Allocative efficiency indicates the extent to which limited funds are directed towards purchasing an appropriate mix of health services or interventions that maximize health improvements.

In 2016, 65.6% of current spending on health was directed to curative inpatient and outpatient care. This is high when compared with other EU countries, where curative care accounts for just under 60% of spending (Fig7.4). The share spent on inpatient curative care (35.5%) has remained high despite the efforts to shift service provision to outpatient care (for example, for small surgical procedures) through modifications of payment mechanisms for specialist outpatient care (see section 3.7.1). On the other hand, expenditure on prevention and public health account for only 2.7% of total current health expenditure.

Fig7.4

Decisions on the reimbursement of medicines are informed by non-binding recommendations by the HTA agency (AOTMiT) and it is preceded by clinical effectiveness, cost–effectiveness and budget impact analyses. AOTMiT also conducts appraisals of health services and publicly financed health policy programmes and, overall, the role of HTA is very important in Poland compared with other central and eastern European countries but also compared with many countries in western Europe. Negative opinions of AOTMiT effectively block territorial self-government units from implementation of their planned health policy programmes and conditionally positive opinions require appropriate adjustments of these programmes before they are implemented (see section 2.4.3).

Health policy priorities are established based on the maps of health needs (see section 2.4). Centrally pooled resources are divided among the voivodeship branches of the NFZ according to a formula that takes into account the demographic characteristics of the voivodeships (number, gender and age structure of the insured persons) and the amount granted in the previous year. Although this formula has been changed over the years in an attempt to reduce disparities among the voivodeships, it does not eliminate the variation in per capita spending across the branches and allocation of resources remains skewed in favour of the richer regions (see section 3.3.3).

Despite certain positive trends, efficient utilization of available resources still faces numerous obstacles. The average length of stay (ALOS) for acute care for all causes is comparable to the EU average: 6.6 days in 2014 in Poland and 6.4 days in the EU28 and its value has decreased in the last decade (from 7.9 days in 2005). The value of the same indicator for all hospitals (not only acute) was 6.9 days for Poland and 8.2 for the EU (the value of this indicator in Poland decreased from 8.2 in 2005) (WHO, 2018a). There are variations in ALOS value for different types of care. For example, in 2015, ALOS for acute myocardial infraction was shorter in Poland compared with the OECD average but it was longer for single spontaneous delivery (OECD, 2018b).

In terms of the average beds occupancy ratio, its value is relatively low in Poland and has been decreasing. According to the Ministry of Health data, the average occupancy beds ratio for general hospitals dropped from 68.1% in 2010 to 65.8% in 2017 (CSIOZ, 2011, 2018b), although it varies for different types of wards (Table7.6). In comparison, the average occupancy ratio for beds in acute hospitals in the EU was stable at 77% between 2010 and 2014 (WHO, 2018a). This relatively low bed occupancy ratio in Poland can be explained by excess hospital infrastructure. Fragmentation of hospital ownership and lack of strong stewardship at the central level have resulted in poor planning of infrastructure and equipment investments; for example, with similar equipment being bought by neighbouring hospitals (NIK, 2013b; MZ, 2015). The introduction of a system for assessing investments in health care in 2016 (IOWISZ) is hoped to improve the allocation of resources in the system (see section 4.1).

Table7.6

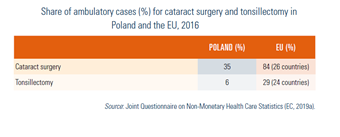

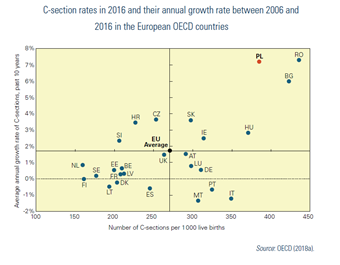

Day care is not well developed in Poland, compared with the United Kingdom, the Nordic countries and countries in the west of Europe (Table7.7). On the other hand, the C-section rate[26] is very high and growing fast (Fig7.5).

| Table7.7 | Fig7.5 |

|  |

Excess capacity in the hospital sector is accompanied by deficits in the provision of outpatient care. Waiting times for specialist consultations are very long and Poland has comparatively high hospitalization rates for chronic conditions (e.g. asthma and COPD) that can be managed in the outpatient sector (see section 7.6). Cooperation between primary, secondary and tertiary care levels is low, partly due to the low level of IT use and incompatibility of the IT systems (see section 4.1). However, efforts have been made to improve coordination of care (see Box5.2).

Box5.2

The numbers of doctors and nurses per 100 000 population in Poland are some of the lowest in the EU (see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018). However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to USEU (see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018). However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to US$ 369 compared with US$ 378 in Estonia, US$ 433 in Czechia, US$ 452 in Latvia, US$ 541 in Lithuania, and US$ 566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

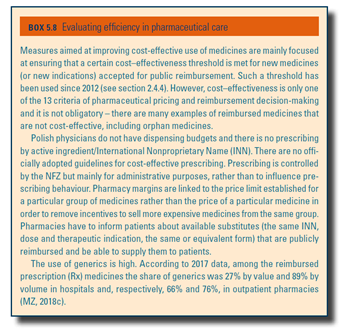

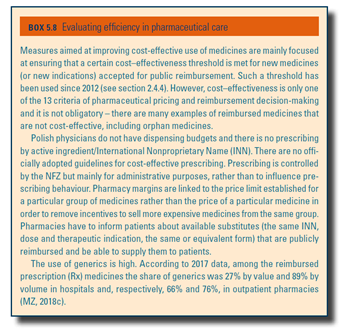

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

nbsp;369 compared with USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

nbsp;369 compared with USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to US$ 369 compared with US$ 378 in Estonia, US$ 433 in Czechia, US$ 452 in Latvia, US$ 541 in Lithuania, and US$ 566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

nbsp;378 in Estonia, USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

nbsp;378 in Estonia, USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to US$ 369 compared with US$ 378 in Estonia, US$ 433 in Czechia, US$ 452 in Latvia, US$ 541 in Lithuania, and US$ 566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

nbsp;433 in Czechia, USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

nbsp;433 in Czechia, USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to US$ 369 compared with US$ 378 in Estonia, US$ 433 in Czechia, US$ 452 in Latvia, US$ 541 in Lithuania, and US$ 566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

nbsp;452 in Latvia, USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

nbsp;452 in Latvia, USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to US$ 369 compared with US$ 378 in Estonia, US$ 433 in Czechia, US$ 452 in Latvia, US$ 541 in Lithuania, and US$ 566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

nbsp;541 in Lithuania, and USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

nbsp;541 in Lithuania, and USEU

(see section 4.2.) and despite some ad hoc actions taken by the

government to alleviate the problem, such as shortening the duration of

residency training for doctors, they remain low. In 2017, the Ministry

of Health proposed to allow doctors to work across different wards in

the same hospital (MZ, 2017b) and in 2018, the Ministry proposed to

introduce a new profession of “medical secretary” to alleviate the

administrative burden of physicians (MZ, KL/Rynek Zdrowia, 2018).

However, strategic human resources planning is lacking and deficits in

the numbers of doctors and nurses are likely to persist.

In 2017, per capita spending on outpatient pharmaceuticals in Poland amounted to US$ 369 compared with US$ 378 in Estonia, US$ 433 in Czechia, US$ 452 in Latvia, US$ 541 in Lithuania, and US$ 566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

nbsp;566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD

countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on

medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values

and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

nbsp;566 in Slovakia and Hungary (fifth lowest among 35 OECD countries for which there were data; OECD, 2018c). In terms of the share of GDP spent on pharmaceuticals, Poland was placed 18th among the 35 OECD

countries for which there were data. While per capita spending on

medicines is relatively low in Poland, both in terms of absolute values

and as a share of GDP, Poland ranked ninth highest among OECD countries in terms of the share of current health expenditure spent on pharmaceuticals (20.7%) (OECD, 2018c). High expenditure on medicines presents a significant financial burden to households and the share of OOP spending on health that goes on purchasing medicines (approximately 60%) is the second highest (after Mexico) among 31 OECD countries for which such data were available (OECD, 2017).

The market of generic medicines is well developed. Market shares of generic medicines are among the highest in Europe – close to 70% by volume and over 40% by value, according to 2014 data (Albrecht et al., 2015). However, before 2012, price competition in the market of generics was considered to be insufficient and this resulted in the passing of the Act on the Reimbursement of Pharmaceuticals, Foodstuffs for Special Nutritional Use and Medical Devices in 2012. According to this Act, the MAH who is the first to apply for the reimbursement of a generic drug must set its price at 25% below the price of the original drug on the reimbursement list. For all subsequent applications, prices of generics cannot exceed the current reimbursement limit (see section 2.4). These new rules have promoted price competition and lowered price differentials between generics and among equivalent branded medicines. However, since they only apply to medicines that have entered the market since 2012, some high price differences that existed before 2012 persist.

Medicines are still prescribed with their trade names and prescribing by International Nonproprietary Names (INN) is not obligatory (see Box5.8). Nevertheless, pharmacists are legally obliged (by the 2012 Act, see above) to inform patients about the possibility of purchasing a cheaper generic equivalent and to hold such products in stock.

Box5.8

Substandard and counterfeit medicines do not seem to represent a major problem in Poland. However, Poland has been assessed as being only partially compliant with the Falsified Medicines Directive of the European Union (Directive 2011/62/EU) which is to be implemented by February 2019 (Merks et al., 2018).