30 October 2024 | Country Update

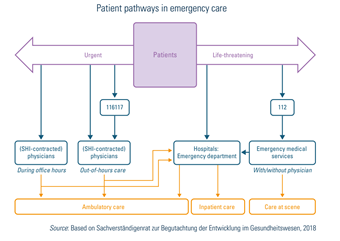

Establishment of Integrated Emergency Centres as part of an emergency care reformUrgent, out-of-hours and emergency care are provided via three main settings: ambulatory, inpatient and emergency medical services (EMS). Legally, the regulation and provision of emergency medical services are competences delegated to the states – and there are substantial variations with respect to how states organize and finance such services. The states are responsible for ensuring adequate EMS coverage across their territory and regulate most aspects of provision through their own “EMS law” (Rettungsdienstgesetz). Box5.5 and Fig5.4 describe patient pathways in emergency care.

| Box5.5 | Fig5.4 |

|  |

The Federal Ministry of Health is launching a new initiative to establish Integrated Emergency Centres (IECs) at selected hospitals across the country to provide more efficient and effective care for patients with acute conditions who cannot see their general practitioner. These IECs will comprise both an emergency room and an emergency practice.

At the IECs, a central reception desk will assess the most appropriate care for each patient. The emergency practice has a set opening hours schedule: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday from 18:00 to 21:00; Wednesday and Friday from 14:00 to 21:00; Saturday, Sunday, and national holidays from 9:00 to 21:00. Outside these hours, patients can receive care in the emergency room. The new regulations are set to take effect in early 2025, though some structures are still under development, with full services expected to be available by 2026.

The delivery of urgent and out-of-hours care is the responsibility of the respective Regional Association of SHI Physicians. Ambulatory physicians (SHI GPs and specialists) provide the major part of urgent care during regular practice hours or during out-of-hours services in their practice (and, if necessary, refer patients to other health care providers for subsequent treatment). Home visits are provided by the majority of GPs, but only by a few specialists.

Out-of-hours services are coordinated and organized by the Regional Associations of SHI Physicians as part of their obligation to guarantee service availability for ambulatory care (§75 (1) SGB V). In 2012 the nationwide telephone number 116117 was introduced, to coordinate patients and ensure they reach the most appropriate out-of-hours care service (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, 2020g). Except in cases of a life-threatening condition, telephone counselling, practice visits and home visits are provided by the respective physician in charge. Increasingly, out-of-hours services are also offered by ambulatory physicians at specific Regional Associations of SHI Physicians facilities, mostly at local hospitals (Portalpraxis), with the aim of improving access to care and avoiding unnecessary hospital visits.

Both SHI and PHI patients are entitled to publicly provided out-of-hours services. While the medical services provided by the physicians are regularly financed by the Regional Associations of SHI Physicians (see section 3.7.1 Paying for health services), the logistical costs for organization and technical implementation are financed by all GPs and specialists in ambulatory care in the respective region. Moreover, several private (for-profit) out-of-hours services provide physician care for PHI patients and/or patients paying out of pocket.

Life-threatening emergencies are treated by rescue and emergency medical services and include emergency rescue, emergency medical care and patient transport (including air, mountain, cave and water rescue). Emergency medical services are coordinated and monitored by about 250 centres across the country (called “rescue control centres” or “integrated control centres”), which can be reached via the Europe-wide emergency telephone number 112 (Fachverband Leitstellen e.V., 2014). The control centres differentiate between the need for rescue care and emergency physician care according to criteria listed in the “emergency doctor indication catalogue” (Notarztindikationskatalog). The predefined maximum time for EMS (Hilfsfrist) to reach people in need varies among states, ranging between 5 and 20 minutes after receiving the phone call (Schehadat et al., 2017). Emergency rescue care is usually regulated by states’ interior ministries and most states delegate organization and delivery to the counties. Within the framework of the EMS law, local communities may accredit, regulate and plan for capacities via integrated public providers (mostly integrated with fire protection) as well as through contracted private rescue providers.

Among private providers, priority is clearly given to non-profit providers over profit-making providers in legislation as well as in practice. Non-emergency transport is rarely performed by municipalities themselves but is outsourced to private non-profit or for-profit providers. The latter play a bigger role in this section of care than in other parts of the emergency care market, but welfare organizations still have priority in most states over private for-profit providers.

Significant differences can be found between urban and rural areas, as well as between states and municipalities regarding requirements for qualification and competences. EMS are mostly provided by the fire departments but are also increasingly provided by the four aid organizations (German Red Cross, Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe, Malteser Hilfsdienst and Arbeiter-Samariter Bund). These organizations are also commissioned with general emergency preparedness and response, and usually provide EMS during public events.

The two predominantly used vehicle types in Germany are ambulances (Rettungswagen – RTW) and emergency physicians’ vehicles (Notarzteinsatzfahrzeug – NEF). Ambulance crews normally consist of two qualified crew members. Teams in emergency physicians’ vehicles usually consist of one physician, often with special training and a qualification as an “EMS physician”, and one paramedic. Physicians can attend special training to qualify as an EMS physician. The role of paramedics in rescue care in Germany includes multiple qualifications, such as “emergency paramedics” (Notfallsanitäter – NFS), “rescue assistants” (Rettungsassistent) and “rescue paramedics” (Rettungssanitäter). After the implementation of the emergency paramedics qualification with the Emergency Paramedics Act, 2013 (Gesetz über den Beruf der Notfallsanitäterin und des Notfallsanitäters), the training of rescue assistants was discontinued. Control centres primarily send ambulances and emergency physicians’ vehicles, but dispatch of the fire department, police, first responders, rescue helicopters and special vehicles (such as STEMO-vehicles for thrombolysis) is also possible according to availability. Special vehicles can vary between urban and rural regions or states and municipalities, but rescue via ambulance or emergency rescue helicopters is available throughout Germany.

Financing rescue care follows a dual principle: while recurrent expenditure is financed by SHI or PHI or out of pocket, capital financing is mainly a task for the states. For hospital-based emergency care, the dual principle also applies, albeit according to the general rules of hospital financing and planning (see section 3.7.1 Paying for health services). With respect to capital financing, there are variations among the states (see also Busse & Blümel, 2014; Busse et al., 2017b). Patient “transport” (§60 SGB V) is based on a reimbursement system with a retrospective fee-for-service. Co-payments account for 10% (minimum of €5, maximum of €10) and apply for non-emergency and emergency transport services (see section 3.4 Out-of-pocket payments). In addition, non-rescue patient transport has been excluded from SHI. A few exceptions have been outlined by the Federal Joint Committee, including the transport of patients in need of challenging ambulatory treatments such as chemotherapy and haemodialysis (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, (2020a).

Emergency care in Germany is strongly characterized by sectoral segregation. The EMS, the emergency departments of hospitals and the rescue services work often in parallel and are not well connected. According to the obligation to guarantee service availability, urgent ambulatory care should be provided 24/7 by physicians. However, patients often make use of the emergency departments of hospitals or the EMS, even though from a medical point of view they could be provided with ambulatory care. One reason for this is that responsibilities among the various providers are not clear. Another is that patients seem to have expectations to access better and faster care. Hence, the patient’s pathway depends primarily on the patient’s own assessments, expectations and wishes.

Most recently, urgent and emergency care has been identified as needing reform (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), 2020c). Reform plans included the Reform of the Emergency Care Act. The legislation’s aim was to promote joint emergency management systems via the telephone number 112 or 116117 and to establish integrated emergency centres (Integriertes Notfallzentrum – INZ) in selected hospitals to differentiate whether patients should be treated in inpatient or ambulatory facilities. The reform has been postponed due to the more immediate challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG), 2020l, 2020m).