Ruth Waitzberg

Introduction, Objectives and Methods

This snapshot explores the role of public health agencies and services in responding to the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) in Israel, using a sub-set of public health functions to serve as ‘tracers’ of how far public health was engaged in different aspects of the response to the pandemic, covering the following areas: pandemic planning, overall governance of the pandemic response, guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions, communication, testing and tracing, and vaccination. It draws from the COVID-19 Health System Response Monitor (HSRM), various policy documents, academic and grey literature as well as completed or ongoing research projects. In addition, interviews with four key informants active in the field of public health were carried out. The interviewees occupy various positions and roles, and include epidemiologists, and public health physicians/officers, with membership of various advisory committees of the Israeli Ministries related to the COVID-19 response. This snapshot does not relate to further developments in the public health services response to the pandemic after its first year.

Background

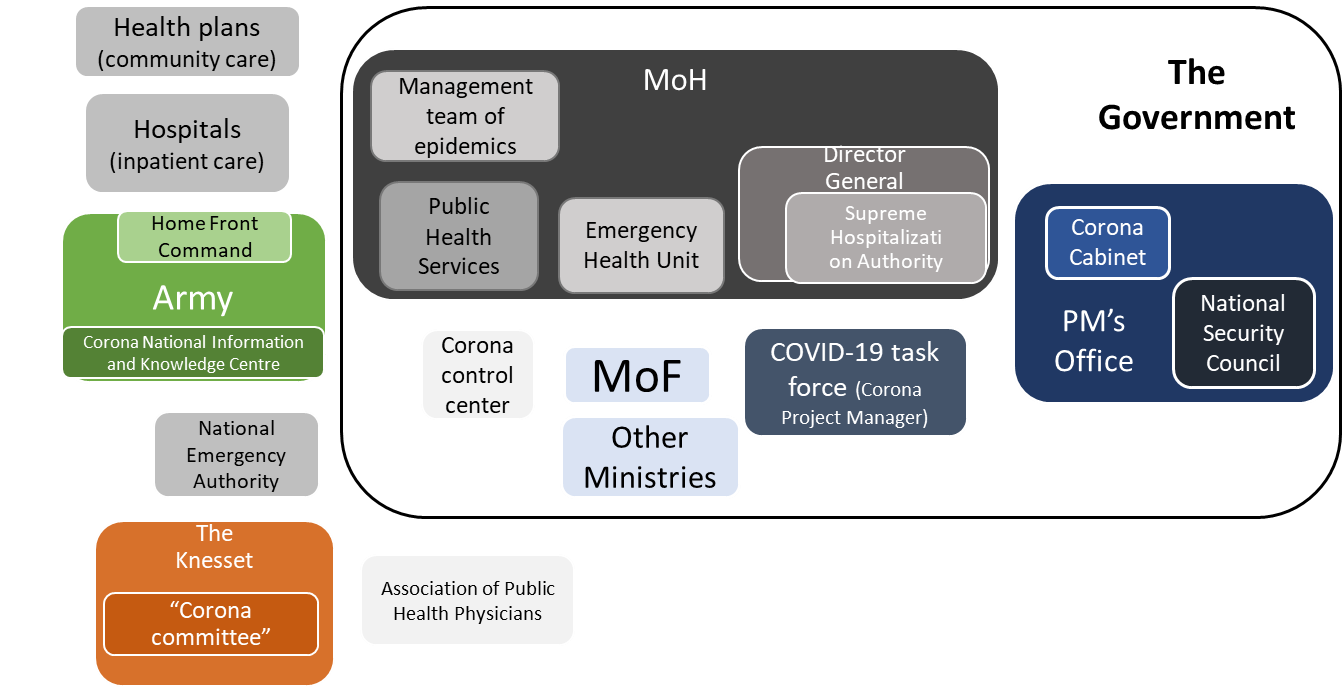

The Israeli Public Health Services Unit is a branch of the Ministry of Health (see Figure 1), which is directly responsible for the provision and funding of public health services (excluding curative care) through a budget that is separate from the National

Health Insurance budget (see box 1 for the statement of the public health services’ duties). The system of public health services is composed of the Public Health Headquarters unit, located at the Ministry of Health building in Jerusalem, and

seven District Health Bureaus that are located in the seven regions across the country. The system of public health services in Israel works closely with the military branch that deals with mass casualties.

Box 1: Public health services’ statement “Public health services deal with the healthy person in the area of personal, community and environmental preventive medicine while advancing actions of health promotion. The public health services are committed to promoting the health and prevention of diseases of the residents of the State of Israel, from the well-baby clinics, health services for school students, the district and district health bureaus to the professional administrative staff”. https://www.health.gov.il/unitsoffice/hd/ph/Pages/default.aspx |

The public health system has eroded over the past decades, in part because its budget has not increased in tandem with population growth, population ageing and other societal and technological changes. In addition, the outdated Public Health Act is a part of the 1940 Public Health Ordinance1, which dates back to the pre-Independence British Mandate.

The attrition of the public health budget has led to a corresponding erosion of the health workforce’s wages and status. It has also resulted in the dissolution of some speciality departments, and recruiting professionals for public health positions

has become increasingly difficult over time. Most public health experts come from the medical corps of the military, many of whom are physicians (rather than from academia or the medical track).

Preparedness and pandemic planning

Preparations for mass casualty situations, such as wars and nuclear, biological or chemical attacks, have been in place for decades, addressed primarily from a military perspective. Public health service units are also routinely prepared to respond to such scenarios. Planning, preparing for, and training in anticipation of these shocks have fostered collaborations between the military, the Ministry of Health and the main actors of the (curative) health system, such as health plans and hospitals. The collaboration has been strong particularly with hospitals, because treating injured or sick victims is a central part of the response to mass casualty situations. In particular, two units within the Ministry of Health primarily deal with shocks that require rapid mobilization of the health system. These are the “Management Team of Epidemics”, and the “Emergency Health Unit” (see Figure 1 for an illustration of these units). The latter is responsible for the “preparedness of health providers (hospitals, community clinics, ambulances, and emergency services) for absorption and treatment of conventional and unconventional casualties, in multi-casualty events in daily life and in times of war, while providing required medical care to the population”2. Neither of these units are part of the ‘Public Health Services’ within the Ministry of Health.

These two units have established good relations and routinely collaborate with the military and health care providers (including hospitals and health plans). Direct communication between army officers, Ministry of Health directors, directors of public health services, hospitals and health plans has contributed to the development of a body of knowledge, infrastructure, preparedness and training expertise for mass casualty events, including epidemics. Periodic collaborative exercises and training sessions conducted over the last 30 years, primarily for military purposes, facilitated the health system’s rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel. For example, there was prior experience of opening, expanding, and closing flexible/temporary wards for patients with COVID-19 and of converting medical wards into intensive care units; hospitals had pre-established communication channels to transfer patients when COVID-19 wards were full, and the digital infrastructure for reporting cases by severity, location and other parameters was easily adapted for the COVID-19 pandemic, as was organizational capacity for a mass vaccination rollout.

At the same time, existing plans and available knowledge were not always implemented or utilised in practice. For example, the Public Health Services Unit had created an epidemic preparedness plan based on modelling of influenza spread. The Ministry of Health circular 35/05 from 2005 specifies how Israel should prepare for a flu pandemic in line with WHO recommendations3. Nevertheless, it was not suitable for the COVID-19 pandemic because it assumed that vaccines would be promptly available, and it did not include non-pharmaceutical interventions such as quarantine, movement restrictions, and lockdowns. While the plan was suitable for epidemic control, preparing for a pandemic would have required another level of organization, such as collaboration with other countries. Israel had entered into dialogue with WHO and some countries regarding pandemic preparedness, but simulation exercises and implementation of the plan proved inadequate.

In addition, the public health agencies were not always involved in the response to the pandemic by the Ministry of Health or the government, inter alia because they were not intended or prepared to respond to global events such as pandemics. Moreover, other considerations beyond public health, such as economic needs, political interests, culture and acceptance of restrictions by the population, were equally important for the government.

Figure 1: Bodies and stakeholders involved in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020

Source: Author’s compilation

The role of public health agencies and services in the governance of the pandemic response

On 26 August 2020, the Ministry of Health established the ‘Corona Control Centre’ to concentrate and coordinate intra-ministerial responses to COVID-19. The public health agency that contributed most to the overall COVID-19 pandemic response was the Public Health Services’ Headquarters at the Ministry of Health, which coordinated surveillance, communication and reporting. The Director of Public Health Services and her team were also actively involved in guiding the pandemic response, although their professional recommendations were at times considered to be too inflexible and initially overlooked non-medical (e.g. socioeconomic) considerations. Regional public health bureaus continued to fulfil routine tasks such as disease prevention, well-baby clinics, environmental health, food and cosmetics control, but did not offer expert advice and were not involved in governance.

The Supreme Hospitalization Authority within the Ministry of Health, headed by the Director General of the Ministry, provides organizational and logistical infrastructure and is responsible for ensuring that the health system can adequately respond to emergencies. It comprises representatives of the Ministry of Health, the Israeli Defence Forces Medical Corps and the largest health plan in Israel (Clalit Health Services). (See Figure 1 for a visualization of the bodies involved in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic). The 2007 Pandemic Preparedness Programme assigns several roles to the Supreme Hospitalization Authority, including coordinating with government officials and the Ministry of Defence, administration, setting health policy, developing action plans and managing human resources. The Authority was intended to be central to the decision-making process in the event of a pandemic, but its involvement in the response to COVID-19 was not evident in official government information sources or the media. The roles of the Emergency Health Unit and of the Israel Centre for Disease Control (ICDC) within the Ministry of Health were also somewhat limited. Epidemiological data provided by the ICDC were directed towards new entities established to respond to the pandemic, rather than towards the system of public health services.

Meanwhile, the Association of Public Health Physicians actively counselled, guided, and influenced decision-makers during the pandemic. In addition, other public health experts outside of the Ministry of Health’s Public Health Services, including public health professionals and academics, were actively involved on media platforms, in various expert committees and supported decision-making with information and evidence. Additionally, the National Emergency Authority (NEA) coordinates and integrates all other organizations that manage national emergencies and mass casualty situations. The NEA routinely oversees emergency plans, instructs emergency bodies, conducts exercises and training, promotes international cooperation and coordinates emergency research and information. However, the division of responsibilities between the NEA, the Emergency Health Unit, and the Home Front Command is still unclear4. The COVID-19 pandemic was an event seen and referred to by certain authorities as an “emergency”, similar to a war or a biological attack. The addition of other entities to the governance of the pandemic response, such as the Ministry of Health, the public health services, the National Security Council and the COVID-19 Task Force (among others), contributed to the overlap and overall lack of clarity around responsibilities of the various organizations. In part, this was because some of these organizations considered the pandemic to be an emergency, whereas the system of public health services considered it to be a health emergency, the control of which they had gained experience for while responding to other epidemics and public health events such as Swine Flu in 2009, the detection of Polio virus in wastewater in 20135,6, and Measles outbreak in 20187–9. The Israeli Public Health Services usually leads the governance and execution of responses to these events, but during the COVID-19 pandemic they mainly provided data and advice, without leading the governance or the execution of the pandemic response. In reality, the COVID-19 pandemic was a major event that could not have been treated solely as a health emergency, since its impacts were felt well beyond the health system.

Governance of the COVID-19 response in practice

The management of COVID-19 evolved substantially since the initial outbreak in March 2020. Multiple stakeholders were involved, and it was not always clear where the limits of autonomy of each stakeholder lay. This might have resulted in some overlap of responsibilities.

On 27 January 2020, following reports of the SARS-CoV-2 virus spreading in China and Europe, the Ministry of Health signed a decree, in line with the Public Health Ordinance, to expand its powers to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. The Prime Minister and

the Director General of the Ministry of Health (who, for the first time, was not a health professional, as typical director generals are) led the initial national response to COVID-19 during the first and second wave

Despite having a robust preparedness plan in place for emergencies, the Israeli response to COVID-19 did not completely rely on the knowledge and institutional memory of public health services, in part because the knowledge, planning and training acquired was not always suitable for responding to a pandemic. In addition, the public health profession is not highly regarded in Israel, and public health professionals did not take the lead in the response, creating a vacuum that was immediately filled by other bodies, particularly the National Security Council and subsequently by the COVID-19 Task Force.

The main role of the National Security Council (NSC) is “to carry out quality staff work on a routine basis, to ensure that the state and the state bodies are prepared for emergency scenarios. During an emergency, it should conduct situation assessments, prepare and conduct discussions between the Prime Minister and the Cabinet”11. During the initial COVID-19 outbreak (February-May 2020), the Prime Minister decided that the NSC would not only advise, but would also become the executive body that supervises and coordinates responses to the pandemic across all relevant ministries and other bodies including the military and the secret service (the Mossad). The NSC opened an emergency management centre with representatives from each of the government ministries, divisions of the army, police, prison services and representatives from the national emergency service to centralize and optimize coordination. Since the NSC had no public health or epidemiological knowledge, it established six experts committees for advice. These were subsequently replaced by a ‘Joint Expert Committee’. In addition, the Intelligence Division of the Israeli Defence Forces established the Corona National Information and Knowledge Centre12 to assist the Ministry of Health with data and evidence on the spread of COVID-19 in Israel and around the world. With the development of the pandemic, some scientists acted as “knowledge integrators”, who brought to the government insights from academics who lack direct access to policy-makers.

The ‘Corona Cabinet’ is a government body that was assembled on 27 May 2020 as a forum of 16 ministers to better manage the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. On 26 July 2020, membership of the Corona Cabinet was reduced to 10 (male) government ministers that included the Prime Minister and the Ministers of Defence, Internal Security, Health, Finance, Foreign Affairs, Sciences and Technology, Justice, Economy and Industry and Interior. This body, led by the Prime Minister, operates in accordance with the new ‘Special Authorities to Combat the Novel Coronavirus’ (Temporary Provision) Law, 5780-2020 (the Coronavirus Law)13, which allows it to impose significant restrictions on public life. Each decision made by the Corona Cabinet is subject to parliamentary overview, and the parliament can vote to overturn such decisions seven days after the regulations are instituted. The Corona Cabinet coordinates all government agencies involved in dealing with COVID-19 to optimize government actions regarding health, as well as social and economic effects of the pandemic. Upon the establishment of the Corona Cabinet as an executive authority, the NSC returned to its original function as an advisory body.

In mid-July2020, the government appointed a ‘COVID-19 Task Force’ (Magen Israel) which took on responsibility for the overall governance of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of the tasks typically performed by public health

services were transferred to the COVID-19 Task Force, thereby bypassing the public health system and reducing its role in the response to the pandemic. The COVID-19 Task Force was responsible for setting short- and long-term health policies to tackle

the spread of COVID-19 in Israel. The Task Force reports directly to the Prime Minister and is led by a “Corona project manager”. When a new Director of public health services was appointed in January 2021, the Task Force and the public

health services restarted collaborating.

Communications strategy and communicating with the public

The Communications Unit within the Ministry of Health led communications with the Israeli public, following a communication strategy and in consultation with the public health services. A generous communications budget was made available to conduct market research and focus groups for this purpose. Within the COVID-19 Task Force, the ultra-Orthodox and Arab populations were represented in order to adapt the messages culturally to these populations14,15. However, this representation was set-up on an ad hoc basis and is not part of the usual set-up of public health agencies.

Communication with the public was successful, particularly during the first wave of the pandemic, when the Prime Minister would convey messages directly to the public, as well as during the vaccination campaign, when well-known physicians, hospital directors and other medical authorities conveyed key messages. Communication was tailored to target cultural minorities16 in addition to the general population. Messages at various levels of complexity were disseminated in 10 languages using diverse media and social media platforms through pamphlets, videos, infographics etc. They were culturally adapted to a variety of audiences, including the Ultra-Orthodox and Bedouin populations, despite their limited access to channels of information17. Public health agencies were not involved in the management of phone ‘hotlines’ established by the Ministry of Health and the health plans. The Ministry of Health also launched an automated online chat service designed to respond to the general public’s questions about COVID-19, yet, to our knowledge, public health agencies were again not part of the initiative. During the first wave, the Prime Minister, ministers and experts delivered briefings on an almost daily basis. As previously mentioned, public health professors and advisors were interviewed by mass media channels and became public figures, but the public health service system had limited role in this.

Testing and tracing

Tracing

The regional public health bureaus did not lead the pandemic response, but they were extensively engaged in epidemiological investigations during the first wave and invested significant efforts to keep up with tracing

as much as possible. Israel has a shortage of health workers in general, and of public health workers in particular. While crucial during the first wave, contact tracing was not carried out in the best manner, due to a lack of contact tracers and

epidemiological investigators. Although they were eventually supported by the military (i.e. the Home Front Command) the process took several months, which was not ideal.

Subsequently, the country invested heavily in the expansion of contact tracing capacity, including through involuntary tracing by the secret service, and the voluntary tracing application for mobile phones, which was an initiative of the Ministry of Health. Nevertheless, experts estimate that digital contact tracing did not add value or benefit to contact tracing efforts because it was implemented during a phase of the pandemic where the high number of infected people meant that public health experts could not trace and identify the origin of the spread.

Testing

Initially, Israel experienced a shortage of laboratories, and public health workers were involved in testing for COVID-19. Despite limited resources, manpower and poor infrastructure, public health laboratories performed well and were among the first to develop a testing kit for COVID-19.

During the first weeks of the pandemic, all tests were sent to one lab in the centre of the country. This bottleneck overloaded the laboratory and caused a delay in issuing results. As the pandemic progressed, more labs received certification and testing capacity increased significantly. During February and March 2020, only four labs were equipped with Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) instruments to perform COVID-19 tests. By mid-March 2020, the Ministry of Health was working to increase daily testing capacity by purchasing devices and training and equipping lab workers and laboratories. As testing capacity expanded, entities outside of the public health service, such as health plans, some hospitals and private laboratories adapted to perform the tests and increase screening capacity. As of 17 March 2020, there were 17 laboratories authorized by the Ministry of Health to perform SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) diagnosis. One and a half years later, approximately 50 laboratories were equipped for COVID-19 testing.

Vaccination efforts

The Ministry of Health sets vaccination policy. The Division of Epidemiology within the Ministry was responsible for writing the vaccine guidelines and establishing the prioritization policy and pace of vaccine roll-out. Regional public health bureaus did not have a major role in vaccination efforts. The entities operationally responsible for vaccine rollout were hospitals, health plans, and Israel's national emergency services (a non-governmental organization). Each entity was responsible for vaccinating a different population group, namely:

- General population: vaccinated by the four health plans

- Nursing home residents: vaccinated by Israel’s national emergency services organization

- Front-line health workers: vaccinated by hospitals and health plans paying them

The early success of Israel’s vaccination campaign entailed three major factors18:

(1) Vaccine availability: by January 2021, Israel had received more doses per capita than most other countries. This was in part due to an agreement between Pfizer and Israel “to determine whether herd immunity is achieved after reaching a certain percentage of vaccination coverage.”19 In addition, with the support of public health professionals, the Israeli MoH took the risk of procuring vaccines from various producers early on, prior to their approval.

(2) Sufficient logistical and workforce capacity to deliver doses to the population: The Ministry of Health, following the recommendations of its advisory boards, chose to rely on health plans’ strong primary care

structure

20 for vaccine rollout instead of the underfunded public health system. This decision was counterintuitive, since disease prevention and routine infant vaccinations fall under the direct responsibility of the public health system, and are

provided by Well-Baby clinics operated by the Ministry of Health (64%), municipalities (15.5%), and health plans (21%) 21. Although public health was one of the cornerstones of the health system, enjoyed the trust of the public22 and achieved high vaccination rates, it has been underfunded for years, leading to challenges in administering routine infant vaccinations

(3) Willing population: The Ministry of Health, together with the Israel Medical Association and several non-profit organizations that promote public health, launched exhaustive public health and awareness campaigns on social and mass media platforms to fight fake news and publicise images of well-known people getting the jab. These ranged from political and religious leaders to celebrities, in the hope that showcasing their vaccinations would increase population compliance and willingness to get vaccinated.

Other health system specific factors facilitated the rapid rollout of the vaccine. These include the organizational, technological and logistical capacities of Israel’s community-based health care providers; the availability of a cadre of well-trained,

salaried community-based nurses who are directly employed by those providers; a tradition of effective cooperation between government, health plans, hospitals, and emergency care providers (particularly during national emergencies); and tools and

decision-making frameworks to support vaccination campaigns. In addition, other factors were more specifically related to the COVID-19 vaccination effort, including the mobilization of special government funding for vaccine purchase and distribution;

timely contracting for a large supply of vaccines relative to Israel’s population; the use of simple, clear and easily implementable criteria for determining who had priority for receiving vaccines in the early phases; a creative technical response

that addressed the demanding requirements for cold storage of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, and tailored outreach efforts to encourage Israelis to register and get vaccinated

Conclusion

Israel deployed a dynamic response to the COVID-19 pandemic, adapting to changing needs as the pandemic evolved. This improvisation is typical of Israel25,26, and although at times it was perceived by the public as being inconsistent policy, it was a logical response to the situation.

Israel had substantial experience responding to public health events such as the Avian influenza (2006), Swine flu (2009), measles outbreak (2018-2019) and detection of polio virus in wastewater (2014), but not to pandemics. The Ministry of Health’s public health services, in particular, had extensive knowledge of and were highly prepared for epidemiological investigations, administration of vaccines, and sewage surveillance. However, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Ministry of Health’s General Director, supported by the Director of Public Health Services, took decisions without collaborating sufficiently with regional public health bureaus, the resulting policy was sometimes detached from local needs and probably stricter than necessary. In addition, due to the erosion of the public health services and the prestige of its professionals, some specialist experts in responding to emergencies and mass casualty situations were not involved in the governance of the initial phase of the response to COVID-19. This resulted in poor utilization of existing knowledge and experience in a time when the evolvement of the pandemic incurred many uncertainties. Lastly, inefficient policies arose from the lack of clarity and overlap of responsibilities and authority between the organizations that participated in the COVID-19 response.

In summary, the public health services were involved in counselling and providing data for the bodies that governed the response to the pandemic. However, addressing a pandemic requires responses from multiple stakeholders, most of which are out of scope of the public health services.

Limitations of the study

This study was not based on a systematic review of all policy documents related to the pandemic response, and it is possible that the method resulted in an investigator bias when presenting the findings. A great effort has been made to rely on as official

and varied documents as possible, in order to get a credible picture. I also interviewed a limited number of informants, who may also be biased. Nevertheless, the informants were carefully selected, according to their appropriate areas of knowledge

and expertise, and those who were not directly involved in responding to the pandemic to minimize their bias.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by the Israel Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization. The funders had no involvement in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report. The researcher is independent of the funder.

I thank Prof. Bruce Rosen and Dr. Michal Laron for the valuable comments on an earlier draft of this snapshot. I also thank the colleagues from The Smokler Center for Health Policy Research, Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute, for their comments on an earlier draft of this work.References

- Ministry of Environmental Protection. Public Health Ordinance. (1940).

- Ministry of Health. Emergency Division, Ministry of Health, Israel. https://www.health.gov.il/UnitsOffice/HD/emergency/Pages/default.aspx.

- Waitzberg, R. & Meshulam, A. COVID-19 Health System Response Monitor - Israel country page. https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/countries/israel/countrypage.aspx.

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A., Cohen, R. & Diamant, A. Experts’ Views on the Gaps in Public Health Emergency Preparedness in Israel: A Qualitative Case Study. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 15, 34–41 (2021).

- Brouwer, A. F. et al. Epidemiology of the silent polio outbreak in Rahat, Israel, based on modeling of environmental surveillance data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, E10625–E10633 (2018).

- Anis, E. et al. Insidious reintroduction of wild poliovirus into israel, 2013. Eurosurveillance 18, 20586 (2013).

- Salama, M. et al. A Measles Outbreak in the Tel Aviv District, Israel, 2018–2019. Clinical Infectious Diseases 72, 1649–1656 (2021).

- Stein-Zamir, C., Abramson, N. & Shoob, H. Notes from the Field: Large Measles Outbreak in Orthodox Jewish Communities — Jerusalem District, Israel, 2018–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, 562 (2020).

- Avramovich, E. et al. Measles Outbreak in a Highly Vaccinated Population — Israel, July–August 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67, 1186 (2018).

- Waitzberg, R. et al. Early health system responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Mediterranean countries: A tale of successes and challenges. Health Policy (2021) doi:10.1016/J.HEALTHPOL.2021.10.007.

- About the National Security Council. https://www.nsc.gov.il/English/About-the-Staff/Pages/default.aspx.

- Israeli Defense Force. Corona National Information and Knowledge Center. https://www.gov.il/he/departments/corona-national-information-and-knowledge-center/govil-landing-page (2020).

- מדינת ישראל. חוק סמכויות מיוחדות להתמודדות עם נגיף הקורונה החדש (הוראת שעה), תש"ף-2020. (2020).

- Rosen, B., Waitzberg, R. & Israeli, A. Israel’s rapid rollout of vaccinations for COVID-19. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 10, 6 (2021).

- Rosen, B., Waitzberg, R., Israeli, A., Hartal, M. & Davidovitch, N. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and access barriers to achieve persistent progress in Israel’s COVID-19 vaccination program. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 2021 10:1 10, 1–20 (2021).

- Waitzberg, R., Davidovitch, N., Leibner, G., Penn, N. & Brammli-Greenberg, S. Israel’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Tailoring measures for vulnerable cultural minority populations. International Journal for Equity in Health vol. 19 71 (2020).

- Waitzberg, R. & Eriksen, A. How have countries used communication strategies to increase the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Lessons from the first rollout in Denmark and Israel. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/monitors/hsrm/analyses (2022).

- Waitzberg, R. & Davidovitch, N. Israel’s vaccination rollout: short term success, but questions for the long run - The BMJ. BMJ Opinion (2021).

- REAL-WORLD EPIDEMIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE COLLABORATION AGREEMENT. Ministry of Health (2020).

- OECD. OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Israel 2012. (OECD, 2012). doi:10.1787/9789264029941-en.

- Zimmerman, D. R., Verbov, G., Edelstein, N. & Stein-Zamir, C. Preventive health services for young children in Israel: historical development and current challenges. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 2019 8:1 8, 1–8 (2019).

- Rubin, L. et al. Maternal and child health in Israel: building lives. The Lancet vol. 389 2514–2530 (2017).

- Stein-Zamir, C. & Israeli, A. Age-appropriate versus up-to-date coverage of routine childhood vaccinations among young children in Israel. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 13, 2102–2110 (2017).

- Stein-Zamir, C. & Israeli, A. Timeliness and completeness of routine childhood vaccinations in young children residing in a district with recurrent vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, Jerusalem, Israel. Eurosurveillance 24, 1800004 (2019).

- Galnoor, I. Public management in Israel: Development, structure, functions and reforms. Public Management in Israel: Development, Structure, Functions and Reforms 1–191 (2010) doi:10.4324/9780203844960.

- Sharkansky, I. & Zalmanovitch, Y. Improvisation in Public Administration and Policy Making in Israel. Public Administration Review 60, 321–329 (2000).