Lene Korseberg and Ingrid Sperre Saunes

Introduction

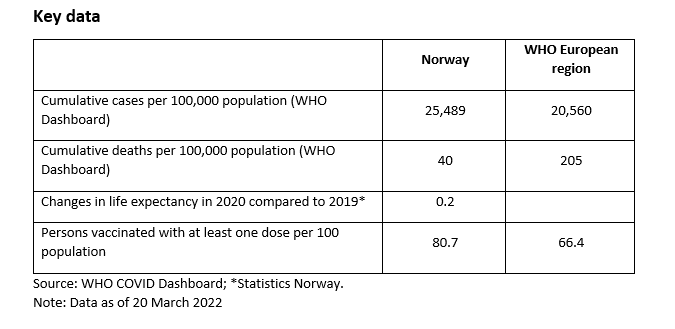

This snapshot explores the role of public health agencies and services in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway, using a sub-set of public health functions to serve as ‘tracers’ of how far public health was engaged in different aspects of the response to the pandemic. The report covers the role of public health agencies and services in the following areas: pandemic planning, overall governance of the pandemic response, guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions, communication, testing and tracing, and vaccination. It draws on the COVID-19 Health System Response Monitor (HSRM), various policy documents, academic and grey literature as well as completed/ongoing research projects.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) is the national institute for infectious disease control. Its responsibilities include monitoring, receiving notifications and reports, contact tracing, vaccine preparedness, advising, information and research. The NIPH is responsible for the notification system for communicable diseases, as well as the system for vaccine registration. It is also the national contact point for the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union (EU)/European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) as regards infectious disease control, as well as the secretariat for the Pandemic Committee.

Pandemic planning

Norway has a legal system of national preparedness based on the whole-of-governance approach (Health Preparedness Act 2000). This system includes the National Health Preparedness Plan (Regjeringen 2018), as well as the National Preparedness Plan for Outbreaks of Communicable Diseases (NPOCD 2019) and the National Preparedness Plan for Pandemic Influenza (Regjeringen 2014). These plans outline the roles and responsibilities of various agencies, entities and enterprises during a crisis situation.

The mandate of the NIPH is to provide assistance, advice, guidance and information to municipal and county authorities and to state institutions, health personnel and the population relating to communicable diseases and infectious disease control measures. The NIPH is also responsible for the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases (MSIS) and the National Reference Laboratory for pandemic diseases.

During a crisis, the Directorate of Health (DoH) is responsible for the national coordination of health system actions, as well as heading the National Health Preparedness Commission regarding biological threats (HPCB), which is an advisory body. The NIPH is represented in the HPCB and responsible for the secretariat-functions with regard to infection control. Beside this, the NIPH is expected to:

«contribute with monitoring, give advice on infection control measures and communication of risks, support the DoH and the Preparedness-Commission in developing and implementing communication strategies. Together with the DoH, NIPH’s role is thus to support and facilitate the activities of the preparedness commission and other relevant public bodies, and participate in the continuous preparedness with communication of information/advice.”

The role of the NIPH in pandemic response planning

The Ministry of Health and Care Services (MoH) delegated the responsibility to coordinate the health system’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak to the DoH in January 2020. The delegation of power facilitated the DoH’s decision to shut down the country from 12 March 2020. From 13 March 2020, the Ministry of Justice had the overall governance, while the MoH and the DoH were responsible for governance and coordination of health sector. Development and implementation of sector-specific regulations was transferred back to the ministries responsible for each sector in May 2020. The activities were coordinated with the NIPH and other relevant stakeholders, including the HPCB.

The NIPH had a discernible impact on pandemic response planning. It regularly published risk and response reports with strategic advice on handling the pandemic in the short- and long-term. The first such report was published on 28 January 2020. Since then, the report has been regularly updated and provides strategic advice on handling the pandemic until 2023. The aim is to have a dynamic response strategy to the pandemic, adjusted to its various stages in light of available knowledge. This has actively been used to adjust public health measures throughout the pandemic.

The NIPH has also established a pandemic preparedness registry, “Beredt C19”. The aim was to obtain the necessary knowledge about potential impacts of the COVID-19 epidemic, enabling the authorities to assess risks and implement measures to safeguard the health of the entire population. The register was established in close collaboration with the DoH, the Norwegian Intensive Care and Pandemic Registry and other data controllers for other data sources included in the register (FHI 2021a). The registry has contributed amongst others to identify vulnerable groups and to assess the effect of implemented COVID-19 measures.

The NIPH has established a live map of COVID-19 evidence. The purpose is to provide an overview of scientific publications on COVID-19, categorized and divided into more specific subgroups, providing quick access to specific topics of-relevant publications. As a result, the map also identifies research gaps, possibly guiding further research efforts (FHI 2021b). The NIPH is also a key stakeholder and advisory body, which, together with DoH, continuously updates and responds to governmental requests. The number of additional requests, besides those routinely mandated, from the Government to underlying agencies was 500 from January to July 2021.

In theory, the role of the NIPH did not change during the pandemic: it is still an advisory agency, tasked with providing assistance, advice, guidance and information to various stakeholders. This is supposed to be a complimentary role to that of the DoH, whose mandate it is to provide advice, implement policies that have been adopted, and administer regulations.

However, as pointed out by an evaluation carried out by the National COVID-Commission (NOU 2021: 6), the division of roles and labour between the NIPH and the DoH was somewhat unclear. At least in the early stages of the pandemic, it could look as if the NIPH was the infection control authority, rather than the DoH. At this point, there were also disagreements between the two agencies as to who should provide advice and information to the general population. It was necessary to establish a clearer division of labour and mutual understanding of the role of the two organizations, and this improved over time throughout the pandemic. This improvement was especially due to close discussions and cooperation between the two agencies.

Weaknesses of the pandemic response planning

The COVID-Commission report concluded that the overall governance of the COVID-pandemic has been good, largely due to high levels of compliance with national measures by the population. The report also stated that although the Government knew, from previous national risk assessments, that a pandemic was a most likely crisis, they were not sufficiently prepared for the outbreak of COVID-19. A scenario for a long-time duration of a pandemic was also not developed. Access to personal protective equipment and pharmaceuticals was seriously lacking, despite being previously reported as a problem. In distributing the equipment, the MoH paid insufficient attention to the needs of municipalities. The Government also failed to ensure that emergency measures did not infringe on personal liberties as stated in the Constitution or that individual rights according to the Human Rights declaration were safeguarded. The NIPH has, however, been credited with providing early warning of the pandemic in January 2020.

Factors explaining the relative successes and failures of the system

The system of emergency preparedness had been evaluated a short time before the start of the pandemic. This contributed to mostly updated preparedness plans, and an awareness of weak points, such as a lack of PPE and vulnerable access to pharmaceuticals. According to the National COVID-Commission, the municipalities have been instrumental in containing local outbreaks by means of testing, isolation, contact tracing and quarantine (whose initials in Norwegian form the acronym TISK), and by taking actions authorized by the national Act Relating to the Control of Communicable Diseases. NIPH has played an important role in assisting the municipalities with TISK guidance, training and advice. It has established a new emergency registry to ensure access to up-to-date information, relevant risk assessment and evaluation of public health measures.

In terms of failure, certain factors may be identified. First of all, even though the evaluation of emergency preparedness had warned about the lack of stockpiles for PPE, the country supplies covered only ordinary use for 14 days. In other words, this information did not lead to action before the pandemic was a fact. This also affected access to pharmaceuticals.

In the early phase of the pandemic, when the country closed down and international travel restrictions were implemented, a series of exemptions were made. Foreign workers traveling to and from Norway on a regular basis (shipping, oil and gas industry, health professionals amongst others) were supposed to have access, provided they adhered to specific quarantine regulations. Several local outbreaks were linked to inadequate living quarters, as well as lack of knowledge about and adherence to regulations. Systems for information exchange and follow-up of travellers were, at that point, not in place.

In the early stages of the pandemic it became clear that the public authorities struggled to reach all parts of the population with information regarding the pandemic and the implemented measures. In particular, this was the case for individuals and groups belonging to ethnic minorities, and people with disabilities, including those with hearing and visual impairments. To protect older people, isolation was enforced in nursing homes, as well as assisted living facilities. This imposed a heavy toll on older people. Additionally, the system of cancer screening was compromised. Screening services for breast-cancer in non-urban areas were suspended, and there was also scarcity in the performance of other cancer tests.

Planning: Lessons for the future

Three main lessons have been identified by the NIPH itself. First, although the public health agencies were well prepared for the initial parts of the pandemic, they were ill prepared organizationally for the enormous workload over time. The NIPH adapted its entire organizational structure, especially amongst the communication team, to better deal with the large and continuous information demand and changing circumstances.

Secondly, NIPH highlighted the need for a better and larger system for pre-empting requests for access to public documents and government information. Such requests were numerous throughout the pandemic, and at least initially there was not a workable system in place to meet such demands. Finally, from the beginning of the pandemic there was a need for more cross-sectoral cooperation relating to advice and measures, especially as concerns foreign travel and entry into Norway from abroad. The NIPH should, early on, have taken more initiative and insisted on cross-sectoral cooperation.

Overall governance of the pandemic response

On 31 January 2020, the MoH delegated the responsibility to coordinate the health system’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak to the DoH, with support from the NIPH as well as other relevant stakeholders in the HPCB. From 13 March 2020, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) led the overall response to COVID-19 through the Ministerial Crisis Council, whereas the DoH was responsible for coordination of the health system response through the Coordination Council. The MoJ took a more active role than that described in pandemic plans and arranged daily coordination meetings with the DoH, the NIPH and the Eastern Regional Health Authority, thereby indirectly leading the DoH coordination meetings. From 7 May 2020, the responsibility to develop and implement sector specific regulations has been transferred back to the ministries responsible for each sector. The DoH and the NIPH continue to support them by providing relevant information.

On 11 March 2020, the government also established a Covid-Commission (GCC) for weekly discussion on measures related to the pandemic. The GCC is an ad-hoc commission, established by the PM to enable rapid reactions and decisions related to the handling of the pandemic. The GCC consisted of the Prime Minister, the Ministers of Health and Care Services, Justice and Public Security, Foreign Affairs, Agriculture and Food, Trade and Industry and Finance, as well as leaders of the political parties represented in Government. Other heads of ministries or stakeholders were summoned as needed. GCC is a supplement to the ordinary government conferences, as well as the ministerial crisis council.

The role of the NIPH in the pandemic response

The 1994 Act Relating to the Control of Communicable Diseases describes the roles and responsibilities of administrative and public agencies in relation to the control of communicable diseases. The DoH has the overall responsibility for coordinating the responses within the health sector. This includes providing advice, guidelines, public communication, as well as resolutions to limit the spread and control of communicable diseases. As mentioned above, the mandate of the NIPH is to provide assistance, advice, guidance and information relating to communicable diseases and infectious disease control measures. When the DoH provides advice, they must gather scientific advice from the NIPH and decisions must be based on this knowledge. As such, the NIPH is the national institute for infectious disease control. It is an independent institution, which contributes with support and scientific guidance to the government, as well as other relevant agencies and stakeholders.

The role of the NIPH has slowly evolved over the last decade, and during the pandemic it became clear that not all of these changes were clearly incorporated into pandemic planning. The NIPH has been regularly represented in meetings at governmental, as well as ministerial level, a role not described in pandemic planning, but aligned with the agency’s role under normal conditions. The formal advice on policy measures from the NIPH was delivered through the DoH, which was responsible for coordinating the health system response. This differed from non-pandemic situations, where the NIPH gives their advice directly to the MoH/the government.

NIPH’s role has been to deliver the knowledge base whereupon decisions on policy measures for the pandemic response were taken. The NIPH has also contributed to shape the policy measures. As public health is a municipal responsibility, it is not governed by the ministries or other central health institutions. Municipalities must, however, confer with the NIPH and adhere to legislative measures when deciding how to handle the pandemic. All municipalities are free to instate stricter regulations than advised or mandated by central authorities.

Factors explaining the relative successes and failures of the response

In addition to adaptations and additional governance structures implemented during the crisis, facilitating more rapid decision-making, the existing welfare system is thought to have been an important factor. The system includes full sick pay, meaning that if people feel sick there are no disincentives to follow the advice and stay at home and quarantine if necessary. In addition to the ordinary safety net, the authorities have implemented economic measures to compensate companies and workers for loss of income due to the pandemic. The tri-partite organization between government, employer-organizations and unions has been important in the discussions of policy measures. Digitalization may also be a contributing factor, as about 50% of all employees worked remotely during the spring of 2020, thus avoiding public transport and person-to-person contact at offices etc.

Extreme measures were also taken to reduce mobility and interaction between people, especially during the early phase of the pandemic. This included closure of the border, ban on travelling to vacation homes, and isolation of older people living in nursing homes. The latter was not a nationally mandated regulation, but a highly encouraged and widely adopted measure. Criticism has been directed at the Norwegian authorities for breaching individual freedoms without due cause. In the early phases of the pandemic there is no documentation showing that the authorities discussed the wider impact of policy measures, beside limiting the spread of the pandemic.

Response: Lessons for the future

An important lesson is to ensure that crises management upholds the principles embedded in emergency preparedness plans and regular governance models, and ensuring that there are systems of governance that embrace all sectors. The government/MoH govern Regional Health Authorities and hospitals, and, as such, they are not subordinate to the DoH. Public health is governed by the municipalities and measures may, but are not required to be, coordinated by the counties. Municipalities are, however, not represented in any governing institution. The NIPH has an advisory role in measures to contain contagious diseases, and as such is an important link to the municipalities.

Guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions

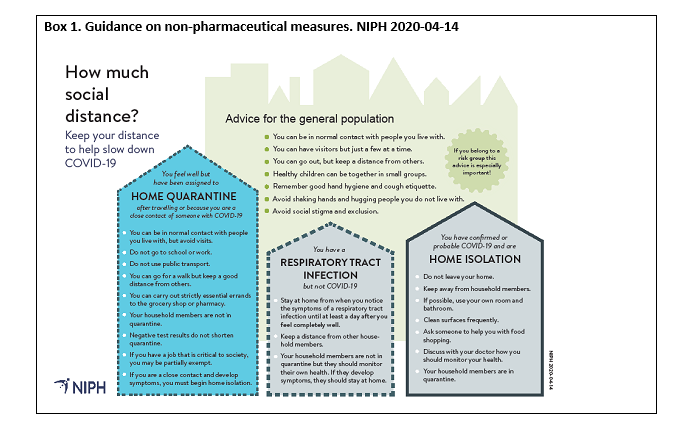

From the onset of the pandemic, it was clearly communicated to the public that non-pharmaceutical interventions – the use of masks, physical distancing and lockdowns – was the primary measure to curb infection. From late January 2020, communications from central health authorities emphasized the need for all to have proper coughing etiquette and good hand hygiene. By mid-February 2020, physical distancing and travel restrictions were first implemented and the NIPH was identified as the primary source on travel advice and preventive measures (Box 1). The lockdown, announced by the Government on 12 March 2020, was discussed with the NIPH and other stakeholders prior to its announcement. The decision was taken by the DoH, which three days previously was granted extraordinary powers from the government. The NIPH supported the decision on lockdown, even though they were less supportive of the closure of schools and kindergartens.

The NIPH has an independent role as advisory body to the public, municipalities, counties as well as central authorities. In the weeks before, as well as during the pandemic, the NIPH has been the primary deliverer of the knowledge base whereupon decisions were taken. This also includes advice to the general public on personal protection, as well as on how to best limit the spread of the virus. The recommendations from the NIPH are advisory only. However, through the HPCB, the NIPH delivers joint advice to the government on policy measures. To ensure that NIPH’s advice always reaches the decision-making forums in its original form, the NIPH requested that their analysis, as well as advice, on policy measures to the DoH/HPCB, would be forwarded to the DoH and the MOHCS/Government as appendixes to their joint recommendations.

The use of masks

When and where to use facemasks has been an ongoing public debate from the early phases of the pandemic. The NIPH has had a decisive role as they did not recommend the use of facemasks when the incidence rate in society was low. Instead, they emphasized physical distancing, and proper hand and cough hygiene. The authorities have neither recommended, nor advised against, the use of facemasks as a general precaution. A returning message has been that it is more important for people to continue to uphold physical distancing and hand hygiene.

The first specific mandate on facemasks was published on 10 June 2020, for national flights. The government later recommended municipalities with high incidence rates to mandate the use of facemasks in other situations where it was not possible to maintain physical distancing. Oslo municipality (the capital) first recommended the use of facemasks on public transport in August 2020, then mandated its use at the end of September 2020. In accordance with NIPH’s recommendations, facemasks have neither been recommended nor mandated for children under 12 years of age during the pandemic.

Social distancing

Social distancing and restrictions on travel have been central elements in the handling of the pandemic in Norway. The NIPH emphasized the need to keep attention on physical distance in all possible circumstances, as well as proper hand hygiene and coughing etiquette.

The early implementation of a lockdown included strict measures on physical distancing: indoors, people were advised to keep at least two metres distance, outside, the distance was limited to one metre and groups were advised not to be larger than five persons. When the process of reopening was planned, the NIPH advised to drop the limitation of gatherings to five persons in a group and have a joint rule of at least one metre distance indoors as well as outdoors. The government followed this advice and opened for larger gatherings in public, but kept the limit on private gatherings to groups of five. Even though NIPH’s advice was not followed in all respects, the advice seems to have had a somewhat sobering effect on the strict limitations introduced by politicians. The NIPH advised against the travel restriction to private holidays homes, as well as against the closure of childcare and educational facilities for children. These measures were lifted after four to six weeks.

The use of quarantine has been an area of discussion, where the NIPH has provided the knowledge base and advice, but where policy measures were often more restrictive. The NIPH supported the use of travel quarantine, as well as quarantine hotels. However, the latter was supported on a conditional basis. The NIPH argued that it should be needs-based and determined in the individual case (such as for non-residents), not as a collective measure for all non-essential travellers, something that it subsequently became (FHI 2020a).

Lockdown

Two weeks after the first case of COVID-19 in Norway had been identified, a national lockdown was announced and implemented on 12 March 2020. It closed most public life, banned all large events, and recommended social distancing and working from home. As announced by the Prime Minister, the decision introduced the most sweeping measures the country had seen during peacetime. The NIPH was involved in the discussion of policy measures, whereas the magnitude and timing were decided by the DoH, under close supervision of the MoH.

The national lockdown was accompanied by local restrictions in municipalities with local outbreaks. Several municipalities enforced stricter local quarantine regulations, despite the Government’s request to follow national regulations. The extent of the regulations differed amongst municipalities: in the northern parts of Norway some municipalities required quarantine for everybody visiting from the south, while others required quarantine for all non-residents. These decisions were not taken upon the advice of the NIPH.

Norway closed its borders to foreign residents in March 2020, first by issuing advice again all non-essential travel abroad. Then, on 17 March 2020, borders were closed for foreign nationals who did not have a residence permit to stay in Norway. Everybody arriving in the country had to test and quarantine. Exemptions were made for some seasonal workers from the European Economic Area (EEA) in late April 2020. Rules and regulations for border crossings were updated very frequently, making it difficult for people to plan and adhere to rules and regulations.

Overall, the impact of the NIPH on the guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions has been discernible. As an independent institution, the NIPH delivers independent scientific advice when asked. However, as the national authorities are framing the questions, limitations lie in the questions left out. The NIPH publishes weekly updates on the risk situation and recent/long term changes, as well as projections for the future. These are accompanied with in-depth analysis of known causes and what is less known. These reports have contributed to the sharing of the Covid-19 knowledge base, not only with the authorities and media, but also the population.

Factors explaining the relative successes and failures of the response

In terms of success, it is possible to identify the early communication of non-pharmaceutical interventions as the essential measure to limit the spread of the pandemic. It has been the overall message throughout this period. In terms of failure, the changing rules and regulations in connection with foreign travel have been central. This undermined the common-sense understanding linked to how to fight the pandemic with physical distancing. In particular, this was because the rules focussed on the causes for travelling, not the risk of exposure, when determining whether people needed to quarantine.

Communications strategy and communicating with the public

In the first phase of the pandemic in Norway, responsibility for the communications strategy and communicating with the public lay with the health authorities, i.e. the NIPH and the DoH. As part of their efforts to coordinate communication, they initially held daily meetings, under the auspices of the MoH, in which the respective communications directors participated.

From 11 March 2020, the Prime Minister's Office took the main responsibility for the communication strategy and communicating with the public. A number of measures were introduced to coordinate communication. One measure was to hold joint press conferences with the entire government apparatus and the health authorities. Other measures included creating inter-ministerial teams for the relevant government website and social media, and regular meetings by telephone between the heads of communications in the ministries and at the Prime Minister's office. In the early phase of the pandemic, all media communications related to the Corona pandemic were to be reported to and coordinated by the Prime Minister's Office.

The leading ministry at any given time also had a central coordinating role, as stated in the 2014 national contingency plan for pandemic influenza. Although the various ministries retain responsibility for communication within their sphere of responsibility, the leading ministry at the time is responsible for ensuring that coordinated information is provided to the media and the population, and that a comprehensive information strategy is formulated. The responsibility as lead ministry was transferred from the MoH to the MoJ on 13 March 2020, but the MoH still retained extensive responsibility for communication throughout the pandemic.

As the lead ministry, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security made a joint communication strategy for the ministries and agencies in May 2020. It stipulated the following goals for communication during the pandemic, set out in the report of the corona commission:

- Give hope and show the way through and out of the crisis. Create security, trust in the authorities and mobilize communities.

- Provide the population with knowledge and motivation for behaviours that reduce the spread of infection and at the same time limit the harmful effects on the economy, welfare and quality of life. The population is part of the solution.

- Create realistic expectations for the duration of the crisis, the extent, the degree of uncertainty and what costs it may cause for society and the individual.

- Crisis awareness in the population should be maintained for as long as necessary.

The role of the NIPH in the pandemic response

In light of these principles, the NIPH collaborated with the DoH on the preparation of a communication strategy at the beginning of the pandemic. This has been revised jointly several times and shared with other sectors and with the MoH. The division of labour previously described, with the role of the NIPH being to provide assistance, advice, guidance and information relating to diseases and infectious disease control measures, also applied to the communications strategy. They provided a continuous overview of the pandemic situation, advice on infection control, and recommended strategic measures.

Nevertheless, the division of labour between the various public health authorities with regard to the communication strategy was not without its challenges. As discussed above, the MoH had delegated the authority for pandemic coordination to the DoH. This was a new role and division of labour that had previously been described in emergency preparedness documents, but which had never been put into practice before the pandemic. There were thus several discussions, particularly between the NIPH and the DoH, as to what this coordination responsibility entailed, and which role remained for the NIPH. However, as time progressed, this improved, as the two agencies entered into discussions on various strategic communication issues, including where information about the various health services should be located, what kind of information should be located where, and how they should organize contact with the media. This improvement over time was also highlighted by the Corona Commission.

On 26 February 2020, when the first infection was confirmed in Norway, the NIPH held its first press conference on the Corona virus. The NIPH then invited to regular daily press conferences where their medical professionals could answer questions from journalists. The DoH held daily press conferences from 2 March 2020. On 11 March 2020, it was decided that the Prime Minister's Office should coordinate the communication work in the government apparatus. From the lockdown and eight weeks onwards, daily press conferences were held, first reduced to two-to-three times per week, then rarer.

The NIPH communications strategy has been based on three main principles, the first of which is openness. The NIPH has stressed the importance of being open and transparent about what they know and do not know at any given time, and to respond quickly with new and updated information when conditions change. The second principle has been availability vis-à-vis the media, and to allow those with expertise and knowledge on a given issue or situation address the public through the media. According to the NIPH, this has increased both the trustworthiness and the legitimacy of the information.

A third important principle has been to accommodate a productive dialogue, as opposed to one-sided communication, between the NIPH and society as a whole. This has taken place through social media, the information phone administrated by the DoH, incoming emails and other communication channels. Such feedback has given the NIPH input and views on advice and recommendations given throughout the pandemic, which in turn has been communicated to the DoH and the MoH, and was taken into consideration in future planning and communication. The NIPH is the agency that to the largest extent has communicated directly with the public throughout the pandemic. Although a large and time-consuming task, it has been important to build trust in the advice given, but also to allow the NIPH to adapt their communications strategy to better meet the needs and expectations of the public.

In terms of communication strategy, the input of the NIPH has to a large extent been relied upon. They have been able to take part and contribute to the development of the Corona communications strategy, in close collaboration with the DoH. The two agencies have joined in discussions about how to communicate information, and how to divide the tasks and responsibilities between them.

Factors explaining the relative successes and failures of the response

Overall, the NIPH communications strategy has been relatively successful. Two factors may be highlighted as contributing to its relative success.

First of all, the personnel in charge of communications were well prepared. They had prepared extensively in the weeks leading up to the beginning of the pandemic in Norway with regards to press releases, practicing press conferences, providing information to the population and the health service etc. The NIPH was not, however, sufficiently prepared for the lengthy duration of the emergency response organization and communication, and the extent of the need for information and dialogue with the population that arose in March 2020. The technical operating capacity on the health authority’s website was not sufficient to accommodate the influx of visitors – from approximately 10 million views in 2019, to approximately 100 million page views in 2020 - and was quickly transferred to a cloud service to mitigate this problem.

Secondly, as mentioned above, one of the fundamental principles of the NIPH communications strategy was openness and transparency and the NIPH believes that this approach to a large extent has contributed to their relative success, especially when it comes to building trust among the general population. However, during a crisis situation, there is also a need for the authorities to provide the public with uniform and consistent information, to avoid confusion and mixed or contradictory signals. These two principles are not always easy to reconcile and, when in conflict, the NIPH has tended to prioritise transparency over uniform information. This is because, despite the risks of confusion and mixed signals, they believe it has contributed to the high levels of trust currently experienced by the NIPH and other public authorities, as both the NIPH’s reputation survey and surveys from the DoH show.

At the same time, several factors have made the task of communicating effectively more difficult. First of all, it has been challenging to accommodate the need for quick and continuous information and recommendations with the NIPH’s responsibility to ensure that the information given is in fact based on sound medical advice. For example, the need to quickly inform about a new measure or advice meant that there was not always time to investigate and clarify the practical implications of such measures before they were implemented. This need for speed also meant that neither municipalities, nor the population at large, were well enough prepared to accommodate the recommendations and measures directed at them.

Another dilemma that became apparent was how to inform the public about the rate of infection in different parts of the immigrant and minority populations, while at the same time ensuring that such information would not have a stigmatizing effect. For the NIPH, it was vital to be transparent about the available information, in order for targeted measures to be applied to communities with a high level of infection. Close collaboration between local municipalities and those groups particularly affected by the pandemic was seen as crucial in this regard.

A third dilemma arose between proportionate infection control measures and the need for clear communication. On the one hand, it is easier to communicate a full closure or uniform measures across the country than it is to communicate differentiated infection control measures for different parts of the population or different parts of the country. On the other hand, although it would be easier to have strict measures that were easy to communicate, this is not in line with the Infection Control Act’s provisions that measures should not be more intrusive than necessary. It has been challenging to balance these conflicting requirements.

Communications: Lessons for the future

Although the communications strategy overall has been deemed to be effective, certain lessons may be drawn for the future. First of all, the rapid communication speed already mentioned may, in some circumstances, have led to confusion and mixed messages. However, the constant availability, both in the media and elsewhere, of medical professionals in the field, contributed positively to building and increasing knowledge and understanding of the advice given and measures implemented.

The health authorities lacked a specific plan for how to reach out to specific groups of the population. For example, being able to reach out and communicate effectively with the immigrant and minority population has been a challenge. From March 2020, information was prepared in more than 40 languages, but it was soon realised that this was not sufficient. An important tool has been to target the communication towards relevant groups, in close collaboration with the communities themselves. For example, responding to a high infection rate in the Somali community in Oslo in the spring of 2020, the community itself was vital in implementing measures that were crucial in reducing the infection. Another group that was difficult to reach through the traditional communication channels were those with hearing and visual impairments. The NIPH adapted their communication aimed at these groups in March 2020, for example through a collaboration with the Norwegian broadcasting house NRK to reach those with impaired hearing.

Finally, at the start of the pandemic, it became clear that the type of information expected from the general population exceeded that prepared by the health authorities. Generally, people asked for clear instruction as to what to do and how to behave, instead of receiving information on which to base their own decisions. In interviews, the NIPH expressed surprise at the level of detail the general population requested from the health authorities about what to do. The NIPH was not prepared, nor did it have the capacity, to provide information and advice to individuals, adapted to the individual’s situation.

Testing and tracing

Contact tracing has been used since the first case was reported on 26 February 2020. General practitioners (GPs) in the municipalities have, in cooperation with the NIPH (which can execute contact tracing for public transport), been responsible for tracing contacts for all patients with confirmed COVID-19 disease. In most cases, it was more practical for the Municipal Medical Officers to take over the responsibility for contact tracing from the GPs. In such cases, regular contact with the hospital serving their municipality ought to be maintained. For most of the pandemic, a person who has tested positive for COVID-19, the so-called index-person, had a duty to provide information on their close contacts, but they would not be prosecuted if they denied doing so. Until recently, close contacts also had a duty to get tested for COVID-19, but they would not be prosecuted if they decided not to. Throughout the pandemic, testing has been free of charge for the patient when it was requested for diagnostic purposes for according to regulations.

In hospitals, the physician in charge of infection control followed implemented procedures for the identification of patients who had been in contact with a confirmed case, near contacts and exposed health personnel. Data from Norwegian hospitals that are included in the intensive care registry feed into the Norwegian Intensive Care and Pandemic Registry and provide the basis for reports to the NIPH and the DoH, as part of COVID-19 monitoring in Norway. Such data may be used to keep track of critical care capacity.

As of 13 January 2022, contact tracing became a personal responsibility for those who test positive. Municipalities may thereby concentrate their efforts on contact-tracing within the health services and within vulnerable groups, such as care recipients and patients with increased risk. To ease the process of contact tracing everybody is advised to use a contact tracing app.

From 12 February 2022, testing is no longer recommended for close contacts and people at risk. Only those who have symptoms of COVID-19 are recommended to use a self-testing kit, and PCR-tests for confirmation of COVID-19 are no longer recommended. Furthermore, people are no longer requested to perform contact tracing. Isolation for people who test positive for COVID-19 is no longer required, but people are requested to stay at home for four days, and not return to work etc. until they have been free of symptoms for 24 hours.

The role of the NIPH in testing and tracing

Infectious disease surveillance is based on the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases (MSIS), hosted by the NIPH. The MSIS collects data about notifiable infectious diseases, as identified in the Disease Prevention Act, on cases submitted to the NIPH. The NIPH receives samples from cases of infectious diseases from the health authorities, and hosts the national reference laboratory. Norway has a network of clinical microbiology labs, mainly located at hospitals. The majority of these labs are responsible for both primary and specialist care in their area.

High capacity and rapid response on tests have been important not only for the patient, but also for those involved in contact-tracing, and for surveillance of the pandemic. The MSIS has gathered information on the individual case, symptoms, status, source of infection and location, and updates with information from lab-results. It is the physician’s responsibility (whether it is the GP, the hospital/institution etc.) to report cases to the MSIS and initiate contact-tracing. Reports to the MSIS were initially paper-based, which led to delays in reporting. From May 2020 an electronic reporting system was in place and most GPs could deliver the report immediately. Due to differences in reporting systems, the medical officer in the municipalities, responsible for follow-up on contact-tracing, was not integrated as part of the reporting system.

The NIPH also has field epidemiological teams to assists the municipal health and care services with evaluation, clarification and measures to stop infectious disease outbreaks. The NIPH’s responsibility in regard to contact-tracing includes guidelines, as well as advice to and close contact with municipalities and regions. The DoH is responsible for the planning and organizing of testing in municipalities. However, the NIPH has been in close contact with municipalities and regions throughout the pandemic. There have also been weekly meetings between the regional directors and the NIPH. This role did not change, as the NIPH produces national and local health reports on a regular basis, and delivers updated reports reflecting the ongoing pandemic.

The NIPH warned of the lack of sufficient testing capacity for a large-scale pandemic, and testing played a larger role in pandemic response than planned for. This led to the acquirement of extra test-machines, reagents which initially were a scarce resource, alongside PPE equipment and test-taking equipment. At the start of the pandemic, testing was strictly regulated due to the lack of capacity, as well as equipment. The latter was linked to challenges in production processes abroad.

Testing capacity for the COVID-19 virus increased significantly in the late spring of 2020. A new testing method was developed by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), in collaboration with St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim. The method uses nanoparticles to extract RNA from a solution containing a sample from the patient and compares it with the genetic code from the coronavirus sample. This test has been found to be more sensitive than commercial tests and contributed to an increase in testing capacity from about 30,000 a week to 300,000 tests per week. This corresponds to about 5% of the population.

The efficiency of the testing process, from test-taking, to getting results back to those who prescribed the test and the person tested, was challenging to improve, as this is not well described in the preparedness plans. Contact tracing is a responsibility of the municipalities, and the competence is local, as contact tracing is also relevant for other diseases. The scale of contact tracing, as with testing, went far beyond what had been anticipated.

The NIPH established a national contact-tracing team to support the municipalities, developed digital tools and managed the testing of them. A common set of digital tools, which would have been beneficial for collaboration and communication between the municipalities, has not been available. The Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) has, in collaboration with the WHO, the University of Oslo and the NIPH, adapted the DHIS2 COVID-19 Surveillance Package for use in Norway.

Testing and tracing: Lessons for the future

A mobile app for contact tracing developed by te NIPH was launched on 16 April 2020. By 18 April 2020, 1.2 million people (22% of the population) had downloaded the app. On 5 May 2020, the app had just below 750 000 active users. There have been concerns about privacy issues due to the use of GPS tracking, including from the Norwegian Data Protection Agency, and the number of active app users declined. The NIPH decided to halt the use of the contact tracing app and deleted all data collected. The mobile app for contact tracing developed for Denmark was further developed for the Norwegian market and launched by the end of 2020.

Corona virus modelling used by the NIPH for situational awareness and forecasting of the Corona virus outbreak in Norway was based on a stochastic SEIR-type model with a local transmission process in each municipality. It was applied in the period from March 2020 to the end of June 2020. At that point, a new model, a Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC model), was introduced and has been applied to estimate the parameters in the SEIR-model. The model allows for a daily variation in the reproduction number, and is based on a 7-days moving average. The spread between municipalities is modelled by following how people travel between municipalities. Information on travel between the different municipalities is based on mobile phone data.

Vaccination

Immunization in the national vaccination programme is voluntary and without co-payment in Norway. The COVID-19 vaccination was included in October 2020. The NIPH is responsible for the national vaccination programme, in collaboration with the municipalities, and was mandated by the Government to organize the necessary planning efforts to immunize the population against COVID-19, once one or more vaccines were approved. Due to limited availability, COVID vaccination was initially available only to priority groups, and subsequently rolled out according to the priority set in the vaccination strategy. As of 20 March 2022, 80.7% of the population had received at least one dose of vaccination.

The role of the NIPH in vaccination efforts

The government tasked the NIPH with developing a national plan for COVID vaccination. The plan included preparation, implementation and follow-up activities and was published in October 2020. The work was coordinated with the DoH, the Norwegian Medical Agency and Directorate for e-Health, and involved representatives from all stakeholders (municipalities, regions, GPs, hospitals etc) (FHI 2022a).

In November 2020, the NIPH published a report on ethical considerations for the vaccination strategy, followed by a recommendation on immunization strategies. These reports formed the basis of the Government’s decisions on the COVID vaccination programme. The goals were in line with WHO recommendations, to safeguard health, reduce disruptions in society and protect the economy (Regjeringen 2021).

National guidelines for COVID-19 vaccination were developed and published by the NIPH and have been available online since 7 December 2020 (FHI 2020b). The guidelines provide information on the overall strategy, the COVID-19 vaccination programme (FHI 2020c), information on the various roles and responsibilities for all stakeholders, distribution of vaccines, monitoring of vaccination, as well as reporting of adverse events. COVID-19 vaccinations are administered either by the municipalities (general population) or by the hospitals (health care workers). The guidelines are binding principles for the municipalities, which in turn are responsible for the distribution within their geographical area. Municipalities are free to decide on the organization of vaccination locally, including the partners they will involve. The NIPH has an advisory role in the development of local strategies.

The Government determined the vaccination aims and priority groups on the advice of the NIPH. Advice is given with regard to the overall aim of the COVID-vaccination programme, as well as targeted groups for vaccination. Older people, medical risk groups and healthcare professionals were initially given priority. Equal access to immunization was a vital part of the strategy, meaning that priority groups should have the same access in all municipalities. Adjustment to this principle were made in spring 2021, in order to obtain a more efficient strategy. Municipalities with a particular high incidence rate were given priority over municipalities with no or a low incidence rate in order to have a higher impact. This system was in place for a brief period when there still was a shortage of vaccines (FHI 2022b).

The NIPH recommended giving priority to healthcare professionals, advice initially not followed by the government. The decision was rapidly reversed, and health professionals were included from an early stage. The changes came after what seems to be a renewed emphasis from the NIPH, followed by a public debate (FHI 2020d; FHI 2020e; FHI 2021c). Based on the registration of adverse events in connection with the vaccines, the NIPH recommended first to pause, then to withdraw, the AstraZeneca and Janssen vaccines from the vaccination programme (FHI 2021d). Based on such recommendations, the government decided first to pause, then to remove, the vaccines from the programme.

Factors explaining the relative successes and failures of the vaccination efforts

The success relies heavily on a joint effort from all stakeholders, with frequent meetings. Weekly meetings were held between the regional directors (fylkesmenn), the DoH and the NIPH regarding immunization. At central level there were also weekly meetings regarding immunisation between the MoH, the NIPH, the DoH, the Norwegian Medicines Agency and the Norwegian Directorate of e-Health.

The Disease Prevention Act mandates the establishment of an emergency preparedness registry when needed. Based on this legislation the NIPH received the mandate to establish an emergency preparedness register for COVID-19 (Beredt C19) to ensure an ongoing overview and subsequent knowledge of the prevalence, causal relationships and consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic in Norway (FHI 2021a). The preparedness registry compiles information from established registries such as the vaccination registry, as well as other registries such as the Register of adverse events after vaccination reported by a healthcare professional (BIVAK) and the Adverse Events Register, which contains reports of suspected side effects of medicines reported from patients, relatives or health professionals.

Conclusion

The role of the NIPH in both pandemic planning, response and communication must be deemed an overall success. Due to a relatively up-to-date emergency response plan, the ability to adapt rapidly to changing circumstances, and an extensive system of monitoring – the Beredt C19 registry being central – the NIPH was able to provide knowledge-based advice to both the national authorities and the public at large throughout the Covid-19 pandemic in Norway.

Nevertheless, the transition from emergency plan to emergency response was challenging, especially given the long-term span of the pandemic. This was made more difficult by the unclear division of roles and responsibilities between the NIPH and the DoH at the beginning of the pandemic, and the challenging access to certain part of the population, including minorities and vulnerable groups. A fundamental challenge throughout this period has been to balance the need for a uniform and overarching response with the need to safeguard local autonomy and individual rights. The controversy surrounding the travel ban and entry restrictions is a good illustration of this, where the general, yet frequently changing, rules appeared to go against many people’s view of justice and common sense.

Such tensions between public health and individual rights have been present throughout the pandemic and the issue of proportionality, i.e. whether the response of the national authorities was in proportion to the risk at hand, is one that is still not resolved. This is an issue that ought to be addressed more explicitly in the time to come. This is especially the case as – with the benefit of hindsight now available – important lessons may here be drawn for the future, allowing the NIPH to be even more prepared if such an event as the Covid-19 pandemic were to happen again.

References

FHI (2020a). COVID-19 Oppdrag fra HOD nr. 208 om forberedelse av innstramminger 3. november 2020

FHI (2020b). Koronavaksinasjonsveilederen for kommuner og helseforetak. https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/koronavaksinasjonsveilederen-for-kommuner-og-helseforetak/

FHI (2020c). Coronavirus immunisation programme. https://www.fhi.no/en/id/vaccines/coronavirus-immunisation-programme/

FHI (2020d). Mulige kriterier for å prioritere mellom helsepersonellgrupper i primærhelsetjenesten. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/1af4c6e655014a738055c79b72396de8/mulige-kriterier-for-a-prioritere-mellom-helsepersonellgrupper-i-primarhelsetjenesten.pdf

FHI (2020e). Mulige kriterier for å prioritere mellom helsepersonellgrupper i spesialisthelsetjenesten. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/1af4c6e655014a738055c79b72396de8/mulige-kriterier-for-a-prioritere-mellom-helsepersonellgrupper-i-spesialisthelsetjenesten_.pdf

FHI (2021a). Emergency preparedness register for COVID-19 (Beredt C19). https://www.fhi.no/en/id/infectious-diseases/coronavirus/emergency-preparedness-register-for-covid-19/

FHI (2021b). Map of COVID-19 evidence. https://www.fhi.no/en/qk/systematic-reviews-hta/map/

FHI (2021c). Oppdrag 5 om forventede leveranser av vaksine og vurdering av nødvendige planforutsetninger. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/1af4c6e655014a738055c79b72396de8/oppdrag-5-om-forventede-leveranser-av-vaksine-og-vudering-av-nodvendige-planforutsetninger.pdf

FHI (2021d). Beslutningsnotat vedrørende pause i vaksinering med AstraZeneca-vaksinen. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/1af4c6e655014a738055c79b72396de8/vedlegg/notater-for-beslutninger-7.-mai-2020/21-03-25-beslutningsnotat-vedrorende-pause-i-vaksineringen-med-astrazeneca-vaksinen.pdf

FHI (2022a). Koronavaksinasjonsprogrammet - veileder for helsepersonell. https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/vaksinasjonsveilederen-for-helsepersonell/vaksinasjon/koronavaksinasjonsprogrammet/

FHI (2022b). Coronavirus vaccine - information for the public. https://www.fhi.no/en/id/vaccines/coronavirus-immunisation-programme/coronavirus-vaccine/

FHI (2023c). Definitions. https://www.fhi.no/en/op/novel-coronavirus-facts-advice/testing-and-follow-up/definitions-of-probable-and-confirmed-cases-of-coronavirus-covid-19-and-con/

Health Preparedness Act (2000). The Act of 23 June 2000 No. 56 on health and social preparedness (LOV-2000-06-23-56). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2000-06-23-56?q=helseberedskapsloven

Helse Bergen (2022). Norsk pandemiregister. https://helse-bergen.no/norsk-pandemiregister#om-norsk-pandemiregister

Koronakommisjonen (2021). Myndighetenes håndtering av koronapandemien. Rapport fra Koronakommisjonen, NOU 2021: 6. https://files.nettsteder.regjeringen.no/wpuploads01/blogs.dir/421/files/2021/04/Koronakommisjonens_rapport_NOU.pdf

Regjeringen (2014). Nasjonal beredskapsplan for pandemisk influensa. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c0e6b65e5edb4740bbdb89d67d4e9ad2/nasjonal_beredskapsplan_pandemisk_influensa_231014.pdf

Regjeringen (2018). Nasjonal helseberedskapsplan. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/a-verne-om-liv-og-helse/id2583172/

Regjeringen (2019). Nasjonal beredskapsplan mot utbrudd av alvorlige smittsomme sykdommer. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nasjonal-beredskapsplan-mot-utbrudd-av-alvorlige-smittsomme-sykdommer/id2680654/

Regjeringen (2021). Strategi og beredskapsplan for håndteringen av covid-19-pandemien. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/strategi-og-beredskapsplan-for-handteringen-av-covid-19-pandemien2/id2890210/