-

16 September 2025 | Country Update

Mandatory electronic billing for outpatient services -

01 October 2021 | Country Update

Digital access to the patients’ medication plans -

01 January 2020 | Country Update

E-prescribing of pharmaceuticals becomes compulsory

4.1. Physical resources

4.1.1. Capital stock and investments

Current capital stock

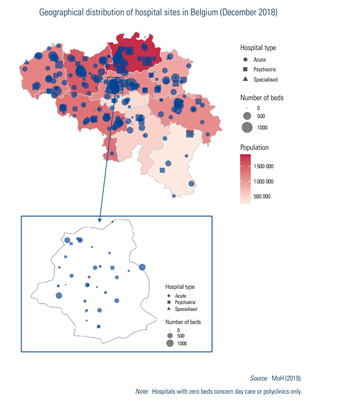

Key data on acute care hospitals can be consulted at www.healthybelgium.be/en/key-data-in-healthcare. The number of hospitals decreased from 521 in 1980 to 174 in 2018 (December 2018 data), mainly as a result of mergers rather than an actual decrease in the number of sites. Most hospitals have multiple sites on diverse locations (288 hospital sites in December 2018; see Box4.1 and Fig4.2).

Fig4.2

Among the 174 hospitals, 105 were acute care hospitals, 9 were specialized or geriatric hospitals and 60 were psychiatric hospitals. Geriatric hospitals are dedicated solely to older patients who need specialized care, whereas acute care hospitals also have a geriatrics department. Specialized hospitals concentrate on one or more health care specialties such as cardiopulmonary diseases, locomotor diseases and neurological disorders. Beyond the psychiatric hospitals, there are also psychogeriatric and neuropsychiatry care units in some acute hospitals (for short-stay treatment) (MoH, 2018d; Van de Voorde et al., 2014).

Acute hospitals include seven university hospitals. The university label does not necessarily mean that a university owns the hospital; however, at least three representatives of the university must be members of the university hospital’s governing body (BS-MB 10 August 2004).

Hospitals in Belgium are private non-profit-making (77.6%, 135/174 in 2018) or public (22.4%, 39/174 in 2018) institutions. Public hospitals are for the most part owned by a municipality, a province, a community or an inter-municipal association. Financing mechanisms as well as legislation are common to all hospitals, with the exception that, for public hospitals, internal management rules are more tightly defined and their deficits are covered, under certain conditions, by local authorities or inter-municipal associations (Justel 7 November 2008; BS-MB 5 August 1976). Medical centres labelled as private clinics are not considered hospitals according to legislation (see Section 5.4 on specialized care).

In 2005, the average age of hospitals was 26 years, but since then a construction calendar with priorities has been set up and investments have been made.

Regulation of capital investment

National planning has been established at the Federal level, defining programming criteria such as the number of beds per 100 000 inhabitants (see Section 2.4.2). Moreover, since 1982, the number of licensed beds for all general hospitals has been frozen. Any hospital construction, extension or reconversion has to fit into this national planning (for example the creation of new beds must be compensated by closing beds elsewhere, except in the case of shortfall of that type of bed).

In April 2015, the Minister of Social Affairs and Public Health launched a project to reform the hospital landscape, with a focus on capacity planning according to not only population needs but also scientific evidence (BS-MB 28 August 2017).

Investment funding

Hospitals receive financing from the government for capital investments but can also use their own resources or private loans; however, details about how hospital investments are financed are not transparent (Van de Voorde et al., 2014). From 2012 to 2017, investments in general hospitals remained at a high level, but were concentrated within a limited number of institutions (€1.5 billion of gross investments) (Belfius, 2018).

Due to the 6th State Reform, capital investment for hospital buildings, refurbishments, maintenance and heavy medical equipment are now the exclusive competence of the Federated entities (see Box4.2) but decisions have to fit with the national planning (Van de Voorde et al., 2014). A protocol agreement between the Federal State and Federated entities regulating investments during this transitional period was agreed (MoH, 2007).

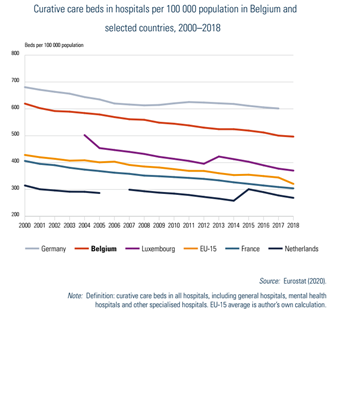

4.1.2. Infrastructure

The density of curative care beds decreased to 496.7 per 100 000 population in 2018. Compared with Belgium’s bordering countries, only Germany has a higher bed density (Fig4.1). A projection study on the required hospital capacity for 2025 concluded that there will be a decreased need for traditional hospital beds (−5.4%) especially maternity beds and surgical beds, but indicated a higher need for day hospitalization, geriatric beds and chronic care beds (Van de Voorde et al., 2017).

Fig4.1

4.1.3. Medical equipment

This section focuses on heavy medical equipment and services. Regulation of medical devices and aids can be found in Section 2.4.3.

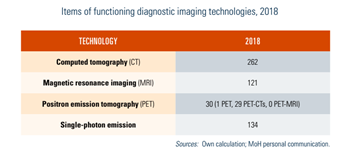

There are licensing criteria for the installation and running of heavy medical equipment (see Section 2.4.2) and since 2016, a national register has been established (BS-MB 3 February 2016). An operating licence granted by the Federal Agency for Nuclear Control is also required. Moreover, there is national planning to establish the maximum number of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scan devices (BS-MB 8 August 2014b; BS-MB 8 August 2014c; MoH, 2018b). Heavy medico-technical services such as medical imaging services with MRI or PET scan, radiotherapy services and dialysis centres are also subject to specific licensing criteria and national planning on number and distribution throughout the country (BS-MB 30 August 2000; Crommelynck, Degraeve & Lefèbvre, 2013).

The number of licensed heavy medical equipment is described in Table4.1. The geographical distribution can be found at https://www.health.belgium.be/fr/publications-imagerie-medicale.

Table4.1

Capital costs are financed by Federated entities (see Section 4.1.1), operational costs of medico-technical services are covered by the hospital budget and related physician fees are financed by the compulsory health insurance. Only activity on licensed equipment is reimbursed. Nevertheless, an audit revealed that there were reimbursement requests for examinations on non-licensed equipment. Since 2016, reimbursement requests must report the identification number of a correctly licensed device as well as the identification number of the licensed service (BS-MB 30 April 2014). Further follow-up of the number of examinations per equipment is expected (NIHDI, 2016a).

Compared with other European countries, Belgium has a higher use of medical imaging. However, some improvements on their appropriate use have been shown; for example, the use of medical imaging for the spine (computed tomography (CT), X-ray, MRI) has lowered by 2% per year (Devos et al., 2019). This may be a result of public health campaigns (since 2012) on the appropriate use of medical imaging in Belgium and other initiatives such as the setting up of the Belgian Medical Imaging Platform BELMIP (in 2010), a consultation platform between various authorities and stakeholders, including physicians. More recently, an inter-ministerial agreement on promoting appropriate practice, including the deployment of an evidence-based decision support system, an anti-fraud plan, greater accountability of prescribers and new methods of financing was concluded in 2018 (MoH, 2018b).

4.1.4. Information technology and eHealth

Since 2008, there has been an eHealth platform permitting the electronic exchange of secured data between health actors (BS-MB 13 October 2008). A national eHealth plan (2013–2018) was also launched, with the objectives to develop data exchanges between care providers, increase patient involvement and their knowledge related to eHealth, develop common terminology, simplify administrative procedures, improve effectiveness and create a transparent structure of governance with all involved actors (MoH, 2013). The new 2019–2021 eHealth plan will reinforce ongoing projects and strengthen coordination in eHealth initiatives (MoH, 2019b).

In 2018, most physicians had an Internet connection and were encouraged to digitize their medical information in electronic health records (EHRs), to upload a standardized medical summary (the SumEHR) in secure vaults and to keep this summary up to date. This allows health care professionals to access patient health data and to avoid the duplication of data by repeated examinations and procedures. Meanwhile, there are specific efforts towards training and ICT support of health care professionals (www.eenlijn.be; www.e-santewallonie.be; www.ehealthacademy.be).

In hospitals, a recurrent accelerator budget is agreed (BS-MB 13 June 2018) for the faster implementation of EHRs. At the beginning of 2019, 15% of general hospitals had EHRs and 75% used ePrescription (MoH, 2019b).

GPs also receive an extra lump sum when they are using approved software and make sufficient use of e-services. In 2016, 65% of the global medical records were electronic (Devos et al., 2019). With a view to a mandatory use from 1 January 2020, 26% of licensed physicians and 40% of dentists were prescribing electronically in May 2019 (Vertommen, 2019).

Recent e-services being developed relate to insurance data (for consulting insurance status, for requesting reimbursement of medication, for invoicing via Mycarenet), ePrescription of medicines and the use of real-time clinical guidelines during consultation (the Evidence Linker).

Since 2018, patients can access personal information about their health (both medical and administrative) and other general health-related information through an online portal (Personal Health Viewer: mijngezondheid.be; masante.belgique.be). There are also eHealth initiatives from the Federated entities.

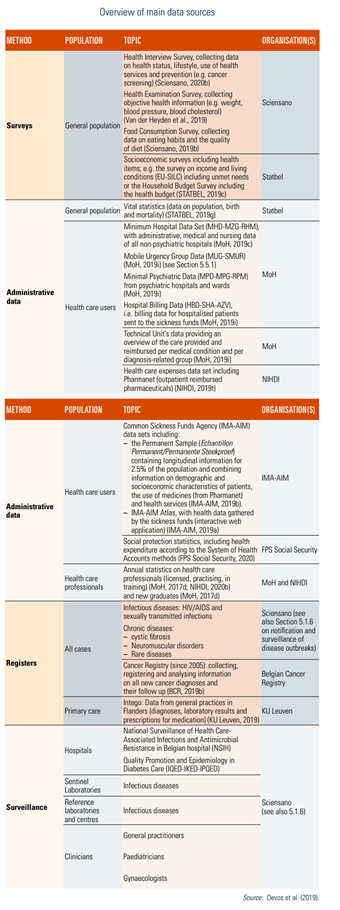

Health information systems

Belgium has made improvements in the field of health information, partially due to the efforts in eHealth, the regular assessment of the performance of the health system (see Chapter 7), the periodic health interview surveys, the collection of death certificate registration at national level, and the creation of Healthdata.be, an IT platform designed to centralize data for health research (Sciensano, 2019d). Yet, while a substantial amount of data is collected, important challenges remain (Devos et al., 2019). Some of the collected data are not used, and for other areas only limited data are available, for example, nursing, primary care, psychiatry, older people’s homes and nursing homes, and non-reimbursed payments. The lack of a Unique Patient Identifier between databases does not allow the tracking of readmissions or patient follow-ups in the health system after discharge. Additionally, coupling of data sources can take a lot of time, where linkage is carried out on an ad hoc basis rather than systematically.

An overview of the main databases according to the main actors involved is presented in Table2.2.[7] Data compilation at the national level may require cooperation with Federated entities.

Table2.2

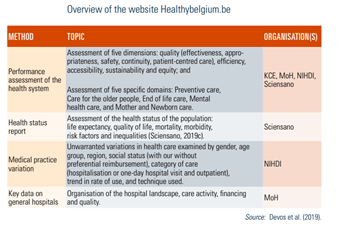

Moreover, since 2019, a new website, healthybelgium.be, brings together assessment reports on performance and other key data in health care (see Table2.3).

Table2.3

- 7. This list is not exhaustive. For a more detailed list of available databases related to infectious diseases see Van Goethem (2019). ↰

Authors

To improve the quality of pharmaceutical care, especially for patients with multiple medications, patients can now access a “medication plan” giving an overview of all their medicines via the Federal online platform Myhealth (masante.belgique.be). This digital tool allows patients to consult with their medication plan, to report feedback, e.g., on adverse events, and to share this information with all their health professionals, including emergency services in hospitals where necessary.

For more details see: https://www.inami.fgov.be/fr/themes/cout-remboursement/par-mutualite/medicament-produits-sante/Pages/schema-medication-apercu-medicaments-patient.aspx (French) / https://www.inami.fgov.be/nl/themas/kost-terugbetaling/door-ziekenfonds/geneesmiddel-gezondheidsproduct/Paginas/medicatieschema-overzicht-geneesmiddelen-patient.aspx (Dutch)

Authors

Towards improving the efficiency of the health system (i.e., facilitated administrative processes, reduced costs, and reduced risk of errors), electronic prescribing of outpatient pharmaceuticals became compulsory on 1 January 2020. The obligation to use electronic prescriptions for outpatients applies to physicians (general practitioners and specialists) as well as dentists and midwives, with an exemption for physicians aged 64 or over. Paper prescriptions are still allowed for home visits or visits to nursing homes and in cases of force majeure.

For more details see: https://www.inami.fgov.be/fr/themes/cout-remboursement/par-mutualite/medicament-produits-sante/prescrire-medicaments/Pages/prescrire-medicaments-electronique.aspx (French) / https://www.inami.fgov.be/nl/themas/kost-terugbetaling/door-ziekenfonds/geneesmiddel-gezondheidsproduct/geneesmiddel-voorschrijven/Paginas/geneesmiddelen-elektronisch-voorschrijven.aspx (Dutch)