Jessica Walters, John Middleton

Introduction

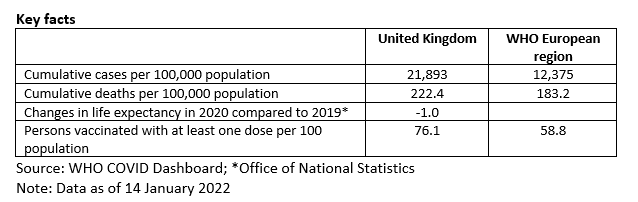

This snapshot explores the role of public health agencies and services in England in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. It uses a sub-set of public health functions to serve as ‘tracers’ of how far public health was engaged in different aspects of the response to the pandemic. The snapshot covers the role of public health agencies and services in the following areas: pandemic planning, overall governance of the pandemic response, guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions, communication, testing and tracing, and vaccination. The report draws on a review of published evidence, as well as expert interviews.

Pandemic planning

In as recent as October 2019 the United Kingdom (UK) was ranked second in the world in an overall Global Health Security Index score for epidemic or pandemic preparedness. Within this score was a first-place ranking for ‘Rapid response to and mitigation of the spread of an epidemic’, as well as a second-place ranking for ‘Commitments to improving national capacity, financing and adherence to norms’

Public Health England (PHE) was created by the UK coalition government in 2011 following the swine flu pandemic, with the purpose of the body being to ‘oversee national issues’, like pandemics

However, the overall role of PHE in response planning for COVID-19 was unclear. The lack of clarity on who was responsible for what was a huge hamper to the English systems response. PHE claimed that they had never been made responsible for pandemic planning. Subsequently, the initial response was faced with a lot of confusion, although it is now understood that PHE were not coordinating national level preparedness.

Three years prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, a cross-government test called ‘Exercise Cygnus’ was conducted that sought to test the UK government’s response to a simulated, serious influenza pandemic. The exercise exposed weaknesses in the system

The impact that PHE had on response planning for COVID-19 was therefore queried. In the first phase in January and February of 2020, there seemed to be a reasonable and proportionate response to the pandemic by PHE. They were responsible for sequencing the genomic testing before the pandemic and establishing the test for COVID-19 as it became known, as well as managing to track and trace in their own public health systems with their national, regional and local public health personnel tracking who had entered the country with the virus. Thus, they took a vital responsibility for ensuring that these people were quarantined.

Over the course of the pandemic, the response by PHE began to disintegrate, largely due to the sheer number of cases and the lack of an adequate testing facility. The system did not have the necessary chemicals and reagents required at that size. At the same time, responsibilities for response planning were being taken over by government bodies. The usual response to a pandemic via Cobra and civil contingences were not favoured. The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) was set up to give scientific advice, with a number of PHE members attending, although the interaction between this advice and final decisions were not public knowledge.

Failings in response planning also arose from the government’s hesitancy to implement initial public health measures and secure a lockdown. SAGE had modelling data that predicted the magnitude of deaths to come. The absence of mechanisms to deal with this scale of emergency meant that the country should have locked down earlier.

Overall, it is unclear what involvement PHE really had in response planning for the pandemic, and how much of their advice was considered by the government. When the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) was created in August 2020, questions arose on the politics and clarity at the time. The organisation was created to ensure a single leadership would be prepared to deal with future pandemics and other public health threats by bringing together PHE, NHS Test and Trace, and the Joint Biosecurity Centre (JBC)

Nevertheless, lessons can be drawn for future pandemic planning. It should be made clear who is responsible, with civil contingencies being made use of more frequently (or improved where necessary), and this could indeed be ensured by the new UKHSA. Enforcing pandemic planning and public health response under a single leadership may be imperative to a more successful outcome in future. Importantly, weaknesses exposed from a review of this pandemic should result in steps taken to address them, unlike in the case of swine flu and Exercise Cygnus. Improving PPE and testing capacity should be at the forefront. The reagents for testing must be accessible to procure when needed. With that being said, there is also a lesson in accepting that the next pandemic will be different, and that you cannot prepare for each disease the same.

Overall governance of the pandemic response – including the role of public health agencies in providing scientific guidance

PHE’s actual role in the overall governance of the response and providing scientific advice is again unclear.

When the COVID-19 outbreak began, the Coronavirus Act 2020 was implemented by the government which gave the UK’s devolved agencies and administrations greater powers within public health to coordinate the management of the pandemic

Scientific advice was led by the Chief Scientific Advisors, with a selected number of PHE representatives advising in SAGE. That being said, any scientific advice required effective translation into policy by those responsible, and this was not the role of PHE, since it was subordinated to the department and ministers. The lack of public health experts in SAGE meant SAGE would task PHE with a large volume of tasks that they did not have the resources for. Political advisors were attending SAGE meetings and this hugely undermined SAGE’s supposed role as an independent scientific advisory group

PHE’s role started strong in outbreak management with regard to testing, processing tests, track and trace, and significant scientific advisory (including on PPE). It should be noted that whilst they had an advisory role in PPE, the responsibility for PPE supply was with the NHS and the DHSC. Thus, the failings in procurement were not in the hands of PHE.

Throughout the pandemic, the deterioration of clarity on who was in charge and the rising infection rates meant PHE’s role faltered. Testing became rare unless patients were hospitalised. PHE were no longer responsible for testing as the government formed the ‘Test and Trace’ service, enlisting the private sector for help. However local and regional public health teams did still have some role in community contact tracing.

PHE’s overall role did not differ hugely from before the pandemic. To some, their apparent status may have changed, especially when compared to PHE’s previous crisis work in supporting the Ebola outbreak and the Salisbury Novichok poisoning

Lessons from these successes and failures of PHE’s governance of the pandemic have been learnt. SAGE should prohibit political advisors from attending meetings and engage with more public health experts instead

Guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions – in particular the use of masks, social distancing and lockdown

Guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions was unclear to the public from the start of the pandemic. Both the enforcement of lockdown and any guidance on masks were delayed. There was confusion around what the rules were, fuelled by poor messaging and frequent back-tracking by the government.

Lockdown was rejected by SAGE initially, with the idea of building a population herd immunity suggested. Modelling at the time was predicting deaths in the hundreds of thousands, if no public health measures such as closing schools or events were taken

However, PHE’s role in guiding non-pharmaceutical interventions was advisory rather than leading. The overall shaping of the response was from the DHSC, the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) office and ministers. The only exemption was that PHE was responsible for instructing on PPE to the NHS and social care. Any advice otherwise was recommendation only, rather than binding; in other words, they contributed but were not responsible for overall guidance. A particular success of PHE in this area was in evidence reviews, which were short, rapid reports by the COVID-19 Evidence Team that aimed to support the pandemic response. They sought to review and summarise available evidence and thus reveal evidence gaps in a multitude of intervention areas. Multiple successful reviews were published on the use and effectiveness of face coverings in healthcare settings, non-healthcare settings, community transmission, schools, social care, public transport, as well as investigating the efficacy of different types of face coverings/visors

There was no change to the legal authoritative role of PHE from before the pandemic. In fact, it turned out that an act of parliament was not even required to disestablish the organisation, as was done in August 2020 to create the UKHSA. Confusion persisted on what they had the power to do in the COVID-19 response and whether PHE could hold anyone accountable. Much of this was due to their commitment to availability for the government, rather than determining their own functions as an organisation.

Yet, public health professionals, if not specifically PHE, still managed to make a discernible impact. The directors of public health at the level of local authorities, the Faculty of Public Health, SAGE (specifically their public health representatives), scientists, epidemiologists, and NHS Digital, all had an influential role in shaping public health throughout the pandemic. The media and journals like the BMJ also played a key role in spreading messaging on non-pharmaceutical guidance. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) conducted community surveys on death and recovery rates, as well as positive tests, which contributed important data.

Drawing lessons in this area, the central role of clarity in planning and response emerges. This entails ensuring clarity in who is responsible for what and how much influence public health agencies can have over government decisions. There are huge lessons to be learnt for the government in listening to public health experts, importantly before advice is given to the public. Proper planning and coordination would help strengthen an understanding of the public on what needs to be done for their own safety, and also provide them with confidence that they are being kept safe by those in charge. Frequent back-tracking and mixed messaging only harmed adherence to future advice.

Communications strategy and communicating with the public

PHE worked closely with the DHSC in communications strategy and their communications were integrated with government communications. The Deputy CMO and PHE’s Deputy Medical Director, Dr Jenny Harries, was occasionally involved in the COVID-19 press briefings. Social marketing resources were used to get the messages across in wider areas, such as on advising the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) on what food should be delivered to people isolating.

A particular success of PHE’s communication was the UK Coronavirus Dashboard (https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk). This was developed by PHE and provides official data and statistics on the pandemic, updated daily. Transparency on actual figures has therefore been widely successful and appreciated by the media and the public, although it was not vocally messaged from PHE to the public. PHE also spent a lot of time briefing the media on the science, so that they could really understand what they were communicating to the public and cover the pandemic constructively.

However, despite significant contributions, PHE did not have a primary role of communicating to the public. The strategic approach was defined by the government, notably by the behavioural change experts that were brought in. Coordinating communication messages was also the responsibility of the government.

The messaging communicated by the government was often criticised for causing confusion. The ‘Stay Alert, Control The Virus, Save Lives’ updated slogan in May 2020 was lambasted by public relations experts and the public for being too vague and not providing practical advice that could be acted on

Conversely, local-level messaging from councils and local governments has been praised for its success. SAGE published a report from the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviours (SPI-B) in September 2020 that highlighted how public health messaging can be tailored to communities with different cultural backgrounds. This included tailoring messaging around cultural norms and high-risk events, such as Eid, as well as messaging in different languages

PHE’s role in communications differed from before the pandemic in that representatives were not among front runners in the media. During the Salisbury Novichok poisonings of 2018, the two front runners alongside the CMO were Dr Jenny Harries and Paul Cosford of PHE. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the briefings were mainly held by the Prime Minister, the Government Chief Scientific Advisor and the CMO. Hence, PHE’s role in communicating on camera was less pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reflecting on the area of communications, UKHSA should have a clear mandate going forward that allows them to have their own communications strategy, ensuring their expertise is always directly communicated to the public. Whilst their contributions were significant in what was communicated throughout COVID-19, PHE’s actual presence to the public was often invisible. The new Chief Executive of the UKHSA is in fact Dr Jenny Harries and her prior presence in briefings and acknowledgement by the media should be of vital use. It will also be important for her to understand clarity between the organisation’s role as a national agency and their role in advising government. Speaking out with clarity and publishing their own advice can still be done alongside their advising role, and can go in parallel to maintaining respect for government.

Testing and tracing

During the first stage of the pandemic up until March 2020, PHE were responsible for testing and tracing. They provided reference microbiology services and developed PCR tests that were rolled out to their labs. When transmission rates got high and cases began to get out of control the government passed on the responsibility to their newly formed ‘Test and Trace’ service. The service was responsible for the NHS app, mass testing, and contact tracing

PHE and local public health authorities, however, remained responsible for pillar 1 testing in England. This was the first pillar in a four-part route testing strategy outlined by the DHSC. It involved swab testing for those with clinical need, as well as health and social care workers, carried out in PHE labs

Pillar 1 maintained over 90% success rates in achieving an average test turnaround time of less that 24 hours, despite having significantly less funding than the privately run routes, and this has been highlighted as a success for PHE. Local public health teams already in place were tracing eight times more contacts than the national, privately funded service

Obvious failures arose from the government’s decision to stop PHE testing everyone and only test hospitalised patients during the first lockdown. This was detrimental to keeping up the response. PHE and NHS 111 became overwhelmed in their roles of contact tracing

Lessons can again be learnt in government policy. Bypassing local systems, or any type of public health coordinated national response

Vaccination efforts

PHE, along with the NHS, had a substantial and discernible impact on vaccination efforts in England.

The responsibility for advising the government on vaccination strategy, including recommendations on priority groups, lay with the independent Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI). However, there were some PHE members on the committee and PHE worked alongside them in developing an approach to implementing vaccination. PHE were involved in the distribution of vaccines and supporting NHS in their implementation, as well as in evaluating the effectiveness of vaccination. Mary Ramsay, the Head of Immunisation, Hepatitis and Blood Safety department at PHE, played a pivotal role in England’s vaccination strategy.

A significant success of PHE in vaccination efforts was the SIREN study. This was a study that followed ‘40,000 healthcare workers over a 12-month period to investigate COVID-19 reinfection rates and immune response’

PHE had no involvement in the legislative changes to rollout nor did their role differ from before the pandemic.

Vaccination rollout and uptake in England has generally been considered to be the most successful area of the COVID-19 pandemic response. It is itself a global success that three major vaccines were implemented in under a year, with England’s fast rollout exemplifying this. After the fast spread of the Omicron variant in December 2021, England’s booster programme was rapidly expanded. The government managed to offer every eligible adult a third vaccination before Christmas, and as of 19 January 2022, 81% of England’s eligible adults had been boosted

In regard to drawing lessons, it is important for the responsibility of PHE in vaccination to be recognised by government. Engaging with local public health authorities proved essential in addressing vaccine hesitancy, and a sense of understanding that engaging very locally is essential if you want to get implementation at the scale it was.

The response to COVID-19 is now a joint effort between the UKHSA, SAGE, and the CMO office, enforced by government policy. Successful vaccination rollout has offered a way out, but it is not the entire solution; it is important that some public health measures are maintained for the safety of England’s population, particularly those in socioeconomically deprived areas

Bibliography

aomrc, 2021. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges: The COVID-19 pandemic is not over and it will not be over on 19 July. [Online]

Available at: https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Covid_is_not_over_19_0721.pdf

Bird, S., 2020. The Salisbury Poisonings: a tale of public health and ordinary heroism. Journal of Public Health.

Campos-Matos, I. et al., 2021. Maximising benefit, reducing inequalities and ensuring deliverability: Prioritisation of COVID-19 vaccination in the UK. The Lancet, Volume 2.

Crozier, A., Mckee, M. & Rajan, S., 2020. Fixing England’s COVID-19 response: learning from international experience. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(11), pp. 422-427.

Department of Health, 2010. Healthy lives, healthy people: our strategy for public health in England, London: DH.

Department of Health, 2011. UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy, London: DH.

DHSC, 2020. GOV UK. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-creates-new-national-institute-for-health-protection

DHSC, 2020. GOV.UK: COVID-19 testing data: methodology note. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-testing-data-methodology/covid-19-testing-data-methodology-note

DHSC, 2020. GOV.UK: New chair of coronavirus ‘test and trace’ programme appointed. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-chair-of-coronavirus-test-and-trace-programme-appointed

DHSC, 2022. GOV.UK. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/england-to-return-to-plan-a-following-the-success-of-the-booster-programme

[Accessed 2022].

GHS, 2019. Building collective action and accountability, s.l.: John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, NTI and The Economist.

Greenhalgh, T., 2021. Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences: COVID: Seven reasons mask wearing in the west was unnecessarily delayed. [Online]

Available at: https://www.phc.ox.ac.uk/news/blog/covid-seven-reasons-mask-wearing-in-the-west-was-unnecessarily-delayed

Hickman, A., 2020. PR Week: PR pros lambast new Government 'Stay alert' slogan as 'unclear' and 'unhelpful'. [Online]

Available at: https://www.prweek.com/article/1682781/pr-pros-lambast-new-government-stay-alert-slogan-unclear-unhelpful

Hine, D., 2010. The 2009 Influenza Pandemic: An independent review of the UK response to the 2009 influenza pandemic, London: Cabinet Office.

House of Lords, 2020. UK Parliament. [Online]

Available at: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/uk-preparedness-for-covid-19-lords-scrutiny-of-the-2009-swine-flu-pandemic/

Lacobucci, G., 2020. Public Health England is axed in favour of new health protection agency. BMJ.

LGA, 2021. Local Government Association: Coronavirus (COVID-19) communications support and templates. [Online]

Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/guidance-and-resources/comms-hub-communications-support/coronavirus-covid-19

Mahase, E., 2020. Covid-19: Local health teams trace eight times more contacts than national service. BMJ.

Moll, R., Reece, S., Cosford, P. & Kessel, A., 2016. The Ebola epidemic and public health response. British Medical Bulletin, 117(1), pp. 15-23.

Paun, A., Shuttleworth, K., Nice, A. & Sargeant, J., 2020. Coronavirus and devolution, s.l.: Institute fo Government.

PHE, 2017. Exercise Cygnus Report: Tier One Command Post Exercise Pandemix Influenza 18 to 20 October, London: Public Health England.

PHE, 2020. Face coverings in the community and COVID-19: a rapid review. [Online]

Available at: https://phe.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-retrieve-file.pl?id=5f043ca658db1188ffae74827fa650d9

PHE, 2020. Factors associated with COVID-19 in care homes and domiciliary care, and effectiveness of interventions: a rapid review. [Online]

Available at: https://phe.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-retrieve-file.pl?id=1bc5eb8d6e5ef9a43c248ef08549ee53

PHE, 2020. Transmission of COVID-19 in school settings and interventions to reduce the transmission: a rapid review [Update 1]. [Online]

Available at: https://phe.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-retrieve-file.pl?id=6c419ea93fb3d57f71662fd2fd6be3f6

PHE, 2020. Transmission of COVID-19 on Public Transport: a rapid review. [Online]

Available at: https://phe.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-retrieve-file.pl?id=4f5a9a2ad2c495ff4e6312b2569869bc

PHE, 2021. Face coverings in the community and COVID-19: A rapid review (update 1), London: Public Health England.

Prime Minister's Office, 2021. GOV.UK. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-confirms-move-to-plan-b-in-england

[Accessed 2022].

Ramsay, M., 2021. GOV.UK: PHE: COVID-19: analysing first vaccine effectiveness in the UK. [Online]

Available at: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2021/02/23/covid-19-analysing-first-vaccine-effectiveness-in-the-uk/

Roderick, P., Macfarlane, A. & Pollock, A. M., 2020. Getting back on track: control of covid-19 outbreaks in the community. BMJ.

Scally, G., Jacobson, B. & Abbasi, K., 2020. The UK’s public health response to covid-19. The BMJ.

SPI-B, 2020. Public Health Messaging for Communities from Different Cultural Backgrounds. [Online]

Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/914924/s0649-public-health-messaging-bame-communities.pdf

Vize, R., 2020. Too slow and fundamentally flawed: why test and trace is a weak and inequitable defence against covid-19. BMJ.

Williams, G. A., Rejan, S. & Cylus, J. D., 2021. COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: How Austerity and a Loss of State Capacity Undermined the Crisis Response. In: S. L. Greer, E. J. King, E. Massard da Fonseca & A. Peralta-Santos, eds. Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, pp. 215-234.