-

25 November 2024 | Policy Analysis

A comprehensive mosaic reform to strengthen primary and chronic care capacity

6.1. Analysis of recent reforms

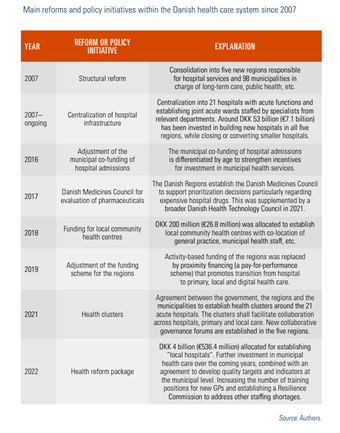

A series of reforms have restructured the Danish health care system since the 1970s. An overview of reforms and policy initiatives until 2012 have been described in detail in previous editions of this Health System Review (Pedersen, Christiansen & Bech, 2005; Strandberg-Larsen et al., 2007; Olejaz et al., 2012). A brief overview of changes since 2007 is also provided in Table6.1, and the details are given below.

Table6.1

Danish health reforms since 2007 can be seen in the light of a health policy style that tends to be pragmatic and instrumental rather than ideological. Health care professionals play a critical role in negotiated agreements and collaborative forums involving state, regional and local governments. This has facilitated reform processes incorporating different stakeholder perspectives, while the economic imperatives and awareness of future challenges have created pressure to find new solutions.

Health policy since 2007 has mostly been about optimization, innovation and incremental adjustments within the existing framework, rather than radical changes to the fundamental pillars of the universal, tax-funded health system (Vrangbæk, 2021). Under the surface of this seeming stability, there have been gradual but profound changes in the governance dynamic. The state has gradually increased its steering capacity through tighter economic management based on a budget law with automatic sanctions, specialty planning, guidelines and quality indicators. The state is also critical for developing and maintaining the digital infrastructure that is a prerequisite for many new initiatives. Meanwhile, the state continues to depend on regions and municipalities to manage service delivery and implement policy initiatives. This is even more important in the ongoing efforts to shift the locus of chronic care from hospitals to primary and local care – and more generally, to address the increasing pressure on the health system due to the ageing population.

Context

The Danish government announced a political agreement on a healthcare reform on 15 November 2024, backed by a broad coalition of the three governing parties (the Social Democratic Party, the Liberal Party, and the Moderates) and four additional parties from across the political spectrum. Two comprehensive reports from expert commissions, presented in November 2023 and May 2024, form the basis of the agreement.

Impetus and main purpose of the reform

The agreement is a response to the emerging challenges related to changing demographics and shortages of healthcare professionals in some areas. The reform is an effort to move focus and resources from hospitals and specialized care towards primary, digital, and home-based care.

Main components

- The number of regions will be reduced from 5 to 4, with the Capital Region and Region Zealand merging into one large region covering Zealand and adjacent islands. The new Region East Denmark will have 2.7 million inhabitants, approximately half of Denmark’s population.

- A new governance structure of 17 collaborative “health councils” (Sundhedsråd) is added to the existing structure. Comprising politicians from regional and municipal councils, they will function as sub-councils to the regional councils, from which they will receive funding. A significant portion will be earmarked for developing primary, local, and digital care as well as supporting the transition from hospital care. The health councils will assume operational responsibility for health and hospitals from the regional councils and specialized home nursing, rehabilitation, and local acute care from municipal councils. The regions remain responsible for hospital planning.

- General practice will remain a key component as gatekeepers and care managers in the new structure. The state will play a stronger role in planning the distribution of general practitioners (GPs) and specialists to ensure nationwide coverage. The government is planning several initiatives to tackle GP shortages, including educating 1500 new GPs, bringing the total to 5000 by 2035. Furthermore, the regions will be allowed to establish region-owned clinics or use public bidding for vacant clinics. The GP remuneration model will also be adjusted to differentiate fees according to demographic and health risk profiles.

- The delivery of specialized home nursing, rehabilitation, and local acute care will be moved from the municipalities to the regions.

- Chronic care packages will be developed for COPD, diabetes, lower back pain, cardiovascular diseases, and patients with complex multimorbidity.

- A national agency will be established to oversee digital health, data infrastructure, and innovation projects.

- Psychiatric and somatic care will be integrated organizationally, with the regional and health councils taking the lead in advancing the implementation of a 10-year psychiatry plan.

- A new national public health law will be introduced.

- A National Prioritization Council will be established to promote cross-sector, transparent, and systematic prioritization across primary and specialized healthcare.

- New patient rights will be introduced, extending to primary healthcare and digital services.

Implementation steps taken

References

Political agreement on health reform 2024: https://www.ism.dk/Media/638682281997250085/01-Aftale-om-sundhedsreform-2024_TILG.pdf

Government health structure commission report: https://www.ism.dk/temaer/sundhedsstrukturkommissionen

6.1.1. Centralization and modernization of hospital infrastructure

Following the major structural reform in 2007, which changed the administrative landscape of the public sector, an ongoing centralization and modernization of the hospital structure have occurred through major hospital reform (see Olejaz et al., 2012). Several smaller hospitals have been closed or converted into other types of health care facilities, the number of acute hospitals (which may include several locations) has been reduced from 40 in 2006 to 21 in 2022, and several building projects, including six new “super-hospitals”, have received funding through a quality fund of DKK 25 billion (€3.4 billion) (see sections 4.1.1 and 5.4.3). The first of the six new regional “super-hospitals” was opened in 2021 (Sundhedsministeriet, 2021). The last building project is projected to open in 2025 (Sundhedsministeriet, 2021).6.1.2. Economic incentives to support the transition to care outside of hospitals

Municipal co-funding of hospital admissions was introduced in 2007 to strengthen economic incentives to increase capacity in municipalities. The initial general co-funding was criticized for being too broad, as municipalities had limited influence. It was therefore decided in 2016 to place a cap on municipal payments and differentiate co-funding by age, aiming to provide more direct incentives to the most relevant groups for municipal interventions (Sundhedsministeriet, 2016).

A keen focus on activity and waiting times has led to a continuous increase in productivity from 2002 to 2019. Patient flows in hospitals have become more streamlined, particularly for cancer and cardiovascular diseases leading to improved outcomes. Meanwhile, the average length of stay is very short compared with many other European countries, and many treatments are now available in an outpatient setting. Quality indicators and patient satisfaction have remained relatively high (Christiansen & Vrangbæk, 2018).

Increased productivity was supported by economic incentives requiring annual activity increases of 2% before additional activity-based funding on top of the block grant scheme can be accessed. This scheme was seen as highly effective in reducing waiting lists. Yet, over time, criticism grew of potential negative side-effects and limited incentives to innovate processes. This led to an agreement between the government and the regions to abolish the requirement of the 2% increase in productivity and change the criteria for the additional funding to a so-called proximity financing (a pay-for-performance scheme). The new criteria include reductions in overall hospital activity, unnecessary readmissions, hospital activity for chronic care patients and a transition to digital care (see section 3.3). The idea is to encourage regions to negotiate agreements to shift activity to municipal and primary care and to accelerate digital care solutions (Danske Regioner, 2022).