Jean Macq

Introduction

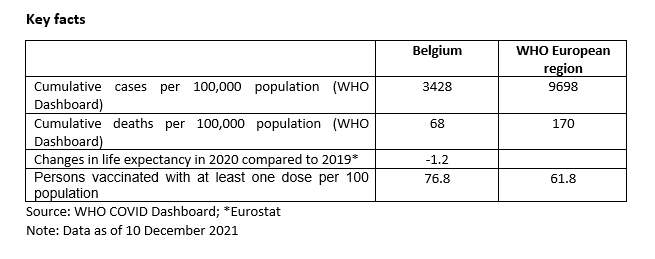

This snapshot explores the role of public health agencies and services in Belgium in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. It uses a sub-set of public health functions to serve as ‘tracers’ of how far public health was engaged in different aspects of the response to the pandemic. The snapshot covers the role of public health agencies and services in the following areas: pandemic planning, overall governance of the pandemic response, guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions, communication, testing and tracing, and vaccination. The report draws on a review of published evidence (including reports of the Parliamentary Commission), as well as expert interviews.

What are Belgium’s public health agencies?

Belgium is well known for its complex institutional organisation. This is also reflected in public health functions. For the sake of clarity (and to avoid lengthy explanations), this article focuses on Sciensano as the main public health agency (PHA) in Belgium. Indeed, although other agencies played a role as PHAs, Sciensano is the Belgian Health Research Institute(i). It implements policies in response to the legal framework and the priorities of the Federal Minister for Health and the President of the Federal Public Service (FPS) for Health, Food Chain Security and the Environment. [ii]

Sciensano is a scientific institution that aims to support all health authorities in making public health decisions. In this role, it plays a complementary role with other agencies, i.e. the Knowledge Centre on Health Care (KCE), the High Health Council (CSS), and the National Agency on Drugs (ANMS). It also interacts with the Federal Public Service (FPS) for Health, Food Chain Security and the Environment, as well as with the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (RIZIV), the Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid (Flemish Health Care Agency), the Joint Community Commission (Cocom), the German-speaking Community and the Agency for a Quality Life (AViQ). [iii]

Pandemic planning

In relation to pandemic planning, Sciensano intervened initially in surveillance and monitoring, in signal detection and epidemiologic intelligence. More concretely the epidemiological department of Sciensano provides, on a daily basis, support to the authorities in the decision-making process by offering, for example, an epidemiological description. It uses a number of surveillance networks for this purpose. A key aspect of epidemiologic description is signal detection. On the basis of all the data collected, it detects signals that are put into a module. This allows Sciensano to automatically monitor a whole series of indicators. The federated entities try to see if there is an explanation for the signal given, such as a cluster in a nursing home or school. The epidemiological department of Sciensano meets once a week to take stock of the signals they have been able to identify, the causes of the signals found, and to decide whether or not to send an alert to the mayor of the municipality concerned. In the event of an alert, the mayor is asked to mobilise the municipal crisis unit to assess the situation in the municipality.[iv] Sometimes a signal comes from abroad. It is then received by the national focal point, located in FPS for Health, Food Chain Security and the Environment. When the national focal point receives a signal from the WHO/ “Early Warning and Response System” (EC) they may transmit it directly to the health authorities at the federal or federated levels. [v]he perception of Sciensano from the outside and its role evolved during COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, (before the pandemic) Sciensano was largely unknown [vi] among healthcare professionals and the general population. This may be due a generally low profile of public health and due to divisions in competencies (between regions or communities and the federal level) and the “blur” that this brings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sciensano extended it data collection for surveillance as part of their role in surveillance and monitoring, in signal detection and epidemiological intelligence. The surveillance activities, started mainly with surveillance through compulsory declaration of infectious diseases, with the support of a network of laboratories, and the National Reference Centre (for Coronavirus). Sciensano developed operational and clinical surveillance with hospitals, to describe the profile of hospitalised patients. They also set up surveillance in nursing homes and started specific mortality surveillance alongside the surveillance of "all cause" mortality that was already carried out. The surveillance network via general practitioners was also activated. Sciensano also developed other data collection channels, for example including data from pharmacies. They also set up data collection for absenteeism and waste water [vii] In this way, Sciensano created new indicators for surveillance. [viii]

This process is part of a whole monitoring and risk management system in epidemic control. This was put in place in 2007 as a result of international recommendations. The new WHO health regulations were introduced in 2005, while everything was being put in place in Belgium, and this was finalised in 2007. In 2008 an official memorandum of understanding was published.[ix] The system rests on two pillars: the Risk Assessment Group (RAG) and the Risk Management Group (RMG). The RAG analyses the risk for the population on the basis of epidemiological and scientific data. It uses a signal detection process to identify a potential crisis, based on the surveillance system and event monitoring [x]. The Risk Assessment Group is a body that is coordinated (chaired) by Sciensano. Sciensano also supports the output of the Risk Assessment Group by making an evaluation of the risk. The RAG includes permanent members and invited members. The permanent members are representatives of the public health administrations. There is a representative from each Community (Flemish, Germanic, and Francophone) and each Region (Flanders, Brussels and Wallonia). There is also a representative of the Federal Government and a representative of the Superior Council of Health (CSS). This is the core group. Depending on the topic being dealt with, one or other expert is invited to participate in these meetings. [xi] The RAG gives recommendations (based on risk assessment) to the RMG and it is Sciensano’s role in the RMG to convey these recommendations. The RMG relies on the advice of the RAG to decide what measures need to be taken to protect public health. The RMG is composed of representatives of the health authorities and is chaired by the Belgian National Focal Point. In the event of a serious crisis, the RMG meets regularly to manage all health-related aspects of the crisis. If the crisis requires coordination between different sectors and administrations (beyond health aspects), a crisis cell is set up at the crisis centre of the FPS Interior. [xii]

In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the capacity of hospitals and more specifically intensive care units to respond has been challenged. Therefore, the Hospital & Transport Surge Capacity Committee (HTSC) has been meeting since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis to ensure adequate and effective control measures for hospitals and patient transport capacity (including emergency plans). The HTSC reports to the Risk Management Group. It is coordinated by the Directorate General for Health Care of the Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment. The HTSC is made up of representatives of the various federal public health authorities, hospital federations, the Federal Hygiene Inspectorate, the Ministry of Defence, as well as scientific experts [xiii].

The inter-ministerial commission (IMC) and COFECO (see below) were other important stakeholder in decision making during the COVID-19 pandemic. These structures illustrate the limits of the role of Sciensano. Indeed, the RMG and then the ministers in the interministerial commission (IMC) did not always choose the solutions proposed by the RAG. It is the prerogative of decision-makers to make decisions on how to use the information that is provided to them. [xiv]

After decisions have been made, Sciensano contributes to their implementation by coordinating the revision of general guidelines, but also by providing specific information on, for example, where a disease should be reported, to VAZG, AViQ or Cocom, depending on the specific details that need to be included. [xv]

To play its role, Sciensano needs to link permanently with healthcare providers (to get data) and policy-makers (i.e. governments) (to inform them). There are also frequent collaborations with universities. [xvi]

Most of the surveillance done by healthcare professionals (in particular the reporting of diseases) is done on a voluntary basis, based on a network of sentinel surveillance sites.

Overall governance of the pandemic response – including the role of Sciensano in providing scientific guidance

Given the exceptional nature (and societal consequences) of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a clear shift from managing and controlling a pandemic (a public health problem managed with public health structures) to addressing a national security problem (addressed by a national security council with a newly created structure).

In early 2020, the National Security Council (NSC) and the National Crisis Centre (NCCN) were quickly put at the centre of decision-making. This was extended to include the Ministers-President of the Regions and Communities to overcome an initial disorganisation in initiatives taken at different levels (some regions closed nursing homes, while others did not; some mayors decided to ban people who had returned from regions at risk from going to public places and schools, etc.). From then on, NSC took all policy decisions for managing the crisis. It is in this context that all mandatory measures of physical distancing have been taken. The various interministerial, interdepartmental and interregional crisis units supported these decisions, coordinated by the Federal Coordination Committee.

Additional national bodies were launched at the level of the National Crisis Centre (NCCN): the "Evaluation Unit" (CELEVAL), the Federal Coordination Committee (COFECO), the “INFOCEL” and the COVID high commissioner. The role of the RMG changed and it became responsible for governing the crisis at the level of the health system and to translate and implement the decisions of COFECO at the level of the health system. The "Evaluation Unit" (CELEVAL) has been composed of representatives of Sciensano, a Scientific Committee on COVID-19 set up in January 2020, the High Health Council, the administrations in charge of health within the Regions and Communities, as well as the FPS Interior and Mobility; it was chaired by the FPS Public Health. The scientific committee on COVID-19 is composed of health experts, virologists, economists, psychologists, behavioural experts, communication experts, etc. CELEVAL advises the authorities in taking decisions to combat the pandemic.

COFECO is chaired by the NCCN and brings together the Chair of the RMG and representatives of the Prime Minister, the Federal Ministers for Home Affairs, Justice, Finance, Foreign Affairs, Public Health, Budget, Mobility, Defence, Employment and Labour, as well as the Ministers-President of the Regions and Communities. The following administrations are also represented: the FPSs Public Health, Mobility, Economy and Defence, as well as the regional crisis centres and the federal police. COFECO prepares and coordinates the implementation of the policy decisions of the NSC at the strategic level. Management of the medical aspects is specifically coordinated by the FPS Public Health (including hospital capacity, personal protective equipment, testing, etc.).

A Corona commissioner was appointed in November 2020. Their role is to coordinate policies on the Covid pandemic between federal and federated entities. The commissioner has been assisted by a coordination unit and can also call on external experts. The coordination unit must be multidisciplinary: in addition to specific scientific and communication skills, it must include at least expertise in mental health, knowledge of the various vulnerable groups, and expertise on disease prevention and health promotion. [xvii]

Given the significant impact of the pandemic on socio-economic life, several crisis units have been set up to operationalise crisis management: the Operational Unit coordinated by the NCCN is operating around the clock. It promotes the flow of information between the authorities, ensures the operationality of the crisis infrastructures, and alerts the crisis units if necessary.

The Socio-Economic Unit is chaired by the FPS Economy and is composed of representatives of the Ministers of Economy and Employment, Public Health and SMEs, as well as the FPS Economy, Employment and Labour, Mobility, Social Security and the FPS Social Integration. It analyses and gives advice on the socio-economic impact of measures.

The Information Unit is co-chaired by the FPS Public Health and the NCCN. It ensures the coordination of all local, regional, community and federal authorities to ensure the coherence of crisis communication strategies and actions. It gives strategic advice to the competent authorities based on the perceived information needs of the population.

The Legal Units ensure the drafting of legal texts and provide answers to the many legal questions that arise in the context of this complex crisis management.

The International Unit facilitates the flow of information between counterpart crisis authorities at European level.

The Integrated Police Task Force coordinates the actions of the police services.

Other units have been activated to implement decisions by answering a series of frequently asked questions, or to ensure the translation of published texts. On 19 March 2020, the Economic Risk Management Group (ERMG) was set up to manage the economic and macroeconomic risks associated with the spread of COVID-19 in Belgium. [xviii]

On 27 March 2020, in view of the exceptional circumstances the federal government was given special powers to respond to the emergency, without going through the usual legislative procedures. The scope of these special powers was limited to urgent provisions relating to public health, public order, social provisions, and the safeguarding of the economy and citizens. [xix]

In addition to this exceptional governing structure, different “tasks forces” were set up, including for data collection, testing and tracing, implementing vaccination, protective measures (masks), etc.

On 6 April 2020, a new expert group was established, the Group of Experts in charge of the Exit Strategy (GEES) to prepare for a gradual relaxation of restrictive measures. This group was composed of five scientists (virologists, epidemiologists, and a biostatistician), three economists (among whom was the Governor of the National Bank of Belgium), one jurist, and the Secretary General of the Federation of Social Services.

The Group of Experts in charge of the Exit Strategy (GEES) advised the National Security Council in defining Belgium's exit strategy from the lockdown. For this, the GEES relied on indicators such as the decrease in the number of daily hospitalisations and trends in deaths linked to the virus. Nevertheless, the authorities insisted that the virus is still present in Belgium and that the measures could be reversed at any time. The transition phase began on 4 May 2020.

On 11 May 2020, an advisory group for mental health was created to advise the GEES about the necessary measures to be taken with regard to the mental health of the population.

At the end of 2020, the GEES became the GEMS (group of experts in charge of the management strategy).

On 24 April 2020 an inter-federal Testing & Contact Tracing Committee was launched. It consisted of a group of experts and representatives of the concerned Ministries of Health (tracing being a competence of the federated entities). This Committee was responsible for the staffing of the call centre and the training of staff, in close contact with other experts and consultation groups, in particular the Interministerial Conference on Public Health.

Later in 2020, a vaccination task force was also created to coordinate the vaccination strategy.

If outbreaks occur in Belgium, local authorities have received more powers to take direct action since the end of July 2020. Since then, local authorities can take actions directly. While they cannot go against the legislation of federal and federated authorities, they can decide for example to be more restrictive in the case of outbreaks in their municipality without having to wait for approval. [xx] [xxi]

Sciensano has been represented in some of the new national governance mechanisms (COFECO, communication, the ad-hoc scientific committee, Celeval, the task force for testing, and the task force for contact tracing). However, it has remained in its overall role of assessing the situation and advising decision-makers. In support of that role, Sciensano has also been involved in various research projects, in collaboration with universities.

Guidance on non-pharmaceutical interventions – in particular the use of masks, social distancing and lockdown

As mentioned above, Sciensano had two key roles in the response to the pandemic: (1) to coordinate the RAG and to convey the opinion of that group to the RMG which is the body taking decisions for epidemic control, including on non-pharmaceutical interventions; (2) it is responsible for coordinating implementation of decisions taken by public authorities. These procedures can change at any time, given the evolution of scientific knowledge and changes in the pandemic. Sometimes, these procedures may also need adaptation to local conditions. [xxii]

That means that RAG did provide recommendations for non-pharmaceutical interventions, but these were not necessarily followed by the RMG and even less so by the COFECO.

For example, the RAG advises on wearing a mask to protect healthcare staff from a respiratory virus, but it would not specify the type of mask. That is the work of the High Health Council, which has the scientific knowledge to do so. Indeed, the High Health Council is the body that has to give advice on a number of subjects. It also has to make a state-of-the-art assessment on those topics based on the current literature and knowledge and gives general recommendations [xxiii]. Also related to the use of masks there were two major issues illustrating the role of Sciensano. These were related to the initial shortage because of the previous destruction of strategic stock (to reduce public spending) and the need to purchase new masks, followed by queries by federal authorities about the toxicity of masks. In both cases Sciensano had little influence on deciding or managing the issue. In the latter case the High Health Council made a recommendation concerning mask toxicity [xxiv].

Another example is the duration of quarantine for people tested positive for Covid-19. At a certain stage it was discussed whether to reduce this duration, but there was a lack of consensus within the RAG. A literature review was undertaken to see if there were any new elements that would allow to reduce the duration of the quarantine. The experts were pretty much in agreement that the 14 days could be reduced to 10 days. However, there was a debate between the 10-day scenario and the 7-day scenario. In addition to these different expert opinions, operational considerations played a role. The GPs pointed out that their workload was already were high. These operational considerations influenced the final decision. [xxv]

Concerning the crisis colour code and, at a certain stage, consequent decisions on lockdown, curfew, etc., the RAG assesses the different indicators (often provided by Sciensano) every week and makes a risk assessment for the country, as well as for the different regions and provinces, right down to the municipal level. This risk assessment is eventually used by the RMG, and thereafter the National Crisis Centre and the COFECO decide on actions at country or regional level. [xxvi]

Communications strategy and communicating with the public

Sciensano is used to communicate in the scientific and technical arenas. It uses continuous literature scan and review (given the permanent evolution of COVID but also of prevention and treatment) to adapt recommendations that are communicated to professionals for management of the disease.

This new knowledge has been translated into frequently asked questions for doctors, into responses to parliamentarians, but also into responses to all the requests for information from health professionals received by phone and for the media (press). [xxvii]

On the other hand, Sciensano did not communicate directly to the public during the pandemic. Instead, it is the Crisis Centre that was charged with communicating to the public and Sciensano supports it in this effort, such as through its reports, but also by seconding communication experts. [xxviii]

However, it has been recognized in Belgium that communication with the public has not been easy during the pandemic. Particularly, the current crisis has shown that not all groups are affected in the same way or are equally able to find accessible information. This has been particularly evident with regard to vaccination. In order to respond to this challenge, Sciensano asked universities to develop a more inclusive communication approach with regard to Covid-19 and possible future crises in Belgium. The specific objectives were to take account of linguistic and cultural diversity and to develop further visual language and translation tools. The scientists also recognised the important role of interest groups, civil society organisations and local service providers, and involved them in the development of communication guidelines. [xxix]

Testing and tracing

Sciensano was involved in designing the system used for contact tracing. [xxx]

As coordinating body of the RAG, they developed a series of recommendations to the RMG. Initially the issue was to manage the risk and testing patients returning from the highest risk areas, which gradually expanded. Then, because the national reference centre was overloaded, it was decided to decentralize the sample analysis (from the reference lab to other labs). This was followed by the need to ensure protection for the personnel involved in testing (with the sample collection done initially in hospitals, and then progressively extended when protection material became more available).

Sciensano made information available to healthcare staff and the general public on its website and the general Coronavirus website (managed by FPS): info-coronavirus.be. Initially, reporting of contact tracing was done daily (during the first 247 days), and since 14 March 2021 it has been done every other day. There are also reports for the public health authorities - one in Dutch and one in French - and another specific report for the core group of federal ministers. Furthermore, there is a “dashboard” – Epistat, with a series of indicators, including results of testing and tracing [xxxi].

Sciensano coordinated the preparation and writing of procedures for testing and tracing (around 50 different procedures for the different partners in the health sector, be it doctors, general practitioners, hospitals, laboratories, ambulance drivers, and this has extended to chiropodists and psychologists). All the procedures were developed, in part for some, by the professional associations themselves, and in collaboration with the authorities. [xxxii] Procedures had to be updated to take account of the evolution of the pandemic and the availability of tests, including the decision to use rapid tests [xxxiii]

The implementation of testing and contact-tracing has been the responsibility of the federated entities. Indeed, the decisions made at federal level (inter-ministry of health commission) were implemented by federated agencies, i.e. the Flemish Agency for Care and Health – Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid; AVIQ Agency for a Quality Life-Agence pour une vie de Qualité; Iriscare; Ostbelgienlive (see for example the role of AVIQ [xxxiv)

After the political decision to carry out the identification of contacts through a call centre under the coordination of the federated entities, Sciensano was asked to support the creation of a database within a framework that would guarantee data protection, in compliance with the modalities related to the General Data Protection Regulation. [xxxv]

Vaccination efforts

Sciensano also contributed to vaccination efforts.

As coordinating agency for the RAG, they recommend vaccination, following guidelines from the High Health Council. Although Sciensano is not making decisions about which vaccines should be used, if there is a vaccine that has been approved and for which there are recommendations from the high Health Council, Sciensano promotes that recommendation. [xxxvi] Also, as part of the RAG, Sciensano participated in making recommendations on priority groups for vaccination.

Vaccine supply was coordinated at the EU level, and managed by the RMG (chaired by FSP of health). The implementation of the vaccination has been the responsibility of the agencies of the federated entities. To coordinate implementation, a special task force was created. It is co-headed by a professional from KCE and a university professor. This taskforce is part of the Corona Commissioner. This task force has been responsible for identifying, allocating and supporting all actions necessary to achieve the goals of the immunisation strategy. Its mission has been solely one of coordination. It has been composed of scientists, representatives of the federal and state authorities, crisis managers and, where necessary, representatives of professional organisations and technical working groups. [xxxvii]

Further to its participation in the RAG, Sciensano has been actively involved in many aspects of the post-authorisation surveillance of COVID-19 vaccines, in support of the Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products. This included the monitoring of vaccine use and coverage, vaccine efficacy and safety; the assessment of vaccine acceptance and the conduct of opinion surveys; the monitoring of the quality of vaccines marketed by pharmaceutical companies; and the measure of the immune responses to COVID-19 vaccines. [xxxviii] [xxxix]

Lessons learned for public health agencies in the future

The COVID-19 crisis has shed light on the importance of having a functional and coordinated “system” or “network” of different actors (public health agencies -in our case Sciensano- is one of them). Each of them needs to have a clear role and these need to be part of a clear process. It is difficult to disentangle some of the lessons learned for the whole system for pandemic control from those that apply more specifically to the role of the public health agency. The first two lessons below relate to the whole system, which are then followed by more specific lessons in line with the core functions of Sciensano. These are partly overlapping with the lessons identified by Sciensano itself [xxxx]

The overarching aims of pandemic control

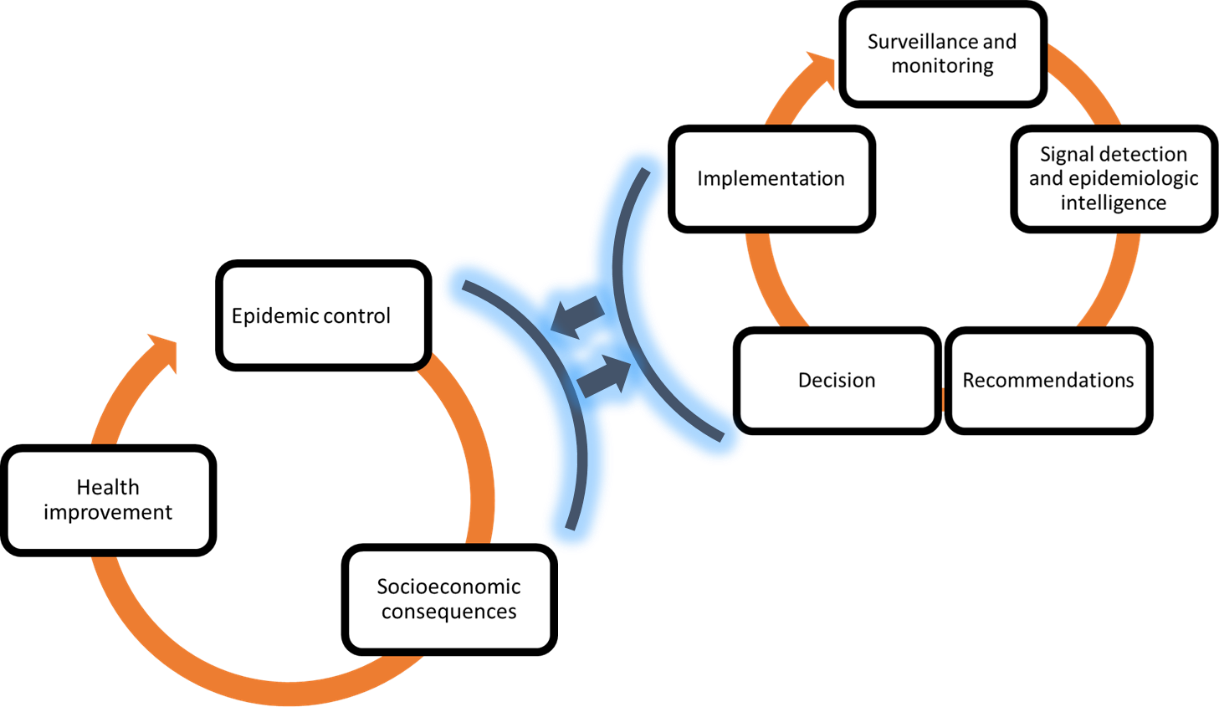

The evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the importance of broadening the overall perspective of pandemic control. Most of the lessons from the Belgian context can be related to the capacity to manage a double objective: controlling the pandemic and improving the overall health of the population. The view that it is vital to look at the control of the pandemic beyond the disease at stake (in this case COVID-19), has materialized in the creation of GEES and GEMS (with experts coming from a broad range of disciplines), in addition to the RAG, RMG and NSCC.

More concretely, before the COVID-19 crisis Sciensano (with other national and federated agencies) was clearly positioned to focus on the control of the pandemic. The epidemiological department of Sciensano was at the centre of a surveillance and monitoring system, had the capacity to detect signals and interpret them (through epidemiological intelligence), was able to provide recommendations leading to decisions (interventions to control the pandemic) and finally to implement them. This system was well in place before the COVID-19 crisis.

During the COVID-19 crisis, it quickly became apparent that the nature of decisions and the way they are implemented may contribute to controlling the pandemic, but will also have consequences for other societal areas, such as the socioeconomic situation (i.e. potentially leading to greater inequities). Indeed, lockdown, quarantine, but also diverging perceptions of vaccination can contribute to adverse socioeconomic events. It became also clear that it was important to combine the control of the pandemic with considerations of socioeconomic challenges, as both would have consequences for the overall health of the population. This is schematized in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The linkages between pandemic control and broader socioeconomic consequences

Source: Author’s compilation

It also became clear in the course of the COVID-19 crisis that responding to the pandemic needs coordination between a wide range of stakeholders, reflecting many different perspectives and priorities. This will have an impact on the role of public health agencies.

Clarifying roles and responsibilities

In order to achieve the double objective mentioned above, the role of the public health agency (Sciensano) was blurred by the creation of multiple groups, cells and taskforces. It would be helpful in the future to clarify the role of elected authorities, the role of civil servants (preexisting structures), the role of public health agencies, and the role of experts.

First, in Belgium several institutions/organizations have the role of formulating scientific public health recommendations. Although they complemented each other during the COVID-19 crisis, the relation between them came under scrutiny. Before the crisis, the Belgian Court of Audit (Rekenhof), advised to improve the coordination between various scientific advisory bodies, namely the High Health Council, the Federal Centre of Expertise (KCE), Sciensano (which then comprised two institutions), the Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products, the Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain (Afsca), the Federal Public Service, etc. During the crisis, the collaboration between KCE, Sciensano, the High Health Council and the Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products worked well. This brought many lessons to make future coordination more effective. [i]

Second, it was felt that a clear distribution of tasks and a clear command line with regard to the respective roles of PHAs, civil servants and “experts” was lacking. Namely, the many task forces and new expert commissions resulted in a lot of time being wasted on coordination and the need of communicating between various stakeholders at all levels.[ii] The question remains whether that was avoidable in such a context of uncertainty. As part of this issue, experts from Sciensano expressed that “the things that already exist work reasonably well and the things that do not yet exist have to be set up, which takes a lot of time and fine-tuning.” [iii] This has to do with the relation between structures and the ease of coordination. Also, it has to do with the training and competences of staff. Colleagues from Sciensano expressed that, in the existing structure, there are people “who are involved in crisis management on a daily basis as part of their profession”. This is seen to work well. Rather than creating new structures with experts not being used to crisis management, there is an argument for letting “existing structures function as they are”. [iv]

Third, as part of the division of roles between PHAs and civil servants, the division of competencies between federal (FPS for health) and federated [v]administrations was also an issue that requested a lot of coordination between Sciensano, FPS and federated administrations. Examples include the data collection to feed the monitoring system, the implementation of the vaccination strategy, and contact tracing and quarantine.

Investing in surveillance and monitoring and public services more generally

An extremely important aspect of a responsive system for pandemic control is the need for people dedicated to monitoring and signal detection. This is a rather invisible part of the system that shows its usefulness only in times of crisis, as became clear during the COVID-19 crisis. However, to make a functioning monitoring system possible, the surveillance and epidemiology department from Sciensano had to work 7/7 days and almost 24 hours a day. This demanded a strong commitment from staff because there were not sufficient to do this job, despite people from other departments coming to assist. One of the key reasons (beside “wastages” due to difficult coordination) is lack of investment in public health, [vi] with funding for public health agencies declining in the years prior to COVID-19. [vii]

Setting up new indicators

During the Covid-19 crisis new indicators were created (for example hospital utilization indicators). The whole process of collecting data, channeling it, constructing databases and eventually merging different databases, and feeding dashboards to visualize results had to be adapted to these new indicators. While this has been an opportunity to demonstrate the capacity of Sciensano, it also shed light on the difficulty to permanently adapt during the Covid-19 crisis. One of the most difficult aspects in adapting quickly is the “legal complexity”. As one expert from Sciensano mentioned: “Even in times of crisis, there is a whole series of rules and legal obligations that we have to follow. We are subject to the same rules as everyone else”. [viii]

Communicating with the public

The management of the COVID-19 crisis has been highly adaptive, because of the “volatility” of the situation. This means that, sometimes, changes in indicators or procedures were a source of confusion for health professionals or the general public. This confusion was sometimes made worse through contradictory interventions from multiple stakeholders (such as “experts” or politicians), leading to perceptions by the public that scientists have very different opinions and that recommendations are not underpinned by evidence. This led to a debate on what information and by whom should be communicated to the public. For example, by mid-2020, there was a debate on whether or not the opinions issued by the Group for Exit Strategy (GEES), the Risk Assessment Group (RAG), the Risk Management Group (RMG) and the Economic Risk Management Group (ERMG) should be publicized or not. [ix] Clear and transparent lines of communication would greatly enhance accountability and trust.

References

[i] Neve, Jean. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[ii]Neve, Jean. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[iii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[iv] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[v] the Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid (Flemish Health Care Agency), the Joint Community Commission (Cocom), the German-speaking Community or the Agency for a Quality Life (AViQ)

[vi] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[vii] Mentionner interview de C. Léonard

[viii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[i] See more info at https://www.sciensano.be/en/about-sciensano

[ii] EMCDC. “Belgian National Focal Point | Www.Emcdda.Europa.Eu.” https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/about/partners/reitox/belgium_en (August 23, 2021).

[iii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[iv] idem

[v] sciensano. 2020. “Place de Sciensano Dans Les Structures de Gestion de Crise de Santé Publique.” https://covid-19.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/Covid19/Sciensano_RAG structures gestion de crise.pdf (August 25, 2021).

[vi] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[vii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[viii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[ix] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[x] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xi] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xii] Gerkens, Sophie, and Karin Rondia. “COVID-19 Health System Responses - Belgium.” https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/countries/belgium/countrypage.aspx (June 1, 2020).

[xiii] https://consultativebodies.health.belgium.be/en/hospital-transport-surge-capacity-committee-htsc

[xiv] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xv] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xvi] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xvii] https://news.belgium.be/fr/composition-et-fonctionnement-de-la-cellule-de-coordination-du-commissaire-covid-19

[xviii] https://www.info-coronavirus.be/fr/que-font-les-autorites-sanitaires/

[xix] Gerkens, Sophie, and Karin Rondia. “COVID-19 Health System Responses - Belgium.” https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/countries/belgium/countrypage.aspx (June 1, 2020).

[xx] Gerkens, Sophie, and Karin Rondia. “COVID-19 Health System Responses - Belgium.” https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/countries/belgium/countrypage.aspx (June 1, 2020).

[xxi] https://www.info-coronavirus.be/fr/que-font-les-autorites-sanitaires/

[xxii] https://covid-19.sciensano.be/fr/procedures/home

[xxiii] Neve, Jean. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxv] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxvi] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxvii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxviii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxix] UCLouvain. 2021. “Covid : La Communication de Crise n’atteint Pas Tous Les Belges | UCLouvain.” https://uclouvain.be/fr/decouvrir/actualites/covid-la-communication-de-crise-n-atteint-pas-tous-les-belges.html (August 25, 2021).

[xxx] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxxi] https://datastudio.google.com/embed/u/0/reporting/c14a5cfc-cab7-4812-848c-0369173148ab/page/ZwmOB

[xxxii] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxxiii] See details on https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/countries/belgium/livinghit.aspx?Section=1.5%20Testing&Type=Section

[xxxiv] https://covid.aviq.be/fr/que-fait-laviq

[xxxv] https://covid-19.sciensano.be/fr/missions-de-sciensano

[xxxvi] Quoilin, Sophie. 2021. “Parliamentary Commission (from Belgian Federal Parliament) Audition.”

[xxxvii] https://www.health.belgium.be/de/node/38148

[xxxix] Gerkens, Sophie, and Karin Rondia. “COVID-19 Health System Responses - Belgium.” https://www.covid19healthsystem.org/countries/belgium/countrypage.aspx (June 1, 2020).

[xxxx] sciensano. “Rapport d’activités Sciensano 2020 | Sciensano.Be.” https://www.sciensano.be/fr/biblio/rapport-dactivites-sciensano-2020 (August 27, 2021).