criticized recently the current P4Q model questioning the relevance of some indicators and the payment rules (HAS, 2022f ).

Post-acute and rehabilitation care

Post-acute and rehabilitation services (Soins de suite et de réadaptation, SSR) were funded until 2017 through an annual prospective global budget for public and private non-profit hospitals and through a daily fixed rate for private for-profit hospitals. Since 2017 the global budgets have been adjusted considering the volume and case-mix of patients. A patient classification has been constructed since 2010, using the logic of GHM as in acute care. There are about 750 groups (Groupes médico-économiques, GME) for services provided in SSR. The GME are determined based on several variables, including principal and secondary diagnoses coded at admission, the patient’s age and level of dependency, post-surgical admission and medical procedures provided. Reference costs for different groups of patients have been estimated and updated annually. The process for fixing these reference costs is similar to the one for the GHM tariffs in acute care based on a cost database of a sample of voluntary hospitals (70 hospitals of which 30 were private) (ATIH, 2021b). The funding reform, which started in 2017, has been implemented very slowly. In 2020 only 10% of the budget came directly from ABPs using GME reference tariffs.

Psychiatric care

Until 2022 psychiatric care in public and non-profit hospitals was funded through an annual prospective global budget (Dotation globale), which was paid by the SHI and allocated by ARS based on historical costs adjusted by the expected annual growth rate of hospital spending, which poorly considered the changes in local mental health needs and created strong geographical inequities. Private for-profit hospitals were paid by daily rates based on the type of care provided (full-time or part-time hospitalization). To reduce geographical and sector-wise inequities, a funding reform has been under way since 2022. The objective is to introduce a “combined” funding model including a population-based allocation to each hospital, based on: local indicators of care needs (poverty and social isolation rates, density of self-employed psychiatrists and social care providers, share of the population aged under 18, etc.); a retrospective budget based on the number of hospitalization days and ambulatory procedures performed per patient per year; allocations for targeted cross-regional activities (for instance dedicated units for patients with complex needs); and a quality-based payment using a list of care quality indicators (under development) (Decree no. 2021-1255 of 29 September 2021).

3.7.1.4 Pharmaceutical care

Outpatient pharmaceutical care is paid according to the official tariffs defined by the CEPS (see section 2.7.4). Expected sales volumes are set for each product through negotiations with the pharmaceutical company, which can agree to refund any excess revenues to the SHI if sales exceed those forecast for the first year following commercialization. Furthermore, there is a short-term macro-level control of drug expenditures regulated by the LFSS (ONDAM; see section 3.3.3), which sets targets of expenditure growth for the drugs reimbursed by the SHI in the following year. This is not a hard budget but a threshold beyond which companies pay discounts to the SHI. However, the total expenditure target does not consider the performance of different drugs in contributing to the overall health system goals and cost reductions (for instance by diminishing the need for hospital care). The costs of drugs that are not included in the list are not reimbursed and their prices are not regulated. These are paid out of pocket by patients and, sometimes, by CHI.

The prices of hospital drugs were set freely in negotiations between pharmaceutical companies and individual hospitals without any regulation until 2004. With the introduction of ABP, most drugs are now included in the GHM tariffs (see section 3.7.1.3). While the prices are not regulated and are still negotiated between the pharmaceutical companies and hospitals, the reimbursement by the SHI is capped at the limit of a maximum fixed tariff which becomes in practice the regulated price. This reference tariff is set according to modalities similar to those used to set the prices of drugs in the ambulatory sector (see section 2.7.4). Furthermore, there are some specific measures for regulating the costs of very expensive and innovative drugs. Their significant costs relative to the GHM tariffs, as well as the need to ensure access to innovation, justified setting a list of drugs for which payments are made on top of the GHM tariffs (Liste des médicaments facturables en sus des prestations d’hospitalisation). These drugs concern mostly the treatment of cancer and autoimmune disorders, and are included on the list based on strict criteria: strong added therapeutic value, cost superior to 30% of the GHM tariff, and medical indication for less than 80% of the patients included in the GHM (DREES, 2021b; Sénat, 2021; MoH, 2021g). A specific targeted budget for these drugs is set in ONDAM (see section 3.3.3), and their prices are regulated via negotiations between each pharmaceutical company and the CEPS mainly using European prices as a reference. In principle, this procedure is a temporary option for funding innovative drugs (once a drug is part of the regular treatment it should be included in the GHM tariff ), but in practice very few drugs were dropped from the list over time (Gandré, 2011; Sénat, 2021). Expenditure for these drugs increased by around 40% between 2011 and 2017, reaching €3.5 billion; 10 drugs (out of 98) accounted for two thirds of this expenditure (DREES, 2021c). Some costly medical devices are also included in the list, representing a total cost of €1.9 billion in 2017.

3.7.2. Paying health workers

Health care professionals are paid differently according to whether they are self-employed or employed in a facility. In the ambulatory sector payment modes of professionals have been diversified over time to align financial incentives with the objectives of care quality and coordination.

3.7.2.1 Primary care physicians

Most primary care physicians are self-employed and, historically, were paid by FFS. The SHI regulates closely the prices of services but there is no regulation of volumes of ambulatory services and prescriptions provided. Health care providers tend to increase the volume of services they provide to maintain or increase their revenues. Also, FFS payments give little incentive to GPs to provide health promotion and disease prevention activities, nor to comply with efficiency objectives. The 2004 gatekeeping reform (see section 5.2), which aimed to reinforce GPs’ role as primary care providers to improve care coordination and efficiency, did not alter the payment mode of GPs but added new payment mechanisms. GPs working as “referring physicians” receive an annual payment of €40 for drafting a care protocol for patients with chronic diseases. Since 2013 they have also received €5/year for each patient in their list. The gatekeeping reform had, however, little visible impact on GPs’ medical practice concerning prescription habits, preventive action and respect of guidelines (Cour des comptes, 2013; Dourgnon & Naiditch, 2010).

Therefore, in 2009 the SHI introduced a P4Q contract (Contrat d’amélioration des pratiques individuelles, CAPI) to improve the clinical quality of care and encourage prevention and generic prescription. Initially proposed to primary care physicians and signed on a voluntary basis, this contract was generalized to all GPs in the 2011 national collective agreement, which stipulated that the payment of primary care providers could be related to their performance. Initial quality objectives included improving prevention rates (for example, flu vaccination uptake, breast cancer screening), reducing the prescription of benzodiazepine drugs (potentially dangerous and addictive) for individuals older than 65 years, better management of diabetes and high blood pressure following clinical guidelines and better generic prescription rates (Bousquet, Bisiaux & Ling Chi, 2014).

The P4Q scheme was renamed in 2012 as the “payment for public health objectives” (rémunération sur objectifs de santé publique, ROSP) and extended to specialists. Some objectives, such as organization of office practice and electronic records, are common to all physicians; others concern only GPs (CNAM, 2021g). Physicians are allowed to opt out of this scheme by writing to their local health insurance fund in the three months following the adoption of the national collective agreement (UNOCAM et al., 2016).

In 2020 the SHI fund reported that about 74 000 physicians (of whom more than two thirds were GPs) had received some performance payment of about €3700 on average that year (about €5000 on average for GPs) (CNAM, 2020b). It is estimated that P4Q accounted for 13% of GPs’ remuneration in 2017 compared to 6% in 2008 (DREES, 2020a). However, the impact of these additional payments on quality of care has not been evaluated to date and the achievements in terms of prevention and efficiency of drug prescription remain modest (CNAM, 2022a).

GPs also increasingly work in health care centres on a salary basis (see section 5.3). In 2021, 19% of GPs were salaried in hospitals and 16% in other health care facilities such as medical centres or LTC homes for the older population and the disabled (DREES, 2021a).

3.7.2.2. Other ambulatory care providers

Other ambulatory care providers, including self-employed specialists, dentists and allied health professionals, are also predominantly paid based on FFS. Even if the P4Q scheme (ROSP) has been extended to specialists (in particular, cardiologists, gastroenterologists, endocrinologists, diabetologists and nutritionists) with dedicated indicators (CNAM, 2021i), the share of P4Q in their remuneration remains small. Allied health professionals also often work in different forms of ambulatory care centres and are therefore paid on a salary basis.

3.7.2.3 Community pharmacists

Pharmacists in community pharmacies are paid by the SHI based on a mixed system combining a digressive sliding-scale margin based on the price of each drug, a fixed-sum per drug box sold and, since 2015, per prescription (with higher amounts for specific population groups, such as young children or older individuals, and for a higher number of drugs on the prescription). Since 2012 pharmacists have also been included in a P4Q scheme to incentivize, in particular, development of electronic pharmaceutical files, provision of advice to specific patient groups (asthmatic patients and those treated with anticoagulants) and generic substitution (CNAM, 2021b), for a total yearly amount estimated at around €7000 per community pharmacy in 2017 (Le Quotidien du médecin, 2018). Owners of community pharmacies may also employ salaried staff (including some pharmacists and pharmacy technicians).

3.7.2.4 Health professionals working in hospitals

Physicians and allied health professionals working in public hospitals are salaried civil servants. They are paid differently depending on whether they have an academic affiliation. Academics are remunerated for clinical practice as well as for teaching and research activities. Full- or part-time hospital practitioners and external practitioners with irregular/intermittent activities are remunerated based on the time worked, and receive allowances for being on call. University hospital physicians are allowed to devote a part of their working time to private practice within the public hospital. These remunerations, based on FFS, are received by the hospital administration, which transfers them to the physician after withholding fees for use of facilities. The salaries in public hospitals are set on a national scale based on seniority and have long been criticized for being unattractive for health professionals. Recent reforms in 2021 increased the salaries of all hospital workers, between 15% and 20% on average, and eased the conditions of private parallel practice for physicians in public hospitals (see section 6.1) (MoH, 2021h).

Physicians working in private hospitals are paid on FFS with often a possibility to extra-bill. Most other hospital professionals are paid on a salary basis.

Experiments with new payment models

Recently, there have been several attempts to modify the current payment models for supporting care coordination, teamwork, task shifting and more integrated care pathways.

In the ambulatory sector multidisciplinary group practices (maisons de santé pluriprofessionnelles, MSPs) have been supported with bundled payments tied to certain quality objectives since 2010 (see section 5.3). These include a lump sum per patient, given to the practice, to remunerate care coordination, interprofessional cooperation, better accessibility (opening hours) and quality of care (Cassou, Mousquès & Franc, 2021; Mousquès & Daniel, 2015).

In 2019, to encourage new care models based on new payment modes, local health care experiments were launched with a dedicated budget (Article 51 of the 2018 Social Security Financing Act). Regulatory barriers to test innovations in payment and care organization are waived for encouraging bottom-up proposals. All health professionals and health care facilities were given the possibility to create and pilot new health care organizations and propose alternative funding models, provided that they aimed to improve quality of health and social care services and patient experience.

Three models are being piloted by the SHI, in a top-down approach. The first model (lump sum payments for teams of health professionals, Paiement forfaitaire en équipe de professionnels de santé, PEPS) is being piloted within MSPs or health care centres interested in replacing FFS for GPs and nurses by a fixed annual payment per patient to follow all the patients of a referring physician, or certain specific populations (older people, diabetic patients, etc.). This model is the one which could bring the most significant changes in the long term, as it aims to replace FFS in primary care by a type of capitation model (DGOS, 2021d). The second model (incentive for shared care, incitation à une prise en charge partagée, IPEP) is a P4Q-type payment to be shared between volunteering care providers across settings; a group of care providers from hospital ambulatory and social care sectors will receive extra payments to share, on top of their usual funding, based on their performance measured by a set of indicators of care quality, patient experience and cost control. Involved care providers must create a patient pool of at least 5000 patients and define joint actions to improve, for instance, access to care, care coordination and prevention. The P4Q does not replace but is additional to the traditional FFS (MoH & CNAM, 2019). Finally, the third model (Épisode de soins, EDS) is an episode-based funding system (for hip and knee replacements and cancer surgery) being piloted in selected hospitals for improving care pathways, coordination and efficiency (DGOS, 2021c). The episode-based payment covers the period of 45 days pre-surgery to six months post-surgery and includes the remuneration of all involved professionals in the hospital and ambulatory setting, replacing FFS for each professional separately (DGOS, 2021c). These models are being piloted between 2019 and 2024 and will be evaluated before any conclusions are drawn (DGOS, 2021c; MoH & CNAM, 2019).

In 2023, the Social Security Financing Act introduced the possibility for community pharmacists to deliver antibiotics for specific conditions without a physician’s prescription, provided that they had undergone a four-hour training program. This measure has been implemented by decree since June 2024. These specific conditions include streptococcal bacterial throat infection (group A streptococcal infection) and acute uncomplicated cystitis in women. The dispensing of antibiotics by pharmacists for these two conditions is contingent upon the positivity of a rapid diagnostic orientation test (swab test or urinary test based on the suspected condition) and the absence of any indication of severity or emergency of illness in the patient. This measure aims to support task shifting from general practitioners to pharmacists for the care of common infections, particularly in medically underserved areas where it can be challenging to secure a prompt appointment with a general practitioner. Additionally, it aims to reduce the misuse of antibiotics by ensuring that they are only delivered when the requisite criteria are met.

More information (in French):