-

26 September 2025 | Country Update

Increased staffing levels and continued funding for maternity care -

17 March 2025 | Country Update

Waiting times for hospital treatment are back to pre-COVID-19 levels -

23 May 2024 | Country Update

Restructuring of the specialist training in general medicine to improve general practitioner coverage -

23 May 2024 | Country Update

New rules to ensure better protection for healthcare personnel -

19 December 2023 | Policy Analysis

The Resilience Commission has presented its recommendations

4.2. Human resources

As a result of the 2022 political agreement “A Good Start in Life”, staffing levels at hospital maternity wards have increased significantly in recent years, giving healthcare professionals more time to ensure safety and care for mothers and newborns.

From 2021 to 2024, the total staffing increased from 3,200 to 3,603 full-time equivalents (FTEs), an increase of 403 FTEs. This includes 215 additional midwives, along with 94 more nurses and 36 extra social and healthcare assistants across maternity departments nationwide.

The latest agreement from 2024 also allocates approximately DKK 68 million (€9.1 million) annually from 2025 onwards to further strengthen maternity services.

Authors

References

Udviklingen er vendt: Nu er der markant mere personale på fødeafdelingerne | Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet

Ny fødselsaftale sikrer hjemmebesøg til alle fødende | Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet

References

[1] OECD (2021), Health at a Glance: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/19991312

The Resilience Commission was established in the summer of 2022. The political aim was for the commission to provide recommendations for addressing the fundamental challenges in the Danish healthcare system and the care for older people, ensuring trained and competent personnel throughout the country. The commission was asked to tackle the longer-term challenges, considering the increasing older population and the expectation of a rise in chronic diseases and mental health disorders.

The commission’s main task has been to propose initiatives that can ensure more personnel in the future while also ensuring that personnel have more time to focus on core tasks related to citizens and patients. Initiatives include improving the organization of education, facilitating a smoother transition from education to the workforce, strengthening connections to the workplace, and promoting a more flexible and interdisciplinary approach to tasks. The commission has also focused on initiatives such as prioritization, smarter task-solving, and better utilization of technologies. It is hoped that these will provide staff with more time and space to fulfil their core responsibilities.

The 20 recommendations that the Commission proposed were:

Stronger prioritization and smarter task solution

1. A National Prioritization Council should release resources for core tasks.

2. Reducing inappropriate treatment through stronger professional prioritization.

3. Prioritization should be strengthened through shared decision-making, differentiated offerings, and increased self-care.

4. Inefficient documentation should be reduced.

5. Competencies should be utilized across regions and sectors.

6. A common principle of “digital and technological first” should be introduced.

7. Better frameworks for the rapid implementation of documented labour-saving technology should be ensured.

8. Digital competencies and technological understanding should be strengthened.

Attractive workplaces and time for core tasks

9. Leadership should be prioritized, and leadership quality should be strengthened.

10. More people should work full-time.

11. Night shifts should be reduced and shared among more employees.

12. Positions and career paths should be anchored in patient- and citizen-centred work.

13. The potential of later retirement from the workforce should be realized.

14. Competencies from abroad should be better utilized through strengthened integration.

15. More and better introductory programs for newly graduated individuals.

Right competencies and professional flexibility

16. There should be more coherence and greater flexibility across healthcare education programs.

17. Postgraduate and continuing education programs should be reformed to align career paths with practical experience.

18. Professional silos should be broken down, and more individuals should contribute.

19. The connection between education and job should be strengthened to avoid practice and responsibility shocks.

20. More strategic and long-term management of the supply of healthcare education should be ensured.

Authors

4.2.1. Planning and registration of human resources

The Danish Patient Safety Authority is responsible for registering the 17 medical professional categories in Denmark wherever they completed their professional training. Moreover, the Danish Patient Safety Authority licenses independent practices to medical doctors, dentists or chiropractors and issues specialist registrations in the 39 medical specialties and the two dental specialties. The Danish Patient Safety Authority is also tasked with supervising authorized health professionals and handles cases of individual and organizational malpractice.

The Ministry of Health defines the postgraduate training programmes for medical specialties based on advice from the Danish Health Authority and the National Council for Postgraduate Education of Physicians. Through the three Secretariats for Medical Training (Sekretariat for Lægelig Videreuddannelse), the National Council is responsible for regional planning and coordination of physicians’ clinical training. The National Council advises on the number and type of specialties, the number of students admitted to postgraduate training programmes, the proportion of physicians training in each specialty, and the duration and content of postgraduate training. The Danish Health Authority is responsible for the administration and the quality of training for specialist doctors and dentists and specialist training for nurses.

National surveys show that up to half of nurses feel uneasy about having their full name appear in medical records. Further, nearly one-third fear that they or their families might be approached or harassed during their free time [1, 2].

To address these concerns, the government has proposed new rules to provide healthcare personnel with better opportunities to conceal their names in medical records and log information on platforms such as sundhed.dk, protecting them from patients and citizens who have harassed or threatened them. As a result, these specific patients will not be able to see the names of their healthcare personnel when accessing their personal health information about medications, vaccinations, or appointments [2].

The measure aims to offer better protection against violence, threats, and harassment of healthcare personnel. The proposed new rules, currently in public consultation, will mean that healthcare personnel’s names can be hidden for 90 days, with the possibility of an extension [2].

Authors

4.2.2. Trends in the health workforce

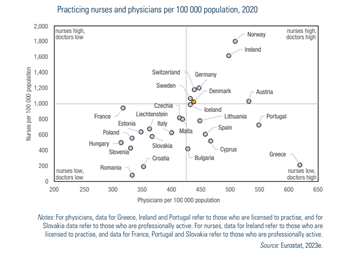

Despite having a relatively high number of practising doctors and nurses per capita in Europe (Fig4.2), Denmark has a general shortage of health professionals, particularly among nurses and nurse assistants (health and social care assistants). There are also shortages within some medical specialties, among others, in psychiatry, radiology and among GPs and especially outside the larger cities. Furthermore, it is estimated that 1.8 million Danes live in so-called medically underserved areas with too few GPs (lægedækningstruede områder) (PLO, 2019a).

Fig4.2

The current staffing challenges are found mainly in anaesthesia departments, intensive care units, internal medicine units and operating rooms, for which all regions have vacant positions. However, depending on the situation, department and region, the challenges look different and have different degrees of complexity. The coalition government from 2022 launched an emergency package for the health care system in February 2023 to address the immediate challenges with increasing waiting times and staff shortages. The package includes a grant of DKK 2 billion (€268.2 million) to strengthen the incentives for extra work at the hospitals in the next two years. The government will also collaborate with the regions to enable the use of other types of staff, including medical students, retired health care staff and administrative staff to ease the pressure on doctors and nurses (so-called task shifting). Another initiative is to streamline and thus shorten the authorization process for foreign health care personnel.

Tackling the longer-term challenges is the primary purpose of the Resilience Commission, which is to make continuous recommendations, starting in early 2023 and reporting their overall recommendations by the end of 2023. In a similar vein, due to the demographic changes in the population together with the shortage of staff issues, the newly appointed Health Structure Commission from March 2023 has been tasked to set up and elucidate the various models for the future organization of health care services by spring 2024. The models must support a preventive and coherent health care system with more equity, proximity and sustainability.

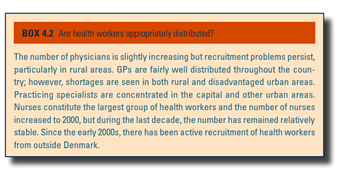

The shortage of GPs has been gradually developing over decades and has left more than 100 000 patients without a GP (see Box4.2). Those patients, however, have had access to either regionally run or private clinics. The shortage of GPs led to the formation of a ministerial working group (Lægedækningsudvalget) with broad involvement from employers and physicians’ organizations. The working group launched several initiatives to increase the number of GPs. The initiatives became part of a political plan with broad parliamentary support for better coverage of GPs (Sundhedsministeriet, 2017). The initiatives included, for example, training more GPs, changes in distribution for residency programmes, strengthened recruitment and retainment policies, increasingly flexible ways for GPs to run their practices, and financial incentives.

Box4.2

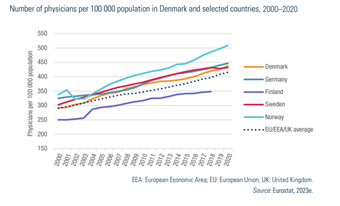

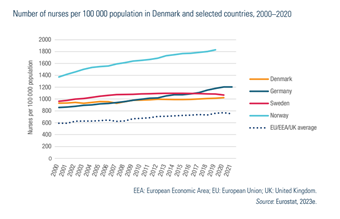

As seen across Europe, the number of doctors per 100 000 population has followed an upward trend. While it has been lower in Denmark than in other Nordic countries, it has been consistently above the EU average (Fig4.3). By contrast, while the number of nurses per 100 000 population has also been above the EU average, it has not increased at the same rate (Fig4.4). Over the last decade, it has remained relatively stable.

| Fig4.3 | Fig4.4 |

|  |

The average waiting times for hospital treatment increased during and after COVID-19, reaching 47 days in 2022 and 2023 [1].

As a response, the government and the interest organization for the regions, Danish Regions, agreed on an emergency plan (Akutplanen) in 2023 with several measures to increase capacity and reduce waiting times. The measures included financial incentives for specialized nurses and increasing enrollment in specialist training programs. Other measures focused on removing organizational bottlenecks and improving hospital capacity [2].

New data shows that the average waiting times for hospital treatment have decreased to 38 days at the end of 2024, reaching pre-COVID-19 levels [1].

Authors

4.2.3. Professional mobility of health workers

Because of the free movement of labour in the EU, many health professionals come to Denmark to work, and similarly Danish trained health professionals go abroad. Because of language barriers in the wider EU, most mobility of health professionals is within the Nordic countries where some languages are relatively similar. In 2019, there were approximately 2100 foreign trained doctors working in the Danish health system (Lægeforeningen, 2019).4.2.4. Training of health professionals

Admissions to medical schools have almost doubled over the last 20 years, bringing the total number at the four medical schools to 1395 places per year (Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2022a). In 2019, the production of medical graduates in Denmark was relatively high at 18.9 per 100 000 inhabitants against an overall OECD average of 13.2. The number was also higher in Denmark than in Norway (11.3) and similar to that in Sweden (13.5).4.2.5. Physicians’ career paths

Physicians’ career paths are based on a system of postgraduate medical education. Postgraduate medical education comprises pre-registration training, specialist and subspecialist training. The postgraduate medical education structure begins with pre-registration training called clinical basic education (klinisk basisuddannelse). The newly graduated medical doctors are placed in temporary positions for a year, made up of two six-month placements in a combination of internal medicine, surgery, psychiatry or general practice. The objective of clinical basic education is to give graduates a broad introduction to the health care sector. To distribute newly qualified doctors between specialties and geographical areas according to need and capacity, placements are distributed throughout the country by lottery.

Clinical basic education is followed by specialist training. Specialist training begins with a 12-month introduction as a prerequisite to applying for specialist training. The introduction to the specialty serves as a way of ensuring that the specialty is suitable for the candidate and that the candidate is right for the specialty. “Introduction” positions are opened according to agreements between the Danish Health Authority and the relevant specialty. The candidates are selected by an appointments committee comprising the department director/postgraduate clinical director and a representative of the Medical Association. Applicants are scored in seven categories, reflecting so-called doctors’ roles: medical expert, communicator, cooperator, health promoter, leader/administrator, academic and professional (Dehn et al., 2009).

This introduction is followed by specialization in one of 38 different medical specialties. Specialist training positions are a combination of placements in different departments for 48 to 60 months. Finally, specialization is completed at various locations, usually representing the specialty’s basic and highly specialized departments. This way, doctors in training are moved to different hospitals as part of their specialization.

4.2.6. Other health workers’ career paths

NURSES

Postgraduate nurse training is 30 to 78 weeks of on-the-job training. Completed postgraduate training confers the title of specialist nurse. Admission requirements for postgraduate training typically include at least two years of clinical practice as a nurse. Some specialties have additional specific requirements. The training has both theoretical and systematic clinical supervised units. At the time of writing, there are seven nurse specializations: mental health care for adults/children and adolescents, anaesthesiology, intensive care, infection hygiene, cancer care, health visiting and community health care. The Ministry of Health and the Danish Health Authority regulate postgraduate training.

The labour market for nurses is broad. There are good opportunities to work without on-call obligations, with greater flexibility and for a higher salary than a permanent position in the regional health service. Since 2019, there has been a large net departure of nurses from the regional hospitals to the municipal health sector as well as specialist practice and general practice. At the same time, there has been a smaller net departure to private hospitals and the industry of substitute workers.

MIDWIVES

Midwives in Denmark are mainly employed by obstetric departments in hospitals, including units in the hospital run by midwives (a midwifery unit/birth centre). Some midwives work in decentralized outpatient clinics or in GP practices.

PHARMACISTS

Most pharmacists work in private industry, typically in drug production, testing, registration or marketing. Others are employed in the food industry, environmental health or chemical production. A further proportion is publicly employed by universities in research and teaching or working with clinical pharmacy or production at one of the hospital pharmacies in the country. The rest typically work in retail pharmacies either as advisers for patients and doctors or as owners of the pharmacies.

DENTISTS

Dentists work in private practice or public dentistry. Public dentistry includes, among others, municipal dentistry, specialized hospital-based clinics, prison dentistry and clinics connected to universities. Other dentists work in teaching and research at universities and in the pharmaceutical industry.